Results for “card krueger” 20 found

Where is the Card and Krueger paper at?

Has it held up better than many people believe? Here is a good and sure to prove controversial overview from Arindrajit Dube. Excerpt:

Subsequent research that built on Myth and Measurement has found that while the sizeable positive effects in some of their specifications were likely due to chance, the lack of job loss was very much a robust finding. Card and Krueger’s own subsequent analysis in 2000 using Unemployment Insurance filings by firms (which was closer to the universe of firms in the two states than their original sample) over a longer period already moved towards this view, as the employment elasticities, while still positive, were smaller in magnitude and not statistically distinguishable from zero.(1) My own work with William Lester and Michael Reich (2010) demonstrated this point by comparing contiguous counties across state borders and pooling over 64 different border segments with minimum wage differences over a 17-year period (1990-2006).

There is also a lengthy discussion of whether Neumark and Wascher overturned the central Card and Krueger result. Read the whole post.

Addendum: Tim Worstall comments. Matt Yglesias comments.

What about Card and Krueger?

Many of you have been asking this question. Robert Waldmann reports:

…what about Card and Krueger. Empirical estimates of the effect of the minimum wage on employment suggest that the effect is very small. One famous study by Card and Krueger showed a positive effect of an increase in the minimum wage. The logic used by Card and Krueger to understand how this could happen suggests that things are different now.

Their logic is basically that firms can choose to pay a low wage and have a high quit rate and take a long time to fill vacancies or pay a high wage and have fewer quits and fill vacancies more quickly. If they are forced to pay the higher wage, their desired level of employment will be lower, but that level is the sum of employment plus vacant jobs. A binding minimum wage can reduce the number of vacant jobs by more than it reduces the sum of employment plus vacant jobs. Thus more employment.

I think this is not relevant to the current situation. There are very few vacant jobs. Quit rates are low. According to their logic, the effect of the minimum wage on employment depends on the unemployment rate. The evidence of a small effect is almost all from periods of unemployment far below 10%. I don't think it is relevant to the current situation.

Waldmann makes other excellent points in his post, which is on the minimum wage more generally. I would add that there are many good critiques of the original study and the most plausible belief is still the traditional result, namely that minimum wage laws have a (slight) negative effect on employment.

A Nobel Prize for the Credibility Revolution

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of Card and Krueger (1994) (and here). The study is well known because of its paradoxical finding that New Jersey’s increase in the minimum wage in 1992 didn’t reduce employment at fast food restaurants and may even have increased employment. But what really made the paper great was the clarity of the methods that Card and Krueger used to study the problem.

The obvious way to estimate the effect of the minimum wage is to look at the difference in employment in fast food restaurants before and after the law went into effect. But other things are changing through time so circa 1992 the standard approach was to “control for” other variables by also including in the statistical analysis factors such as the state of the economy. Include enough control variables, so the reasoning went, and you would uncover the true effect of the minimum wage. Card and Krueger did something different, they turned to a control group.

Pennsylvania didn’t pass a minimum wage law in 1992 but it’s close to New Jersey so Card and Kruger reasoned that whatever other factors were affecting New Jersey fast food restaurants would very likely also influence Pennsylvania fast food restaurants. The state of the economy, for example, would likely have a similar effect on demand for fast food in NJ as in PA as would say the weather. In fact, the argument extends to just about any other factor that one might imagine including demographics, changes in tastes and changes in supply costs. The standard approach circa 1992 of “controlling for” other variables requires, at the very least, that we know what other variables are important. But by using a control group, we don’t need to know what the other variables are only that whatever they are they are likely to influence NJ and PA fast food restaurants similarly. Put differently NJ and PA are similar so what happened in PA is a good estimate of what would have happened in NJ had NJ not passed the minimum wage.

Thus Card and Kruger estimated the effect of the minimum wage in New Jersey by calculating the difference in employment in NJ before and after the law and then subtracting the difference in employment in PA before and after the law. Hence the term difference in differences. By subtracting the PA difference (i.e. what would have happened in NJ if the law had not been passed) from the NJ difference (what actually happened) we are left with the effect of the minimum wage. Brilliant!

Yet by today’s standards, obvious! Indeed, it’s hard to understand that circa 1992 the idea of differences in differences was not common. Despite the fact that differences in differences was actually pioneered by the physician John Snow in his identification of the causes of cholera in the 1840 and 1850s! What seems obvious today was not so obvious to generations of economists who used other, less credible, techniques even when there was no technical barrier to using better methods.

