Results for “baumol” 55 found

Overcoming Baumol

One way to overcome the Baumol effect is to replace labor with capital. AI and robots are making that possible. Here’s a clip of the Carmelite Monks of Wyoming who are building a monastery in the Gothic style using CNC machines:

CNC machines and robots have unlocked the ability to relatively quickly carve the intense details of a Gothic church. Ornate pieces that used to take months for a skilled carver, now can be accomplished in a matter of days. Instead of cutting out the beauty, using the excuse that it takes too long, thus doesn’t fit into the budget, modern technology can be used to make true Gothic in all its beauty a reality again today.

Bring back the beauty!

Special Features of the Baumol Effect

I explained the Baumol effect in an earlier post based on Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?. In this post, I want to point out some special features of the Baumol effect that help to explain the data. Namely:

- The Baumol effect predicts that more spending will be accompanied by no increase in quality.

- The Baumol effect predicts that the increase in the relative price of the low productivity sector will be fastest when the economy is booming. i.e. the cost “disease” will be at its worst when the economy is most healthy!

- The Baumol effect cleanly resolves the mystery of higher prices accompanied by higher quantity demanded.

First, in the literature on rising prices it’s common to contrast massive increases in spending with little to no increases in quality, as for example, in contrasting education expenditures with mostly flat test scores (see at right). We have spent so much and gotten so little! Cui Bono? It must be teacher unions, administrators or the government!

All of that could be true but the Baumol effect predicts that more spending will be accompanied by no increase in quality. Go back to the classic example of the string quartet which becomes more expensive because labor in other industries increases in productivity over time. The price of the string quartet rises but does anyone expect that the the quality rises? Of course not. In the classic example the inputs to string quartet playing don’t change. The wages of the players rise because of productivity increases in other industries but we don’t invest any more real resources in string quartet playing and so we should not expect any increases in quality.

In just the same way, to the extent that greater spending on education, health care, or car repair is due to the rising opportunity costs of inputs we should not expect any increase in quality. (Note that increases in real resource use such as more teachers per student should result in increases in quality (and perhaps they do) but by eliminating the price increase portion of the higher spending we have eliminated a large portion of the mystery of higher spending with no increase in quality.)

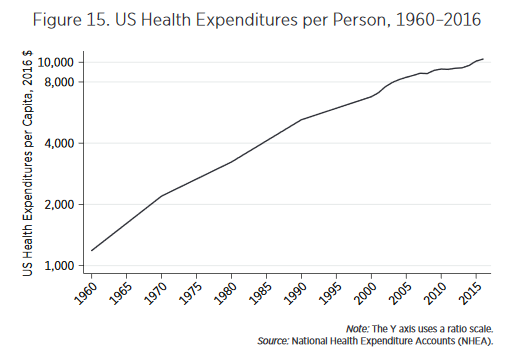

Second, explanations of rising prices that focus on bad things such as monopoly power or rent seeking tend to imply that price increases should be largest when the economy is doing poorly. In contrast, the Baumol effect predicts that increases in relative prices will be largest when the economy is booming. Consider health care. From news reports you might think that health care costs have gotten more “out of control” over time. In fact, the fastest increases in health care costs were in the 1960s. The graph at left is on a ratio scale so slopes indicate rates of growth and what one sees is that the growth rate of health expenditures per person is slowing. That might seem good but remember, from the Baumol point of view, the decline in relative price growth reflects slowing growth elsewhere in the economy.

Second, explanations of rising prices that focus on bad things such as monopoly power or rent seeking tend to imply that price increases should be largest when the economy is doing poorly. In contrast, the Baumol effect predicts that increases in relative prices will be largest when the economy is booming. Consider health care. From news reports you might think that health care costs have gotten more “out of control” over time. In fact, the fastest increases in health care costs were in the 1960s. The graph at left is on a ratio scale so slopes indicate rates of growth and what one sees is that the growth rate of health expenditures per person is slowing. That might seem good but remember, from the Baumol point of view, the decline in relative price growth reflects slowing growth elsewhere in the economy.

