Results for “germany recession” 26 found

The strange recession that is Czechia (from my email)

From the very perceptive Kamil Kovar, these are his words I will not double indent:

“Seeing your recent brief post on recession I was wondering whether you are thinking about writing a longer post on the topic of recessions in general? I find the recent macroeconomic developments very intriguing, as they challenge my previous notions of what is a recession and what pushes us into recession, and would be very interested in hearing what you think.

To be more specific, let me use European developments, which I think are even more thought-provoking from this perspective than US developments. Take an extreme example of Czechia, which combines following facts:

- GDP has contracted for two quarters in a row, each time around 0.3% non-annualized. It is still below its pre-pandemic peak.

- Consumption has contracted for 5 quarters in a row, cumulatively 7.6%.

- Fixed investment has decreased in last quarter as well, albeit after strong recovery throughout the previous year and a half.

- The reason why GDP did not drop more is because net exports surged from their extremely low values reached during the pandemic period. In last quarter government consumption also helped a lot.

- Despite all the weakness, labor market is tight, with unemployment rate close to its pre-pandemic historical lows (in case you don’t know, it is ridiculously-sounding low at 2.1%), and employment continuing to grow.

(This as of March; more recent data continued in these trends, albeit GDP overall increased a tad bit. Also, Germany is going through something similar, albeit at much smaller scale).

It feels like this combination just does not fit in together in terms of standard macroeconomics – if you would tell me only about consumption (2) I would say the country has to be in recession, but investment (3) and labor market (5) are clearly saying no recession. If it would be just labor market, then I could accept that it is case of labor hoarding distorting the picture, but investment also remaining robust is just hard to reconcile with recession.

So I was wondering in what way, if any, did the last update your beliefs about “what is a recession and what pushes us into recession” in the light of the puzzling macroeconomic data of last year or so…

P.S.: In case you want to read more on the case of Czechia, or my take on what it all means, I had a blog post few months back:

https://kamilkovar.substack.com/p/it-or-isnt-it-recession-on-regular

My way of reconciling the data with my mental models is that got real shocks pushing us into RBC-style recession, but for whatever reason we did not get the typical demand shocks that lead to a more standard recession.”

TC again: Worth a ponder!

Does Demand for New Currencies Increase in a Recession?

Every time there is a recession we hear more about barter and new currencies, especially so-called “local” currencies. An inceased interest in barter and new currencies suggests a theory of recessions, the lack of liquidity theory:

Bloomberg: “In times of crisis like the one we are jumping into, the main issue is lack of liquidity, even when there is work to be done, people to do it, and demand for it,” says Paolo Dini, an associate professorial research fellow at the London School of Economics and one of the world’s foremost experts on complementary currencies. “It’s often a cash flow problem. Therefore, any device or instrument that saves liquidity helps.”

I wrote about this several years ago but on closer inspection it’s not obvious that interest in barter or new currencies increases much in a recession or that these new currencies are helpful. Here’s my previous post (with a new graph) and no indent.

Nick Rowe explains that the essence of New Keynesian/Monetarist theories of recessions is the excess demand for money (Paul Krugman’s classic babysitting coop story has the same lesson). Here’s Rowe:

The unemployed hairdresser wants her nails done. The unemployed manicurist wants a massage. The unemployed masseuse wants a haircut. If a 3-way barter deal were easy to arrange, they would do it, and would not be unemployed. There is a mutually advantageous exchange that is not happening. Keynesian unemployment assumes a short-run equilibrium with haircuts, massages, and manicures lying on the sidewalk going to waste. Why don’t they pick them up? It’s not that the unemployed don’t know where to buy what they want to buy.

If barter were easy, this couldn’t happen. All three would agree to the mutually-improving 3-way barter deal. Even sticky prices couldn’t stop this happening. If all three women have set their prices 10% too high, their relative prices are still exactly right for the barter deal. Each sells her overpriced services in exchange for the other’s overpriced services….

The unemployed hairdresser is more than willing to give up her labour in exchange for a manicure, at the set prices, but is not willing to give up her money in exchange for a manicure. Same for the other two unemployed women. That’s why they are unemployed. They won’t spend their money.

Keynesian unemployment makes sense in a monetary exchange economy…it makes no sense whatsoever in a barter economy, or where money is inessential.

Rowe’s explanation put me in mind of a test. Barter is a solution to Keynesian unemployment but not to “RBC unemployment” which, since it is based on real factors, would also occur in a barter economy. So does barter increase during recessions?

There was a huge increase in barter and exchange associations during the Great Depression with hundreds of spontaneously formed groups across the country such as California’s Unemployed Exchange Association (U.X.A.). These barter groups covered perhaps as many as a million workers at their peak.

