Results for “caplan signal education” 27 found

How much of education and earnings variation is signalling? (Bryan Caplan asks)

On Twitter Bryan asks me:

Would you state your human capital/ability bias/signaling point estimates using my typology?

He refers to this blog post of his, though he does not clearly define the denominator there: is it percentage of what you spend on education or explaining what percentage of the variation in lifetime earnings? I’ll choose the latter and also I’ll focus on signaling rather than trying to separate out which parts of human capital are from birth and which are later learned. My calculations are thus:

1. I don’t wish to count “credentialed” occupations, where you need a degree and/or license, but you are reaping rents due to monopoly privilege. It’s neither human capital nor signaling (it’s not about intrinsic talent), though you could argue it is a kind of human capital in rent-seeking. In any case, let’s focus on private labor markets without such barriers.

2. Most capital and resource income is due to factors better explained by human capital theories or due to inheritance. That is more than a third of earnings right there. Note that the higher is inequality, the less the signaling model will end up explaining. That is one reason why the signaling model has become less relevant.

3. Depending on job and sector, what you’ve signaled, as opposed to what you know, explains a big chunk of wages in the first three to five years of employment. Within five years (often less), most individuals are earning based on what they can do, setting aside credentialism as discussed under #1. Here is my earlier post on speed of employer learning.

Keep in mind that everyone’s wages change quite a bit over their lifetime and that is mostly not due to retraining (i.e., changes in the educational signal) in the formal sense, as most people stop formal retraining after some point. The changes are due to employer estimates of skill, modified by bargaining power. In this sense all theories are predominantly human capital theories, whether they admit it or not.

To be generous, let’s give Bryan the full first five years of income based on signaling alone, out of a forty year career. And let’s say that on average wages rise at the rate of time discount (not true as of late, but a simplifying assumption and I think Bryan believes in a claim like this anyway.)

How much of income is explained by signaling? I’m coming up with “1/8 of 2/3,” the latter fraction referring generously to labor’s share in national income. That will fall clearly under ten percent, but recall I’ve inserted some generous assumptions here.

Bryan wants to call me “a signaling denialist,” yet I see signaling as still very important for understanding some aspects of the labor market. But it’s far from the main story for the labor market as a whole, especially as you move into the out years.

That all said, this “decomposition” approach may obscure more than it illuminates. Let’s consider two parables.

First, imagine a setting where you need the signal to be in the game at all, but after that your ingenuity and your personal connections explain all of the subsequent variation in income. Depending what margin you choose, the contribution of signaling to later income can be seen as either zero percent or one hundred percent. Signaling won’t explain any of the variation of income across people with the same signal, yet people will compete intensely to get the signal in the first place.

Second, in a basic signaling model there are two groups and one dimension of signaling. That’s too simple. A signaling model implies that a worker is paid some kind of average product throughout many years, but of course the reference class for defining this average product is changing all the time and is not, over time, based on the original reference class of contemporaneous graduating peers. For the purposes of calculating your wage based on a signal, is your relevant peer group a) all those people who got out of bed this morning, b) all those people in the Yale class of 2012, or c) all those who have been mid-level managers at IBM for twenty years? This will change as your life passes.

So there’s usually a signaling model nested within a human capital model, with the human capital model determining the broader parameters of pay, especially changes in pay. The employer’s (reasonably good but not perfect) estimate of your marginal product determines which peer group you get put into, if you choose to invest in additional signals (or not). The epiphenomena are those of a signaling model, but the peer group reshufflings over time are ruled by something else. Everything will look like signaling but again over time signaling won’t explain much about the variation or evolution in wages.

Seeing the relevance of those “indeterminacy” and “nested” perspectives is more important than whatever decomposition you might cite to answer Bryan’s query.

Bryan Caplan’s signaling model and on-line education

The very useful model is here, and there is further commentary from Bryan here. My question is this: does the model imply that on-line education should succeed, or not?

Let’s say that education signals conscientiousness. A purely on-line class, with no ogre standing over your shoulder to discipline you, should be blown off by those who are not conscientiousness. The on-line class would seem to offer a better signal and a cleaner separation of types.

Alternatively, let’s say education signals IQ or some other notion of “smarts.” On-line education would seem to offer less opportunity to get through by buttering up the teacher, spouting mumbo-jumbo in basket-weaving classes, and so on. For better or worse, a lot of on-line education seems to be based on relatively objective tests. Then on-line education would seem to offer a better signal of smarts.

One possible application of Bryan’s model might be this. Income inequality is rising, so there is greater care to get the signal, selection, and screening right for top jobs. Relatively high levels of education should be all the more discriminatory, and that may mean more on-line education. In fact, in normative terms that might well be a problem with on-line education, namely its inegalitarian nature with regard to curiosity and effort and smarts.

Oddly, the signaling model could be true, but through an invisible hand mechanism — schools competing to separate quality in the most effective ways — you can end up with a state of affairs where upfront signaling costs are fairly low. Imagine a chess school, needing to sort talent, and unable to teach its students very much, but setting up a quite cheap on-line tournament and declaring some winners. Aren’t the Khan Academy users some really talented people?

Alternatively, through an invisible hand mechanism, if the learning model is correct, you could end up with an equilibrium in which upfront signaling costs appear to be relatively high, namely that you impose “taxes” to make sure people end up learning what they need to know. Think Paris Island or KIPP schools.

It is important not to confuse “seeing high upfront signaling costs” with “the signaling model of education is essentially correct.” They sound like they should go together, but quite possibly they don’t.