Third, holding all else equal, the only rational response to an ordinary cost increase is to substitute away from the good. But in many rising price sectors we see not only greater expenditures (driven by increased prices and inelastic demand) but also greater quantity demanded. As I showed earlier, for example, we have increased the number of doctors, nurses and teachers per capita even as prices have risen. John Cochrane correctly noted that this is puzzling but it’s a bigger puzzle for non-Baumol theories than for Baumol. For non-Baumol theories to explain increases in the quantity purchased, we need two theories. One theory to explain the increase in price (bloat/regulation etc.) and another theory to explain why, despite the increase in price, people are still purchasing more (e.g. income effect). The world is a messy place and maybe that is what is happening. But the Baumol effect offers a cleaner answer.

A Baumol increase in relative price is always accompanied by higher income so it’s much easier to explain how price increases can accompany increases in quantity as well as increases in expenditure. The Baumol story for increased purchase of medical care even as prices increase, for example, is no more mysterious than why people can take more leisure when wages increase–namely the higher wage means a higher income for any given hours and people choose to take some of this higher income in leisure. Similarly, higher productivity in say goods production increases income at any given production level and people choose to take some of this higher income in services.

Summing up, if we examine each sector–education, health care, the arts, etc.–on its own then there are always many possible explanations for why prices might be increasing. Many of these explanations have true premises–there are a lot of administrators in higher education, health care is highly regulated, lower education is government run. But, on closer inspection the arguments often don’t fit the data very well. Prices were increasing before administrators were important, health care is highly regulated but so is manufacturing, private education is also increasing in price, the arts are not highly regulated. It’s impossible to knock down each of these arguments in every industry, so there is always room for doubt. Indeed, the great difficult is that these factors often do result in higher costs and greater inefficiency but I believe those are predominantly level effects not effects that accumulate over time. Moreover, when one considers the rising price industries as a whole these explanations begin to look ad hoc. In contrast, the Baumol effect appears capable of explaining the pricing behavior of a wide variety of industries over a long period of time using a simple but powerful and unified theory.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

The Baumol Effect

After looking at education and health care and doing a statistical analysis covering 139 industries, Helland and I conclude that a big factor in price increases over time in the rising price of skilled labor. Many industries use skilled labor, however, and even so prices decline so that cannot be a full explanation. Moreover, why is the price of skilled labor increasing? The Baumol effect answers both of these questions. In this post, I’ll explain the effect drawing from Why Are the Prices so D*mn High.

The Baumol effect is easy to explain but difficult to grasp. In 1826, when Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 was first played, it took four people 40 minutes to produce a performance. In 2010, it still took four people 40 minutes to produce a performance. Stated differently, in the nearly 200 years between 1826 and 2010, there was no growth in string quartet labor productivity. In 1826 it took 2.66 labor hours to produce one unit of output, and it took 2.66 labor hours to produce one unit of output in 2010.

Fortunately, most other sectors of the economy have experienced substantial growth in labor productivity since 1826. We can measure growth in labor productivity in the economy as a whole by looking at the growth in real wages. In 1826 the average hourly wage for a production worker was $1.14. In 2010 the average hourly wage for a production worker was $26.44, approximately 23 times higher in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Growth in average labor productivity has a surprising implication: it makes the output of slow productivity-growth sectors (relatively) more expensive. In 1826, the average wage of $1.14 meant that the 2.66 hours needed to produce a performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 had an opportunity cost of just $3.02. At a wage of $26.44, the 2.66 hours of labor in music production had an opportunity cost of $70.33. Thus, in 2010 it was 23 times (70.33/3.02) more expensive to produce a performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 than in 1826. In other words, one had to give up more other goods and services to produce a music performance in 2010 than one did in 1826. Why? Simply because in 2010, society was better at producing other goods and services than in 1826.

The 23 times increase in the relative price of the string quartet is the driving force of Baumol’s cost disease. The focus on relative prices tells us that the cost disease is misnamed. The cost disease is not a disease but a blessing. To be sure, it would be better if productivity increased in all industries, but that is just to say that more is better. There is nothing negative about productivity growth, even if it is unbalanced.

In this post, I will discuss some implications of the fact that productivity is unbalanced. See the book for more discussion and speculation about why productivity growth is systematically unbalanced.

