Results for “Test prep” 185 found

The SAT, Test Prep, Income and Race

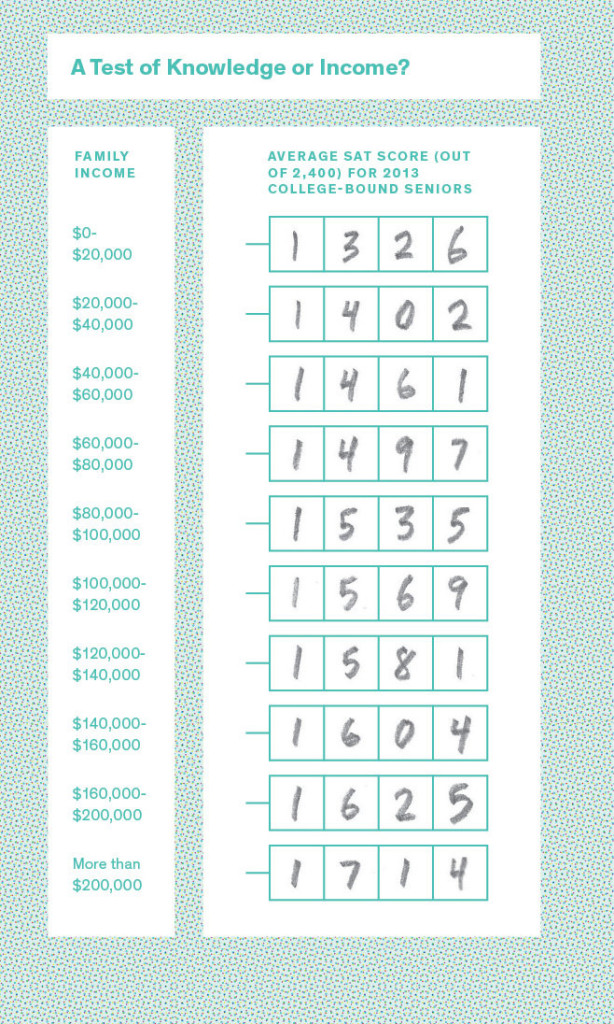

The announcement of the new, new SAT has created a lot of hand-wringing about SAT scores and their correlations with income and also race. Wonkblog, the New York Times and many others all feature a table or chart showing how SAT scores increase with income. Wonkblog says these charts “show how the SAT  favors rich, educated families,” and the NYTimes says about the SAT, “A Test of Knowledge or Income?” The consensus explanation for these “shocking” results is the evil of test prep as summarized by NBCNews:

favors rich, educated families,” and the NYTimes says about the SAT, “A Test of Knowledge or Income?” The consensus explanation for these “shocking” results is the evil of test prep as summarized by NBCNews:

…there is also mounting criticism as to whether students who can afford expensive SAT test preparation courses have an unfair advantage, especially given a strong correlation between family income level and test results.

Similarly, Chris Hayes blames test prep for inequality:

We’ve had…the growth of this tremendous testing and test prep industry in New York, along with the massive rise in inequality and it has produced a system in which the school is now admitting only three, four, five black and Latino students. The students they are admitting are almost entirely white, affluent kids with tutors or second generation, first generation immigrants from Queens and other places where the parents pay for test prep. You end up with a system where who you are really letting in are the kids with access to test prep, the kids with access to resources.

All of this is almost entirely at variance with three facts, all of which are well known among education researchers.

First, test prep has only a modest effect on test scores, on the order of 20-40 points combined for a commercial test preparation service. More expensive services such as a private tutor are towards the high of this range, cheaper sources such as a high-school course towards the lower. Buchmann et al., for example, estimate that private tutors increase scores by 37 points while a high school course increases scores by 26 points.

The average SAT score among those with a family income of $20,000-$40,000 is 1402 while the average score among those with an income $100,000 higher, $120,000-$140,000, is 1581 for a 179 point difference. Even if every rich family had a private tutor and none of the poor families had any test prep whatsoever, test prep would explain only 20% of the difference 37/179. If rich families rely on tutors and poor families rely on high school courses, the difference in test prep would explain only 6% (11/179) of the difference in score.

