Results for “antibiotic” 59 found

The economics of antibiotics

Ezekiel J. Emanuel writes:

The big problem is profitability. Unlike drugs for cholesterol or high blood pressure, or insulin for diabetes, which are taken every day for life, antibiotics tend to be given for a short time, a week or at most a few months. So profits have to be made on brief usage. Furthermore, any new antibiotics that might be developed to fight these drug-resistant bacteria are likely to be used very sparingly under highly controlled circumstances, to slow the development of resistant bacteria and extend their usefulness. This also limits the amount that can be sold.

The new Obama plan to combat antibiotic overuse

The Obama administration on Thursday announced measures to tackle the growing threat of antibiotic resistance, outlining a national strategy that includes incentives to spur the development of new drugs, tighter stewardship of existing ones and a national tracking system for antibiotic-resistant illness. The actions are part of the first major federal effort to confront a public health crisis that takes at least 23,000 lives a year.

The full story is here.

The Hill has more detail. It is an executive order:

The president’s directive creates the Task Force for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, co-chaired by the secretaries of Defense, Agriculture and Health and Human Services.

The group is charged with implementing a plan to track and prevent the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, promote better practices for the use of current drugs and push for a new generation of antibiotic medications.

To that end, the White House on Thursday announced a $20 million prize “to facilitate the development of rapid, point-of-care diagnostic tests for healthcare providers to identify highly resistant bacterial infections.”

The added incentive and the timeframe given to the task force indicate the urgency with which the administration is acting, said Dr. Eric Lander, who co-chairs the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

“This is a pretty tight timeline to now come up with a national game plan,” Lander said.

There is also this:

In December, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) unveiled a plan to phase out the use of antimicrobials for the purpose of fattening chickens, pigs or other animals destined for human consumption. But the plan relies in part on voluntary industry cooperation, and advocates argue the government’s efforts are lagging behind even some industry players.

Here is the new full 78 pp. report to the President on antibiotic resistance (pdf).

This initiative — or its failure — is potentially a more important health issue than Obamacare, yet it will not receive 1/1000th of the attention. Without reliable antibiotics, a lot of now-routine operations would become a kind of lottery.

Here are previous MR posts on antibiotic resistance. I would note it is difficult to judge such a plan at the current level of detail. It is better than nothing, but any initial plan is going to be not nearly enough, relative to an ideal. By the way, Alex tells me there is also a British prize, discussed here.

Antibiotic resistance

The E coli strain that is killing people in Europe is both new and resistant to at least a dozen antibiotics in eight classes. It’s clear, therefore, that this strain picked up resistance via gene transfer from previous strains that evolved resistance over a longer time frame. Thus, antibiotic resistance can spread very quickly, probably more quickly than we can develop new antibiotics. One of the places that resistance develops is in farm animals where antibiotics are used as growth promoters, not just as therapeutics. Since there is a significant externality from antibiotic use, there is a good case to be made for regulating antibiotic use. As Glenn Reynolds once put it:

I think you can make a better case for regulating antibiotics than heroin: Misusing antibiotics can endanger countless others, while misusing heroin mostly endangers oneself.

(FYI, Tyler and I use antibiotic use as an important example of externalities in Modern Principles).

Denmark progressively regulated and reduced antibiotics for sub-therapeutic use in pigs, poultry and other livestock beginning around 1995. After some experimentation, pig production was not adversely affected and resistance in the wild declined. It’s less clear whether human health increased due to the regulation of antibiotics in farm animals (although there is less resistance in countries that use fewer antibiotics). It may be that Denmark is simply too small and connected with the rest of the world to see a large effect. Nevertheless, Denmark shows us that the costs of reducing antibiotic use in farm animals is not excessive, especially if phased-in, and the benefits of maintaining the effectiveness of our stock of antibiotics is so high that I see more intelligent but reduced use as an important goal.

See also Megan McArdle’s very good talk on this topic.