The Baumol effect reminds us that all prices are relative prices. An implication is that over time prices have very little connection to affordability. If the price of the same can of soup is higher at Wegmans than at Walmart we understand that soup is more affordable at Walmart. But if the price of the same can of soup is higher today than in the past it doesn’t imply that soup was more affordable in the past, even if we have done all the right corrections for inflation.

We can see this in the diagram at right. We have a two-good economy, Cars and Education. The production possibilities frontier shows all the combinations of Cars and Education that we can afford given our technology and resources at time 1 (PPF 1). Now suppose society chooses to consume the bundle of goods denoted by point (a). The relative price of Cars and Education is given by the slope of the PPF at that point. That price/slope tells us if we give up some education how many more cars can we get? In a market economy the price has to be given by the slope of the PPF because that is the only price at which people will willing consume the bundle of goods at point (a), i.e. it’s the equilibrium price.

Now at time 2, productivity has increased which means that with the same resources we can now have more of both goods. Productivity of Car production has increased more than that of Education production, however, so the curve shifts out more towards Cars than towards Education. Suppose society continues to consume Cars and Education in the same proportions, i.e. at point (b). The price of education must increase–and all that means is that if we give up a unit of education at point b we will get more cars than before which is the same as saying that if we want more education at point b we must give up more cars than before, i.e. the price has increased.

Notice, however, that although the price of education has increased, education is not less affordable. Indeed, at point (b) we are consuming more of both goods–broadly speaking this is exactly what has happened–namely, the price of education has increased and we now consume more of it than ever before.

When we recognize that all prices are relative prices the following simple yet deep facts follow:

- If productivity increases in some industries more than others then, ceteris paribus, some prices must increase.

- Over time, all real prices cannot fall.

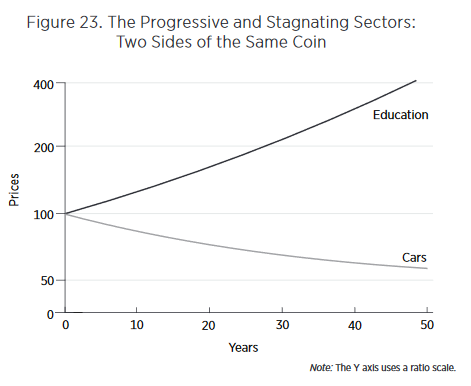

In Figure 22 the economy moves from point (a) to point (b). If we graph the same transition over time it will look something like Figure 23.

Looking at such graphs, our attention naturally is drawn to the rising cost of education. Why are costs rising so quickly? Entranced by such graphs, we may enter into a detailed analysis of the special factors of education—regulation, unionization, government purchases, insurance, international trade, and so forth—to try to explain the dramatic increase in costs. Yet the rising costs in the education sector are simply a reflection of increased productivity in the car sector. Thus, another deep lesson of the Baumol effect is that to understand why costs in the stagnant sector are rising, we must look away from the stagnating sector and toward the progressive sector.

Finally, there is one other addition to the Baumol effect which is not often recognized but worth drawing attention to. In Figure 22, I assumed that preferences were such that people wanted to consume the same ratio of goods over time so we moved from point (a) to point (b). But suppose that as we get wealthier we get tired of more cars and would like relatively more education so we move towards point (d). As we move from point (b) to point (d) we are taking resources away from car production, resources which were probably well-suited to making cars, and instead moving them towards education where they are probably less well suited. As a result as we move from point (b) to point (d) we are driving up the price of education as we try to turn auto workers into teachers. In this case, the Baumol effect gets magnified. We could alternatively move from point (b) to point (c) which would turn teachers into less productive auto workers thus driving down the price of education (i.e. increasing the price of cars). Thus, depending on preferences, the Baumol effect can be magnified or ameliorated.

As a society it appears that with greater wealth we have wanted to consume more of the goods like education and health care that have relatively slow productivity growth. Thus, preferences have magnified the Baumol effect.

Next week, I will wrap up the discussion by explaining some features of the data that the Baumol effect fits much better than do other theories.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

William Baumol has passed away

He was one of the greatest of living economists, with contributions in numerous areas, including productivity, economics of the arts, contestable markets, environmental economics, and entrepreneurship theory. Here are previous MR entries on Baumol and his ideas.

