Results for “Brynjolfsson” 37 found

Erik Brynjolfsson interviews Daniel Kahneman

Mostly about AI, here is one bit:

My guess is that AI is very, very good at decoding human interactions and human expressions. If you imagine a robot that sees you at home, and sees your interaction with your spouse, and sees things over time; that robot will be learning. But what robots learn is learned by all, like self-driving cars. It’s not the experience of the single, individual self-driving car. So, the accumulation of emotional intelligence will be very rapid once we start to have that kind of robot .

It’s really interesting to think about whether people are happier now than they were. This is not at all obvious because people adapt and habituate to most of what they have. So, the question to consider about well-being and about providing various goods to people, is whether they’re going to get used to having those goods, and whether they continue to enjoy those goods. It’s not apparent how valuable these things are, and it will be interesting to see how this changes in the future.

Kahneman tells us that his forthcoming book is called Noise, though I don’t yet find it on Amazon. Here is an HBR essay of his on that topic.

Generative AI at Work

We study the staggered introduction of a generative AI-based conversational assistant using data from 5,179 customer support agents. Access to the tool increases productivity, as measured by issues resolved per hour, by 14 percent on average, with the greatest impact on novice and low-skilled workers, and minimal impact on experienced and highly skilled workers. We provide suggestive evidence that the AI model disseminates the potentially tacit knowledge of more able workers and helps newer workers move down the experience curve. In addition, we show that AI assistance improves customer sentiment, reduces requests for managerial intervention, and improves employee retention.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, and Lindsey R. Raymond.

The case for a market allocation of vaccines

Or a partial such allocation, at least. Here is my latest Bloomberg column:

The renowned economist Erik Brynjolfsson recently asked: “At least so far, I haven’t seen any one suggesting to use the market system to allocate vaccines. Not even those who strongly advocate it in other areas. Why is that?”

As one of several people copied at the bottom of the tweet, I feel compelled to take up the challenge.

I readily admit that a significant portion of the vaccines, when they come, should be allocated by non-market forces to health care workers, “front line” workers, servicemen on aircraft carriers, and so on. Yet still there is room for market allocation, especially since multiple vaccines are a real possibility:

If you had to choose among those vaccines, wouldn’t it make sense to look for guidance from market prices? They will reflect information about the perceived value of both protection and risk. On the same principle, if you need brain surgery, you would certainly want to know what the brain surgeon charges, although of course that should not be the only factor in your decision.

And:

The market prices for vaccines could be useful for other purposes as well. If scientific resources need to be allocated to improve vaccines or particular vaccine approaches, for instance, market prices might be useful signals.

Note also that the scope of the market might expand over time. In the early days of vaccine distribution, health-care workers will be a priority. Eventually, however, most of them will have access to vaccines. Selling off remaining vaccine doses might do more to encourage additional production than would bureaucratic allocation at a lower price.

Say China gets a vaccine first — how about a vaccine vacation in a nearby Asian locale (Singapore? Vietnam?) for 30k? Unless you think that should be illegal, you favor some form of a market in vaccines.

In any case, there is much more at the link. Overall I found it striking how few people took up Erik’s challenge. Whether or not you agree with my arguments, to me they do not seem like such a stretch.

Nuclear Energy Saves Lives

Germany’s closing of nuclear power stations after Fukishima cost billions of dollars and killed thousands of people due to more air pollution. Here’s Stephen Jarvis, Olivier Deschenes and Akshaya Jha on The Private and External Costs of Germany’s Nuclear Phase-Out:

Following the Fukashima disaster in 2011, German authorities made the unprecedented decision to: (1) immediately shut down almost half of the country’s nuclear power plants and (2) shut down all of the remaining nuclear power plants by 2022. We quantify the full extent of the economic and environmental costs of this decision. Our analysis indicates that the phase-out of nuclear power comes with an annual cost to Germany of roughly$12 billion per year. Over 70% of this cost is due to the 1,100 excess deaths per year resulting from the local air pollution emitted by the coal-fired power plants operating in place of the shutdown nuclear plants. Our estimated costs of the nuclear phase-out far exceed the right-tail estimates of the benefits from the phase-out due to reductions in nuclear accident risk and waste disposal costs.