Where I differ from Bryan Caplan’s *Labor Econ Versus the World*

One thing I liked about reading this book is I was able to narrow down my disagreements with Bryan to a smaller number of dimensions. And to be clear, I agree with a great deal of what is in this book, but that does not make for an interesting blog post. So let’s focus on where we differ. One point of disagreement surfaces when Bryan writes:

Tenet #6: Racial and gender discrimination remains a serious problem, and without government regulation, would still be rampant.

Critique: Unless government requires discrimination, market forces make it a marginal issue at most. Large group differences persist because groups differ largely in productivity.

I would instead stress that most of the inequity occurs upstream of labor markets, through the medium of culture. It is simply much harder to be born in the ghetto! I am fine with not calling this “discrimination,” and indeed I do not myself use the word that way. Still, it is a significant inequity, and it is at least an important a lesson about labor markets as what Bryan presents to you.

But you won’t find much consideration of it in Bryan’s book. The real problems in labor markets arise when “the cultural upstream” intersects with other social institutions in problematic ways. To give a simple example, Princeton kept Jews out for a long time, and that was not because of the government. Or Princeton voted to admit women only in 1969, again not the government. What about Major League Baseball before Jackie Robinson or even for a long while after? Much of Jim Crow was governmental, but so much of it wasn’t. There are many such examples, and I don’t see that Bryan deals with them. And they have materially affected both people’s lives and their labor market histories, covering many millions of lives, arguably billions.

Or, the Indian government takes some steps to remedy caste inequalities, but fundamentally the caste system remains, for whatever reasons. Again, this kind of cultural upstream isn’t much on Bryan’s radar screen. (I have another theory that this neglect of culture is because of Bryan’s unusual theory of free will, through which moral blame has to be assigned to individual choosers, but that will have to wait for another day!)

We can go beyond the discrimination topic and still see that Bryan is not paying enough attention to what is upstream of labor markets, or to how culture shapes human decisions.

Bryan for instance advocates open borders (for all countries?). I think that would be cultural and political suicide, most of all for smaller countries, but for the United States too. You would get fascism first, if anything. I do however favor boosting (pre-Covid) immigration flows into the United States by something like 3x. So in the broader scheme of things I am very pro-immigration. I just think there are cultural limits to what a polity can absorb at what speed.

If you consider Bryan on education, he believes most of higher education is signaling. In contrast, I see higher education as giving its recipients the proper cultural background to participate in labor markets at higher productivity levels. I once wrote an extensive blog post on this. That is how higher education can be productive, while most of your classes seem like a waste of time.

On poverty, Bryan puts forward a formula of a) finish high school, b) get a full time job, and c) get married before you have children. All good advice! But I find that to be nearly tautologous as an explanation of poverty. To me, the deeper and more important is why so many cultures have evolved to make those apparent “no brainer” choices so difficult for so many individuals. Again, I think Bryan is neglecting the cultural factors upstream of labor markets and in this case also marriage markets. One simple question is why some cultures don’t produce enough men worth marrying, but that is hardly the only issue on the table here.

More generally, I believe that once you incorporate these messy “cultural upstream” issues, much of labor economics becomes more complicated than Bryan wishes to acknowledge. Much more complicated.

I should stress that Bryan’s book is nonetheless a very good way to learn economic reasoning, and a wonderful tonic against a lot of the self-righteous, thoughtless mood affiliation you will see on labor markets, even coming from professional economists.

I will remind that you can buy Bryan’s book here, and at a very favorable price point.

Bryan Caplan’s stance on higher education policy

In my Warren post I wrote:

7. College free for all: Would wreck the relatively high quality of America’s state-run colleges and universities, which cover about 78 percent of all U.S. students and are the envy of other countries worldwide and furthermore a major source of American soft power. Makes sense only if you are a Caplanian on higher ed., and furthermore like student debt forgiveness this plan isn’t that egalitarian, as many of the neediest don’t finish high school, do not wish to start college, cannot finish college, or already reject near-free local options for higher education, typically involving community colleges.

Bryan wishes me to point out that he does not favor “free tuition for all,” and indeed that is true, as I can verify from years of discussion with him. Nonetheless I still believe such a policy would come closer to limiting educational signaling (by making so many schools worse and lowering the value of the signal) than would Bryan’s preferred policies toward higher ed.

SlateStarCodex and Caplan on ‘Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?’

SlateStarCodex, whose 2017 post on the cost disease was one of the motivations for our investigation, says Why Are the Prices so D*mn High (now available in print, ePub, and PDF) is “the best thing I’ve heard all year. It restores my faith in humanity.” I wouldn’t go that far.

SSC does have some lingering doubts and points to certain areas where the data isn’t clear and where we could have been clearer. I think this is inevitable. A lot has happened in the post World War II era. In dealing with very long run trends so much else is going on that answers will never be conclusive. It’s hard to see the signal in the noise. I think of the Baumol effect as something analogous to global warming. The tides come and go but the sea level is slowly rising.

In contrast, my friend Bryan Caplan is not happy. Bryan’s basic point is to argue, ‘look around at all the stupid ways in which the government prevents health care and education prices from falling. Of course, government is the explanation for higher prices.’ In point of fact, I agree with many of Bryan’s points. Bryan says, for example, that immigration would lower health care prices. Indeed it would. (Aside: it does seem odd for Bryan to argue that if K-12 education were privately funded schools would not continue their insane practice of requiring primary school teachers to have B.A.s when in fact, as Bryan knows, credentialism has occurred throughout the economy)

The problem with Bryan’s critiques is that they miss what we are trying to explain which is why some prices have risen while others have fallen. Immigration would indeed lower health care prices but it would also lower the price of automobiles leaving the net difference unexplained. Bryan, the armchair economist, has a simple syllogism, regulation increases prices, education is regulated, therefore regulation explains higher education prices. The problem is that most industries are regulated. Think about the regulations that govern the manufacture of automobiles. Why do all modern automobiles look the same? As Car and Driver puts it:

In our hyperregulated modern world, the government dictates nearly every aspect of car design, from the size and color of the exterior lighting elements to how sharp the creases stamped into sheet metal can be.