Measuring Baumol and Bowen Effects in Public Research Universities

That is a new paper by Robert E. Martin and R. Carter Hill:

We estimate three models of cost per student using data from Carnegie I and II public research universities. There are 841 usable observations covering the period from 1987 to 2008. We find that staffing ratios are individually and collectively significant in each model. Further, we find evidence that shared governance lowers cost and that the optimal staffing ratio is approximately three tenure track faculty members for every one full time administrator. Costs are higher if the ratio is higher or lower than three to one. As of 2008 the number of full time administrators is almost double the number of tenure track faculty. Using the differential method and the coefficients estimated in the three models, we deconstruct the real cost changes per student between 1987 and 2008 into Baumol and Bowen effects. This analysis reveals that for every $1 in Baumol cost effects there are over $2 in Bowen cost effects. Taken together, these results suggest two thirds of the real cost changes between 1987 and 2008 are due to weak shared governance and serious agency problems among administrators and boards.

For the pointer I thank Michael Tamada (who does not necessarily endorse the argument).

Baumol’s new book on the cost disease

It is self-recommending, here are a few points of relevance:

1. There has been a clear cost disease in most kinds of education and many kinds of medicine, but I blame institutions and laws as much as the intrinsic nature of the product.

2. I do not see the arts as subject to the cost disease very much at all. As for the “live performing arts,” the disease seems to afflict the older and less innovative sectors, such as opera and the symphony. There is plenty of live music these days, it is offered in innovative ways, and much of it is free.

3. Even “the live performing arts” can be broken down into underlying characteristics, many of which show a great deal of recent innovation. For instance the supply of “musical immediacy” has been non-stagnant through YouTube, which often gives you a better glimpse of the performer than you get through nosebleed seats and giant screens. YouTube isn’t “live,” but there is no particular reason to break down the analysis at that level and certainly it is not a sacred category for consumers.

4. In many sectors of the arts, especially music, consumers demand constant turnover of product. Old music becomes “obsolete” — for whatever sociological reasons — and in this sense the sector is creating lots of new value every year. From an “objectivist” point of view they are still strumming guitars with the same speed, but from a subjectivist point of view — the relevant one for the economist – they are remarkably innovative all the time in the battle against obsolescence. A lot of the cost disease argument is actually an aesthetic objection that the art forms which have already peaked — such as Mozart — sometimes have a hard time holding their ground in terms of cost and innovation.

5. In general “cost disease” sectors do not remain constant over time. Agriculture has been unusually stagnant for the last twenty or so years, but it is hardly obvious that this trend will continue for the next century to come and it certainly was not the case for the period 1948-1990, quite the contrary.

6. The stagnancy of one sector may depend on the stagnancy of other sectors in non-transparent ways. “Live music” may seem like it doesn’t change much, but lifting the embargo on Cuba would boost the quantity and quality of my consumption of spectacular concert experiences, as would a non-stop flight to Haiti.

You can buy the book here.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments.

The Productivity of Online Education Increases

Teaching is a labor-intensive service industry for which it is difficult to increase productivity. Thus, the price of education rises over time, the Baumol effect. One of the reasons Tyler and I have put a lot of effort into online education is that it ties education to high productivity growth industries such as software and technology. Thus in the Industrial Organization of Online Education we argued:

…as more of the value of a course comes from software and less from live teaching, productivity will improve, thus removing the cost disease.

Here’s a case in point:

This is just a test but all of the videos for our textbook, Modern Principles, and our free online platform Marginal Revolution University are already subtitled in many languages and soon we will see more translations like the one above. Amazing.

The Harried Leisure Class

How easy is it for a male breadwinner to raise a family? Oren Cass argues that the cost of “thriving,” is increasing. That’s false. When you do the numbers correctly, Winship and Horpedahl show that the cost of thriving is falling. It’s falling more slowly than we would like–but it’s still the case that current generations are, on the whole, better off than previous generations.

Still, Winship and Horpedahl face an upward battle because while they are right on the numbers many people feel that they are wrong. Almost every generation harbors a nostalgic belief that circumstances were more favorable during their youth. Moreover, even though people are better off today, social media may have magnified invidious comparisons so everyone feels they are worse off than someone else.