Furthermore, it’s less appreciated but not less important that Card and Krueger went beyond the NJ-PA comparison. Maybe PA isn’t a good control for NJ. Ok, let’s try another control. Some fast food restaurants in NJ were paying more than the minimum wage even before the minimum wage went into effect. Since these restaurants were always paying more than the minimum wage the minimum wage law shouldn’t influence employment at these restaurants. But these high-wage fast-food restaurants should be influenced by other factors influencing the demand for and cost of fast food such as the state of the economy, input prices, demographics and so forth. Thus, Card and Krueger also calculated the effect of the minimum wage by subtracting the difference in employment in high wage restaurants (uninfluenced by the law) from the difference in employment in low-wage restaurants. Their results were similar to the NJ-PA comparison.

The importance of Card and Krueger (1994) was not the result (which continue to be debated) but that Card and Krueger revealed to economists that there were natural experiments with plausible treatment and control groups all around us, if only we had the creativity to see them. The last thirty years of empirical economics has been the result of economists opening their eyes to the natural experiments all around them.

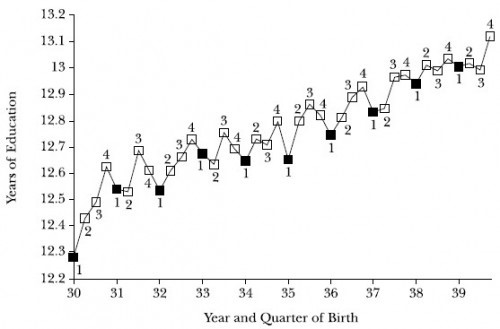

Angrist and Krueger’s (1991) paper Does Compulsory School Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings? Is one of the most beautiful in all of economics. It begins with a seemingly absurd strategy and yet in the light of a few pictures it convinces the reader that the strategy isn’t absurd but brilliant.

The problem is a classic one, how to estimate the effect of schooling on earnings? People with more schooling earn more but is this because of the schooling or is it because people who get more schooling have more ability? Angrist and Krueger’s strategy is to use the correlation between a student’s quarter of birth and their years of education to estimate the effect of schooling on earnings. What?! What could a student’s quarter of birth possibly have to do with how much education a student receives? Is this some weird kind of economic astrology?

Angrist and Krueger exploit two quirks of US education. The first quirk is that a child born in late December can start first grade earlier than a child, nearly the same age, who is born in early January. The second quirk is that for many decades an individual could quit school at age 16. Put these two quirks together and what you get is that people born in the fourth quarter are a little bit more likely to have a little bit more education than similar students born in the first quarter. Scott Cunningham’s excellent textbook on causal inference, The Mixtape, has a nice diagram:

Putting it all together what this means is that the random factor of quarter of birth is correlated with (months) of education. Who would think of such a thing? Not me. I’d scoff that you could pick up such a small effect in the data. But here come the pictures! Picture One (from a review paper, Angrist and Krueger 2001) shows quarter of birth and total education. What you see is that years of education are going up over time as it becomes more common for everyone to stay in school beyond age 16. But notice the saw tooth pattern. People who were born in the first quarter of the year get a little bit less education than people born in the fourth quarter! The difference is small, .1 or so of a year but it’s clear the difference is there.

Ok, now for the payoff. Since quarter of birth is random it’s as if someone randomly assigned some students to get more education than other students—thus Angrist and Krueger are uncovering a random experiment in natural data. The next step then is to look and see how earnings vary with quarter of birth. Here’s the picture.

Crazy! But there it is plain as day. People who were born in the first quarter have slightly less education than people born in the fourth quarter (figure one) and people born in the first quarter have slightly lower earnings than people born in the fourth quarter (figure two). The effect on earnings is small, about 1%, but recall that quarter of birth only changes education by about .1 of a year so dividing the former by the latter gives an estimate that implies an extra year of education increases earnings by a healthy 10%.

Lots more could be said here. Can we be sure that quarter of birth is random? It seems random but other researchers have found correlations between quarter of birth and schizophrenia, autism and IQ perhaps due to sunlight or food-availability effects. These effects are very small but remember so is the influence of quarter of birth on earnings so a small effect can still bias the results. Is quarter of birth as random as a random number generator? Maybe not! Such is the progress of science.

As with Card and Kruger the innovation in this paper was not the result but the method. Open your eyes, be creative, uncover the natural experiments that abound–this was the lesson of the credibility revolution.

