Results for “corporate profits” 98 found

Are American corporate profits really so high?

Notice that if a U.S. corporation earns a profit from affiliate operations abroad, the profit will be added to the numerator of CPATAX/GDP, but the costs will not be added to the denominator, as they should be in a “profit margin” analysis. Those costs, the compensation that the U.S. corporation pays to the entire foreign value-added chain–the workers, supervisors, suppliers, contractors, advertisers, and so on–are not part of U.S. GDP. They are a part of the GDP of other countries. Additionally, the profit that accrues to the U.S. corporation will not be added to the denominator, as it should be–again, it was not earned from operations inside the United States. In effect, nothing will be added to the denominator, even though profit was added to the numerator.

General Motors (GM) operates numerous plants in China. Suppose that one of these plants produces and sells one extra car. The profit will be added to CPATAX–a U.S. resident corporation, through its foreign affiliate, has earned money. But the wages and salaries paid to the workers and supervisors at the plant, and the compensation paid to the domestic suppliers, advertisers, contractors, and so on, will not be added to GDP, because the activities did not take place inside the United States. They took place in China, and therefore they belong to Chinese GDP. So, in effect, CPATAX/GDP will increase as if the sale entailed a 100% profit margin–actually, an infinite profit margin. Positive profit on a revenue of zero.

Here is much more, with many visuals and further details at the link, including a treatment of how to measure corporate profits accurately.

For the pointer, I thank @IronEconomist.

Why have corporate profits been high?

Jeremy Siegel reports:

…David Bianco, chief equity strategist at Deutsche Bank, has shown that most of the margin expansion over the past 15 years has come from two factors: the increased proportion of foreign profits, which have higher margins because of lower corporate tax rates; and the increased weight of the technology sector in the S&P 500 index, a sector that usually carries the highest profit margins.

Higher profit margins also result from stronger balance sheets. The Federal Reserve reports that since 1996, the ratio of corporate liquid assets to short-term liabilities has nearly doubled, and the proportion of credit market debt that is long term has increased to almost 80 per cent from about 50 per cent. This means many companies have locked in the recent record low interest rates and will be much less sensitive to any future increase in rates, keeping margins high.

Are corporate profits a sinkhole for purchasing power?

That seems to be Krugman’s argument here, and here, excerpt:

So corporations are taking a much bigger slice of total income — and are showing little inclination either to redistribute that slice back to investors or to invest it in new equipment, software, etc.. Instead, they’re accumulating piles of cash.

I am confused by this argument. I would understand it (though not quite accept it) if corporations were stashing currency in the cupboard. Instead, it seems that large corporations invest the money as quickly as possible. It can be put in the bank and then lent out. It can purchase commercial paper, which boosts investment.

Maybe you are less impressed if say Apple buys T-Bills, but still the funds are recirculated quickly to other investors. This may not end in a dazzling burst of growth, but there is no unique problem associated with the first round of where the funds come from. If there is a problem, it is because no one sees especially attractive investment opportunities in great quantity. (To the extent there is a real desire to invest, the Coase theorem will get the money there.) That’s a problem at varying levels of corporate profits and some call it The Great Stagnation.

The same response holds if Apple puts the money into banks which earn IOR at the Fed and the money “simply sits there.” The corporations are not withholding this money from the loanable funds market but rather, to the extent there is a problem, the loanable funds market does not know how to invest it at a sufficiently high ROR.

If anything, large corporations are more likely to diversify out of the U.S. dollar, which could boost our exports a bit, a plus for a Keynesian or liquidity trap story.

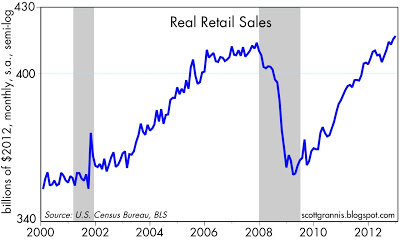

When one looks at the components of aggregate demand, retail sales, after a large and obvious hit, seem to be recovering. They are up 4.7% from Dec. 2011 to Dec. 2012 (pdf). If that is what a sinkhole looks like, as I said I am puzzled:

Here is the story of business investment minus corporate profits and that series doesn’t impress me (Krugman seems to think it is doing OK). The trickier variable of net investment you will find here and that looks worse.