I offer a third reason: the Linder Theorem. Real GDP per capita has doubled since the early 1980s but there are still only 24 hours in a day. How do consumers respond to all that increased wealth and no additional time? By focusing consumption on goods that are cheap to consume in time. We consume “fast food,” we choose to watch television or movies “on demand,” rather than read books or go to plays or live music performances. We consume multiple goods at the same time as when we eat and watch, talk and drive, and exercise and listen. And we manage, schedule and control our time more carefully with time planners, “to do” lists and calendaring. A search at Amazon for “time management,” for example, leads to over 10,000 hits.

Time management is a cognitively strenuous task, leaving us feeling harried. As the opportunity cost of time increases, our concern about “wasting” our precious hours grows more acute. On balance, we are better off, but the blessing of high-value time can overwhelm some individuals, just as can the ready availability of high-calorie food.

So, whose time has seen an especially remarkable appreciation in the past few decades? Women’s time has experienced a surge in value. As more women have pursued higher education and stepped into professional roles, their time’s value has more than doubled, incentivizing a substantial reorganization of daily life with consequent transaction costs.

It’s expensive for highly educated women to be homemakers but that means substituting the wife’s time for a host of market services, day care, house cleaning, transportation and so forth. Juggling all of these tasks is difficult. Women’s time has become more valuable but also more constrained and requiring more strategic allocation and optimization for both spouses. In previous eras, a spouse who stayed at home served as a reserve pool of time, providing a buffer to manage unexpected disruptions such as a sick child or a car breakdown with greater ease. Today, the same disruption require a cascade of rescheduling and negotiations to manage the situation effectively. It feels hard.

By the way, the same theory also explains why life often appears to unfold at a slower, more serene pace in developing nations. It’s not just an illusion of being on holiday. In places where time is less economically valuable, meals stretch more leisurely, conversations delve deeper, and time itself seems to trudge rather than race. In contrast, with economic development comes an increased pace of life–characterized by a proliferation of fast food, accelerated conversation, and even brisker walking (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999).

Linder’s theorem, as you may have correctly surmised, is related to Baumol’s theorem. In fact, Baumol (1973, p. 630) explained Linder’s theorem succinctly, “rising productivity decreases the demand for commodities whose consumption is expensive in time.” In essence, Baumol’s theorem is about the cost of production while Linder’s theorem is about the cost of consumption. I discuss Baumol and Linder at greater length here (ungated).

If the value of time fell, we might find ourselves eating more leisurely meals and taking more time to appreciate the simple pleasures in life. But, contrary to popular belief, neither Baumol nor Linder effects reduce our well-being; instead, they are a byproduct of economic growth and greater wealth. Rather than lamenting the rise in relative prices, we should recognize and appreciate our ability to afford them, and even acknowledge that on certain occasions, they are worth paying.

Tabarrok on Stranded Technologies Podcast

I talk with entreprenreur Niklas Anzinger on the Stranded Technlogies Podcast. Niklas summarizes some of the discussion:

- This episode is an intellectual journey that discovers insights that can be used by entrepreneurs and city developers. We talk about the Baumol effect that Alex uses to explain the now infamous price chart.

- Alex’s recommendation to new city or governance startups like Prospera, Ciudad Morazan or the Catawba DEZ is to think of city development as a “dance between centralization and decentralization”.

- Economists have developed concepts that are waiting to be commercialized, e.g. prediction markets. In this episode, we talk about dominant assurance contracts and how they could be used in new city developments and fundraising.

OTC Prescriptions Save on Medical Costs

The excellent Joel Selanikio writes on medical disruption from the rise of self-care:

I’ve been asked many times whether I think that AI will replace doctors. Never once have I been asked if I thought that OTC drugs could replace doctors. But that’s exactly what they have done: every time a drug switches from prescription to OTC, the total number of doctor visits drops.

In fact, a 2012 study by Booz concluded that

“if OTC medicines did not exist, an additional 56,000 medical practitioners would need to work full-time to accommodate the increase in office visits by consumers seeking prescriptions for self-treatable conditions.”