The second surprising fact about test prep is that it doesn’t vary nearly as much by income as people imagine. In fact, some studies find no effect of income on test prep use while others find a positive but modest effect. The latter study finding (what I call) a modest effect finds that in their sample a 2-standard deviation increase in income above the mean increases the probability of using a private test prep course less than whether “Parent encouraged student to prep for SAT (yes or no).”

Since test prep differs by income only modestly and since test prep increases scores only modestly, the effect of income on test scores through test prep is small, Modest*Modest=Small. Contrary to the consensus, test prep can in no way account for the large differences in SAT score by income.

The third fact is that test prep varies by race in the opposite way that people imagine. In the quote above, Chris Hayes suggests that whites use test prep much more than blacks. In fact, blacks use test prep more than whites, as is well documented among education researchers (e.g. here, here, here), e.g. from the first link:

…blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites from comparable backgrounds to utilize test preparation. The black-white gap is especially pronounced in the use of high school courses, private courses and private tutors.

Indeed, since blacks use test prep more than whites and blacks have lower SAT scores than whites the effect of test prep is to reduce not increase the black-white gap in scores. Of course, the net reduction in the gap is small.

Is Bach the greatest achiever of all time?

I’ve been reading and rereading biographies of Bach lately (for some podcast prep), and it strikes me he might count as the greatest achiever of all time. That is distinct from say regarding him as your favorite composer or artist of all time. I would include the following metrics as relevant for that designation:

1. Quality of work.

2. How much better he was than his contemporaries.

3. How much he stayed the very best in subsequent centuries.

4. Quantity of work.

5. Peaks.

6. Consistency of work and achievement.

7. How many other problems he had to solve to succeed with his achievement. For Bach, this might include a) finding musical manuscripts, b) finding organs good enough to play and compose on, c) dealing with various local and church authorities, d) migrating so successfully across jurisdictions, e) composing at an impossibly high level during the four years he was widowed (with kids), before remarrying.

8. Ending up so great that he could learn only from himself.

9. Never experiencing true defeat or setback (rules out Napoleon!).

I see Bach as ranking very, very high in all these categories. Who else might even be a contender for greatest achiever of all time? Shakespeare? Maybe, but Bach seems to beat him for relentlessness and quantity (at a very high quality level). Beethoven would be high on the list, but he doesn’t seem to quite match up to Bach in all of these categories. Homer seems relevant, but we are not even sure who or what he was. Archimedes? Plato or Aristotle? Who else?

Addendum: from Lucas, in the comments:

Is it Possible to Prepare for a Pandemic?

In a new paper, Robert Tucker Omberg and I ask whether being “prepared for a pandemic” ameliorated or shortened the pandemic. The short answer is No.

How effective were investments in pandemic preparation? We use a comprehensive and detailed measure of pandemic preparedness, the Global Health Security (GHS) Index produced by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU), to measure which investments in pandemic preparedness reduced infections, deaths, excess deaths, or otherwise ameliorated or shortened the pandemic. We also look at whether values or attitudinal factors such as individualism, willingness to sacrifice, or trust in government—which might be considered a form of cultural pandemic preparedness—influenced the course of the pandemic. Our primary finding is that almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic. Compared to other countries, the United States did not perform poorly because of cultural values such as individualism, collectivism, selfishness, or lack of trust. General state capacity, as opposed to specific pandemic investments, is one of the few factors which appears to improve pandemic performance. Understanding the most effective forms of pandemic preparedness can help guide future investments. Our results may also suggest that either we aren’t measuring what is important or that pandemic preparedness is a global public good.

Our results can be simply illustrated by looking at daily Covid deaths per million in the country the GHS Index ranked as the most prepared for a pandemic, the United States, versus the country the GHS Index ranked as least prepared, Equatorial Guinea.

Now, of course, this is just raw data–maybe the US had different demographics, maybe Equatorial Guinea underestimated Covid deaths, maybe the GHS index is too broad or maybe sub-indexes measured preparation better. The bulk of our paper shows that the lesson of Figure 1 continue to apply even after controlling for a variety of demographic factors, when looking at other measures of deaths such as excess deaths, when looking at the time pattern of deaths etc. Note also that we are testing whether “preparedness” mattered and finding that it wasn’t an important factor in the course of the pandemic. We are not testing and not arguing that pandemic policy didn’t matter.