In addition, I include with barter the growth of alternative currencies or local currencies such as Ithaca Hours or LETS systems. The monetization of non-traditional assets can alleviate demand shocks which is one reason why it’s good to have flexibility in the definition of and free entry into the field of money (a theme taken up by Cowen and Kroszner in Explorations in New Monetary Economics and also in the free banking literature.)

During the Great Depression there was a marked increase in alternative currencies or scrip, now called depression scrip. In fact, Irving Fisher wrote a now forgotten book called Stamp Scrip. Consider this passage and note how similar it is to Nick’s explanation:

If proof were needed that overproduction is not the cause of the depression, barter is the proof – or some of the proof. It shows goods not over-produced but dead-locked for want of a circulating transfer-belt called “money.”

Many a dealer sits down in puzzled exasperation, as he sees about him a market wanting his goods, and well stocked with other goods which he wants and with able-bodied and willing workers, but without work and therefore without buying power. Says A, “I could use some of B’s goods; but I have no cash to pay for them until someone with cash walks in here!” Says B, “I could buy some of C’s goods, but I’ve no cash to do it with till someone with cash walks in here.” Says the job hunter, “I’d gladly take my wages in trade if I could work them out with A and B and C who among them sell the entire range of what my family must eat and wear and burn for fuel – but neither A nor B nor C has need of me – much less could the three of them divide me up.” Then D comes on the scene, and says, “I could use that man! – if he’d really take his pay in trade; but he says he can’t play a trombone and that’s all I’ve got for him.”

“Very well,” cries Chic or Marie, “A’s boy is looking for a trombone and that solves the whole problem, and solves it without the use of a dollar.

In the real life of the twentieth century, the handicaps to barter on a large scale are practically insurmountable….

Therefore Chic or somebody organizes an Exchange Association… in the real life of this depression, and culminating apparently in 1933, precisely what I have just described has been taking place.

What about today (2011)? Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t keep statistics on barter (although barterers are supposed to report the value of barter exchanges). Google Trends shows an increase in searches for barter in 2008-2009 but the increase is small. Some reports say that barter is up but these are isolated (see also the 2020 Bloomberg piece), I don’t see the systematic increase we saw during the Great Depression. I find this somewhat surprising as the internet and barter algorithms have made barter easier.

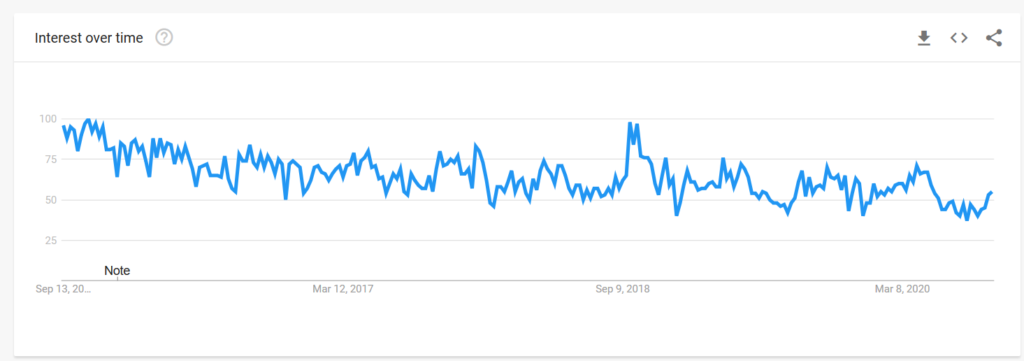

In terms of alternative currencies, the best data that I can find shows that the growth of alternative currencies in the United States is small, sporadic and not obviously increasing with the recession. (Alternative currencies are better known in Germany and Argentina perhaps because of the lingering influence of Heinrich Rittershausen and Silvio Gesell).

Below is a similar graph for 2017-2020. Again not much increase in recent times.

In sum, the increase in barter and scrip during the Great Depression is supportive of the excess demand for cash explanation of that recession, even if these movements didn’t grow large enough, fast enough to solve the Great Depression. Today there seems to be less interest in barter and alternative currencies than expected, or at least than I expected, given an AD shock and the size of this recession. I don’t draw strong conclusions from this but look forward to further research on unemployment, recessions and barter.

Unemployment, Recessions and Barter: A Test

Nick Rowe explains that the essence of New Keynesian/Monetarist theories of recessions is the excess demand for money (Paul Krugman’s classic babysitting coop story has the same lesson). Here’s Rowe:

The unemployed hairdresser wants her nails done. The unemployed manicurist wants a massage. The unemployed masseuse wants a haircut. If a 3-way barter deal were easy to arrange, they would do it, and would not be unemployed. There is a mutually advantageous exchange that is not happening. Keynesian unemployment assumes a short-run equilibrium with haircuts, massages, and manicures lying on the sidewalk going to waste. Why don’t they pick them up? It’s not that the unemployed don’t know where to buy what they want to buy.

