Results for “moskos” 8 found

Moskos on Surging Crime in NYC

Peter Moskos warns about rising crime in NYC in the NYDaily news.

Violence in New York is up….In the last 28 days (through July 12), compared to last year, shootings have more than tripled (318 vs. 97). Last week was even worse. If the last 28 days become the new normal, 2021 will have more than 4,100 shootings, a level not seen in well over 20 years.

Undoubtedly bail reform, protests, looting, COVID-19, and the release of prisoners because of COVID all play a role, though how much is debate. What’s less known is how the NYPD has been methodically declawed by design.

Years of political advocacy have resulted in the intentional erosion of legal police authority. There is less prosecution. Most miscreant activities have been decriminalized. The city survived and even benefited from many reforms, but now the camel’s back is breaking.

…For many, this is a feature, not a flaw. A new breed of progressive prosecutors has battled to see who can prosecute the least. As a result, arrests in 2019 decreased 35% from 2016. Reducing incarceration is desirable, and New York has been doing so literally for decades without jeopardizing public safety.

More recently, since November, because of bail reform and COVID releases, the number of jailed inmates dropped another 40%. People are coming out of jail, and few are going in. Many applaud this because incarceration disproportionately affects Black and Brown people.

But so does non-enforcement and the rise in violence. In 2018 (the latest year with published data), 95.7% of shooting victims in New York City are Black or Hispanic. Just 4.3% of victims are white or Asian. When violence goes up, more Black and Hispanic people are shot.

Misdemeanor Prosecution

Misdemeanor Prosecution (NBER) (ungated) is a new, blockbuster paper by Agan, Doleac and Harvey (ADH). Misdemeanor crimes are lesser crimes than felonies and typically carry a potential jail term of less than one year. Examples of misdemeanors include petty theft/shoplifting, prostitution, public intoxication, simple assault, disorderly conduct, trespass, vandalism, reckless driving, indecent exposure, and various drug crimes such as possession. Eighty percent of all criminal justice cases, some 13 million cases a year, are misdemeanors. ADH look at what happens to subsequent criminal behavior when misdemeanor cases are prosecuted versus non-prosecuted. Of course, the prosecuted differ from the non-prosecuted so we need to find situations where for random reasons comparable people are prosecuted and non-prosecuted. Not surprisingly some Assistant District Attorneys (ADAs) are more lenient than others when it comes to prosecuting misdemeanors. ADH use the random assignment of ADAs to a case to tease out the impact of prosecution–essentially finding two similar individuals one of whom got lucky and was assigned a lenient ADA and the other of whom got unlucky and was assigned a less lenient ADA.

We leverage the as-if random assignment of nonviolent misdemeanor cases to Assistant District Attorneys (ADAs) who decide whether a case should move forward with prosecution in the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in Massachusetts.These ADAs vary in the average leniency of their prosecution decisions. We find that,for the marginal defendant, nonprosecution of a nonviolent misdemeanor offense leads to large reductions in the likelihood of a new criminal complaint over the next two years.These local average treatment effects are largest for first-time defendants, suggesting that averting initial entry into the criminal justice system has the greatest benefits.

… We find that the marginal nonprosecuted misdemeanor defendant is 33 percentage points less likely to be issued a new criminal complaint within two years post-arraignment (58% less than the mean for complier” defendants who are prosecuted; p < 0.01). We find that nonprosecution reduces the likelihood of a new misdemeanor complaint by 24 percentage points (60%; p < 0.01), and reduces the likelihood of a new felony complaint by 8 percentage points (47%; not significant). Nonprosecution reduces the number of subsequent criminal complaints by 2.1 complaints (69%; p < .01); the number of subsequent misdemeanor complaints by 1.2 complaints (67%; p < .01), and the number of subsequent felony complaints by 0.7 complaints (75%; p < .05). We see significant reductions in subsequent criminal complaints for violent, disorderly conduct/theft, and motor vehicle offenses.

Did you get that? On a wide variety of margins, prosecution leads to more subsequent criminal behavior. How can this be?