The lessons are not entirely negative, however. The GHS index measures pandemic preparedness by country but what mattered most to the world was the production of vaccines which depended less on any given country and more on global preparedness. Investing in global public goods such as by creating a library of vaccine candidates in advance that we could draw upon in the event of a pandemic is likely to have very high value. Indeed, it’s possible to begin to test and advance to phase I and phase II trials vaccines for every virus that is likely to jump from animal to human populations (Krammer, 2020). I am also a big proponent of wastewater surveillance. Every major sewage plant in the world and many minor plants at places like universities ought to be doing wastewater surveillance for viruses and bacteria. The CDC has a good program along these lines. These types of investments are global public goods and so don’t show up much in pandemic preparedness indexes, but they are key to a) making vaccines available more quickly and b) identifying and stopping a pandemic quickly.

A final lesson may be that a pandemic is simply one example of a low-probability but very bad event. Other examples which may have even greater expected cost are super-volcanoes, asteroid strikes, nuclear wars, and solar storms (Ord, 2020; Leigh, 2021). Preparing for X, Y, or Z may be less valuable than building resilience for a wide variety of potential events. The Boy Scout motto is simply ‘Be prepared’.

Read the whole thing.

The FDA’s Lab-Test Power Grab

The FDA is trying to gain authority over laboratory developed tests (LDTs). It’s a bad idea. Writing in the WSJ, Brian Harrison, who served as chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019-2021 and Bob Charrow, who served as HHS general counsel, 2018-2021, write:

We both were involved in preparing the federal Covid-19 public-health emergency declaration. When it was signed on Jan. 31, 2020, the intent was to cut red tape and maximize regulatory flexibility to allow a nimble response to an emerging pandemic.

Unknown to us, the next day the FDA went in the opposite direction: It issued a new requirement that labs stop testing for Covid-19 and first apply for FDA authorization. At that time, LDTs were the only Covid tests the U.S. had, and many were available and ready to be used in labs around the country. But since the process for emergency-use authorization was extremely burdensome and slow—and because, as we and others in department leadership learned, it couldn’t process applications quickly—many labs stopped trying to win authorization, and some pleaded for regulatory relief so they could test.

Through this new requirement the FDA effectively outlawed all Covid-19 testing for the first month of the pandemic when detection was most critical. One test got through—the one developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—but it proved to be one of the highest-profile testing failures in history because the entire nation was relying on the test to work as designed, and it didn’t.

When we became aware of the FDA’s action, one of us (Mr. Harrison) demanded an immediate review of the agency’s legal authority to regulate these tests, and the other (Mr. Charrow) conducted the review. Based on the assessment, a determination was made by department leadership that the FDA shouldn’t be regulating LDTs.

Congress has never expressly given the FDA authority to regulate the tests. Further, in 1992 the secretary of health and human services issued a regulation stating that these tests fell under the jurisdiction of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, not the FDA. Bureaucrats at the FDA have tried to ignore this rule even though the Supreme Court in Berkovitz v. U.S. (1988) specifically admonished the agency for ignoring federal regulations.

Loyal readers will recall that I covered this issue earlier in Clement and Tribe Predicted the FDA Catastrophe. Clement, the former US Solicitor General under George W. Bush and Tribe, a leading liberal constitutional lawyer, rejected the FDA claims of regulatory authority over laboratory developed tests on historical, statutory, and legal grounds but they also argued that letting the FDA regulate laboratory tests was a dangerous idea. In a remarkably prescient passage, Clement and Tribe (2015, p. 18) warned:

The FDA approval process is protracted and not designed for the rapid clearance of tests. Many clinical laboratories track world trends regarding infectious diseases ranging from SARS to H1N1 and Avian Influenza. In these fast-moving, life-or-death situations, awaiting the development of manufactured test kits and the completion of FDA’s clearance procedures could entail potentially catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care.

Clement and Tribe nailed it. Catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care is exactly what happened. Thus, Harrison and Charrow are correct, giving the FDA power over laboratory derived tests has had and will have significant costs.

Let’s eliminate the Covid test entry requirement for the U.S.