By the way, Fritz Machlup considered related arguments in his 1940 book.

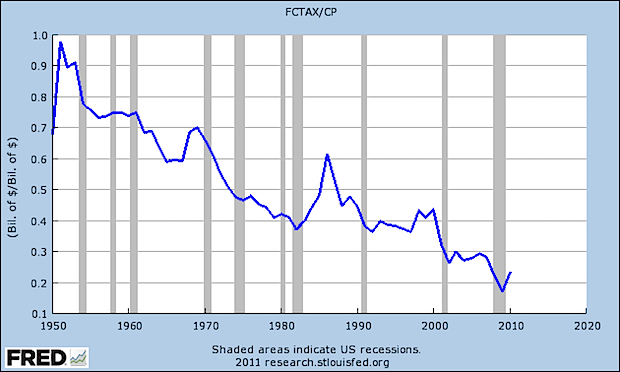

Corporate income tax as a share of corporate profits

That is from Felix Salmon, or try this one, namely corporate income tax as a percentage of gdp:

I still think the corporate rate should be zero, but the corporate income tax is one of the most commonly over-villainized institutions by the intelligent Right.

Addendum: Kevin Drum offers up a related chart.

Professors on Corporate Boards Increase Profits

SSRN: Directors from academia served on the boards of around 40% of S&P 1,500 firms over the 1998-2011 period. This paper investigates the effects of academic directors on corporate governance and firm performance. We find that companies with directors from academia are associated with higher performance and this relation is driven by professors without administrative jobs. We also find that academic directors play an important governance role through their advising and monitoring functions. Specifically, our results show that the presence of academic directors is associated with higher acquisition performance, higher number of patents and citations, higher stock price informativeness, lower discretionary accruals, lower CEO compensation, and higher CEO forced turnover-performance sensitivity. Overall, our results provide supportive evidence that academic directors are valuable advisors and effective monitors and that, in general, firms benefit from having academic directors.

I blogged an earlier version of this paper several years ago but the result continues to hold with five more years of data so you know who to call.

Hat tip: Professor Bainbridge.

Academics on Corporate Boards Increase Profits

Francis, Hasan and Wu have produced a paper with important results!

Directors from academia served on the boards of more than one third of S&P 1,500 firms over the 1998-2006 period. This paper investigates the effects of academic directors on corporate governance and firm performance. We find that companies with directors from academia are associated with higher performance. In addition, we find that professors without administrative jobs drive the positive relation between academic directors and firm performance. We also show that professors’ educational backgrounds affect the identified relationship. For example, academic directors with business-related degrees have the most positive impacts on firm performance among all the academic fields considered in our regressions. Furthermore, we show that academic directors play an important governance role through their monitoring and advising functions. Specifically, we find that the presence of academic directors is associated with higher acquisition performance, higher number of patents, higher stock price informativeness, lower discretionary accruals, lower CEO compensation, and higher CEO turnover-performance sensitivity. Overall, our results provide supportive evidence that academic directors are effective monitors and valuable advisors, and that firms benefit from academic directors.

CEO’s of large firms interested in increasing their profits should click here (and ignore the bit about lower CEO compensation).

Hat tip: Professor Bainbridge.

Corporate Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence from Fertility Clinics

Corporate investors are often credited with boosting target firm performance but criticized for prioritizing profits over consumer well-being. This tension is particularly evident in the healthcare sector, where information frictions contribute to underinvestment in quality. This paper finds that corporate ownership can improve healthcare outcomes in a setting where patients have access to service pricing and quality information – the market for In Vitro Fertilization (IVF). After acquisition by a fertility chain, clinic volume increases by 28.2%, and IVF success rates increase by 13.6%. Fertility chains also implement changes that enhance quality, benefit underperforming clinics, and expand the IVF market.