Thursday assorted links

1. The Milei deregulation announcements (in Spanish). Here is the recorded message, with subtitles.

2. “Nearly 4% of Cuba’s population reached the U.S.-Mexico border in fiscal years ‘22-23.” Link here, have you noticed that Latin America is central to the news again?

3. AI discovers a new structural class of antibiotics. And “The authors got GPT-4 to autonomously research, plan, and conduct chemical experiments, including learning how to use lab equipment by reading documentation (most were operated by code, but one task had to be done by humans)”, link here.

4. Cowen’s Second Law: “The survival time of chocolates on hospital wards: covert observational study.”

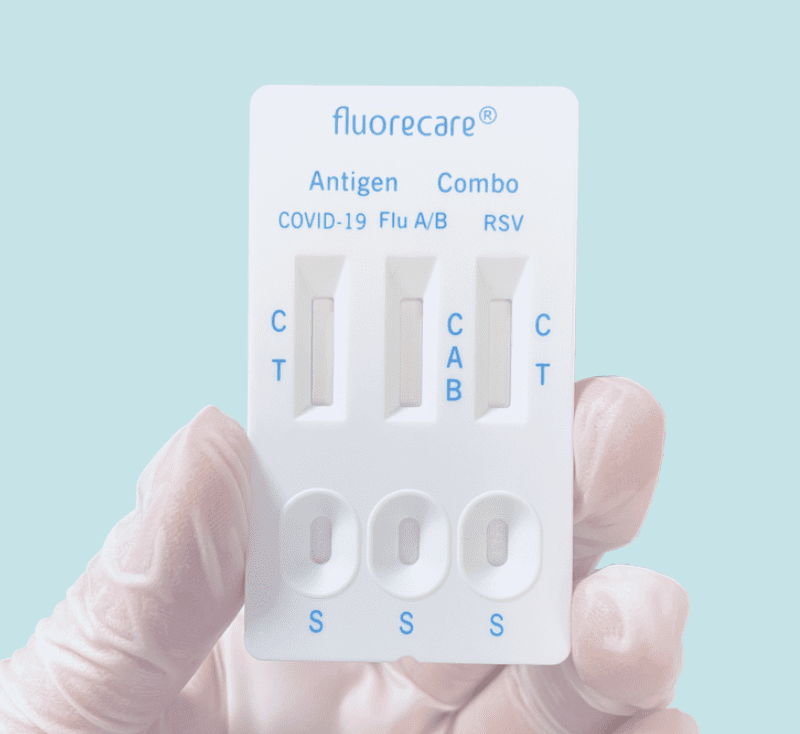

Combination Rapid Tests

Once again, the US is behind on at-home rapid antigen tests–this time on combination tests that let you test for COVID, Influenza, and RSV all at once. These tests are widely available in Europe but have not been approved by the FDA. Rapid flu tests especially are potentially very useful in assigning appropriate treatment and reducing the overuse of antibiotics.

From the comments, on CDC reform

These are the word of commentator Sure:

*The Deep Places: A Memoir of Illness and Discovery*

That is the new forthcoming Ross Douthat book, focusing on his struggles with Lyme disease. It is very much a memoir, starting with talk of Connecticut, deer, and his family’s dream house, all leading to an unfortunate bite from a tick. Visits to many doctors ensue, motivated by chronic pain and weakness.

Overall this is a book about the medical establishment, the psychological path of coming to terms with one’s own illness (a kind of Krankheitsbildungsroman), how bureaucracy shapes science, and a plea that a lot of people really are chronically sick rather than psychosomatic or malingerers. It is Ross’s best-written book, and it has echoes of Susan Sontag and also Robert Burton.

If I understand Ross correctly, he is pro-antibiotic use under these circumstances, at least for his individual case. I do not myself have any opinion about the various medical views expressed in this work. Even prior to reading this book, my intuition was to believe that chronic Lyme disease is very much real, but that is not based upon aggregating a great deal of information. In any case, Covid and the response of the public health establishment have made the relevance of this book much clearer. The discussion here doesn’t give you much reason to trust them more.