Moreover, we find that the phase-out resulted in substantial increases in the electricity prices paid by consumers. One might thus expect German citizens to strongly oppose the phase-out policy both because of the air pollution costs and increases in electricity prices imposed upon them as a result of the policy. On the contrary, the nuclear phase-out still has widespread support, with more than 81% in favor of it in a 2015 survey.

If even the Germans are against nuclear and are also turning against wind power the options for dealing with climate change are shrinking.

Hat tip: Erik Brynjolfsson.

Are we undermeasuring productivity gains from the internet? part I

From my new paper with Ben Southwood on whether the rate of scientific progress is slowing down:

Third, we shouldn’t expect mismeasured GDP simply from the fact that the internet makes many goods and services cheaper. Spotify provides access to a huge range of music, and very cheaply, such that consumers can listen in a year to albums that would have cost them tens of thousands of dollars in the CD or vinyl eras. Yet this won’t lead to mismeasured GDP. For one thing, the gdp deflator already tries to capture these effects. But even if those efforts are imperfect, consider the broader economic interrelations. To the extent consumers save money on music, they have more to spend or invest elsewhere, and those alternative choices will indeed be captured by GDP. Another alternative (which does not seem to hold for music) is that the lower prices will increase the total amount of money spent on recorded music, which would mean a boost in recorded GDP for the music sector alone. Yet another alternative, more plausible, is that many artists give away their music on Spotify and YouTube to boost the demand for their live performances, and the increase in GDP shows up there. No matter how you slice the cake, cheaper goods and services should not in general lower measured GDP in a way that will generate significant mismeasurement.

Moving to the more formal studies, the Federal Reserve’s David Byrne, with Fed & IMF colleagues, finds a productivity adjustment worth only a few basis points when attempting to account for the gains from cheaper internet age and internet-enabled products. Work by Erik Brynjolfsson and Joo Hee Oh studies the allocation of time, and finds that people are valuing free Internet services at about $106 billion a year. That’s well under one percent of GDP, and it is not nearly large enough to close the measured productivity gap. A study by Nakamura, Samuels, and Soloveichik measures the value of free media on the internet, and concludes it is a small fraction of GDP, for instance 0.005% of measured nominal GDP growth between 1998 and 2012.

Economist Chad Syverson probably has done the most to deflate the idea of major unmeasured productivity gains through internet technologies. For instance, countries with much smaller tech sectors than the United States usually have had comparably sized productivity slowdowns. That suggests the problem is quite general, and not belied by unmeasured productivity gains. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the productivity slowdown is quite large in scale, compared to the size of the tech sector. Using a conservative estimate, the productivity slowdown implies a cumulative loss of $2.7 trillion in GDP since the end of 2004; in other words, output would have been that much higher had the earlier rate of productivity growth been maintained. If unmeasured gains are to make up for that difference, that would have to be very large. For instance, consumer surplus would have to be five times higher in IT-related sectors than elsewhere in the economy, which seems implausibly large.

You can find footnotes and references in the original. Here is my earlier post on the paper.

Saturday assorted links

1. Human corpses keep moving for a year after death.

2. Scarce labor and low interest rates. By Benzell and Brynjolfsson.

3. My Stubborn Attachments philosophy podcast, Elucidations, with Matt Teichman.

4. Are we living in the most influential time ever?

5. Average is Over: “These synthetic husbands have an average income that is about 58% higher than the actual unmarried men that are currently available to unmarried women.”

6. Thomas Piketty slides based on his forthcoming book; the word “Mormon” does not appear.

The value of Facebook and other digital services

Women seem to value Facebook more than men do.

Older consumers value Facebook more.

Education and US region do not seem to be significant.

The median compensation for giving up Facebook is in the range of $40 to $50 a month, based mostly on surveys, though some people do actually have to give up Facebook.