We consider possible causal mechanisms that could be generating our findings. Cases that are not prosecuted by definition are closed on the day of arraignment. By contrast, the average time to disposition for prosecuted nonviolent misdemeanor cases in our sample is 185 days. This time spent in the criminal justice system may disrupt defendants’ work and family lives. Cases that are not prosecuted also by definition do not result in convictions, but 26% of prosecuted nonviolent misdemeanor cases in our sample result in a conviction. Criminal records of misdemeanor convictions may decrease defendants’ labor market prospects and increase their likelihoods of future prosecution and criminal record acquisition, conditional on future arrest. Finally, cases that are not prosecuted are at much lower risk of resulting in a criminal record of the complaint in the statewide criminal records system. We find that nonprosecution reduces the probability that a defendant will receive a criminal record of that nonviolent misdemeanor complaint by 55 percentage points (56%, p < .01). Criminal records of misdemeanor arrests may also damage defendants’ labor market prospects and increase their likelihoods of future prosecution and criminal record acquisition, conditional on future arrest. All three of these mechanisms may be contributing to the large reductions in subsequent criminal justice involvement following nonprosecution.

So should we stop prosecuting misdemeanors? Not necessarily. Even if prosecution increases crime by the prosecuted it can still lower crime overall through deterrence. In fact, since there are more people who are potentially deterred than who are prosecuted, general deterrence can swamp specific deterrence (albeit there are 13 million misdemeanors so that’s quite big). The authors, however, have gone some way towards addressing this objection because they combine their “micro” analysis with a “macro” analysis of a policy experiment.

During her 2018 election campaign, District Attorney Rollins pledged to establish a presumption of nonprosecution for 15 nonviolent misdemeanor offenses…After the inauguration of District Attorney Rollins, nonprosecution rates rose not only for cases involving the nonviolent misdemeanor offenses on the Rollins list, but also for those involving nonviolent misdemeanor offenses not on the Rollins list (and for all nonviolent misdemeanor cases)…. the increases in nonprosecution after the Rollins inauguration led to a 41 percentage point decrease in new criminal complaints for nonviolent misdemeanor cases on the Rollins list (not significant), a 47 percentage point decrease in new criminal complaints for nonviolent misdemeanor cases not on the Rollins list (p < .05), and a 56 percentage point decrease in new criminal complaints for all nonviolent misdemeanor cases (p < .05).

It’s unusual and impressive to see multiple sources of evidence in a single paper. (By the way, this paper is also a great model for learning all the new specification tests and techniques in the “leave-out” literature, exogeneity, relevance, exclusion restriction, monotonicity etc. all very clearly described.)

The policy study is a short-term study so we don’t know what happens if the rule is changed permanently but nevertheless this is good evidence that punishment can be criminogenic. I am uncomfortable, however, with thinking about non-prosecution as the choice variable, even on the margin. Crime should be punished. Becker wasn’t wrong about that. We need to ask more deeply, what is it about prosecution that increases subsequent criminal behavior? Could we do better by speeding up trials (a constitutional right that is often ignored!)–i.e. short, sharp punishment such as community service on the weekend? Is it time to to think about punishments that don’t require time off work? What about more diversion to programs that do not result in a criminal record? More generally, people accused and convicted of crimes ought to find help and acceptance in re-assimilating to civilized society. It’s crazy–not just wrong but counter-productive–that we make it difficult for people with a criminal record to get a job and access various medical and housing benefits.

The authors are too sophisticated to advocate for non-prosecution as a policy but it fits with the “defund the police,” and “end cash bail” movements. I worry, however, that after the tremendous gains of the 1990s we will let the pendulum swing back too far. A lot of what counts as cutting-edge crime policy today is simply the mood affiliation of a group of people who have no recollection of crime in the 1970s and 1980s. The great forgetting. It’s welcome news that we might be on the wrong side of the punishment Laffer curve and so can reduce punishment and crime at the same time. But it’s a huge mistake to think that the low levels of crime in the last two decades are a permanent features of the American landscape. We could lose it all in a mistaken fit of moralistic naivete.

In Baltimore Arrests are Down and Crime is Way Up

A debate forum at the New York Times begins:

A rise in gun violence in New York, Baltimore and other cities after months of angry protests over police killings of unarmed black men, have led some to see a ”Ferguson effect,” in which police, spooked by criticism of aggressive tactics, have pulled back, making fewer arrests and fewer searches for weapons.

