Results for “frank dikotter” 5 found

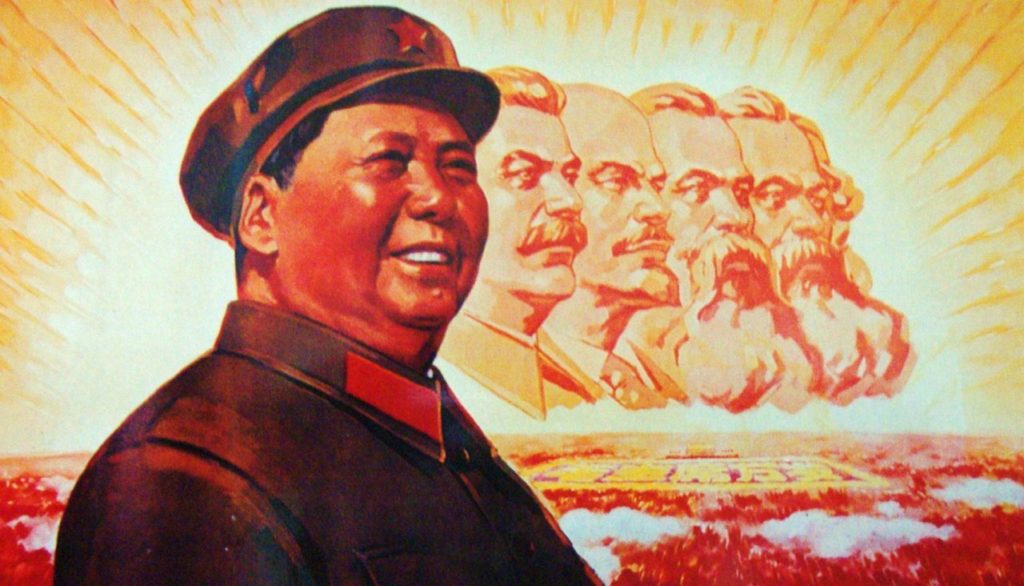

Mao’s Crimes Against Humanity

From Frank Dikötter’s short note at History Today:

In the People’s Republic of China, archives do not belong to the people, they belong to the Communist Party. They are often housed in a special building on the local party committee premises, which are generally set among lush and lovingly manicured grounds guarded by military personnel. Access would have been unthinkable until a decade or so ago, but over the past few years a quiet revolution has been taking place, as increasing quantities of documents older than 30 years have become available for consultation to professional historians armed with a letter of recommendation. The extent and quality of the material varies from place to place, but there is enough to transform our understanding of the Maoist era.

…What comes out of this massive and detailed dossier is a tale of horror in which Mao emerges as one of the greatest mass murderers in history, responsible for the deaths of at least 45 million people between 1958 and 1962. It is not merely the extent of the catastrophe that dwarfs earlier estimates, but also the manner in which many people died: between two and three million victims were tortured to death or summarily killed, often for the slightest infraction. When a boy stole a handful of grain in a Hunan village, local boss Xiong Dechang forced his father to bury him alive. The father died of grief a few days later. The case of Wang Ziyou was reported to the central leadership: one of his ears was chopped off, his legs were tied with iron wire, a ten kilogram stone was dropped on his back and then he was branded with a sizzling tool – punishment for digging up a potato.

…Fresh evidence is also being unearthed on the land reform that transformed the countryside in the early 1950s. In many villages there were no ‘landlords’ set against ‘poor peasants’ but, rather, closely knit communities that jealously protected their land from the prying eyes of outsiders – the state in particular. By implicating everybody in ‘accusation meetings’ – during which village leaders were humiliated, tortured and executed while their land and other assets were redistributed to party activists recruited from local thugs and paupers – the communists turned the power structure upside down. Liu Shaoqi, the party’s second-in-command, had a hard time reining in the violence, as a missive from the Hebei archives shows: ‘When it comes to the ways in which people are killed, some are buried alive, some are executed, some are cut to pieces, and among those who are strangled or mangled to death, some of the bodies are hung from trees or doors.’