That is from a new paper by Amber La Forgia and Julia Bodner. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Some points about corporate tax

Written from the British context:

Should the system be changed to one where companies are taxed on all the profits they make from their sales in the country?

There are a few downsides to this.

First of all it would be very hard for one country to switch to such a system without getting the rest of the world to do it too. If we did it unilaterally it would open up more differences between national tax regimes and so create, rather than reduce tax avoidance loopholes.

It is also far from clear the UK would gain from such a change. We might gain from some of the big US-based multinationals paying more tax here, but we have plenty of multinationals of our own and they would generally end up paying less here. The biggest losers could well be poorer developing countries, especially those reliant on extractive industries such as mining. If they could only tax companies based on their sales to their residents in that country that would bring in a lot less than taxing them on the share of the economic value of the products generated in that country. The UK itself still generates between 8 and 9 percent of Government revenues from corporation tax, which is pretty respectable internationally, despite being a very open economy exposed to competition.

There is also an economic question as to who ultimately bears the burden of taxes on a company – is it the shareholders, the customers, or the workers, and if the workers, is it the highly-paid top management or the people at the bottom? The answer is not certain, but it does seem likely that a shift to sales-based tax would be at the expense of the customers. In other words, by taxing internet-based suppliers more, we could be more heavily taxing ourselves.

But the strongest argument against is fairness. If a product is invented / developed / mined / refined / built and potentially even marketed and sold all round the world entirely from country X, making use of staff educated in country X, who use country X’s health care system and transport network, often with tax breaks from country X to encourage its growth, and maybe even wage subsidies from country X for its employees, who deserves to be able to tax the company’s profits? Is it country X, or every country that has someone in it who buys a product from the company? Of course if a country wants to tax sales it can, and sales taxes such as VAT are a perfectly reasonable and sensible part of a country’s tax mix; though in the EU, this is governed to a considerable extent by EU rules.

There are many further detailed points at the link. And do note this:

There is a perceived issue with the internet making it easier than ever for companies to ‘sell into’ a country with little or no presence in that country, and therefore offering little or no taxable base for the government of that country to tax the profits of. Sales taxes can be part of the answer to this.

But of course a sales tax does not appear to consumers to be a free lunch, and so it is not as politically popular as a sales-based hike in corporate rates. And so we arrive at the current mess of a situation: “We want tax equity, but you can’t possibly expect us to do that in a way that is transparent!”

Why cut the corporate tax rate under full expensing?

Second, that there is some pure “profit,” some pure “rent,” some “unreproducible input” (i.e. something that did not come from a past unmeasured investment), something like the classic “unimproved land” that can be taxed, without distorting any decision. It goes hand in hand with the complaints of greater monopoly.

But I find it hard to find and name a concrete source of profits that, once named, does not distort the decision to undertake some useful activity to make those profits. Starting, organizing, and improving a business, figuring out the intangible organizational capital that makes it a successful competitor, creating a product and a brand name, are all crucial activities for which no investment tax credit will successfully offset a large profits tax. “Intangible capital” is about all most companies have these days.

That is John Cochrane replying to Stephen Williamson, there is much more at the link. I would add also that Williamson’s model seems to take “r” as constant.

Corporate Taxation and Capital Taxation

In the debate over corporate taxation it’s often assumed that corporate taxes are equivalent to taxes on capital. But corporations are only a minority of firms. Most of the firms in the pass-through sector are small partnerships but by no means are all pass-through firms small. Indeed, corporate profits are less than half of all business profits as shown by the following graph from the Tax Foundation.

What this means is that a cut in the income tax is also a cut in the capital tax. Indeed, a cut in the top marginal income tax rate is a bigger cut in capital taxation than a cut in the top corporate tax rate. (Unfortunately, it now looks like the top marginal rate on income won’t be cut.)

What this means is that a cut in the income tax is also a cut in the capital tax. Indeed, a cut in the top marginal income tax rate is a bigger cut in capital taxation than a cut in the top corporate tax rate. (Unfortunately, it now looks like the top marginal rate on income won’t be cut.)