I believe we are entering a new era where public intellectuals have an increasing degree of “medical sway.”

This is also a tale, under the surface, of how “the privileged” interact with the medical establishment in a fundamentally different way (I don’t mean that as snark or whining).

Here is an update on one potential Lyme disease vaccine. Was the previous vaccine really so bad?

How should you react if electromagnetic stimulation appears to improve your symptoms?

NB: I don’t like walking in the woods.

What should we regulate *more*?

Since the Biden team does not seem too favorably disposed to deregulation, perhaps it is worth asking in which areas we should be pushing for additional regulation. Here are a few possible picks, leaving pandemic-related issues aside, noting that I am throwing these ideas out and in each case it will depend greatly on the details:

1. Air pollution. No need to go through this whole topic again, carbon and otherwise. Remember the “weird early libertarian days” when all air pollution was considered an act of intolerable aggression?

2. Noise pollution. There is good evidence of cognitive effects here, but what exactly are we supposed to do? Can’t opt for NIMBY now can we!?

3. Something around chemicals? How about more studies at least?

4. Housing production. You can look at this as more or less regulation depending on your point of view. But perhaps cities of a certain size should be required by the state government to maintain sufficient affordability.

5. Mandates for standardized reporting of data? For example, the NIH requires that scientists report various genomic data in standardized ways, and this is a huge positive for science. What else might work in this regard?

6. Federal occupational licensing, in lieu of state and local.

7. Software as a service from China?

8. Animal welfare and meat production.

9. Is there a useful way to regulate to move toward less antibiotic use?

10. Should we have more regulation of AI that measures human emotions? How about facial and gait surveillance in public spaces?

11. How about regulating regulation itself?

What else?

I thank an MR reader for some useful suggestions behind this post.

Emergent Ventures winners, 12th cohort

Markus Strasser, from Linz and now London, to work on natural language processing for scientific outputs.

Andres Leon, a 17-year-old from Mexico City who is building a mobile payments company with his brother.

Ifat Lerner, Lerner Labs, a new venture customizing education for K-12 students.

Brianna Wolfson, for a start-up focused on teaching corporate culture.

Mukundh Murthy, 17-year-old from Massachusetts, studies biology, computational biology, and antibiotic resistance; the award is for general career development.

Youyang Gu, here are his Covid-19 projections using machine learning. Here is his recent blog post.

Matt Faherty, to study and write about the NIH.

*The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940-1941*

The author is Paul Dickson, and the subtitle is The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor.

For one thing, I enjoyed the examples of “fast action” in this book. For instance, the U.S. passed draft registration Sept.16, 1940. All men between 21 and 45 are supposed to register, and on a single date, Oct.16. Almost all of them do, including people in mental hospitals. Some stragglers register over the next five days, but the overwhelming majority pull it off on day one, and with very little preexisting infrastructure to draw upon, as draft institutions had been abolished right after the end of WWI.

I had not realized how instrumental George Marshall had been, before Pearl Harbor, in investing in building up America’s officer corps.

The famous movie star, Jimmy Stewart, was drafted but then rejected for being ten pounds too light at 6’3″ and 138 lbs. He then put on ten pounds so he could join the service.

The tales of poor morale, mental illness, and prostitution camps (no antibiotics!) in 1940 are harrowing.

Recommended.

What I’ve been reading

1. Daniel Halliday and John Thrasher, The Ethics of Capitalism: An Introduction. This book is reasonable, empirical, non-dogmatic, readable, and largely but not uncritically pro-capitalist. It is indeed “an introduction,” and not designed for say yours truly, but we need many more works like this.