Guido Imbens of Stanford (grew up in the Netherlands) has been less involved in clever studies of empirical phenomena but rather in developing the theoretical framework. The key papers are Angrist and Imbens (1994), Identification and Estimation of Local Treatment Effects and Angrist, Imbens and Rubin, Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables which answers the question: When we use an instrumental variable what exactly is it that we are measuring? In a study of the flu, for example, some doctors were randomly reminded/encouraged to offer their patients the flu shot. We can use the randomization as an instrumental variable to measure the effect of the flu shot. But note, some patients will always get a flu shot (say the elderly). Some patients will never get a flu shot (say the young). So what we are really measuring is not the effect of the flu shot on everyone (the average treatment effect) but rather on the subset of patients who got the flu shot because their doctor was encouraged–that latter effect is known as the local average treatment effect. It’s the treatment effect for those who are influenced by the instrument (the random encouragement) which is not necessarily the same as the effect of the flu shot on groups of people who were not influenced by the instrument.

By the way, Imbens is married to Susan Athey, herself a potential Nobel Prize winner. Imbens-Athey have many joint papers bringing causal inference and machine learning together. The Akerlof-Yellen of the new generation. Talk about assortative matching. Angrist, by the way, was the best man at the wedding!

A very worthy trio.

If you fear NIMBY, should you favor more immigration?

Many of today’s capitalists also want more immigration. Ocasio-Cortez also supports more immigration, which is confusing. According to Ricardo’s economic theory, expanding the population in the current environment will increase the cost of housing, health care, and higher education, just as it increased the price of wheat in the 19th century. This would hurt workers.

That is from Ronald W. Dworkin, “The New Rentiers: Ricardo Redux,” in the March/April 2019 issue of The American Interest, not yet on-line.

In general, facing up to the policy implications of a strict NIMBY world is something few wish to do. For instance, it seems to me that increases in the minimum wage, even if they initially went along Card-Krueger lines, would end up being passed along as greater benefits to landlords. All sorts of other attempts at amelioration could backfire as well.

Or do we live in some kind of intermediate NIMBY world on the coasts, where you get to complain about the land restrictions, but don’t have to live with the policy implications of strict NIMBY? Maybe so! But if so, I would like to see this argued for at more length.

The Evidence Is Piling Up That Higher Minimum Wages Kill Jobs

That is David Neumark in the WSJ, here is one excerpt:

Another recent study by Shanshan Liu and Thomas Hyclak of Lehigh University, and Krishna Regmi of Georgia College & State University most directly mimics the Dube et al. approach. But crucially it only uses as control areas parts of states that are classified by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as subject to the same economic shocks as the areas where minimum wages have increased. The resulting estimates point to job loss for the least-skilled workers studied, as do a number of other recent studies that address the Dube et al. criticisms.

The piece is a good brief survey of some of the developments since Card and Krueger. Here are some alternate links to the piece.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Taxing the rich.

2. “Exposure to import competition is bad for centrists.” (NYT)

3. Lifting the oil export ban is working.

4. The best all-purpose tweet, ever.

5. John Cochrane podcast with David Beckworth.

6. The debut of Chinese RoboCop.

7. Interview with Card and Krueger. Very good, goes well beyond previous coverage of their work and ideas.

How out of bounds is the $15 California minimum wage?

By 2022, when fully phased in (small firms with fewer than 25 workers would have until 2023 to comply), the California minimum wage would represent 69 percent of the median hourly wage in the state, assuming 2.2 percent annual growth from the current median of roughly $19 per hour.

That 69 percent ratio would be all but unprecedented, in U.S. terms and internationally. The current California minimum wage represents about half the state’s median hourly wage, just as the federal minimum wage averaged 48 percent of the national median between 1960 and 1979, according to a 2014 Brookings Institution paper by economist Arindrajit Dube. (It is currently 38 percent of the national median.)

Other industrial democracies with statutory minimum wages typically set theirs at half the national median wage, too.

That is from Charles Lane. This is also worth noting:

Dube, generally a supporter of minimum wages, recommended that states use 50 percent of the median as their benchmark in the United States. (He told me by email that California’s experiment is worth running and monitoring.)

Yet Alan Krueger, among many others, is against it. On what grounds is it worth running?