(See Jeffrey Tucker for more). And that’s just design regulation. There are also environmental regulations (e.g. ethanol, catalytic converters, CAFE etc.), engine regulations, made in America regulations, not to mention all the regulations on the inputs like steel and coal. The government even regulates how cars can be sold, preventing Tesla from selling direct to the public! When you put all these regulations together it’s not at all obvious that there is more regulation in education than in auto manufacturing. Indeed, since the major increase in regulation since the 1970s has been in environmental regulation, which impacts manufacturing more than services, it seems plausible that regulation has increased more for auto manufacturing.

As an empirical economist, I am interested in testable hypotheses. A testable hypothesis is that the industries with the biggest increases in regulation have seen the biggest increases in prices over time. Yet, when we test that hypothesis as best we can it appears to be false. Remember, this does not mean that regulation doesn’t increase prices! It can and probably does it’s just that regulation is not the explanation for the differences in prices we see across industries. (Note also that Bryan argues that you don’t need increasing regulation to explain increasing prices, which is true, but I still need a testable hypotheses not an unfalsifiable claim.)

So by all means let’s deregulate, but don’t expect 70+ year price trends to reverse until robots and AI start improving productivity in services faster than in manufacturing.

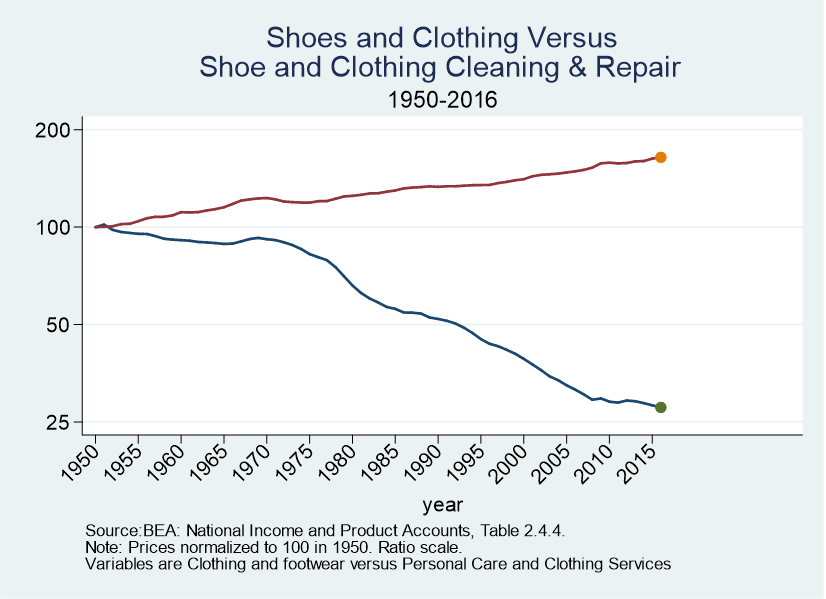

Let me close with this. What I found most convincing about the Baumol effect is consilience. Here, for example, are two figures which did not make the book. The first shows car prices versus car repair prices. The second shows shoe and clothing prices versus shoe repair, tailors, dry cleaners and hair styling. In both cases, the goods price is way down and the service price is up. The Baumol effect offers a unifying account of trends such as this across many different industries. Other theories tend to be ad hoc, false, or unfalsifiable.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

My Conversation with Bryan Caplan

Bryan was in top form, I can’t recall hearing him being more interesting or persuasive. Here is the audio and text. We talked about whether any single paper is good enough, the autodidact’s curse, the philosopher who most influenced Bryan, the case against education, the Straussian reading of Bryan, effective altruism, Socrates, Larry David, where to live in 527 A.D., the charm of Richard Wagner, and much more. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: You love Tolstoy, right?

CAPLAN: Yeah. You love Tolstoy because here’s a guy who not only has this encyclopedic knowledge of human beings — you say he knows human nature. Tolstoy knows human natures. He realizes that there are hundreds of kinds of people, and like an entomologist, he has the patience to study each kind on its own terms.

Tolstoy, you read it: “There are 17 kinds of little old ladies. This was the 13th kind. This was the kind that’s very interested in what you’re eating but doesn’t wish to hear about your romance, which will be contrasted with the seventh kind which has exactly the opposite preferences.” That’s what’s to me so great about Tolstoy.

Here is one of my questions:

What’s the fundamental feature in Bryan Caplan–think that has made you, unlike most other nerds, so much more interested in Stalin than science fiction?

Here is another exchange:

COWEN: You think, in our society in general, this action bias infests everything? Or is there some reason why it’s drawn like a magnet to education?

CAPLAN: Action bias primarily drives government. For individuals, I think even there there’s some action bias. But nevertheless, for the individual, there is the cost of just going and trying something that’s not very likely to succeed, and the connection with the failure and disappointment, and a lot of things don’t work out.

There’s a lot of people who would like to start their own business, but they don’t try because they have some sense that it’s really hard.

What I see in government is, there isn’t the same kind of filter, which is a big part of my work in general in politics. You don’t have the same kind of personal disincentives against doing things that sound good but actually don’t work out very well in practice.

Probably even bigger than action bias is actually what psychologists call social desirability bias: just doing things that sound good whether or not they actually work very well and not really asking hard questions about whether things that sound good will work out very well in practice.

I also present what I think are the three strongest arguments against Bryan’s “education is mostly signaling” argument — decide for yourself how good his answers are.