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, you ought to be able to guess most of my arguments. Here is the very end:

I am not arguing for passivity in the face of danger. It is distressing that US policymakers do not seem interested in spending big for pandemic preparedness. America needs a new Operation Warp Speed for pan-coronavirus vaccines and nasal spray vaccines. It should be gathering more data on Covid and improving its system of clinical trials for anti-Covid remedies, among other measures.

I am simply saying that removing the Covid test for entry to the US would bring an end to one of the more egregious instances of “hygiene theater.” And it would send a signal that America is welcoming the world once again.

Recommended. And note that the most responsible European countries do not impose such tests.

Be Prepared! Sars-COV-3

The federal government was unprepared for the pandemic, despite multiple, loud and clear warnings. State and local governments were unprepared for vaccines, despite multiple, loud and clear warnings. The Capitol Police were unprepared for rioters, despite multiple, loud and clear warnings.

The record isn’t good but as a Queen’s Scout I persist. We now have multiple, loud and clear warnings that new variants of the SARS-COV II virus are more transmissible and thus much more dangerous. But we can do something. As wrote in The New Strain and the Need for Speed

One of the big virtues of mRNA vaccines is that much like switching a bottling plant from Sprite to 7-Up we could tweak the formula and produce a new vaccine using exactly the same manufacturing plants. Moreover, Marks and Hahn at the FDA have said that the FDA would not require new clinical trials for safety and efficacy just smaller, shorter trials for immune response (similarly we don’t do new large-scale clinical trials for every iteration of the flu vaccine.) Thus, if we needed it, we could modify mRNA vaccines (not other types) for a new variant in say 8-12 weeks.

Thus, let’s start doing much more sequencing to discover new strains–and also think about potential new strains–and start phase I and phase II trials of new vaccines. Florian Krammer suggested an even more ambitious plan to do the same thing for all potential pandemic viruses:

From each of the identified virus families, which should certainly include the Paramyxoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, and Coronaviridae families, a handful of representative strains with the highest pandemic potential should be selected for vaccine production. Up to 50–100 different viruses could be selected and this would broadly cover all phylogenies that may give rise to pandemic strains….It should be possible to choose candidates that are close to viruses that might emerge in the human population. The idea is that once viruses are selected, vaccines can be produced in different platforms and tested in phase 1 and phase 2 trials with some of the produced vaccine being stockpiled. This would likely cost 20–30 million US dollars per vaccine candidate resulting in a cost of 1–3 billion US dollars.

What I am suggesting is less ambitious–just do this for Sars-COV-3, 4, 5 and 6. But do it now!

Hat tip: Daniel Bier.

Broken Record Addendum: We should make better use of our limited vaccine supply by moving to First Doses First and/or fractional dosing and approve the AstraZeneca vaccine immediately and spend billions to increase the rate of vaccinations and to speed new vaccines (such as those from J&J and Novavax) to market.

FDA Allows Pooled Tests and a Call for Prizes

The FDA has announced they will no longer forbid pooled testing:

In order to preserve testing resources, many developers are interested in performing their testing using a technique of “pooling” samples. This technique allows a lab to mix several samples together in a “batch” or pooled sample and then test the pooled sample with a diagnostic test. For example, four samples may be tested together, using only the resources needed for a single test. If the pooled sample is negative, it can be deduced that all patients were negative. If the pooled sample comes back positive, then each sample needs to be tested individually to find out which was positive.

…Today, the FDA is taking another step forward by updating templates for test developers that outline the validation expectations for these testing options to help facilitate the preparation, submission, and authorization under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

This is good and will increase the effective number of tests by at least a factor of 2-3 and perhaps more.

In other news, Representative Beyer (D-VA), Representative Gonzalez (R-OH) and Paul Romer have an op-ed calling for more prizes for testing:

Offering a federal prize solves a critical part of that problem: laboratories lack the incentive and the funds for research and development of a rapid diagnostic test that will, in the best-case scenario, be rendered virtually unnecessary in a year.

…We believe in the ability of the American scientific community and economy to respond to the challenge presented by the coronavirus. Congress just has to give them the incentive.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have already begun a similar strategy with their $1.4 billion “shark tank,” awarding speedy regulatory approval to five companies that can produce these tests. Expanding the concept to academic labs through a National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST)-sponsored competition has the added benefit ultimately funding more groundbreaking research once the prize money has been awarded.