If barter were easy, this couldn’t happen. All three would agree to the mutually-improving 3-way barter deal. Even sticky prices couldn’t stop this happening. If all three women have set their prices 10% too high, their relative prices are still exactly right for the barter deal. Each sells her overpriced services in exchange for the other’s overpriced services….

The unemployed hairdresser is more than willing to give up her labour in exchange for a manicure, at the set prices, but is not willing to give up her money in exchange for a manicure. Same for the other two unemployed women. That’s why they are unemployed. They won’t spend their money.

Keynesian unemployment makes sense in a monetary exchange economy…it makes no sense whatsoever in a barter economy, or where money is inessential.

Rowe’s explanation put me in mind of a test. Barter is a solution to Keynesian unemployment but not to “RBC unemployment” which, since it is based on real factors, would also occur in a barter economy. So does barter increase during recessions?

There was a huge increase in barter and exchange associations during the Great Depression with hundreds of spontaneously formed groups across the country such as California’s Unemployed Exchange Association (U.X.A.). These barter groups covered perhaps as many as a million workers at their peak.

In addition, I include with barter the growth of alternative currencies or local currencies such as Ithaca Hours or LETS systems. The monetization of non-traditional assets can alleviate demand shocks which is one reason why it’s good to have flexibility in the definition of and free entry into the field of money (a theme taken up by Cowen and Kroszner in Explorations in New Monetary Economics and also in the free banking literature.)

During the Great Depression there was a marked increase in alternative currencies or scrip, now called depression scrip. In fact, Irving Fisher wrote a now forgotten book called Stamp Scrip. Consider this passage and note how similar it is to Nick’s explanation:

If proof were needed that overproduction is not the cause of the depression, barter is the proof – or some of the proof. It shows goods not over-produced but dead-locked for want of a circulating transfer-belt called “money.”

Many a dealer sits down in puzzled exasperation, as he sees about him a market wanting his goods, and well stocked with other goods which he wants and with able-bodied and willing workers, but without work and therefore without buying power. Says A, “I could use some of B’s goods; but I have no cash to pay for them until someone with cash walks in here!” Says B, “I could buy some of C’s goods, but I’ve no cash to do it with till someone with cash walks in here.” Says the job hunter, “I’d gladly take my wages in trade if I could work them out with A and B and C who among them sell the entire range of what my family must eat and wear and burn for fuel – but neither A nor B nor C has need of me – much less could the three of them divide me up.” Then D comes on the scene, and says, “I could use that man! – if he’d really take his pay in trade; but he says he can’t play a trombone and that’s all I’ve got for him.”

“Very well,” cries Chic or Marie, “A’s boy is looking for a trombone and that solves the whole problem, and solves it without the use of a dollar.

In the real life of the twentieth century, the handicaps to barter on a large scale are practically insurmountable….

Therefore Chic or somebody organizes an Exchange Association… in the real life of this depression, and culminating apparently in 1933, precisely what I have just described has been taking place.

What about today? Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t keep statistics on barter (although barterers are supposed to report the value of barter exchanges). Google Trends shows an increase in searches for barter in 2008-2009 but the increase is small. Some reports say that barter is up but these are isolated, I don’t see the systematic increase we saw during the Great Depression. I find this somewhat surprising as the internet and barter algorithms have made barter easier.

In terms of alternative currencies, the best data that I can find shows that the growth of alternative currencies in the United States is small, sporadic and not obviously increasing with the recession. (Alternative currencies are better known in Germany and Argentina perhaps because of the lingering influence of Heinrich Rittershausen and Silvio Gesell).

In sum, the increase in barter and scrip during the Great Depression is supportive of the excess demand for cash explanation of that recession, even if these movements didn’t grow large enough, fast enough to solve the Great Depression. Today there seems to be less interest in barter and alternative currencies than expected, or at least than I expected, given an AD shock and the size of this recession. I don’t draw strong conclusions from this but look forward to further research on unemployment, recessions and barter.

The fiscal economics of Nazi Germany, part II

I am a big fan of the columns of David Leonhardt but I do not quite agree with his latest interpretation of fiscal policy in Nazi Germany. David writes:

More than any other country, Germany – Nazi Germany – then set out

on a serious stimulus program. The government built up the military,

expanded the autobahn, put up stadiums for the 1936 Berlin Olympics and

built monuments to the Nazi Party across Munich and Berlin.

