Category: Economics

The $20 bill gets picked up, body parts markets in everything

At the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon Bonaparte’s final battle, more than 10,000 men and as many horses were killed in a single day. Yet today, archaeologists often struggle to find physical evidence of the dead from that bloody time period. Plowing and construction are usually the culprits behind missing historical remains, but they can’t explain the loss here. How did so many bones up and vanish?

In a new book, an international team of historians and archaeologists argues the bones were depleted by industrial-scale grave robbing. The introduction of phosphates for fertilizer and bone char as an ingredient in beet sugar processing at the beginning of the 19th century transformed bones into a hot commodity. Skyrocketing prices prompted raids on mass graves across Europe—and beyond.

Here is the full article, via William Meller. And, as Alex has stressed in the past, never underestimate the elasticity of supply!

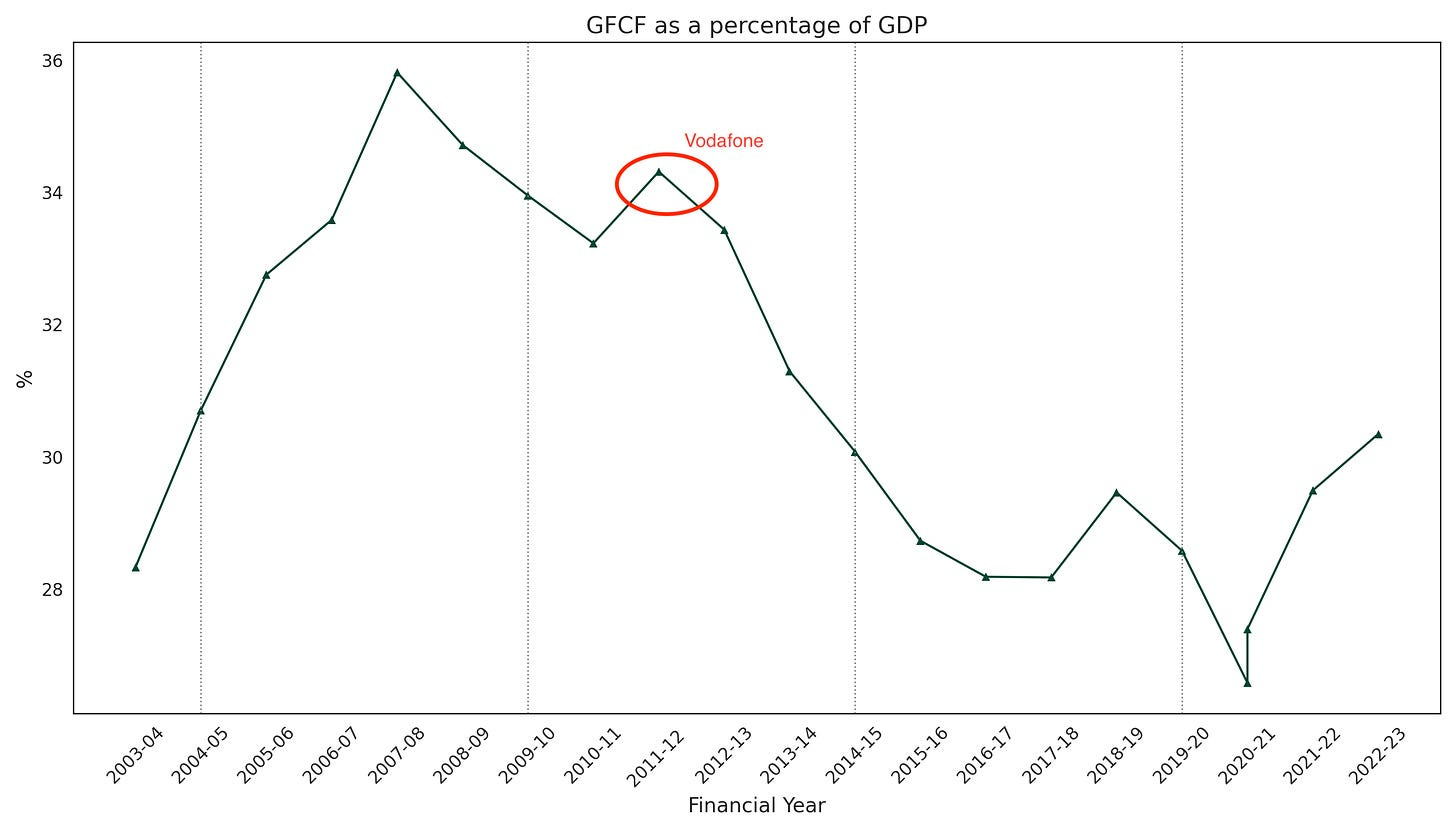

Modi and investment

Yes, India is doing well but the picture could be much better:

During Modi’s tenure, GFCF [gross fixed capital formation] as a percentage of GDP declined and has remained low until the post-pandemic recovery. In fact the highest level of GFCF as a percentage of GDP during the first nine years of Modi’s leadership is lower than the lowest level in PM Singh’s tenure.

Here is more from Shruti.

Philipp Strack wins the J.B. Clark award

Congratulations! Here is the AEA announcement and summary of his work.

Cultivating Minds: The Psychological Consequences of Rice versus Wheat Farming

It’s long been argued that the means of production influence social, cultural and psychological processes. Rice farming, for example, requires complex irrigation systems under communal management and intense, coordinated labor. Thus, it has been argued that successful rice farming communities tend to develop people with collectivist orientations, and cultural ways of thinking that emphasize group harmony and interdependence. In contrast, wheat farming, which requires less labor and coordination is associated with more individualistic cultures that value independence and personal autonomy. Implicit in Turner’s Frontier hypothesis, for example, is the idea that not only could a young man say ‘take this job and shove it’ and go west but once there they could establish a small, viable wheat farm (or other dry crop).

There is plenty of evidence for these theories. Rice cultures around the world do tend to exhibit similar cultural characteristics, including less focus on self, more relational or holistic thinking and greater in-group favoritism than wheat cultures. Similar differences exist between the rice and dry crop areas of China. The differences exist but is the explanation rice and wheat farming or are there are other genetic, historical or random factors at play?

A new paper by Talhelm and Dong in Nature Communications uses the craziness of China’s Cultural Revolution to provide causal evidence in favor of the rice and wheat farming theory of culture. After World War II ended, the communist government in China turned soldiers into farmers arbitrarily assigning them to newly created farms around the country–including two farms in Northern Ningxia province that were nearly identical in temperature, rainfall and acreage but one of the firms lay slightly above the river and one slightly below the river making the latter more suitable for rice farming and the former for wheat. During the Cultural Revolution, youth were shipped off to the farms “with very little preparation or forethought”. Thus, the two farms ended up in similar environments with similar people but different modes of production.

Talhelm and Dong measure thought style with a variety of simple experiments which have been shown in earlier work to be associated with collectivist and individualist thinking. When asked to draw circles representing themselves and friends or family, for example, people tend to self-inflate their own circle but they self-inflate more in individualist cultures.

Talhelm and Dong measure thought style with a variety of simple experiments which have been shown in earlier work to be associated with collectivist and individualist thinking. When asked to draw circles representing themselves and friends or family, for example, people tend to self-inflate their own circle but they self-inflate more in individualist cultures.

The authors find that consistent with the differences across East and West and across rice and wheat areas in China, the people on the rice farm in Ningxia are more collectivistic in their thinking than the people on the wheat farm.

The differences are all in the same direction but somewhat moderated suggesting that the effects can be created quite quickly (a few generations) but become stronger the longer and more embedded they are in the wider culture.

I am reminded of an another great paper, this one by Leibbrandt, Gneezy, and List (LGL) that I wrote about in Learning to Compete and Cooperate. LGL look at two types of fishing villages in Brazil. The villages are close to one another but some of them are on the lake and some of them are on the sea coast. Lake fishing is individualistic but sea fishing requires a collective effort. LGL find that the lake fishermen are much more willing to engage in competition–perhaps having seen that individual effort pays off–than the sea fishermen for whom individual effort is much less efficacious. Unlike Talhelm and Dong, LGL don’t have random assignment, although I see no reason why the lake and sea fishermen should otherwise be different, but they do find that women, who neither lake nor sea fish, do not show the same differences. Thus, the differences seem to be tied quite closely to production learning rather than to broader culture.

How long does it take to imprint these styles of thinking? How long does it last? Is imprinting during child or young adulthood more effective than later imprinting? Can one find the same sorts of differences between athletes of different sports–e.g. rowing versus running? It’s telling, for example, that the only famous rowers I can think are the Winklevoss twins. Are attempts to inculcate these types of thinking successful on a more than surface level. I have difficulty believing that “you didn’t build that,” changes say relational versus holistic thinking but would styles of thinking change during a war?