And:

COWEN: …Parenting and schooling in your take don’t matter so much. Something is changing these [norms] that is mostly not parenting and not schooling. And they are changing quite a bit, right?

CAPLAN: Yes.

COWEN: Is it like all technology? Is the secret reading of Bryan Caplan that you’re a technological determinist?

CAPLAN: I don’t think so. In general, not a determinist of any kind.

COWEN: I was teasing about that.

And last but not least:

CAPLAN: …When someone gets angry at Robin, this is what actually outrages me. I just want to say, “Look, to get angry at Robin is like getting angry at baby Jesus.” He’s just a symbol and embodiment of innocence and decency. For someone to get angry at someone who just wants to learn . . .

COWEN: And when they get mad at me?

CAPLAN: Eh, I understand that.

Hail Bryan Caplan! Again here is the link, and of course you should buy his book The Case Against Education.

Signaling and the evolution of female wages

How do partisans of the signaling model of education explain female wage growth over the last few decades? It’s easy for the human capital theory: female education went up and so did female productivity (plus discrimination fell, but let’s put that aside for now).

But if those women were just signaling, their productivities are about the same and yet their wages are way higher. Are they now massively overpaid? That hardly seems possible — when will the en masse firing begin?

Alternatively, perhaps the women were considerably underpaid in 1963, because their lack of interest in educational signaling branded them as lower quality workers. (Again, this has to be an effect net of discrimination.) But why would that have been a rational inference for employers to make? If a woman didn’t go to college or graduate school back in 1963, there were plenty of obvious sociological reasons why not, and it didn’t much signal low intelligence or low conscientiousness. It shouldn’t have lowered wages, not in the signaling model. So in 1963 there was a discrimination-based underpayment, but it is hard to argue for a signaling-based underpayment to women as a class.

You also might think that female wages have gone up since 1963 because women have been socialized to desire work and money more. But if that socialization raises productivity, it still won’t support a signaling story, which treats productivity as fixed due to type. Furthermore then the door is open for socialization theories of education, even if college is not the only source of socialization.

So why then have net-of-discrimination female wages gone up so much, if not for the human capital story?

You will note that the signaling theory seems most plausible as an explanation of what happens right after people get out of college, and thus it appeals to many students and also to some academics. Signaling theories of wages are least plausible as they try to explain broad patterns of wage movements over time, and then you must bring in human capital considerations. In similar fashion, signaling theories won’t explain the relative wage stagnation since 1999 and many other longer-term puzzles; they just don’t play in this arena.

Here are some data on female wages and labor supply over this period.

Addendum: Bryan Caplan refers me to this piece of his on related issues. And here is my Econ Duel with Alex on education and signaling.

Score one for the signaling model of education

In the new AER there is a paper by Melvin Stephens Jr. and Dou-Yan Yang, the abstract is this:

Causal estimates of the benefits of increased schooling using US state schooling laws as instruments typically rely on specifications which assume common trends across states in the factors affecting different birth cohorts. Differential changes across states during this period, such as relative school quality improvements, suggest that this assumption may fail to hold. Across a number of outcomes including wages, unemployment, and divorce, we find that statistically significant causal estimates become insignificant and, in many instances, wrong-signed when allowing year of birth effects to vary across regions.

In other words, those semi-natural experiments for the return to education, when some regions move with extra doses of compulsory schooling before others and we estimate differential wage effects, maybe don’t show as much as we used to think. As I’ve remarked to Bryan Caplan, if there is a criticism of a famous or politically correct result (or better yet both) getting published in the AER, you can up your Bayesian priors on that criticism being on the mark.

There are ungated copies of the paper here.

How many bankruptcies to come in higher education?

Bryan Caplan doubts that on-line education will lead to many bankruptcies in higher education. To provide a contrasting point of view, I see the landscape as follows:

1. The absolute wages of college graduates have been falling for over a decade, even though the relative premium over “no college degree” is robust. Still, absolute wages do determine the long-term viability of any revenue model. And note that a pretty big chunk of the relative college wage premium is captured through post-secondary education only.

2. The “debt bubble” behind a lot of recent higher education expansion won’t be repeated anytime soon.

3. A large number of institutions in the top one hundred will move to a hybrid on-line model for a third or so of their classes and they will do so gradually, without seriously disrupting norms of conformity or eliminating campus life. In fact this will become the new conformity and furthermore through time-shifting it may increase the quantity and joy of drunken parties and campus orgies. Eventually these on-line classes will be sold for credit to outside students. Some top schools will sell credits in this manner, even if the more exclusive Harvard and Princeton do not. Many lesser schools will lose a third or so of their current tuition revenue stream. Note that the prices for these on-line credits, even if hybrid, will likely be much lower, plus lesser schools lose revenue to the schools better at designing on-line content.

4. Some state governors will try to put out a supposedly semi-passable degree from their state schools for 10k a year, with some on-line components of course. That will put price and revenue pressure on many other schools.

So let’s say you are Trinity International University, in Deerfield, Illinois, 1,265 students, nominal tuition about 26k. I had never heard of that place before doing a quick search through U.S. News rankings. Still, it is rated in the second tier. Will it survive? Maybe their Evangelical orientation will push them through. Maybe it will sink to 500 students.

How about Lynn University, in Florida, also second tier, nominal tuition listed as 32k? 1,619 students, but how many by say 2032?

I don’t think bankruptcy, literally interpreted, is the likely legal outcome (for one thing, these schools probably don’t have enough debt for bankruptcy law to be relevant). Still, I think it is quite possible that one hundred or more schools in the U.S. News rankings will find their enrollments or at least their tuition revenue streams cut in half or more within twenty years. They will be shells of their former selves, though on-line education might not even be their major economic challenge. It will be one of three or four major whammies facing them. Higher education as a general practice of course still will thrive, as will community colleges.