This is all good but frustrating. I made the case for prizes in Grand Innovation Prizes for Pandemics in March and Tyler and I have been pushing for pooled testing since late March. We were by no means the first to promote these ideas. I am grateful things are happening and relative to normal procedure I know this is fast but in pandemic time it is molasses slow.

The economics of pandemic preparation

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one short excerpt:

…most of the vaccine-making capacity against a new virus would be concentrated in a few multinationals, and much of that activity occurs outside the U.S. If a pandemic were to become truly serious, politics might intervene and prevent the export of doses of the vaccine, no matter what the price.

The economic case for free trade is entirely sound. But here is one case where the U.S. government should take the initiative to support a domestic vaccine industry — because that trade is unlikely ever to be free.

And if you think the market will provide the solution, consider that potential suppliers may fear being hit with price caps, IP confiscations, or other after-the-fact “takings” by the U.S. government. So it is important to think now about how to create the right structures for the eventual creation of treatments and cures.

In the meantime, wash your hands! Nonetheless, so far the smart money still ought to bet that this one will evolve into less virulent forms, and it already seems that a disproportionate number of the people dying are quite old.

Is Elon Musk Prepping for State Failure?

FuturePundit on twitter has an interesting theory of Elon Musk’s technology portfolio, namely a lot of it will be very valuable for living in a failed state.

Solar panels, for example, are a necessity when the state can’t deliver power reliably, as is now the case in California.

Solar panels plus the Tesla give you mobility, even if Saudi Arabia goes up in smoke and world shipping lines are shut down.

Starlink, Musk’s plan for 12,000 or more cheap, high-speed internet satellites, will free the internet from reliance on any terrestrial government.

Musk’s latest venture, the truck, certainly fits the theme and even if the demonstration didn’t go as well as planned isn’t it interesting that the truck is advertised as bulletproof. Mad Max would be pleased.

And what will you be carrying in your Tesla truck? One of these for sure.

Finally, the Mars mission is the ultimate insurance policy against failed states.

How to prepare for CRISPR

That is an MR reader request, namely:

One issue that it appears we’ll discuss more in the future is genetic experimentation – the sort heralded by CRISPR. How do you suggest we prepare for this technology? What should be reading? Discussing?

Read my book The Age of the Infovore, to better understand the importance of human diversity, and also ponder my earlier post on whether genetic engineering will lead to excess human conformity. Then investigate what kinds of sperm and eggs are most popular and thus most expensive on the current market; that’s tall, smart people who look a bit like the parents. That might give us an idea of what kind of genetic engineering people are trying to accomplish. Then watch or rewatch Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. If you still have spare time, dip into the New Testament again.

Then read about extensive Chinese efforts in this area. Consider also how slow advances have been in genomics, and how difficult manipulability will be for most issues. Then study Moore’s Law and Big Data. Then read about how unlikely regulation will be able to stop advances in this area (the biggest intellectual gap in this set of instructions). Then read or reread Aldous Huxley and any Greek tragedy centering around the idea of hubris.

Mix together, stir, shake, and sit down and cry.

Is the Indian left preparing its cave-in on FDI?

It seems there is still some fight left in them:

…leftwingers inside and outside the Congress party, including a few of Mr Singh’s allies in the multi-party coalition, oppose economic liberalisation and in some cases regard retail reform as a capitalist plot masterminded by Walmart.

“The tragedy is that our prime minister has begun to worship the US,” said Sitaram Yechury, leader of the opposition Communist Party of India – Marxist. “Congress wants Indians to be slaves and foreigners to be our masters. We will not accept FDI [foreign direct investment] in retail. We will protest this decision till our last breath.”

On the political right, BJP leaders – backed by small shopkeepers wary of retail competitors – sense an opportunity to destabilise the government before its term expires in 2014 and are not shy in pursuing that goal through short-term alliances with the hard left.

Developing…

Means testing for Medicare

Let’s first quote Mark Thoma’s response to my column; it is indirectly a good summary of what I argue:

I believe the political argument that giving everyone a stake in the

program helps to preserve it has more validity than Tyler does, market

failures (some of which hit all income groups) probably play a larger

role in my thinking about government responses to the health care

problem than in his, and I have more confidence than Tyler that a

universal care system has the potential to lower costs.