350+ coauthors study reproducibility in economics

Jon Hartley is one I know, here is the abstract:

This study pushes our understanding of research reliability by reproducing and replicating claims from 110 papers in leading economic and political science journals. The analysis involves computational reproducibility checks and robustness assessments. It reveals several patterns. First, we uncover a high rate of fully computationally reproducible results (over 85%). Second, excluding minor issues like missing packages or broken pathways, we uncover coding errors for about 25% of studies, with some studies containing multiple errors. Third, we test the robustness of the results to 5,511 re-analyses. We find a robustness reproducibility of about 70%. Robustness reproducibility rates are relatively higher for re-analyses that introduce new data and lower for re-analyses that change the sample or the definition of the dependent variable. Fourth, 52% of re-analysis effect size estimates are smaller than the original published estimates and the average statistical significance of a re-analysis is 77% of the original. Lastly, we rely on six teams of researchers working independently to answer eight additional research questions on the determinants of robustness reproducibility. Most teams find a negative relationship between replicators’ experience and reproducibility, while finding no relationship between reproducibility and the provision of intermediate or even raw data combined with the necessary cleaning codes.

Here is the full paper, here are some Twitter images. I have added the emphasis on the last sentence.

Economists do it with models?

Collaborations in economics across genders increased (12.5% increase of women coauthors per 100 men-authored papers) after #MeToo .

But senior researchers reduced their new collaborations with junior women by 33% per 100 senior-authored papers. https://t.co/zIxDF2Hukx pic.twitter.com/2YplnMTFoy

— Florian Ederer (@florianederer) April 7, 2024

A simple model of AI and social media

One MR reader, Luca Piron, writes to me:

I found myself puzzled by a thought you expressed during your interview with Professor Haidt. In particular, from my understanding you suggested that in the near future AI will be able to sum up the content a user may want to see into a digest, so that they can spend less time using their devices.

I think that is a misunderstanding of how the typical user experiences social media. While there surely are some brilliant people such as the young scientists you described during the episode who use social media only to connect with peers and find valuable information, I would argue that most users, alas including myself, turn to social media when seeking mindless distraction, when bored or maybe too tired to read of watch a film. Therefore, having a digest will prove unsatisfactory. What a typical user wants is the stream of content to continue.

I think these are some of the least understood points of 2024. Let us start with the substitution effect. The “digest” feature of AI will soon let you turn your feeds into summaries and pointers to the important parts. In other words, you will be able to consume those feeds more quickly. In some cases the quality of the feed experience may go up, in other cases it may go down (presumably over time quality of the digest will improve).

We all know that if tech allows you to cook more quickly (e.g., microwave ovens), you will spend less time cooking. That is true even if you are “addicted” to cooking, if you cook because of social pressures, if cooking puts you into a daze, or whatever. The substitution effect still applies, noting that in some cases the new tech may make the cooked food better, in other cases worse. In similar fashion, you will spend less time with your feed, following the advent of AI feed digests.

Somehow people do not want to acknowledge the price theory aspect of the problem, as they are content to repeat the motives of young people in spending time with their feeds. (You will note there is the possibility of a broader portfolio effect — AI might liberate you from many tasks, and you could end up spending more time with your feed. I’ll just say don’t bet against the substitution effect, it almost always dominates! And yes for addictive goods too. In fact those demand curves usually don’t look any different.) No one has to be a young genius scientist for the substitution effect to hold.

Note that a majority of U.S. teens report they spend about the right amount of time on social media apps (8% say “too little time”) and they are going to respond to technological changes with pretty normal kinds of behavior.

I think what has in fact happened is that commentators have read dozens of MSM articles about “algorithms,” and mostly are not following very recent tech developments, including in the consumer AI field. Perhaps that is why they have difficult processing what is a simple, straightforward argument, based on a first-order effect.

Another general way of putting the point, not as simple as a demand curve but still pretty straightforward, is that if tech creates a social problem, other forms of tech will be innovated and mobilized to help address that problem. Again, that is not a framing you get very often from MSM.

The AI example is also a forcing one when it comes to motives for spending time with social media feeds. Many critics wish to have it both ways. They want to say “the feed is no fun, teenagers stick with the feed because of social pressures to be in touch with others, but they ideally would rather do something else.” But when a new technology allows them to secede from feed obsession to some degree, (some of) those same critics say: “They can’t/won’t secede — they are addicted!” The word “dopamine” is then likely to follow, though rarely the word “fun.”