I find it hard to believe the survey-based estimate that search engines are worth over 17k a year.

Email is worth 8.4k, and digital maps 3.6k, and video streaming at 1.1k, again all at the median and based on surveys. Personally, I value digital maps at close to zero, mostly because I do not know how to use them.

That is all from a new NBER paper by Erik Brynjolfsson, Felix Eggers, and Avinash Gannamaneni.

How economists use Twitter

When using Twitter, both economists and natural scientists communicate mostly with people outside their profession, but economists tweet less, mention fewer people and have fewer conversations with strangers than a comparable group of experts in the sciences. That is the central finding of research by Marina Della Giusta and colleagues, to be presented at the Royal Economic Society’s annual conference at the University of Sussex in Brighton in March 2018.

Their study also finds that economists use less accessible language with words that are more complex and more abbreviations. What’s more, their tone is more distant, less personal and less inclusive than that used by scientists.

The researchers reached these conclusions gathering data on tens of thousands of tweets from the Twitter accounts of both the top 25 economists and 25 scientists as identified by IDEAS and sciencemag. The top three economists are Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz and Erik Brynjolfsson; the top three scientists are Neil deGrasse Tyson, Brian Cox and Richard Dawkins.

Here is further information, via Romesh Vaitilingam. But I cannot find the original research paper on-line. These are interesting results, but still I would like to see the shape of the entire distribution…

The Economics of Attention

David Evans on the economics of attention:

In 2016, 437 billion hours, worth $7.1 trillion dollars, were exchanged in the

attention market in the US based on conservative estimates reported above. Attention

platforms paid for that time with content and then sold advertisers access to portions of that

time. As a result, advertisers were able to deliver messages to consumers that those

consumers would probably not have accepted in the absence of the barter of content for

their time. Consumers often don’t like getting these messages. But by agreeing to receive

them they make markets more competitive.

The economics of attention markets focuses on three features. First it focuses on

time as the key dimension of competition since it is what is being bought and sold. Second,

it focuses on content since it plays a central role in acquiring time, embedding advertising

messages, and operating efficient attention platforms. And third it focuses on the scarcity of

time and the implications of that for competition among attention platforms.

The $7.1 trillion estimate for the value of content seems too high. The high value comes from Evans assuming that the marginal wage is higher than the average so the average wage which he uses to calculate the value of time is, if anything, an underestimate while for most people I think the marginal wage is lower than the average (many people don’t even have jobs) so the average is an over-estimate. Brynjolfsson and Oh, however, using somewhat different methods estimate the consumer surplus from television as 10% of GDP and from the internet of 6% GDP or combined about $3 trillion at current levels. Either way the attention economy is very large and understudied relative to its importance.

*Machine Platform Crowd*

The authors are Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, and the subtitle is Harnessing Our Digital Future. Arguably McAfee and Brynjolfsson have become America’s leading authors of business/management books (with an economic slant). This one is due out June 27, I am eager to read it.

Toward a theory of Marginal Revolution, the blog

I found this pretty awesome and flattering (I couldn’t manage to indent it or get the formatting right):

Exploring the Marginal Revolution Dataset, by Will Nowak

1 Sept 2016

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Housekeeping

- 3 Exploratory Data Analysis

- 4 Comparative Plots

- 4.1 Hypothesis 1: Are posts getting longer (or shorter) over time?

- 4.2 Hypothesis 2: Do longer posts indicate more (or less) comments?