One key question is whether on-line education will encourage consolidation or not. Under one vision, on-line offerings shore up the smaller schools, because you can go to them for the atmosphere while taking German III purely on-line. (Even then, they survive but the revenue stream takes a huge whack.) Under another vision, on-line — for most students — works best in hybrid form, mixed with various face-to-face forms, and the larger schools will have a much easier time getting this off the ground in a workable manner.

Two additional comments on Bryan’s post. First, he thinks that for on-line education “…the dollars of venture capital raised are laughable.” Yet keep in mind that the major players are or can be backed by the endowments of the top universities. In any case, why raise extra money before you are able to spend it? If these on-line efforts get any traction at all, the funding and lines of credit will be there.

Second, advocates of the relevance of the signaling model should be relatively optimistic about on-line education. Because it is hard to pay attention in the on-line schoolhouse, it provides an especially potent signal! And you always face the temptation to upgrade your signal by subbing in some Top School on-line credits for some of your Podunk University credits. (Sooner or later Podunk will have to accept such credits.) Social pressures for conformity will encourage rather than stop that trend. On the other hand, if you subscribe to a learning model for higher education, there are some very legitimate questions as to how well the on-line product can teach you what you need to know, at least for people with some fairly wide variety of learning styles.

Conformity pressures and signaling may militate against the “stay at home all day” forms of on-line education, but not against on-line education more generally, in fact quite the contrary. In my view Bryan is underestimating the economic problems to be faced by a wide range of colleges and universities, and putting up a not very plausible model of non-conformist on-line ed as the major threat.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments.

The shift to on-line education can happen gradually and easily

I left the following comment on Bryan Caplan’s blog post:

You don’t need to overturn all convention. The top schools could shift at the margin, as they have many times in the past, and suddenly the conformist thing to do is to have ?? percent of your classes be on-line, and so on. In virtually any other context you would see the flexibility of the market here! No major credentials need to collapse, if it turns out that cannot happen easily.

This is a phantom issue, raised by many people but not thought through deeply enough. Markets convexify (sometimes).

It is fine to argue “on-line education is not in fact more efficient.” It is much harder to argue “if it is efficient, conformity pressures will keep it out of the market.” Don’t confuse the former case with the latter.

When are signaling and human capital theories of education observationally equivalent?

Going as far back as Andrew Weiss’s survey paper, there are various attempts to argue that the two theories make the same predictions about earnings and education. A randomly elevated individual will earn more money but is this from having learned more or from being pooled with a more productive set of peers?

To explore this, let’s pursue the very good question asked by Bryan Caplan:

Our story begins with a 22-year-old high school graduate with a B average. He knows an unscrupulous nerd who can hack into Harvard’s central computer and give him a fake diploma, complete with transcript. In the U.S. labor market, what is the present discounted value of that fake diploma?

If he can fake a good interview (a big if, but let’s say), and if certification from recommenders is not important in the chosen sector (another big if), he may get a Harvard-quality job for his first placement. If you believe in the signaling theory, however, his marginal product is fairly low, much lower than the wage he will be paid. They will fire him. He’ll come out a bit ahead, if he is not too demoralized, but within a few years he will be paid his marginal product.

In most jobs they figure out your productivity within two or three months after training, if not sooner.

In a one-shot static setting, signaling and human capital theories might have the same empirical implications because the learning and pooling effects can produce similar links between education and wages (again assuming someone can fake an interview). But not over time and of course the wage dispersion for an educational cohort does very much increase with time. The workers don’t keep on receiving their “average marginal product” for very long.

Do not be tricked by those who serve up one-period examples to establish the empirical equivalence of signaling and human capital theories!

To tie this back to the academic literature, if IV-elevated workers enjoy an enduring wage effect comparable to that of the other degreed workers, you should conclude they learned something comparable at school unless you wish to spin an elaborate and enduring W > MP story.

Addendum: There is a less drastic scenario than the one outlined by Bryan. Let’s say there are fourteen classes of workers and a class nine worker is randomly elevated to class seven credentials. He might use that momentary good fortune to learn from smarter peers, work hard to establish a foothold, and so on. His lifetime earnings might end up as roughly those of other class seven workers, despite being of initial type nine. The higher earnings are still based on learning effects (not mainly pooling), though pooling gave that worker temporary access to some new learning and advancement opportunities. In most regards this works like the learning model, not the pooling model, although the period of learning extends beyond schooling narrowly construed.

More on the returns to education

First, apologies to Arnold, I missed his post when traveling and so he does discuss natural experiments, contrary to my previous claim about EconLog bloggers. That said, I’m not so happy with his analysis. He’s taking a few of the papers he sees as the weakest and he explains why they are weak. I would rather he dissects the strongest pieces and compares them to the strongest pieces, using natural experiments, showing very low rates of return to education. The Joshua Angrist papers (often with Alan Krueger) for instance are quite sophisticated and do not run afoul of Arnold’s objections. In works such as this (later versions seem to be gated), Angrist and Krueger perform exactly the natural experiment which Arnold requests and they find high (marginal) returns to education. Or see this piece by Card.

Here is Bryan’s response to my post. Focus on his #2, which is the crux of the matter:. He cites the signaling motives for education and concludes: “Here, the evidence Tyler cites is simply irrelevant.” This is simply not true and indeed these papers are obsessed with distinguishing learning effects from preexisting human capital differences. That is what these papers are, so to speak. In that context, “ability bias” in the estimates doesn’t seem to be very large, see for instance the Angrist or Card pieces linked to above. This paper surveys some of the “adjusting for ability bias” literature; it is considered quite “pessimistic” (allows for a good deal of signaling, in Caplan’s terminology) and still it finds a positive five percent a year real productivity gain from an extra year of schooling.