Since pass through businesses can be large, some people have suggested that these businesses should be taxed like corporations. That would be a mistake. An ideal tax system should be neutral as to organizational form. So, if anything, corporate taxation should be moved more in the direction of pass-through taxation.

Hat tip: Lunch with Steve Pearlstein, Bryan Caplan and Tyler.

Should there be a tax on corporate income at all. For and against.

That is a reader request. I used to think the ideal tax rate on corporations should be zero, but that is no longer my view. For one thing, too many individuals would find ways to self-incorporate, thereby avoiding personal income taxes on labor income. Note that a small corporation controlled by you can return real income to you in a variety of non-taxable or less-taxed ways.

Furthermore, tax-exempt institutions such as non-profits and pension fund would end up owning too many corporations, to the detriment of (non-tax) efficiency. While pension funds eventually must pay out that income in the form of pensions, those often go to high-wealth, low income elderly individuals, and thus would never end up taxed at such a high rate.

I now think that for the United States the tax rate on corporate income should be in the range of 18-25 percent, depending of course on what other decisions we make with our budget and tax systems. It also would work to simply target the OECD average of the corporate rate.

A further question is whether the case for a zero corporate rate would be stronger if we shifted from income to consumption taxation. That depends how easy it might be to partially evade the consumption tax, say by spending money abroad. In general, to the extent evasion is possible that favors lower marginal tax rates but levied on a greater number of distinct points in the system, including in this case on the corporate veil.

I thank Megan McArdle for a useful conversation related to these points.

Intangible investment and monopoly profits

I’ve been reading the forthcoming Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy, by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake, which is one of this year’s most important and stimulating economic reads (I can’t say it is Freakonomics-style fun, but it is well-written relative to the nature of its subject matter.)

The book offers many valuable theoretical points and also observations about data. And note that intangible capital used to be below 30 percent of the S&P 500 in the 70s, now it is about 84 percent. That’s a big increase, and yet the topic just isn’t discussed that much (I cover it a bit in The Complacent Class, as a possible source of increase in business risk-aversion).

Here is one option Haskel and Westlake lay out, though I am not sure to what extent they are endorsing it, as opposed to merely presenting it:

1. More intangible capital means greater spillovers across firms. Consider Apple inventing the iPhone, and many other companies free-riding upon the original R&D. Of course Apple itself was free-riding upon earlier attempts to build smartphones and tablets.

2. In essence, free-riding companies receive more intangible assets, a kind of free lunch on the side of what otherwise would be expenditures on fixed costs. But receiving these intangible benefits itself requires a kind of scale, so they are not available to each and every potential entrant.

3. Corporate profits go up for some of the winners, but monopoly has not risen in the traditional sense. In fact, more companies are competing for the smart phone market.

4. Eventually those profits will fall, as for instance iPhone imitators will force Apple to lower prices for its devices. But that long-run can be quite far away, and as you probably know after ten years iPhone prices have pretty much held firm.

5. Now how big a productivity gain comes from those cross-firm externalities? It might depend on how many other firms are sufficiently well-scaled to receive the intangible external benefits from the first-mover innovators (this part of the argument in particular I am not sure I find in the book).

6. The so-called “superstar” firms are those that scale up to capture intangible externalities from many other sources, not just one or two. That includes Google and Facebook, but most firms don’t have the talent or cash pile to make that leap. Therefore these gains remain concentrated, income inequality goes up, both in general, and across business firms, as indeed we observe in the data. Since entry into “holding a position to capture a broad swathe of intangible externalities” to tough to accomplish, this state of affairs can persist for some while. Yet, still, in no particular market are mark-ups over marginal cost worse, nor are monopoly problems worse from the point of view of consumers. Profits of the superstar firms are much higher. Arguably that is a pretty decent description of the American economy today.

7. You can think of these conditions, collectively, as arranging a big transfer to some leading businesses, yet without distorting too many other margins.