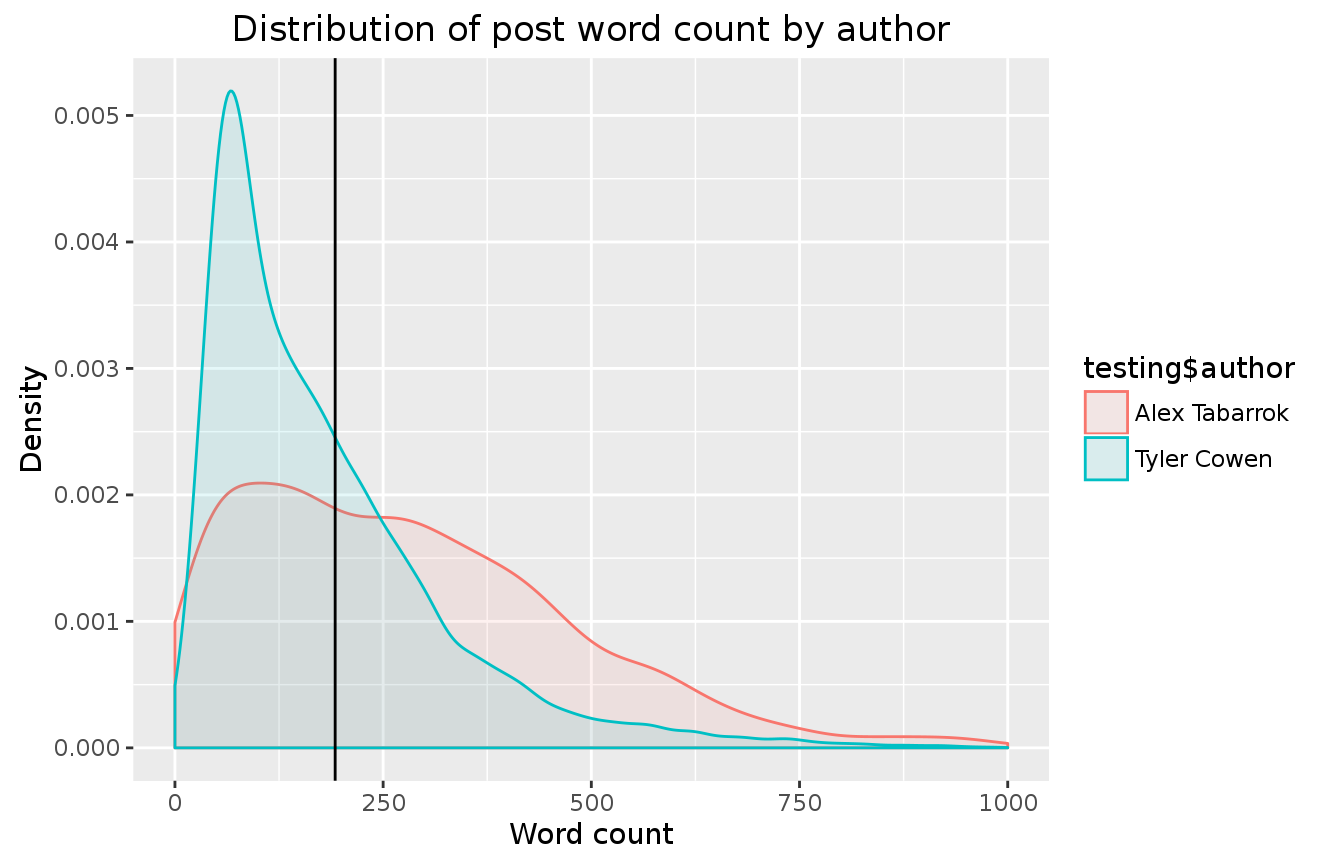

- 4.3 Hypothesis 3: Cowen contributes more often, but Tabbarok often has long posts. Does the data confirm?

- 4.4 Hypothesis 4: Cowen receives more comments, as he blogs more often and has more of a following:

- 5 Machine Learning

Once again, here is the link. There are excellent visuals and histograms, the programming is there too, and again that is from Will Nowak. And here is an updated version of blog content.

Anthony Goldbloom pointed me to this, and is involved in the larger project, and I thank also Erik Brynjolfsson for an introduction.

The Logic of Closed Borders

Bloomberg: At least 100 workers at the construction site for Tesla Motors Inc.’s battery factory near Reno, Nevada, walked off the job Monday to protest use of workers from other states, a union official said.

Local labor leaders are upset that Tesla contractor Brycon Corp. is bringing in workers from Arizona and New Mexico, said Todd Koch, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Northern Nevada.