What’s striking about the work surveyed by Card is how many different methods are used and how consistent their results are. You can knock down any one of them (“are identical twins really identical?, etc.), but at the end of the day which are the pieces — using natural or field experiments — standing on the other side of the scale? The Card results are also consistent with theory, namely that models which emphasize signaling imply large unrealized gains from trade; it’s not that hard for an employer to administer an implicit IQ test as Google and Microsoft do all the time. As a separate (and here undocumented) point, I would argue the Angrist and Card results are consistent with the bulk of results from sociological and anthropological investigations.

There really does seem to be a professional consensus. Maybe it’s wrong, and/or dominated by biased pro-education specialists, but I’m not seeing very strong arguments against it. For the time being at least, I don’t see that there is much anywhere else to go with one’s beliefs. If Arnold or Bryan (or David) suggests a good paper with a natural experiment showing a low marginal ROR for education, I am happy to read the paper and report back and compare it to the preponderance of evidence on the other side.

The real puzzle is how large measured marginal returns to education are consistent with the continuing observed failures of the American educational system. Why does the low-hanging fruit persist or is it low-hanging at all? The traditional liberal view is that further educational subsidies are needed, but a possible alternative is that some people simply do not wish to step across to the other side of the divide to a “better life,” at least as defined by middle class values and income statistics. Or is there some other hypothesis? Whichever way you cut it, a big improvement in this area does not seem about to happen and arguably we are moving in the opposite direction. Whatever gains are there “in the data,” we don’t seem able or willing to capture them.

My debate with Bryan Caplan on education

Bryan writes:

The other day, Tyler Cowen challenged me to name any country that I consider under-educated. None came to mind. While there may be a country on earth where government doesn't on net subsidize education, I don't know of any.

…This analysis holds in the Third World as well as the First. The fact that Nigerians and Bolivians don't spend more of their hard-earned money on education is a solid free-market reason to conclude that additional education would be a waste of their money.

I would first note that many parts of many poor countries, today, receive de facto zero government subsidies for education. Or put aside the issue of government provision and ask if you were a missionary and could inculcate a few norms what would they be? Many regions – in particular Latin America — are undereducated for their levels of per capita income. I view this as a serious cultural failing, most of all in terms of its collective social impact. In contrast, Kerala, India is very intensely educated for its income level and that brings some well-known benefits in terms of social indicators and quality of life.

If I think of the Mexican village where I have done field work, the education sector "works" as follows. No one in the village is capable of teaching writing, reading, and arithmetic. A paid outsider is supposed to man the school, but very often that person never appears, even though he continues to be paid. Children do have enough leisure time to take in schooling, when it is available. I am told that most of the teachers are bad, when they do appear. You can get your children (somewhat) educated by leaving the village altogether, and of course some people do this. In the last ten years, satellite television suddenly has become the major educator in the village, helping the villagers learn Spanish (Nahuatl is the indigenous language), history, world affairs, some science from nature shows, and telenovela customs. The villagers seem eager to learn, now that it is possible.

That scenario is only one data point but it is very different than the "demonstrated preference" model which Bryan is suggesting. Bolivia and Nigeria are much poorer countries yet and they have dysfunctional educational sectors as well, especially in rural areas. Bad roads are a major problem for "school choice" in these regions, just as they are a major problem for the importation of teachers.

A simple model is that underinvestment in infrastructure results in a high shadow value for marginal increments of education. Model = high fixed costs, liquidity constraints if you wish, high shadow values for lots of goods and services, toss in social externalities to raise the size of the distortion. I read Bryan as focusing on "the fixity of the fixed costs" and claiming it is too costly to get the service through, relative to return.

Of course Bryan favors rising wealth and falling fixed costs, as do I. But in the meantime he also should admit that a) education "parachuted" in from outside can have a high marginal return, b) collectively stronger pro-education norms raise demand and can alleviate the high fixed costs problem, c) there are big external benefits, some operating through the education channel, to lowering the fixed costs, d) stronger pro-education norms put a region closer to a "big breakthrough" and weaker education norms do the opposite, and e) a-d still impliy "too little education" is the correct judgment. On b), some evangelical groups in Latin America do seem to have stronger pro-education norms in their converts and it appears to be much better for the children of these families and no I'm not going to buy any response which ascribes the whole effect to selection.

I believe that Bryan's own work on voting suggests significant positive social external benefits from education, although he is not happy with how I characterize his view here. I also believe his views on children suggest strong peer effects across children (parental effort doesn't matter so much in his model and the rest of the influence has to come from somewhere), though in conversation I am again not sure he accepts this characterization.

I consider most countries in today's world to be undereducated.

Signaling models are important but they are not the only effect and of course a lot of signaling is welfare-improving for reasons of screening and sorting and character reenforcement. The traditional story of high social returns to education is supported by evidence from a wide variety of different fields and methods, including cross-sectional growth models, labor economics, political science, public opinion research, anthropology, education research, and much more. You can knock some of this down by stressing the endogeneity of education, but at the end of the day the pile of evidence, and the diversity of its directions, is simply too overwhelming.

Online Education and the Market for Superstar Teachers

I have argued that universities will move to a superstar market for teachers in which the very best teachers use on-line instruction and TAs to teach thousands of students at many different universities. The full online model is not here yet but I see an increasing amount of evidence for the superstar model of teaching. At GMU some of our best teachers are being recruited by other universities with very attractive offers and some of our most highly placed students have earned their positions through excellence in teaching rather than through the more traditional route of research.