But has a wave of murders and shootings brought an end to the long drop in crime?

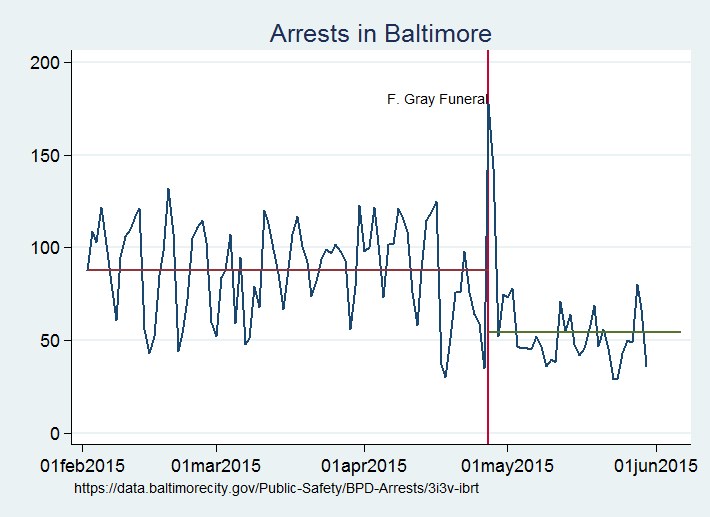

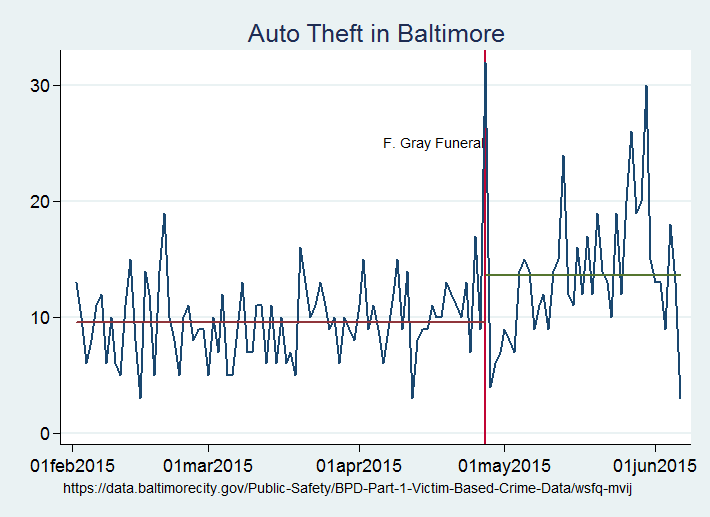

I don’t think that we will see a sustained increase in crime at the national level. But there is no question that we are seeing a Ferguson effect in Baltimore–more precisely a Freddie Gray effect. Arrests in Baltimore have fallen by nearly 40% since Freddie Gray’s funeral and the start of the riots on April 27. In the approximately 3 months before the Gray funeral police made an average of 87.7 arrests per day, since that time they have made only 54.6 arrests a day on average (up to May 30, most recent data).

As Peter Moskos argues:

In Baltimore today, several police officers need to respond to situations where formerly one could do the job. This stretches resources and prevents proactive policing.