“It’s a slap in the face to Nevada workers to walk through the parking lot at the job site and see all these license plates from Arizona and New Mexico,” Koch said in an interview. Those who walked out were among the hundreds on the site, he said.

Erik Brynjolfsson tweeted “Build a wall! And make New Mexico pay for it.” Or perhaps require that Nevada carpenters be licensed.

China fact of the day

WeChat had more mobile transactions over just Chinese New Year than PayPal had during 2015…

According to WeChat, owned by digital media business Tencent, 420 million people sent each other lucky money via the app’s payment service on the eve of Chinese New Year. According to WeChat, it has seen a total of 8.08 billion red envelopes sent so far for Chinese New Year, eight times more than last year.

To put this into context, according to PayPal it made 4.9 billion transactions in 2015 (half of the number of transactions made on WeChat just for Chinese New Year) and only 28 per cent were made on a mobile device.

Here is the article, hat tip goes to Erik Brynjolfsson. Do not underestimate the potential for Chinese innovation in information technology!

Why Does Ursula K. Le Guin Hate Amazon?

Ursula K. Le Guin’s poorly-argued and evidence-free rant against Amazon is more about her hatred of capitalism than about Amazon’s actual effect on the market for books. Here’s Le Guin:

[Amazon’s] ideal book is a safe commodity, a commercial product written to the specifications of the current market, that will hit the BS list, get to the top, and vanish. Sell it fast, sell it cheap, dump it, sell the next thing. No book has value in itself, only as it makes profit. Quick obsolescence, disposability — the creation of trash — is an essential element of the BS machine. Amazon exploits the cycle of instant satisfaction/endless dissatisfaction. Every book purchase made from Amazon is a vote for a culture without content and without contentment.

The same argument was made in the late 1990s against chain bookstores like Border’s. It wasn’t a good argument then (see Tyler’s masterpiece, In Praise of Commercial Culture) but at least at that time it was debatable. Le Guin’s attempt to resurrect the argument today is bizarre. Does anyone doubt that it is easier to buy a niche book today than it ever has been in the entire history of the world? Indeed, does anyone doubt that it is easier to buy a Ursula K. Le Guin book today than it ever has been in the entire history of the world?

Larger markets support greater variety. A bookstore that only sells locally can’t stock many books. It’s the smaller store that fears taking a risk because the opportunity cost of shelf space is so high. Amazon lowers the cost of stocking books through efficient logistics and by warehousing in relatively low-cost areas (subject to being close to markets). The fixed costs of distribution are then spread over a much larger (inter)-national market so it pays to stock many more books.

Amazon makes a lot of money selling niche books. The precise numbers are debatable because Amazon doesn’t release much data but Brynjolfsson, Hu and Smith estimated that the long-tail accounted for nearly 40% of Amazon sales in 2008, a number that had risen over time. Indeed, since costs aren’t that different it’s not obvious that Amazon makes much more from selling a million copies of a single book than from 10 copies of each of 100,000 books (especially if they are ebooks).

Ebooks take this argument to the limit and the data show greater diversity in who publishes books than ever before. According to a recent Author Earnings report:

…indie self-published authors and their ebooks were outearning all authors published by the Big Five publishers combined

Perhaps what pushes Le Guin onto the wrong track is that there are more (inter)-national blockbusters than ever before which gives some people the impression that variety is declining. It’s not a contradiction, however, that niche products can become more easily available even as there are more blockbusters–as Paul Krugman explained the two phenomena are part and parcel of the same logic of larger markets. It’s important, however, to keep one’s eye on the variety available to individuals. Variety has gone up for every person even as some measures of geographic variety have gone down.

In the past small sci-fi booksellers in out-of-the-way places (link to my youth) barely eked out a living from selling books. Precisely because they didn’t make a lot of money, however, the independents signaled their worthy devotion to the revered authors. Today, Amazon sells more Le Guin books than any independent ever did. But Bezos doesn’t revere Le Guin, he treats her books as a commodity. That may distress Le Guin but for readers, book capitalism is a wonder, books and books and books available on our devices within seconds, more books than we could ever read; a veritable fountain, no a firehose, no an Amazon of books.