Fifty-six thousand doctors that we don’t need because of OTC drugs; that’s almost 6% of the practicing doctors in America. Think of the effect on healthcare costs.

Selanikio gives more examples of how AI plus super-computers, i.e. cell phones, can lead to better, at-home diagnosis and fewer physician hours (and more here). More generally, due to the Baumol effect the only way to save on medical care costs is by using less labor and more capital–this is rarely recognized.

Monday assorted links

1. An alternative to the Baumol cost-disease hypothesis (but is it really, isn’t worker allocation across sectors endogenous to, among other things, Baumol-like factors?)

3. Please stop saying that hot drinks cool you down.

4. “…mass shootings are more likely after anniversaries of the most deadly historical mass shootings. Taken together, these results lend support to a behavioral contagion mechanism following the public salience of mass shootings.” Link here.

5. What motivates leaders to invest in nation-building?

Buy Things Not Experiences!

![]()

A nice, well-reasoned piece from Harold Lee pushing back on the idea that we should buy experiences not goods:

While I appreciate the Stoic-style appraisal of what really brings happiness, economically, this analysis seems precisely backward. It amounts to saying that in an age of industrialization and globalism, when material goods are cheaper than ever, we should avoid partaking of this abundance. Instead, we should consume services afflicted by Baumol’s cost disease, taking long vacations and getting expensive haircuts which are just as hard to produce as ever.

Put that way, the focus on minimalism sounds like a new form of conspicuous consumption. Now that even the poor can afford material goods, let’s denigrate goods while highlighting the remaining luxuries that only the affluent can enjoy and show off to their friends.

[The distinction is too tightly drawn]…tools and possessions enable new experiences. A well-appointed kitchen allows you to cook healthy meals for yourself rather than ordering delivery night after night. A toolbox lets you fix things around the house and in the process learn to appreciate how our modern world was made. A spacious living room makes it easy for your friends to come over and catch up on one another’s lives. A hunting rifle can produce not only meat, but also camaraderie and a sense of connection with the natural world of our forefathers. In truth, there is no real boundary between things and experiences. There are experience-like things; like a basement carpentry workshop or a fine collection of loose-leaf tea. And there are thing-like experiences, like an Instagrammable vacation that collects a bunch of likes but soon fades from memory.

Indeed, much of what is wrong with our modern lifestyles is, in a sense, a matter of overconsuming experiences. The sectors of the economy that are becoming more expensive every year – which are preventing people from building durable wealth – include real estate and education, both items that are sold by the promise of irreplaceable “experiences.” Healthcare, too, is a modern experience that is best avoided. As a percent of GDP, these are the growing expenditures that are eating up people’s wallets, not durable goods. If we really want to live a minimalist life, then forget about throwing away boxes of stuff, and focus on downsizing education, real estate, and healthcare.

Hat tip: The Browser.

Photo Credit: MaxPixel.

Sunday assorted links

1. A problem in Baumol’s cost-disease argument.

2. Further fluvoxamine coverage. With a dose of Canadian nationalism. And Andy Slavitt agrees with the Israelis.

3. The culture that is Tlaxcalan the Tlaxcalan view of the Conquest and Cortes.

4. Soros on Xi (WSJ).

5. Did you expect the Spanish Inquisition (to have long-run, persistent effects)?

Self Recommending Links

1. I had a fun and wide-ranging conversation with Jonah Goldberg on the Remnant. We covered the economy, immigration, cyborgs and the Baumol effect among other topics.

2. Tim Harford covers fractional dosing at the FT:

The concept of a standard or full dose is fuzzier than one might imagine. These vaccines were developed at great speed, with a focus on effectiveness that meant erring towards high doses. Melissa Moore, a chief scientific officer at Moderna, has acknowledged this. It is plausible that we will come to regard the current doses as needlessly high.

3. The Brunswick Group interviews me:

Act like you’re in a crisis. That has been economist Alex Tabarrok’s advice since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tabarrok was among the earliest and loudest voices arguing for urgency and risk-taking when it came to increasing rapid testing, investing in vaccine capacity, and employing flexible vaccine dosing. In hindsight, he has been proven regularly right when most health experts were wrong.