The minimum wage and the Great Recession

I believe Card and Krueger will and should win Nobel Prizes, but their work is also not the last word on the minimum wage, especially during weak labor markets. Here is the most recent study, by Jeffrey Clemens:

I analyze recent federal minimum wage increases using the Current Population Survey. The relevant minimum wage increases were differentially binding across states, generating natural comparison groups. I first estimate a standard difference-in-differences model on samples restricted to relatively low-skilled individuals, as described by their ages and education levels. I also employ a triple-difference framework that utilizes continuous variation in the minimum wage’s bite across skill groups. In both frameworks, estimates are robust to adopting a range of alternative strategies, including matching on the size of states’ housing declines, to account for variation in the Great Recession’s severity across states. My baseline estimate is that this period’s full set of minimum wage increases reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with less than a high school education by 5.6 percentage points. This estimate accounts for 43 percent of the sustained, 13 percentage point decline in this skill group’s employment rate and a 0.49 percentage point decline in employment across the full population ages 16 to 64.

Do any of you see an ungated version? In any case I hope this receives the media attention it deserves. Will it?

Assorted links

1. Nudging people to decrease their credit card spending.

2. Edmond Malinvaud passed away a few days ago, here is an Alan Krueger interview with him.

3. “Dried tardigrades have been brought back to life after eight years.”

4. Paul Krugman argues you sometimes should reason from a price change. And Scott in response.

5. Have American hospitals actually been on a productivity binge?

6. How TripAdvisor is changing travel, from Tom Vanderbilt.

Thomson Reuters predicts the 2013 Nobel Laureate in economics

Joshua D. Angrist, David E. Card, Alan B. Krueger, Sir David F. Hendry, M. Hashem Pesaran, Peter C.B. Phillips, Sam Peltzman, and Richard A. Posner, all very good possible picks in my view.

My personal prediction (which never once has been correct, at least not in the proper year) is for an early “shock” prize to Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer, in part to show (try to show?) that economics really is an actual science.

In any case the above link offers Reuters picks for the science prizes as well. Here are some other speculations for the science prizes as well.

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Interpreting Statistical Evidence

Betsey Stevenson & Justin Wolfers offer six principles to separate lies from statistics:

1. Focus on how robust a finding is, meaning that different ways of looking at the evidence point to the same conclusion.

In Why Most Published Research Findings are False I offered a slightly different version of the same idea

Evaluate literatures not individual papers.

SWs second principle:

2. Data mavens often make a big deal of their results being statistically significant, which is a statement that it’s unlikely their findings simply reflect chance. Don’t confuse this with something actually mattering. With huge data sets, almost everything is statistically significant. On the flip side, tests of statistical significance sometimes tell us that the evidence is weak, rather than that an effect is nonexistent.

That’s correct but there is another point worth making. Tests of statistical significance are all conditional on the estimated model being the correct model. Results that should happen only 5% of the time by chance can happen much more often once we take into account model uncertainty not just parameter uncertainty.

3. Be wary of scholars using high-powered statistical techniques as a bludgeon to silence critics who are not specialists. If the author can’t explain what they’re doing in terms you can understand, then you shouldn’t be convinced.

I am mostly in agreement but SW and I are partial to natural experiments and similar methods which generally can be explained to the lay public while other econometricians (say of the Heckman school) do work that is much more difficult to follow without significant background and while being wary I also wouldn’t reject that kind of work out of hand.

4. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking about an empirical finding as “right” or “wrong.” At best, data provide an imperfect guide. Evidence should always shift your thinking on an issue; the question is how far.

Yes, be Bayesian. See Bryan Caplan’s post on the Card-Krueger minimum wage study for a nice example.

5. Don’t mistake correlation for causation.

Does anyone still do this? I know the answer is yes. I often find, however, that the opposite problem is more common among relatively sophisticated readers–they know that correlation isn’t causation but they don’t always appreciate that economists know this and have developed sophisticated approaches to disentangling the two. Most of the effort in a typical empirical paper in economics is spent on this issue.

6. Always ask “so what?” …The “so what” question is about moving beyond the internal validity of a finding to asking about its external usefulness.

Good advice although I also run across the opposite problem frequently, thinking that a study done in 2001 doesn’t tell us anything about 2013, for example.

Here, from my earlier post, are my rules for evaluating statistical studies:

1) In evaluating any study try to take into account the amount of background noise. That is, remember that the more hypotheses which are tested and the less selection which goes into choosing hypotheses the more likely it is that you are looking at noise.

2) Bigger samples are better. (But note that even big samples won’t help to solve the problems of observational studies which is a whole other problem).

3) Small effects are to be distrusted.

4) Multiple sources and types of evidence are desirable.