Now, I’ve put that all into my language and framing, rather than theirs. In any case, I suspect that many of the recent puzzles about mark-ups and monopoly power are in some way tied to the nature of intangible capital, and the rising value of intangible capital.

The one-sentence summary of my takeaway might be: Cross-business technology externalities help explain the mark-up, market power, and profitability puzzles.

You should all pre-order and then read this book, due out in late November. I thank PUP for the review copy.

Problems with destination-based corporate taxes and the Ryan blueprint

That is a recent paper by Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Kimberly Clausing. It has content throughout, but this struck me as the most interesting section:

1. A U.S. pharmaceutical with foreign subsidiaries could develop its intellectual property in the United States (claiming deductions for wages, overhead and R&D), and then sell (i.e., export) the foreign rights to its Irish subsidiary (at the highest price possible). The proceeds would not be taxable. Ireland would allow that subsidiary to amortize its purchase price. This creates tax benefits in each jurisdiction by reason of the different regimes. If the Irish subsidiary manufactures drugs, the profits could be distributed up to the U.S. parent tax-free under a territorial system. If the Irish subsidiary is in danger of becoming profitable for Irish tax purposes, the U.S. parent would just sell it more IP.

2. If an Irish parent owns a U.S. subsidiary, the Irish parent can issue debt to fund the purchases of the IP. The U.S. subsidiary then invests the cash to generate more IP (expensing all equipment and deducting all salaries) and sells the IP to its parent.

3. If an Irish parent has purchased the U.S. IP rights, it would not want to license the rights to the U.S. subsidiary (income for Irish parent under Irish tax law and no deduction for U.S. subsidiary). So it just contributes the rights to another U.S. subsidiary. Could the U.S. subsidiary amortize the parent’s basis under the Blueprint? When one U.S. subsidiary licenses to another, no net tax would be paid. Any royalties would be taxable to the licensor but deductible for the payor.

4. How does the Blueprint work for services? If a U.S. hedge fund manager provides services to an offshore hedge fund, is that considered an export that is tax exempt? What if the U.S. manager develops a trading algorithm and sells it (or licenses) it to an offshore hedge fund? Are the proceeds and royalties exempt? If so, then the hedge fund becomes a giant tax shelter to the manager, because he would not pay 25% on this income–he would pay zero, with no further tax. This is much better than the current carried interest provision, which has attracted bipartisan condemnation because it enables individuals with income of many millions to pay a reduced rate. The Blueprint result is much worse.

Should we abolish the corporate income tax and raise taxes on shareholders?

Mike Lee says yes, see also Matt. Maybe, I would like to go this route, but I’m not (yet?) convinced. What if non-profits and foreign companies end up as the shareholders, as indeed the Coase theorem would seem to indicate? Doesn’t that lower tax revenue because they wouldn’t be making capital gains filings? And to some extent, isn’t the U.S. tax system then encouraging inefficient ownership and governance?

There may be an answer to this worry, but I’ve yet to see it.

How might corporate income tax be changed?

This is what is circulating in the House, Trump and the Senate have yet to influence it directly:

KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CURRENT U.S. CORPORATE TAXES AND HOUSE GOP PROPOSAL

Corporate Tax Rate:

Current: 35%

Proposal: 20%Capital Expenses:

Current: Depreciated over time

Proposal: Deducted immediatelyInterest Expenses:

Current: Deductible.

Proposal: Net interest expense not deductibleBasis for Location of Taxation:

Current: Profits

Proposal: SalesTaxation of Foreign Profits:

Current: Pay foreign tax, pay U.S. tax upon repatriation, minus foreign tax credits

Proposal: Generally repatriated without U.S. taxes, after one-time transition taxBorder Adjustments:

Current: None

Proposal: Tax applied to imports, removed from exports

There is more at the WSJ link, a very clear and useful piece by Richard Rubin. Do note that a stronger dollar — which we already see — will undo some of this effort to put American exports on a stronger footing. And deducting capital expenses immediately seems like an attempt to goose up the current economy in an unwise and unsustainable fashion. The lower corporate tax rate is a good idea. What are your opinions on these changes?