Random Critical Analysis on Health Care

The excellent Random Critical Analysis has a long blog post, really a short book, on why the conventional wisdom about health care, especially in the United States, is wrong. It’s a tour-de-force. Difficult to summarize but, as I see it, the key points are the following. (I also drawn on It’s still not the health care prices.)

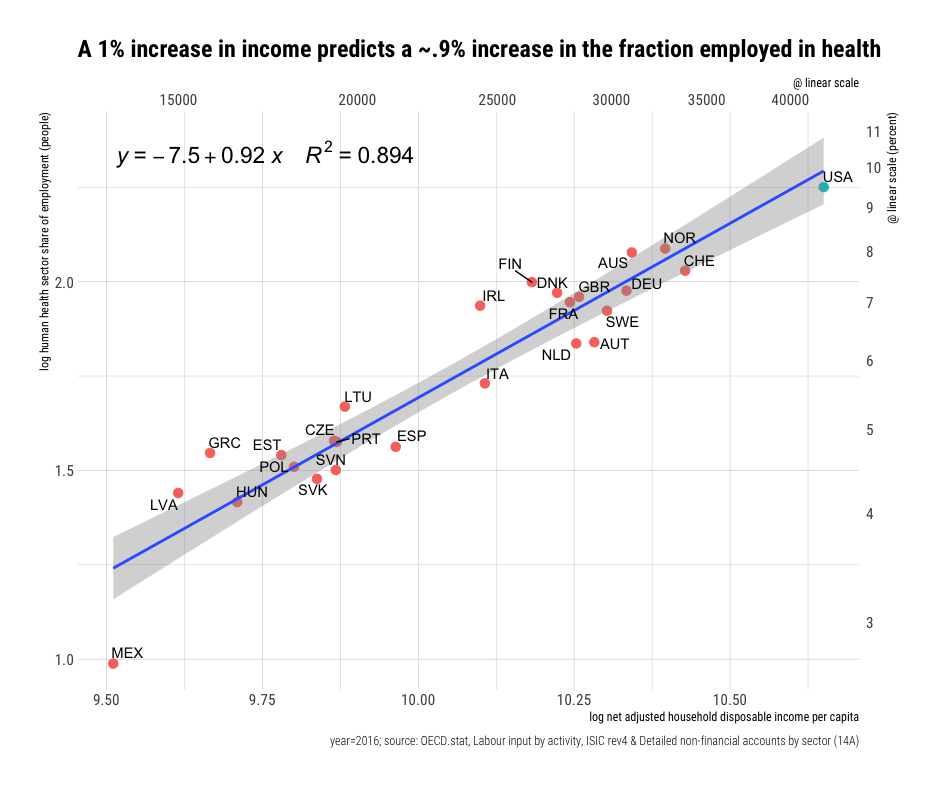

1. Health care spending is well predicted, indeed caused, by income.

Notice that the United States doesn’t look unusual when income is measured at the household level, i.e. Actual Individual Consumption, which measures the value of the bundle consumed by households whether the bundle items are bought in the market or provided by governments or non-profits. (AIC also avoids some issues with GDP per capita when a country has lots of intellectual property and exports, e.g. Ireland).

Notice that the United States doesn’t look unusual when income is measured at the household level, i.e. Actual Individual Consumption, which measures the value of the bundle consumed by households whether the bundle items are bought in the market or provided by governments or non-profits. (AIC also avoids some issues with GDP per capita when a country has lots of intellectual property and exports, e.g. Ireland).