5) Evaluate literatures not individual papers.

6) Trust empirical papers which test other people’s theories more than empirical papers which test the author’s theory.

7) As an editor or referee, don’t reject papers that fail to reject the null.

More on the returns to education

First, apologies to Arnold, I missed his post when traveling and so he does discuss natural experiments, contrary to my previous claim about EconLog bloggers. That said, I’m not so happy with his analysis. He’s taking a few of the papers he sees as the weakest and he explains why they are weak. I would rather he dissects the strongest pieces and compares them to the strongest pieces, using natural experiments, showing very low rates of return to education. The Joshua Angrist papers (often with Alan Krueger) for instance are quite sophisticated and do not run afoul of Arnold’s objections. In works such as this (later versions seem to be gated), Angrist and Krueger perform exactly the natural experiment which Arnold requests and they find high (marginal) returns to education. Or see this piece by Card.

Here is Bryan’s response to my post. Focus on his #2, which is the crux of the matter:. He cites the signaling motives for education and concludes: “Here, the evidence Tyler cites is simply irrelevant.” This is simply not true and indeed these papers are obsessed with distinguishing learning effects from preexisting human capital differences. That is what these papers are, so to speak. In that context, “ability bias” in the estimates doesn’t seem to be very large, see for instance the Angrist or Card pieces linked to above. This paper surveys some of the “adjusting for ability bias” literature; it is considered quite “pessimistic” (allows for a good deal of signaling, in Caplan’s terminology) and still it finds a positive five percent a year real productivity gain from an extra year of schooling.

What’s striking about the work surveyed by Card is how many different methods are used and how consistent their results are. You can knock down any one of them (“are identical twins really identical?, etc.), but at the end of the day which are the pieces — using natural or field experiments — standing on the other side of the scale? The Card results are also consistent with theory, namely that models which emphasize signaling imply large unrealized gains from trade; it’s not that hard for an employer to administer an implicit IQ test as Google and Microsoft do all the time. As a separate (and here undocumented) point, I would argue the Angrist and Card results are consistent with the bulk of results from sociological and anthropological investigations.

There really does seem to be a professional consensus. Maybe it’s wrong, and/or dominated by biased pro-education specialists, but I’m not seeing very strong arguments against it. For the time being at least, I don’t see that there is much anywhere else to go with one’s beliefs. If Arnold or Bryan (or David) suggests a good paper with a natural experiment showing a low marginal ROR for education, I am happy to read the paper and report back and compare it to the preponderance of evidence on the other side.

The real puzzle is how large measured marginal returns to education are consistent with the continuing observed failures of the American educational system. Why does the low-hanging fruit persist or is it low-hanging at all? The traditional liberal view is that further educational subsidies are needed, but a possible alternative is that some people simply do not wish to step across to the other side of the divide to a “better life,” at least as defined by middle class values and income statistics. Or is there some other hypothesis? Whichever way you cut it, a big improvement in this area does not seem about to happen and arguably we are moving in the opposite direction. Whatever gains are there “in the data,” we don’t seem able or willing to capture them.

How much good could health care monopsony do?

Greg Mankiw has an interesting column on the public plan option; you've already seen related points on his blog and on MR.

Today I'm interested in a slightly different question, namely the potential benefits of monopsony. Imagine a benevolent single buyer of health care services. Forget about whether or not it could be a government; let's just focus on the logic of the model. I can think of a few scenarios:

1. The buyer bargains down price and suppliers in turn lower quantity.

2. The buyer bargains down price and the monopolizing suppliers respond by expanding quantity. The monopsonist moves us to a more competitive solution. Note that under this option the direct institution of more competition could have the same effects.

If #2 is true, you might expect supply restrictions to be an important issue. That is, the people who favor monopsony should also favor greater competitiveness on the supply side. Yet this does not seem like a current priority. I hardly ever see talk of deregulating medical licensing, allowing paramedics and nurses to perform more basic medical functions, or abolishing other entry restrictions. I do recall that an earlier version of Obama's plan, struck down by Congress, would have created a nationwide insurance market. There was no big fight, either in the administration or in the blogosphere.

Those who favor monopsony might have another model in mind. In this model there are many medical suppliers but each supplier still has a fair degree of ex post monopoly power. Search costs, non-transparency, lock-in, and consumer irrationality can generate this kind of result. And in these models allowing for more entry needn't much help the basic problem.

Under #2, which other policies will help set this market right? What are the possible policy substitutes for monopsony?