And now here’s me:

…the idea of cutting some government transfers provokes protest in

some quarters. One major criticism is that programs for the poor alone

will not be well financed because poor people do not have much political

power. Thus, this idea goes, we should try to make transfer programs as

comprehensive as possible, so that every voter has a stake in the

program and will support more spending.But even if this argument

holds true now, it may not be very persuasive when Medicare costs start

to push taxation levels above 50 percent. A more modest program, more

directly aimed at those who need it, might prove more sustainable in

the longer run.Americans have supported the growth of many

programs aimed mainly at the poor. Both Medicaid and the Earned Income

Tax Credit have grown rapidly in size since their inception. The idea

of helping the poor and not having the government take over entire

economic sectors was the original motive behind welfare programs, in

any case.Furthermore, the argument for comprehensive and

universal transfer programs does not meet the ideal of democratic

transparency. If taking care of the poor is the real value in welfare

programs, those programs should be sold as such to the electorate. We

shouldn’€™t give wealthier people benefits just to €œtrick€ them, for

selfish reasons, into voting for greater benefits for everyone, the

poor included.

Here is another point:

Advocates of health care reform tend to be long on ideas for expanding

care and access, but short on practical solutions for cost control. The

argument is often made that single-payer health care systems in Canada

or Europe are cheaper than health care in the United States. But

Medicare is already a single-payer plan, yet its costs are

unsustainable.

Note that I am calling for higher benefits for the poor and lower benefits for higher-income groups. That’s not a popular stance, not even with egalitarians. In fact I view the contemporary left as oddly ill-prepared on the health care issue. Electorally speaking, the issue is fully 100 percent in their court (and they are used to pressing it aggressively), until of course they get their way and have to "meet payroll," so to speak. One attitude is to cite Europe and think that the production possibilities frontier can expand under better management of the U.S. system, even as you cover an extra 40 million people. Another attitude is to face the notion of trade-offs.

Here is the full column. (By the way, I think that HSAs are ineffective as health care reform and that the so-called "right" is floundering on

this issue, just to get in my equal opportunity smack on the blog.)

Addendum: You can make a good argument that (some) public health programs are the best health care investment of all; I just didn’t have enough space in the column to cover that issue.

Second addendum: Greg Mankiw didn’t read so closely. It’s not "an income tax surcharge on sick, old people." It’s a reallocation of benefits toward people of greater need. Is any benefit less than infinity an "income tax surcharge"?

Third addendum: Here is Paul Krugman on the topic.

My Conversation with Byron Auguste

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is my introduction:

TYLER COWEN: Today I am here…with Byron Auguste, who is president and co-founder of Opportunity@Work, a civic enterprise which aims to improve the US labor market. Byron served for two years in the White House as deputy assistant to the president for economic policy and deputy director to the National Economic Council. Until 2013, he was senior partner at McKinsey and worked there for many years. He has also been an economist at LMC International, Oxford University, and the African Development Bank.

He is author of a 1995 book called The Economics of International Payments Unions and Clearing Houses. He has a doctorate of philosophy and economics from Oxford University, an undergraduate econ degree from Yale, and has been a Marshall Scholar. Welcome.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: As you know, more and more top universities are moving away from requiring standardized testing for people applying. Is this good or bad from your point of view?

AUGUSTE: I think it’s really too early to tell because the question is —

COWEN: But you want alternative markers, not just what kind of family you came from, what kind of prep you had. If you’re just smart, why shouldn’t we let you standardize test?

AUGUSTE: I think alternative markers are key. This is actually a pretty complicated issue, and I’ve talked to university administrators and admissions people, and it’s interesting, the variety of different ways they’re trying to work on this.

But I will say this. If you think about something like the SAT, when it first started — I’m talking about in the 1930s essentially — it was an alternative route into a college. It started with the Ivies. It was started with James Conant and Harvard and the Ivies and the Seven Sisters and the rest, and then it gradually moved out.