I do not think GMU is unique in this regard–my anecdotal evidence is that the market for professors is rewarding great teachers with higher wages and higher placements than in earlier years.

The online aspect, which enhances the market for superstars, is also growing. Here from a piece on online education in Fast Company are a few nuggets on for-profit colleges which have moved online more quickly than the non-profits.

Today, for-profit colleges enroll 9% of all students, many of them in online programs. It's safe to assume they'll soon have many more….for-profits are the only sector significantly expanding enrollment — up 17% since the start of the recession in 2008….the University of Phoenix, which with 420,000 students is the largest university in North America.

Interesting explanation for why for-profits still lag:

Since there are no generally accepted measurements of learning in traditional higher education, the proxy for the value of a diploma on the job market is prestige. Rankings like those of U.S. News & World Report depend on reputation; spending per student, including spending on research; and selectivity — a measure of inputs, not outputs. On all these measures, for-profits come up short.

But how long can we expect the inability to measure to protect academia when there are big profits to be made? Robin Hanson would argue that most of what is going on is signaling, i.e. that prestige is what is being bought and sold and not prestige as a proxy for some other measure of quality. No doubt there is some truth to that but there are plenty of fields, dentistry, engineering, computer science where measurable quality matters as well.

It's true that the university equilibrium has lasted a long time but that doesn't mean it can't break down very quickly.

Addendum: Bryan Caplan laughs but Arnold Kling has the right idea.

The Parent Trap–Review of Hilger

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Nate Hilger has written a brave book. Almost everyone will find something to hate about The Parent Trap. Indeed, I hated parts of it. Yet Hilger is willing to say truths that are often not said and for that I would rather applaud than cancel.

Hilger argues that the problems of poverty, pathology and inequality that bedevil the United States are not primarily due to poor schools, discrimination, or low incomes per se. The primary cause is parents: parents who are unable to teach their children the skills that are necessary to succeed in the modern world. Since parents can’t teach the necessary skills, Hilger calls for the state to take their place with a dramatic expansion of not just child care but collective parenting.

Let’s unpack some details. Begin with schooling. It’s very common to bemoan the state of schools in the “inner city” or to complain about “local financing” which supposedly guarantees that poor counties will have underfunded schools. All of this, however, is decades out-of-date.

A hundred years ago there really were massive public-school resource gaps by class and race. These days, however, state and federal spending play a larger role than local property tax revenue and distribute educational resources more progressively….In fact, when we include federal aid, 42 states spent more on poor school districts than on rich school districts in 2012. The same pattern holds between schools within districts

….The highest spending districts are large urban centers such as New York City, Boston and Baltimore. These cities spend large sums to educate rich and poor children alike. p. 10-11

Hilger is correct. No matter what you saw on The Wire, Baltimore spends more than sixteen thousand dollars per student, among the highest in the nation in large school districts and above average for the nation as a whole. Public schools are quite egalitarian in funding with any bias running towards more funding for poorer districts.

Schools, Hilger writes are “actually the smallest and most equalizing part of a much larger skill-building system.” The real problem, says Hilger, are parents.

But what about discrimination? When it comes to wage discrimination, Hilger is brutally honest:

If we compare individuals with similar cognitive test scores, Black college graduates earn higher wages than white college graduates. Studies that don’t control for test score differences but examine earnings gaps within specific professions—lawyers, physicians, nurses, engineers, scientists—tend to find Black workers earn zero to 10 percent less than white workers. These gaps could reflect discrimination, unmeasured skill differences, or other factors such as geography. In any case, such gaps are small compared to the 50 percent overall Black-white earnings gap and reinforce the idea that closing skills gaps would go a long way toward closing income gaps.

Hilger argues that racism does play an important role in explaining Black-white wage differentials but it’s the historical racism that made black parents less skilled and less able to pass on skills to their children. In the twentieth century, Asians, Hilger argues, were discriminated against in the United States at least much as Black Americans. But the Asians that came to the United States had high skills while the legacy of slavery meant that Black Americans began with low skills. Asians, therefore, were better able to overcome discrimination. The success of Nigerians and Jamaican immigrants in the United States also speaks to this point. (Long time readers may recall that in 2016 I dubbed Hilger’s paper on Asian Americans and Black Americans the Politically Incorrect Paper of the Year .)

Parental investment is surely important but Hilger overstates his case. He writes as if poorer parents have neither the abilities nor the time to teach their children while richer, better educated parents simply invest lots of hours and money imbuing their children with skills:

…the enormous variation in parents’ own academic skills has big implications for kids because we also demand that parents try to be tutors. During normal times, parents in America spend an average of six hours per week helping—or trying to help—their kids with school work. Six hours per week is more than K12 math and English teachers get with children…good tutoring by parents for six hours a week, every week, year after year of childhood could raise children’s future earnings by as much as $300,000.

The data on the effectiveness of SAT test-prep suggests that these efforts are not nearly so effective as Hilger argues. The parental investment story also doesn’t fit my experience. I didn’t spend six hours a week helping my kids with their homework. I doubt most parents do. I simply assumed my kids would do their work. I do recall that we signed my kids up for tutoring at Kumon, the Japanese math education center. My kids would complain bitterly when we took them for drill on the weekend. It was mostly filling out rote forms and my kids would hide or bury their drill sheets so we were always behind. Driving my kids to the Kumon center, monitoring them. and forcing them to do the work when they rebelled like longshoreman on work-to-rule was time consuming and it was ruining our weekends. I felt guilty, but after a while, my wife and I gave up. Today one of my sons is a civil engineer and the other is a math and economics major at UVA.