2. Ken McNab, And in the End: The Last Days of the Beatlesxxx. I regularly opine that sports and entertainment books — provided you already have familiarity with the topic area — provide better management lessons than do management books. This volume, as I read it, presents the Beatles story as a tale of two sequential founders — first John (who had most of the early excellent songs), and then Paul, the turning point in my view being when Paul commandeered the engineering of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” otherwise very much a John song but in fact Paul did most of the actual work on it. Eventually the first founder rebelled against the ever-more-domineering second founder, and then the Beatles went poof.

3. Martyn Rady, The Habsburgs. Most books about the Habsburgs confuse me, this one confuses me less than those other ones, consider that a recommendation. I learned the most from the section about all of the early ties to what is now part of northern Switzerland.

4. Jeff Selingo, Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions. Most books about college admissions do not confuse me (the reality already is so absurd), but this one informs me, consider that a recommendation. Selingo has done actual extensive research, including a direct pipeline into the processes of several major institutions, and he puts informativeness above moralizing or exaggeration.

5. Richard E. Spear, Caravaggio’s Cardsharps on Trial: Thwaytes v. Sotheby’s. A surprisingly taut and suspenseful treatment of a dispute and then lawsuit over whether a supposed Caravaggio was in fact “real” or not. NB: if they have to ask whether or not it is real, most of the time it ain’t.

6. William C. Summers, Félix d‘Hérelle and the Origins of Molecular Biology. I wanted to read up on bacteriophages, in part as a broader proxy for abandoned lines of scientific inquiry (superseded by antibiotics, and did you recall they play a big role in Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith?), and it seemed this was the right book for that. Short enough and to the point, clear enough for the non-specialist, and it has plenty on the history of science more broadly. It also covers d’Hérelle being invited to Georgia, USSR, to pursue his research, a fascinating episode in his life. For a brief introduction, here is his Wikipedia page.

7. Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, The Discomfort of Evening. A few months ago I started reading this one, figuring it would win a Booker, and indeed it just did. I read up through p.102, and quite liked it, but also figured that a Dutch farm tale of mucky perversion, flapping meats, and a mordant, vibrant nature did not in fact fit into my broader life plan. Indeed it did not. But if you are considering this one, while likely I will not finish it, I still would nudge you slightly in the positive direction. Cumin cheese makes an appearance (ugh).

I have not had a chance to read Adrian Goldworthy’s Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conqueror, but it appears promising.

Steven Ozment, The Age of Reform, 1250-1550: An Intellectual and Religious History of Late Medieval and Reformation Europe is a reprint of a 1980 classic, with an emphasis on the roots of liberalism in European religious thought.

How many lives is hospitalization saving in the pandemic?

Do we have evidence that hospitalization of COVID19 patients is actually saving significant numbers of lives?

I’ve now seen multiple studies suggesting that up to 80 or 90 percent of patients who end up on ventilators ultimately die. At this point, I guess there’s no way to know if the other 10 percent would have lived without the ventilators. From what I can tell, most other hospitalized patients are getting supplemental oxygen, IV fluids and antibiotics. I have not seen any evidence on the effectiveness of these treatments. Many of those patients live, but we don’t know whether they would have recovered without hospitalization. It would obviously be impossible to do a RCT on that at the moment.

Answering the question about the efficacy of hospitalization would seem to be critical, though, since, as best I can tell, the main justification for shutting down society now is to prevent our health care system from being overwhelmed – especially the supply of ventilators. If our hospitals are overwhelmed, not only COVID19 patients, but others with treatable injuries/diseases might die. But if hospitalization is not actually saving COVID19 patients in large numbers, then all the costly social interventions we are implementing now are mostly just delaying the spread of infection. Still, I recognize that it’s possible that this delay could save lives in one of two ways (or maybe there are more I’m not thinking of?).