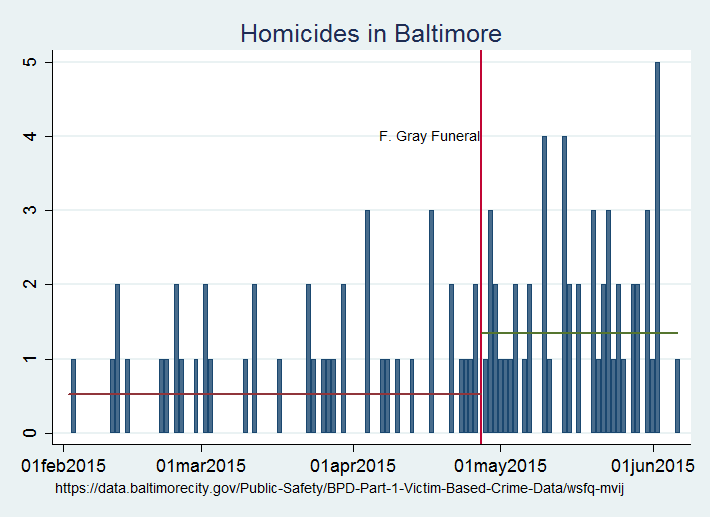

Not all arrests are good arrests, of course, but the strain is cutting policing across the board and the criminals are responding to incentives. Fewer police mean more crime. As arrests have fallen, homicides, shootings, robberies and auto thefts have all spiked upwards. Homicides, for example, have more than doubled from .53 a day on average before the unrest to 1.35 a day after (up to June 6, most recent data)–this is an unprecedented increase–and the highest homicide rate Baltimore has ever seen.

Put differently, the unrest in Baltimore and subsequent reduction in policing is responsible for roughly twenty “excess” deaths. (so far)

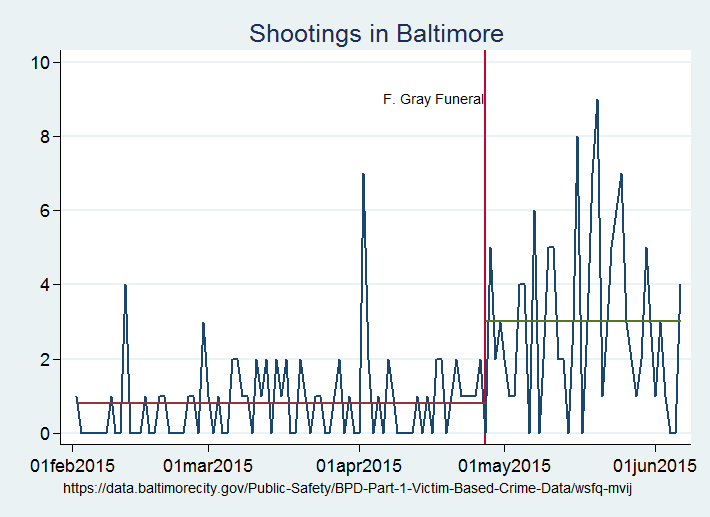

It’s not just homicides, the number of shootings in Baltimore has more than tripled. Shootings increased from .82 a day before the unrest to just over 3 a day. Since the onset of the riots there has hardly been a day without a shooting.

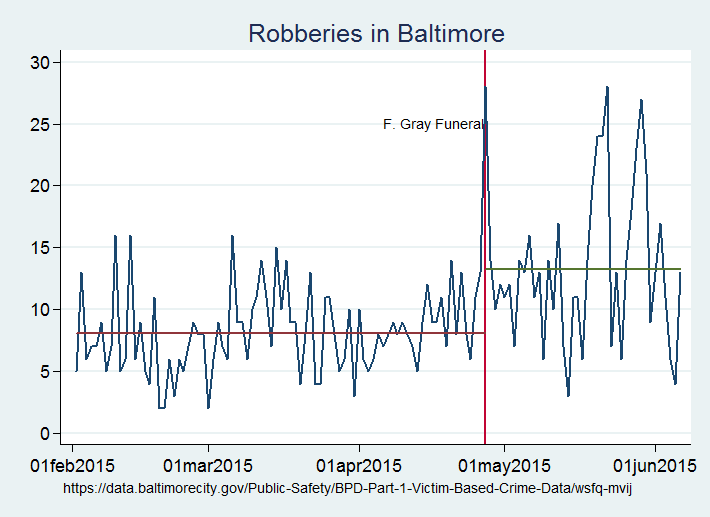

Robberies are up from 8.1 per day to 13.25 per day on average.

Even auto thefts are up from 9.6 per day to 13.6 per day on average.

The increase in homicides and other crime is terrible and it is also putting a strain on police resources.

Police Commissioner Anthony W. Batts said the rise in killings is “backlogging” investigators, just as the community has become less engaged with police, providing fewer tips.