The problem they were trying to solve back in the ’30s was that up until that point, the way you got into, say, Dartmouth is the headmaster of Choate would write to Dartmouth and say, “Here’s our 15 candidates for Dartmouth.” Dartmouth would mostly take them because Choate knew what Dartmouth wanted. Then you had the high school movement in the US, where between 1909 and 1939, you went from 9 percent of American teenagers going to high school to 79 percent going to high school.

Now, suddenly, you had high school students applying to college. They were at Dubuque Normal School in Iowa. How does Dartmouth know whether this person was . . . The people from Choate didn’t start taking the SATs, but the SAT — even though it was a pretty terrible test at the time, it was better than nothing. It was a way that someone who was out there — not in the normal feeder schools — could distinguish themselves.

I think that is a very valuable role to play. As you know, Tyler, the SAT does, to some extent, still play that role. But also, because now that everybody has had to use it, it also is something that can be gamed more — test prep and all the rest of it.

COWEN: But it tracks IQ pretty closely. And a lot of Asian schools way overemphasize standard testing, I would say, and they’ve risen to very high levels of quality very quickly. It just seems like a good thing to do.

Most of all we cover jobs, training/retraining, and education. Interesting throughout.

Top Ten MR Posts of 2014

Here is my annual rundown of the top MR posts of 2014 as measured by page views, tweets and shares.

1. Ferguson and the Debtor’s Prison–I’d been tracking the issue of predatory fining since my post on debtor’s prisons in 2012 so when the larger background of Ferguson came to light I was able to provide a new take on a timely topic, the blogging sweet spot.

2. Tyler’s post on Tirole’s win of the Nobel prize offered an authoritative overview of Tirole’s work just when people wanted it. Tyler’s summary, “many of his papers show “it’s complicated,” became the consensus.

3. Why I am not Persuaded by Thomas Piketty’s Argument, Tyler’s post which links to his longer review of the most talked about economics book of the year. Other Piketty posts were also highly linked including Tyler’s discussion of Rognlie and Piketty and my two posts, Piketty v. Solow and The Piketty Bubble?. Less linked but one of my personal favorites was Two Surefire Solutions to Inequality.

4. Tesla versus the Rent Seekers–a review of franchise theory applied to the timely issue of regulatory restrictions on Tesla, plus good guys and bad guys!

5. How much have whites benefited from slavery and its legacy–an excellent post from Tyler full of meaty economics and its consequences. Much to think about in this post. Read it (again).

6. Tyler’s post Keynes is slowly losing (winning?) drew attention as did my post The Austerity Flip Flop, Krugman critiques often do.

7. The SAT, Test Prep, Income and Race–some facts about SAT Test Prep that run contrary to conventional wisdom.

8. Average Stock Returns Aren’t Average–“Lady luck is a bitch, she takes from the many and gives to the few. Here is the histogram of payoffs.”

9. Tyler’s picks for Best non fiction books of 2014.

10. A simple rule for making every restaurant meal better. Tyler’s post. Disputed but clearly correct.

Some other 2014 posts worth revisiting; Tyler on Modeling Vladimir Putin, What should a Bayesian infer from the Antikythera Mechanism?, and network neutrality and me on Inequality and Masters of Money.

Many posts from previous years continue to attract attention including my post from 2012, Firefighters don’t fight fires, which some newspapers covered again this year and Tyler’s 2013 post How and why Bitcoin will plummet in price which certainly hasn’t been falsified!

The culture that is Manhattan James Heckman gone wild edition

A mad-as-heck Manhattan mom says her daughter’s Ivy League dreams have been all but dashed — and she’s only 4 years old.

Nicole Imprescia is suing the $19,000-a-year York Avenue Preschool, saying her daughter, Lucia, was forced to spend too much time with lesser-minded 2- and 3-year-olds when she should have been focusing on test preparation to get into an elite elementary school.

The suit, filed in Manhattan Supreme Court, notes that “getting a child into the Ivy League starts in nursery school” and says the Upper East Side school promised Imprescia it would “prepare her daughter for the ERB, an exam required for admission into nearly all the elite private elementary schools.”

But “it became obvious [those] promises were a complete fraud,” the suit says. “Indeed, the school proved not to be a school at all but just one big playroom.”

The miffed mom yanked her daughter after just three weeks — but the school is refusing to refund the $19,000 she had to pay up front, said her lawyer, Mathew Paulose.

The article is here. For the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.