1. We use the time to get better at testing. Then, when we lift the social distancing measures in a month or two, we have the ability to quickly test and isolate infected individuals and their close contacts. Maybe we also have anti-body tests so we can avoid quarantining immune individuals. This keeps the rate of spread relatively low until we have better treatments or a vaccine for those who haven’t been infected yet. It’s possible that “at-risk” groups will have to stay isolated during this time until we get effective treatments/vaccine. I haven’t seen any estimates of how effective this kind of strategy might be – i.e., over a course of 18 months (the time to develop/deploy a vaccine) how many infections would this prevent?

2. We could keep the social distancing policies in place until we get a vaccine/treatment. But if estimates of 18+ months to a vaccine are correct, I suspect the economic costs will be too high to bear to wait it out this way. So this is probably not in the cards.

If the number of lives we can save with #1 is relatively low (I have no idea what the number is), and if #2 is off the table, then we are really just delaying most deaths, at great social cost. It might be better to prevent our hospitals from being overwhelmed by doing better triage for admission – especially to ICU beds and ventilators (what percent of people over age 75 survive after going on a ventilator?), and working on getting people other treatments (oxygen, etc.) at home. At a minimum, it seems like the intense energy and resources focused on ventilators now might be misplaced.

For what it is worth, I’m not a skeptic of the current social distancing policies. I’m pretty sure I’d be doing all this and more if I were in charge. But I’d also be looking for evidence that what we are doing is the best course of action, given the massive costs.

That is an email from a very smart person. To that tally we also must add the negative that hospitals often become a vector for the further spread of the virus.

So what does the best evidence say here?

Draining the swamp

From Jason Crawford, Emergent Ventures winner in Progress Studies:

…the surprising thing I found is that infectious disease mortality rates have been declining steadily since long before vaccines or antibiotics…

In 1900, the most deaths came from tuberculosis, influenza/pneumonia, and gastroenteric diseases such as dysentery. All of these were effectively conquered by antibiotics in the 1930s and ’40s, but were on the decline since at least the beginning of the century…

Indeed, digging further into the UK data from the late 1800s, we can see that TB was declining since at least 1850 and gastroenteric disease since the 1870s. And similar patterns hold for lesser killers such as measles, which didn’t have a vaccine until the 1960s, but which by then had already declined in mortality by more than 90% from its 1900 levels.

So what was going on? If you read my survey of technologies against infectious disease, you know that other than drugs and immunization, there is one other way to fight germs: cleaning up the environment.

I was surprised to learn that sanitation efforts began as early as the 1700s—and that these efforts were based on data collection and analysis, long before a full scientific theory of infection had been worked out.

There is much more at the link, including the footnotes for citations to the claims made here.

Public health is no longer an O-Ring production function

In the bad old days, health care in poor countries was just terrible. It wasn’t only the poverty, lack of hospitals and pharmaceuticals, and unsanitary conditions. In addition, doctors gave very bad advice and they also didn’t work very hard, as outlined in this paper. Citizens suffered accordingly.

Those conditions have improved somewhat, but actual health outcomes have improved a lot. You still can’t trust the local medical advice in Tanzania, but guess what? You have much better vaccines, greater access to antibiotics, more NGOs running health clinics, and better health care information, sometimes through the internet. If your kid has diarrhea, let the kid drink water, even unclean water! As for antibiotics (NYT):

Two doses a year of an antibiotic can sharply cut death rates among infants in poor countries, perhaps by as much as 25 percent among the very young, researchers reported on Wednesday.

In other words, the quality of the most important part of health care treatments bypassed the rest of the problems in poor economies and grew rapidly, even in countries with only so-so economic growth. The rate of reduction in child mortality has tripled in many countries since the 1990s, and by no means are those locales major economic winners as say Singapore and South Korea were.

Therein lies one of the most important (and under-reported) global changes in the last twenty years. It is now possible to have a decent public health system in a country with poor or mediocre political and economic institutions.

In other words, public health is no longer such an O-Ring service, an O-Ring service being one where everything has to go right for the service to be of decent quality. And advances are much, much easier when the O-Ring structure no longer rules.