And in #2, what happens if a monopsonist third party payer bargains prices down? What are the offsetting quality responses? Are monopsonists good at bargaining for higher levels of quality? Or might the all-in-one, bureaucratic nature of the monopsonistic enterprise mean that the monopsonist is very good at bargaining over price (measurable) and very bad at bargaining over quality (harder to measure and verify and we already know there is irrationality, non-transparency, lock-in, etc).

If we put monopsony in place, can a version of the Card-Krueger monopsony model apply to medicine, namely a welfare-improving minimum wage for doctors, albeit at a very high level? That would mean we don't want the monopsony to economize on how much we spend on health care.

For all the recent writings on health care, these questions remain underexplored. Comments are open, but today I'm not interested in the usual bickering about public vs. private sector. I'd like to hear about the logic of monopsony.

Sadly, the average economist is no Milton Friedman.

It beggars belief when economists at Princeton, Harvard and Berkeley claim that they are lone voices in the wilderness boldly striking heterodox positions against the hegemony of “free market economics.”

David Card, for example, says “You lose your ticket as a certified economist if you don’t say any kind of price regulation is bad and free trade is good.” Really? Card and Krueger’s famous paper on the minimum wage was a 1993 NBER working paper published in the AER in 1994. What happened then in 1995? Was Card decertified, drummed out of the profession, vilified by his peers? Hardly, in 1995 David Card was honored (deservedly imho) by the American Economic Association with the John Bates Clark medal.

Dani Rodrik says “I fall into the methods of the mainstream, but not the faith,” which he defines as the belief that more markets and free trade are always good and government regulation is always bad. Give me a break. Let’s go to the data.

Klein and Stern surveyed members of the AEA on a host of policy questions bearing on markets and government regulation. The result, “Only a small percentage of AEA members ought to be called supporters of free-market principles.”

Even on the minimum wage, support for which Card says gets you decertified, the mean economist position is in between “support mildly” and “have mixed feelings.” Indeed, even Card has mixed feelings about the minimum wage! (See his book with Krueger in which he points out that the minimum wage is not a very effective way to help the poor). On a host of other issues concerning government regulation, like support for OSHA, the FDA, and the EPA, the mean economist is somewhere between strongly and mildly support.

Only on free trade is there strong opposition to government regulation in the form of tariffs. Thank goodness for small mercies.

The new attack on free trade

It is by Erik Reinert, How Rich Countries Got Rich, and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor; here is a home page for the book. The title is misleading and sounds too monocausal. Reinert’s well-written book in fact revives the arguments of Friedrich List, Henry Carey, and the 19th century protectionists. In his view many forms of manufacturing are increasing returns to scale activities and help support civil society in the longer run. Agriculture and the sale of raw materials are "Malthusian" sectors with diminishing returns and they are unable to create a stable middle class. The solution of course is to stop pushing free trade upon the third world and thus allow it to develop. Reinert claims Tudor England, 19th century America (though see Doug Irwin’s revisionist work), Bismarckian Germany, and pre-reform Latin America as data points on his side. Unlike many critics of free trade, he does fully understand Ricardian and other theories of comparative advantage.

I don’t think his main claims are crazy and they are by no means theoretically impossible. I wish however he had devoted more attention to the following:

1. Many other preconditions — most of all educational potential and some decent institutions — must be in place for tariffs to spur economic development in this manner. Not all regions can create sustainable increasing returns to scale industries in manufacturing, tariffs or not.

2. Reinert cites many historical examples but doesn’t establish that they all apply, or apply with the force he suggests. The book is a polemic, as might be written by an advocate of free trade.

3. On average the free-trading poor nations have had higher growth rates than the protectionists; see the work of Anne Krueger. India is one obvious case of a miscalculated protectionism.

4. More often than not, tariffs and trade protection are abused for purposes of corruption and special interests.

5. Reinert himself stresses that the proper growth path requires a later move to free trade. This development is by no means automatic, given that protectionism creates its own special interests.

I’m still not sure why Dani Rodrik thinks that invoking 4 and 5 amounts to playing politics, or guessing at politics, at the expense of substantive economics. I think of it as citing a downward-sloping demand curve in the time-honored tradition of political economy and public choice. Like so much of modern economic thought, it comes from Adam Smith.

No economist says "I favor a philosopher-King and here is what he should do. I can’t tell you what he will do, that is politics." Sub in "protectionist trade policy" for "a philosopher-King" and decide whether this sentence makes any more sense.