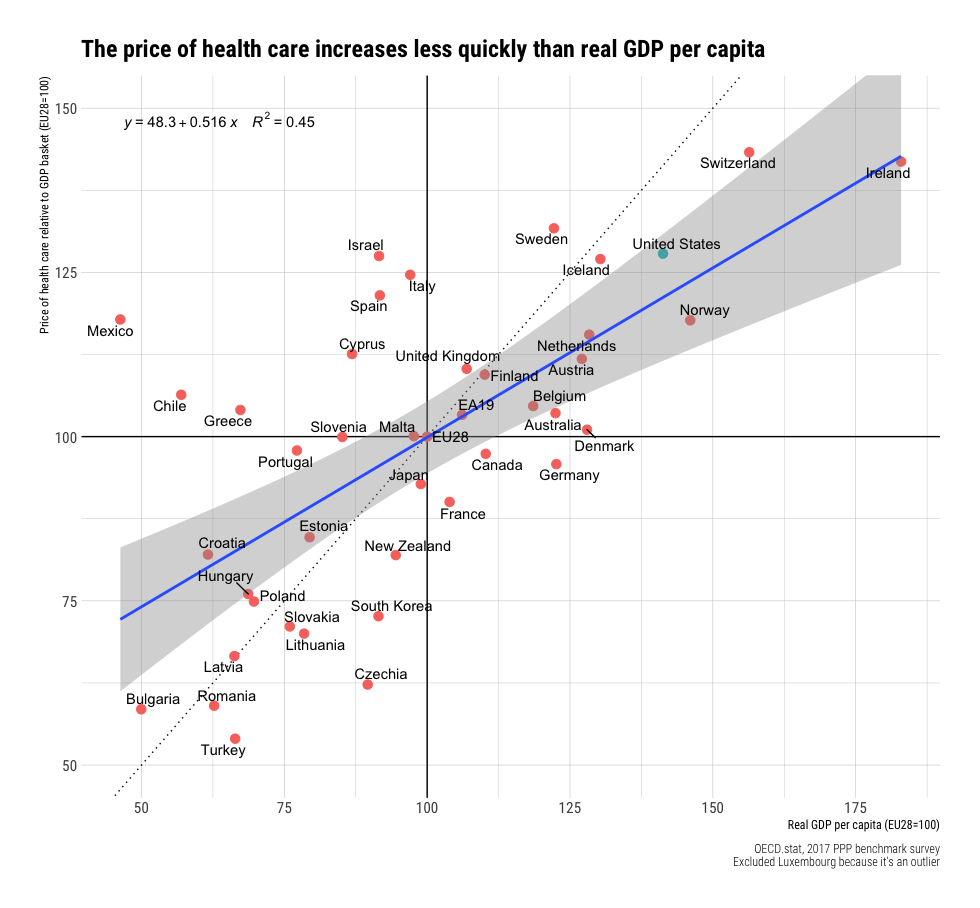

2. The price of health care increases with income but at a slower rate than income.

As a result of the above:

3. The price of health care relative to income is lower in rich countries, including the United States.

Let that sink in, health care prices are lower relative to income in richer countries. Health care in the United States is cheaper relative to income than in Greece, for example.

Since spending is going up faster than income but prices are not it must be the case that quantities are also increasing with income.

4. The density of health care workers (number of workers) and intensity (what the workers do) increases with income.

RCA: Rich countries consume much more cutting edge health care technology (innovations). For every 1% increase in real income, we find a 1-3% increase in organ transplant operations, a 1-2% increase in pacemaker and ICD implants, a 1-2% increase in the density of medical imaging/diagnostic technology, and likely similar patterns for all manner of other new technologies (e.g., insulin pumps, ADHD prescriptions, etc.). Obviously, these indicators are just the tip of the iceberg. Still, where data of this sort are available, they tend to be highly consistent with extreme income elasticity (particularly newer, more expensive forms of health care). In the main, costs rise because this technological change tends to requires a lot more people in hospitals and providers’ offices to deliver this increasingly complicated array of health care (surgical procedures, diagnostics, drugs, therapies, etc.).

A bottom line is that health care spending in the United States is not exceptional once we take US income into account.

RCA’s analysis is consistent with the Baumol effect and my analysis with Helland in Why Are the Prices So Damn High (we have some minor differences with RCA on physician incomes but neither of our analyses depend on that point). A big point is that RCA and Helland and I argue that the rising price sectors are not crowding out consumption of other goods. We can and are buying more of other goods even as we spend more on health care and education. Or, as RCA puts it:

…these trends indicate that the rising health share is robustly linked with a generally constant long-term increase in real consumption across essentially all other major consumption categories.

It is true that the United States has a convoluted payment system which results in absurd and enraging bills. Fixing the pricing system could generate more equity and efficiency but RCA’s analysis tells us that billions are at stake, not trillions. A corollary is that as other countries reach current US levels of income their health care spending will look more like the United States does today.

See RCA for much more.