The O-Ring citation is to a famous Michael Kremer paper — a trip to the moon is definitely an O-Ring process, because if one step is off the whole mission probably is a failure. But tasty fish curry is not — you can get a splendid version in some pretty dumpy countries, maybe even a better version in poorer places.

Electricity, however, it seems is still an O-Ring service, as evidenced by the recent power blackouts in South Africa.

What else is likely to become less of an O-Ring good or service in the next few decades to come? And what can we do to hasten such progress? Is there any chance of quality software production making that same kind of transition? Or might some goods and services return to a greater connection with the O-Ring model?

For this post I am very much indebted to a conversation with Garett Jones.

The Tremendous Value of Increases in Life Expectancy

In this post I shall argue two things which together may confuse people. First, that life expectancy is so valuable that the money the US spends on healthcare relative to Europe could be well spent. Second that the extra spending is not in fact due to higher quality and does not explain rising prices over time.

What explains rising prices in some sectors of the economy? A common argument, at least from economists, is that there may be unmeasured improvements in quality. I don’t think that there have been marked improvements in quality in education so that argument doesn’t get off the ground (see my earlier post and the book for evidence). But health care quality has increased. Moreover, the value of life is so high that the improvements in quality could justify the cost increases. Here from Why Are The Prices So D*mn High is a back of the envelope calculation:

The United States spends about 5 percent more of GDP on health-care than do other developed countries. US GDP is almost $20 trillion, so 5 percent is approximately $1 trillion. The US population is 325 million, so the United States spends an extra $3,000 per person each year on healthcare. Is the expense worthwhile?

A value of a statistical life-year of around $200,000 is a mid-range, widely used estimate in the United States. Thus, if the extra US spending generated an extra $3,000 per $200,000 of a life-year, it would pay for itself. In other words, for the extra US spending to be worthwhile it must generate 3,000/200,000 × 365 = 5.45 extra days of statistical life, and, of course, it must do so every year. In recent years, life expectancy in the United States has increased by about 52 days a year. Thus, a little more than 10 percent of the increase in actual life expectancy must be a result of the extra US spending for that spending to be worthwhile. That hardly appears impossible. It’s also not impossible that the increase in life expectancy was not caused by the extra spending.

The bottom line is that the value of life is so high that US levels of spending could be worthwhile, but the high value of life and the difficulty of measuring the effectiveness of healthcare makes the question impossible to answer with certainty.

Nevertheless,I don’t think the increases in quality explain the increases in cost:

…even if the spending on healthcare is well justified by the improvements in life expectancy, it does not follow that the cause of higher spending is the improvement in life expectancy. As with education, many of the increases in life expectancy come from better knowledge, which does not necessarily cost more to use. It does not cost much more to treat an infection with antibiotics than with bloodletting; perhaps it costs less. We do use more technology in healthcare than in previous years—this includes computerized tomography (CT) scanners, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems, and positron emission tomography (PET). Technology, however, is falling in price. At some point one would expect that decreases in the cost of existing technologies would overwhelm increases in costs owing to the introduction of new technologies. As with education, it would be peculiar if the only place in which technology raised costs was in healthcare (but see Joseph P. Newhouse for a strong argument that healthcare costs are driven by technology.)

Let’s put this argument more generally. Most increases in quality *over time* are similar to increases in productivity, i.e. A in A*f(K,L), an unpriced factor. Computers today are much higher quality than in the past. Indeed, so much so that today’s computers couldn’t be bought at any price not that long ago but we don’t pay more because what makes them higher quality is general knowledge.

In my view, most quality increases over time are due to improvements in knowledge. In other words, quality increases over time are much more about better recipes than better cooks. As a result, at a given point in time, higher quality is associated with higher prices but over time higher quality is more often associated with *lower* prices. Thus, in general, higher quality is not a good explanation for higher prices over time.

Tomorrow: The Baumol Effect.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

Here is the original post.