Are S&P 500 firms now 5/6 “dark matter” or intangibles?

Justin Fox started it, and Robin Hanson has a good restatement of the puzzle:

The S&P 500 are five hundred big public firms listed on US exchanges. Imagine that you wanted to create a new firm to compete with one of these big established firms. So you wanted to duplicate that firm’s products, employees, buildings, machines, land, trucks, etc. You’d hire away some key employees and copy their business process, at least as much as you could see and were legally allowed to copy.

Forty years ago the cost to copy such a firm was about 5/6 of the total stock price of that firm. So 1/6 of that stock price represented the value of things you couldn’t easily copy, like patents, customer goodwill, employee goodwill, regulator favoritism, and hard to see features of company methods and culture. Today it costs only 1/6 of the stock price to copy all a firm’s visible items and features that you can legally copy. So today the other 5/6 of the stock price represents the value of all those things you can’t copy.

Check out his list of hypotheses. Scott Sumner reports:

Here are three reasons that others have pointed to:

1. The growing importance of rents in residential real estate.

2. The vast upsurge in the share of corporate assets that are “intangible.”

3. The huge growth in the complexity of regulation, which favors large firms.

It’s easy enough to see how this discrepancy may have evolved for the tech sector, but for the Starbucks sector of the economy I don’t quite get it. A big boost in monopoly power can create a larger measured role for accounting intangibles, but Starbucks has plenty of competition, just ask Alex. Our biggest monopoly problems are schools and hospitals, which do not play a significant role in the S&P 500.

Another hypothesis — not cited by Sumner or Hanson — is that the difference between book and market value of firms is diverging over time. That increasing residual gets classified as an intangible, but we are underestimating the value of traditional physical capital, and by more as time passes.

Cowen’s second law (“There is a literature on everything”) now enters, and leads us to Beaver and Ryan (pdf), who study biases in book to market value. Accounting conservatism, historical cost, expected positive value projects, and inflation all can contribute to a widening gap between book and market value. They also suggest (published 2000) that overestimations of the return to capital have bearish implications for future returns. It’s an interesting question when the measured and actual means for returns have to catch up with each other, what predictions this eventual catch-up implies, and whether those predictions have come true. How much of the growing gap is a “bias component” vs. a “lag component”? Heady stuff, the follow-up literature is here.

Perhaps most generally, there is Hulten and Hao (pdf):

We find that conventional book value alone explains only 31 percent of the market capitalization of these firms in 2006, and that this increases to 75 percent when our estimates of intangible capital are included.

So some of it really is intangibles, but a big part of the change still may be an accounting residual. Their paper has excellent examples and numbers, but note they focus on R&D intensive corporations, not all corporations, so their results address less of the entire problem than a quick glance might indicate. By the way, all this means the American economy (and others too?) has less leverage than the published numbers might otherwise indicate.

Here is a 552 pp. NBER book on all of these issues, I have not read it but it is on its way in the mail. Try also this Robert E. Hall piece (pdf), he notes a “capital catastrophe” occurred in the mid-1970s, furthermore he considers what rates of capital accumulation might be consistent with a high value for intangible assets. That piece of the puzzle has to fit together too. This excellent Baruch Lev paper (pdf) considers some of the accounting issues, and also how mismeasured intangible assets often end up having their value captured by insiders; that is a kind of rent-seeking explanation. See also his book Intangibles. Don’t forget the papers of Erik Brynjolfsson on intangibles in the tech world, if I recall correctly he shows that the cross-sectoral predictions line up more or less the way you would expect. Here is a splat of further references from scholar.google.com.

I would sum it up this way: measuring intangible values properly shows much of this change in the composition of American corporate assets has been real. But a significant gap remains, and accounting conventions, based on an increasing gap between book and market value, are a primary contender for explaining what is going on. In any case, there remain many underexplored angles to this puzzle.

Addendum: I wish to thank @pmarca for a useful Twitter conversation related to this topic.