With luck the crime wave will subside quickly but the longer-term fear is that the increase in crime could push arrest and clearance rates down so far that the increase in crime becomes self-fulfilling. The higher crime rate itself generates the lower punishment that supports the higher crime rate (see my theory paper). In the presence of multiple equilibria it’s possible that a temporary shift could push Baltimore into a permanently higher high-crime equilibrium. Once the high-crime equilibrium is entered it may be very difficult to exit without a lot of resources that Baltimore doesn’t have. I have long argued that high-crime areas need more police but the tragedy is that they also need high-quality policing and that too is made more difficult to achieve by strained budgets and strained police.

Solitary Confinement

In the United States, approximately 100,000 prisoners are kept in solitary confinement. Colin Dayan reports:

Prisoners there are locked alone in their cells for 23 hours a day. Their food is delivered through a slot in the door of their 80-square-foot cell. They stare at unpainted concrete walls onto which nothing can be put. They look through doors of perforated steel, what one officer described to me as “irregular-shaped Swiss cheese.” Except for the occasional touch of a guard’s hand as they are handcuffed and chained when they leave their cells, they have no contact with another human being.

In this condition of enforced idleness, prisoners are not eligible for vocational programs. They have no educational opportunities; books and newspapers are severely limited; post and telephone communication virtually nonexistent. Locked in their cells for as many as 161 of the 168 hours in a week, they spend most of the brief time out of their cells in shackles, with perhaps as much as eight minutes to shower. An empty exercise room — a high-walled cage with a mesh screening overhead, also known as the “dog pen” — is available for “recreation.”

These are locales for perpetual incapacitation, where obligations to society, the duties of husband, father or lover are no longer recognized. An inmate wrote me, “People go crazy here in lockdown. People who weren’t violent become violent and do strange things. This is a city within a city, another world inside of a larger one where people could care less about what goes on in here. This is an alternate world of hate, pain, and mistreatment.”

Occasionally, solitary confinement may be necessary to separate prisoners but why forbid books and newspapers? This is retribution not deterrence. Indeed, as Peter Moskos has argued, physical punishment would be a better deterrent and more humane.

Hat tip: Robin Hanson.

Assorted Links

1. In defense of flogging by Peter Moskos. I was pretty sure I wrote something like this a few years ago but after a search all I could find was this post on sex and spanking.

2. Google lobbies Nevada to allow Self-Driving Cars. The future isn’t here until suddenly it is. FYI, texting while in the “driver’s” seat would be made legal in such cars.

3. Used car prices are rising so much that many models are selling for more today than a year ago.

4. Conor Friedersdorf’s Nearly 100 Fantastic Pieces of Journalism.

Million dollar blocks

An innovative analysis by Eric Cadora highlights "million-dollar blocks" — individual city blocks where more than one million dollars per block per year are spent to incarcerate individuals from that block. Some blocks cost over five million dollars per year…A million dollars, coincidentally, is roughly what it would cost to pay for one patrol officer, twenty-four hours a day, every day for one year.

That is from Peter Moskos’s Cop in the Hood: My Year Spent Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District. In Brooklyn of 2003, there were 35 million dollar blocks. Here is more information, plus maps and graphs.

Car patrol vs. foot patrol

Car patrol eliminated the neighborhood police officer. Police were pulled off neighborhood beats to fill cars. But motorized patrol — the cornerstone of urban policing — has no effect on crime rates, victimization, or public satisfaction. Lawrence Sherman was an early critic of telephone dispatch and motorized patrol, noted, "The rise of telephone dispatch transformed both the method and purpose of patrol. Instead of watching to prevent crime, motorized police patrol became a process of merely waiting to respond to crime."

That is from Peter Moskos’s Cop in the Hood: My Year Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District; here is my previous post on the book.

Cop in the Hood

Motivated primarily by a desire for court overtime pay, police officers want arrests on their own terms, ideally without victims, complaints, or unnecessary paperwork. Young officers make more arrests than veteran officers. These officers believe that making arrests is police work. In my squad, the top three officers in arrest totals were three officers with the least experience. An arrest-based culture can exist in a low-drug environment, but without a limitless supply of arrestable criminal offenders, an arrest-based culture cannot make a lot of arrests. Neighborhoods, without public drug dealings will not produce a high number of arrests.

That is from Peter Moskos’s truly excellent Cop in the Hood: My Year Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District. This is one of the two or three best conceptual analyses of "cops and robbers" I have read. It is mandatory reading for all fans of The Wire and recommended for everyone else.