It is better to just start by admitting that the feed is fun, and informative, for many teenagers and adults too. Of course not everything fun is good for you, but the “social pressure” verbal gambit is a slight of hand to make social media sound like an obvious bad across all margins, and a network that needs to be taken down, rather than something we ought to help people manage better, at the margin. If it really were mainly a social pressure problem, it would be relatively easy to solve.

For many teens, both motives operate, namely scrolling the feed is fun, and there are social pressures to stay informed. The advent of the AI digest will allow those same individuals to cut back on the social pressure obligations, but keep the fun scrolling. Again, a substitution effect will operate, and furthermore it will nudge individuals away from the harmful social pressures and closer to the fun.

As Katherine Boyle pointed out on Twitter, a lot of this debate is being conducted in terms of 2016 technology. But in fact we are in 2024, not far from the summer of 2024, and soon to enter 2025. Beware of regulatory proposals, and social welfare analyses, that do not acknowledge that fact.

In the meantime, please do heed the substitution effect.

Your Subsidies are Undercutting My Subsidies!

NYTimes: Treasury officials say that they fear that elevated Chinese production targets are causing its firms to produce far more electric vehicles, batteries and solar panels than global markets can absorb, driving prices lower and disrupting production around the world. They fear that these spillovers will hurt businesses that are planning investments in the United States with tax credits and subsidies that were created through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, a law that is pumping more than $2 trillion into clean energy infrastructure.

Amazing that Yellen can say this with a straight face:

as an economist, it was her view that China could benefit if it stopped giving subsidies to firms that would fail without government support.

What should I ask Joe Stiglitz?

I will be having a Conversation with him, and please note this is the conversation I want to have, not the one you want me to have. So what should I ask? Note that Joe has a new book coming out The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society. That said, I also would like for the dialogue to cover Joe’s career more generally, starting with 1970 or so.

So what should I ask him?

Lockean homesteading for goats, bonus added

The mayor of an Italian island is attempting to solve an animal overpopulation problem with an unusual offer: free goats for anyone who can catch them.

Riccardo Gullo, the mayor of Alicudi, in Sicily’s Aeolian archipelago, introduced an “adopt-a-goat” program when the small island’s wild goat population grew to six times the human population of about 100.

Gullo said anyone who emails a request to the local government and pays a $17 “stamp fee” can take as many goats as they wish, as long as they transport them off the island within 15 days of approval.

“Anyone can make a request for a goat, it doesn’t have to be a farmer, and there are no restrictions on numbers,” he told The Guardian.

He said the scheme is currently available until April 10, but he will extend the deadline until the goat population is back down to a more manageable number.

The mayor told CNN that officials will not investigate the intentions of prospective goat owners, but “ideally, we would like to see people try to domesticate the animals rather than eat them.”

Here is the full story, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Algorithmic Collusion by Large Language Models

The rise of algorithmic pricing raises concerns of algorithmic collusion. We conduct experiments with algorithmic pricing agents based on Large Language Models (LLMs), and specifically GPT-4. We find that (1) LLM-based agents are adept at pricing tasks, (2) LLM-based pricing agents autonomously collude in oligopoly settings to the detriment of consumers, and (3) variation in seemingly innocuous phrases in LLM instructions (“prompts”) may increase collusion. These results extend to auction settings. Our findings underscore the need for antitrust regulation regarding algorithmic pricing, and uncover regulatory challenges unique to LLM-based pricing agents.

That is a new paper by Sara Fish, Yannai A. Gonczarowski, and Ran I. Shorrer. The authors are running too quickly into their policy conclusion there (how about removing legal barriers to free entry in many cases? not worth a mention?), but nonetheless very interesting work. Via Ethan Mollick.

Generative AI for economists

From Anton Korinek here is a recent paper:

Generative AI, in particular large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, has the potential to revolutionize research. I describe dozens of use cases along six domains in which LLMs are starting to become useful as both research assistants and tutors: ideation and feedback, writing, background research, data analysis, coding, and mathematical derivations. I provide general instructions and demonstrate specific examples of how to take advantage of each of these, classifying the LLM capabilities from experimental to highly useful. I argue that economists can reap significant productivity gains by taking advantage of generative AI to automate micro tasks. Moreover, these gains will grow as the performance of AI systems across all of these domains will continue to improve. I also speculate on the longer-term implications of AI-powered cognitive automation for economic research. The online resources associated with this paper offer instructions for how to get started and will provide regular updates on the latest capabilities of generative AI that are useful for economists.