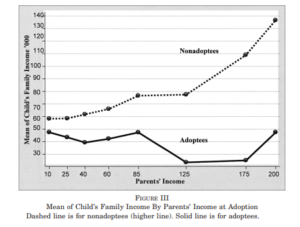

Hilger has an answer to this line of objection, or at least he says he does, but to my mind it’s a very odd answer. He argues, relying heavily on Sacerdote, that adoption studies show that more skilled parents result in more skilled kids. I find that answer odd because my reading of Sacerdote is that the effect of parents are small after you control for genetics—this is, as Hilger acknowledges, the conventional wisdom among psychologists. (See Caplan for an excellent review of the literature). It is true that Sacerdote plays up the effect of parents, but it looks small to me. Here is the effect of the adopted mother’s maternal education on the child’s education.

As you can see there is an effect but it is almost all from the mother going from having less than a high school education to graduating high school (11 to 12 years). In contrast, the mother can move from graduating high school to having a PhD and there is very little change in the education level of an adoptee. Note, however, that the effect on non-adoptees, i.e. biological children, is much larger throughout the entire range which suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

I am not surprised that there is some effect of parental education on child’s education because going to college is in part a cultural issue. Parents can influence cultural aspects of their children’s identity such as whether a child grows up up nominally Catholic, Mormon, or Hindu but they have relatively little effect on child religiosity, let alone personality or IQ. I think that a large fraction of the college wage premium is signaling (50% is a moderate estimate, Caplan thinks 90% is closer to the truth), so I am also not overly excited about college attendance as a marker of success.

The effect of parental income on the income of child adoptees is even more dramatic than on education—which is to say negligible. The income of the adopted parents has zero effect (!) on child’s income even as parent’s income varies by a factor of 20! The only correlation is with non-adoptee income—which again suggests the influence of nature not nurture.

At this point in the book, it was almost inevitable that we were going to get yet another paean to the Perry Preschool Project and indeed Hilger waxes enthusiastically about Perry. Seriously? The Perry Preschool project started in the 1960s and had just 123 participants (58 in treatment and 65 in control!). There are more papers about the Perry Preschool project than there were participants. I am jaded.

Aside from the small sample size, the project had imperfect randomization and missing data and most importantly limited external validity. The Perry Preschool project treated a small group of disadvantaged African American children with low-IQs (IQs of 70-85 were part of the selection criteria). The treatment is usually described as “active learning pre-school” but it was more intrusive than that. Every week counselors would go to the homes of the kids to teach the parents (mostly mothers) how to raise their children. The training was important to the program. Indeed, Hilger notes, without sense of irony, that “facilitating greater skill growth in low-income children was so complicated that it required home visitors with advanced postsecondary degrees.” (p. 89). And what were the results?

The results were good! (Heckman et al. 2010, Belfield et al. 2006). But in the popular literature the impression one gets is that the program took a bunch of disadvantaged kids and helped them read and write, making them more middle-class and successful. Some of that happened but the big gains actually happened because the participants, especially the boys, were so socially dangerous and destructive that even a bit of normalization made life substantially better for everyone else. In particular 82% of the treated group of 33 males had been arrested by age 40, including for one murder, 4 rapes, 8 robberies, 11 assaults and 14 burglaries. The control group were worse. In the control group of 39 males there were 2 murders. Indeed the reduction of one murder in the treatment group accounts for a significant benefit of the entire Perry PreSchool project.

Hilger, to his credit, is reasonably clear that what is really needed is an intensive program for disadvantaged African Americans, especially males. In a stunning sentence he writes:

The more we rely on families rather than professionals to build skills in children, the tighter we link people’s current prospects to the prospects of their ancestors. p. 134

But he soon forgets or papers over the context of the Perry Preschool project and like everyone else in the literature uses this to support a national program for which there is no external validity. It’s hard to believe, given the lack of external validity, but Heckman et al. (2010) only exagerate mildly when they write:

The economic case for expanding preschool education for disadvantaged children is largely based on evidence from the HighScope Perry Preschool Program…

Hilger’s case for the difficulty of parenting is well taken—the FAFSA was a nightmare that taxed two PhDs in my family. But the bottom line is that most parents do just fine. Moreover, it’s shocking that in recounting the difficulties of parenting Hilger says hardly one word about an obvious factor which makes parenting more than twice as hard. Namely, single parenting. I was a single parent. Once for a whole week. Don’t do it. Get married, stay married. Perhaps Hilger didn’t want to appear to be too conservative.

Instead of recommending marriage and small targeted programs and more experiments, Hilger goes full Plato.

What would it look like if we [asked]…less not more of parents? It would look like professional experts managing more than the meagre 10 percent of children’s time currently managed by our public K12 system—much more. p. 184

And why should we do this? Because we are all part slaves and part slave-owners on a giant collective farm:

As fellow citizens who benefit from tax revenue, we all—even those of us without children—collectively own about 30 percent of any additional income other people’s children wind up earning. p. 197

Ugh. We own ourselves, not one another. Society isn’t about maximizing the collective it’s about free individuals coming together to produce rules so that we can enjoy the benefits of collective action while still living in a diverse society that respects individual rights, beliefs, and ways of living.

I told you I hated parts of The Parent Trap but Hilger has written an interesting and challenging book and he is mostly right that neither schooling nor labor market discrimination play a major role in the black-white wage gap. Hilger is probably also right that we spend too much on the elderly relative to the young. The idea of greater state involvement in the raising of children is on the table today in a way it hasn’t been for some time. See also Dana Susskind’s recent book Parent Nation. Changes on the margin may be warranted. Nevertheless, I stand with Aristotle and not Plato in thinking that raising children is better done by parents than by the state.