*The Tragedy of Liberation*

That is the new book by Frank Dikötter, the subtitle is A History of the Chinese Revolution 1945-1957, and it is a prequel to his earlier Mao’s Great Famine. His books are superb documents of the tyrannical age he studies. Here is one excerpt:

In an orgy of false accusations and arbitrary denunciations, few escaped with their reputations intact. By February no more than 10,000 of a total 50,000 ‘capitalists’ in Beijing were considered honest. Similar figures came from other parts of the country. To punish all would wreck the economy. Mao had a solution to this conundrum. He came up with a quota, ordering that a few should be killed to set the tone, while exemplary punishment should focus on 5 per cent of the most ‘reactionary’ suspects. Across most cities, by a rough rule of thumb, about 1 per cent of the accused were shot, a further 1 per cent sent to labour camps for life, and 2 to 3 per cent imprisoned for terms of ten years or more.

This is not easy material to read about, but Dikötter’s books are landmark achievements of their time.

And as I am wont to say, China’s prospects and fundamentals look pretty good if you scrutinize the country’s history over the last 30 or also the last 3000 years. It’s the time frame of the last 300 years that doesn’t look so good.

The rickshaw was (possibly) invented by a Westerner

The rickshaw was invented in 1868 by John Goble, an American missionary living in Tokyo.

The source is Frank Dikötter, Things Modern: Material Culture and Everyday Life in China, which is also a good book. Wikipedia offers a more complex story about the possible inventors, with some candidates for the inventor being Japanese. In any case, I had thought of it as a more ancient device than it turns out to be.

China fact (book) of the day

When it comes to the overall death toll, for instance, researchers so far have had to extrapolate from official population statistics…Their estimates range from 15 to 32 million excess deaths. But the public security reports compiled at the time, as well as the voluminous secret reports collated by party committees in the last months of the Great Leap Forward, show how inadequate these calculations are, pointing instead at a catastrophe of a much greater magnitude: this book shows that at least 45 million people died unnecessarily between 1958 and 1962.

That is from Frank Dikötter's Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962, which is one of the scariest books I have read. Here is another passage, I am not sure how well it is sourced:

Mao was delighted. As reports came in from all over the country about new records in cotton, rice, wheat or peanut production, he started wondering what to do with all the surplus food. On August 4 1958 in Xushui, flanked by Zhang Guozhong, surrounded by journalists, plodding through the fields in straw hat and cotton shoes, he beamed: "How are you going to eat so much grain? What are you going to do with the surplus?"

"We can exchange it for machinery," Zhang responded after a pause for thought.

[Showing a poor understanding of Say's Law] "But you are not the only one to have a surplus, others too have too much grain! Nobody will want your grain!" Mao shot back with a benevolent smile.

"We can make spirits of out of taro," suggested another cadre.

"But every county will make spirits! How many tonnes of spirits do we need? Mao mused. "With so much grain, in future you should plant less, work half time and spend the rest of your time on culture and leisurely pursuits, open schools and a university, don't you think?…You should eat more. Even five meals a day is fine!"

Here are some reviews of the book.

What I’ve been reading

1. Jason Brennan, Against Democracy. He is a epistocrat. P.S. voters are ignorant and irrational. Furthermore “Politics is not a Poem.” I agree with most of the debunking arguments in this book, but I am not convinced epistocracy ends up being better; Brennan’s examples of epistocracy include restricted franchise, plural voting, voting by lottery, epistocratic veto (the Senate, but more so), and weighted voting. I see big advantages to a strict normative ideal of legal egalitarianism of civic rights, and I suspect that ends up meaning some form of democracy, albeit constrained by the overlay of a constitutional republic.

2. Ji Xianlin, The Cowshed: Memoirs of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The classic account of its kind, in this edition brilliantly translated and presented.

And I am happy to praise Frank Dikötter’s The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History 1962-1976, but I did not find it as revelatory as his earlier books on China. Here is a Judith Shapiro NYT review.

3. Aileen M. Kelly, The Discovery of Chance: The Life and Thought of Alexander Herzen. Beautifully written, and full of interesting history, but it never quite convinces the reader that Herzen is an interesting and worthwhile intellect for 2016. Maybe he isn’t — does that make this book better or worse?

David L. Ulin’s Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles is a meditation on to what extent Los Angeles succeeds as a walkable city, or someday might get there.

There is Don Watkins and Yaron Brook, Equal is Unfair: America’s Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality, by no means do I go all the way with them, but still this a useful corrective to some current obsessions.

Don and Alex Tapscott, Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin is Changing Money, Business, and the World lists more possible uses for blockchains than you would have thought possible.

James T. Bennett, Subsidizing Culture: Taxpayer Enrichment of the Creative Class, the subtitle says it all.