Here is the home page for Korinek. Here is related applied work from Benjamin Manning. Economic research methods are changing right before our eyes, and most of the profession is asleep on this one.

Michael C. Jensen, RIP

Not only was he a major figure in both financial economics and industrial organization, but he did things too:

First, early on Mike decided that the Journal of Finance needed competition to drag it into the era of scientific research. Despite a chockful personal research agenda, Mike started the Journal of Financial Economics that he edited for 20+ years. After its 1974 debut, the JFE quickly became the top journal in finance, and it had the desired effect of upping the game of the JF.

Second, Mike’s foresight was unmatched. With the arrival of the internet, he predicted it would become the conduit for the distribution of new research. He launched SSRN (Social Science Research Network), supported it financially, and guided it for many years, never doubting it would succeed. His unfailing faith was eventually vindicated.

Here is the full tribute from Gene Fama.

LLMs vs. ARMA-GARCH

The LLMs basically win:

This paper presents a novel study on harnessing Large Language Models’ (LLMs) outstanding knowledge and reasoning abilities for explainable financial time series forecasting. The application of machine learning models to financial time series comes with several challenges, including the difficulty in cross-sequence reasoning and inference, the hurdle of incorporating multi-modal signals from historical news, financial knowledge graphs, etc., and the issue of interpreting and explaining the model results. In this paper, we focus on NASDAQ-100 stocks, making use of publicly accessible historical stock price data, company metadata, and historical economic/financial news. We conduct experiments to illustrate the potential of LLMs in offering a unified solution to the aforementioned challenges. Our experiments include trying zero-shot/fewshot inference with GPT-4 and instruction-based fine-tuning with a public LLM model Open LLaMA. We demonstrate our approach outperforms a few baselines, including the widely applied classic ARMA-GARCH model and a gradient-boosting tree model. Through the performance comparison results and a few examples, we find LLMs can make a well-thought decision by reasoning over information from both textual news and price time series and extracting insights, leveraging cross-sequence information, and utilizing the inherent knowledge embedded within the LLM. Additionally, we show that a publicly available LLM such as Open-LLaMA, after fine-tuning, can comprehend the instruction to generate explainable forecasts and achieve reasonable performance, albeit relatively inferior in comparison to GPT-4.

This kind of work is in its infancy of course. Nonetheless these are intriguing results, here is the paper. Via an MR reader.

Why aren’t Canada and other Anglo nations turning against immigration more?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column. I cover several points, here is one of them, based on the economic idea of intertemporal substitution:

In this sense, Canada is ahead of much of the rest of the world in seeing the importance of these factors and turning it into actionable policy. It is willing to give up some of its present cultural identity to achieve a brighter cultural and political future.

This trade-off is much better than it looks at first. For one thing, birth rates for native-born citizens may fall further than they have already. If a country wants to preserve its national culture, it may be better off allowing more migration now, when there is still a critical mass of native-born citizens to ease assimilation.

To put the point more generally: Whatever costs there might be to immigration, successful nations will have to deal with them sooner or later. And the sooner they do, the better off they will be. The choice is not so much between more immigration and less immigration, but rather a lot of immigration now or a lot later. This choice will become all the more pressing as the need to fund national retirement programs requires more tax-paying citizens.

And on real estate prices:

One of the most common criticisms of immigrants is that they push up real estate prices. Yet there is a home-grown explanation: Stringent regulations on building make it difficult for the supply of housing to respond when demand increases.

In fact, there is a way immigration can help address this problem. First, immigrants may themselves induce their adopted country to free up its real estate markets. So immigration might increase real estate costs in the short run, but help reduce them in the longer run. Second, immigrants can help lower-tier cities move to the fore. The suburbs of Toronto, for example, have seen much of their growth driven by Asian in-migration, and longer term that will give Canadians more residential (and commercial) options.

These points aside, note that higher real estate prices, to the extent they result from immigrant demands, largely translate into capital gains for homeowners — most of whom are native-born. To be sure, the higher home prices may be bad for many younger Canadians, who may be locked out of housing markets, but eventually many of them will inherit high-valued homes from their parents.

Rrecommended.