The

economic benefits of this vast works program never flowed to most

workers, because fascism doesn’t look kindly on collective bargaining.

But Germany did escape the Great Depression

faster than other countries. Corporate profits boomed, and unemployment

sank (and not because of slave labor, which didn’t become widespread

until later). Harold James, an economic historian, says that the young liberal economists studying under John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s began to debate whether Hitler had solved unemployment.

If I am reading this correctly, the implication is that fiscal policy worked but the German economy had a bad and worsening distribution of wealth. I would sooner say that fiscal policy did not work and the German economy had a bad and worsening distribution of wealth.

In 1933 military spending was 2 percent of German national income; by 1940 it was 44 percent, with a steady rise along the way. The contemporaneous boost in measured gdp was almost completely an illusion in terms of human welfare (breaking the Versailles commitments did help Germany) and that includes corporations and their owners. It is not that labor could not grab its fair share of the pie but rather that fiscal policy did not increase the size of the true (non-militaristic) pie. If you want to see gnp figures for that period turn to p.25 of this paper by Albrecht Ritschl (and the discussions starting on p.4 on how to properly measure gnp during this time). Ritschl offers a pessimistic account of the net contribution of fiscal policy and the abstract of his related paper sums it up well:

This

paper examines the effects of deficits spending and work-creation on

the Nazi recovery. Although deficits were substantial and full

employment was reached within four years, archival data on public

deficits suggest that their fiscal impulse was too small to account for

the speed of recovery. VAR forecasts of output using fiscal and

monetary policy instruments also suggest only a minor role for active

policy during the recovery. Nazi policies deliberately crowded out

private demand to ensure high rates of rearmament. Military spending

dominated civilian work-creation already in 1934. Investment in

autobahn construction was minimal during the recovery and gained

momentum only in 1936 when full employment was approaching. Continued

fiscal and monetary expansion after that date may have prevented the

economy from sliding back into recession. We find some effects of the

Four Years Plan of late 1936, which boosted government spending further

and tightened public control over the economy.

McDonough indicates that economic growth in the Nazi 1930s was due primarily to arms spending, or again it was not real economic growth at all. This piece has much useful detail on private German consumption during the era and again the conclusions are pessimistic. Of course employment rose dramatically but it does not seem that real (non-militaristic) consumption and output did very well. There was militaristic make-work, based on transfers from one group to another, but with few accompanying economic benefits.

On the corporate side, there is this:

It is interesting to note that German productivity only grew 1.3% per

year from 1929 to 1938, roughly half the growth rate of Britain in the

same period.

Productivity statistics can mean a number of things but again this does not make the German corporate sector sound totally healthy or sustainable.

It could be argued that the Nazi policies did not work because they

stifled private consumption and in that regard they were not Keynesian in the modern

sense. Maybe so, but we're still back at the Nazi policies not having worked. I don't consider this research, in sum, "knock down" evidence, but still my view of Nazi fiscal policy is more negative than in Leonhardt's.

Here is my previous post on the fiscal economics of Nazi Germany.

European inflation was more painful for the elderly

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

As recent research indicates, the recent inflation has been very costly. The 2021-2022 inflation cost more than 3% of national income in France, Germany and Spain, and about 8% of national income in Italy, higher costs than what a typical recession would bring.

It is striking how much those costs fall on the elderly, which is one reason that lowering inflation rates has been such a priority. The elderly usually have the most accumulated savings, and less time to make up for inflationary losses by subsequent compounding. Older people are also more likely to own homes, so face higher home heating bills when energy prices rise. Overall, in the last several years, a low-income retired household in Italy might have taken income cuts of up to 20%, while a middle-aged household in the euro area might have seen a typical income cut of 5%.

…Not everyone lost from the inflation. Young households in Spain, for instance, gained more than 5% in income. The simplest way a household might gain from inflation is that its debt liabilities decline in real, inflation-adjusted value. On average, the young are more likely to be in debt than the elderly, and own fewer assets. Inflation also tends to lower the value of tenured jobs, such as in academia, and younger people are less likely to hold such posts. The young also tend to have more time in their lives to adjust to negative economic shocks, by for instance geographic or career migration.

Overall, an estimated 30% of the households in the euro area gained from the inflationary shock. Almost half of 25- to 44-year-olds benefited.

On net, the inflation remains a clear negative. But how many other eurozone policies manage to favor the young?

Here is the underlying research by Filippo Pallotti, Gonzalo Paz-Pardo, Jiri Slacalek, Oreste Tristani, and Giovanni L. Violante.

Disputes over China and structural imbalances

There has been some pushback on my recent China consumption post, so let me review my initial points:

There exists a view, found most commonly in Michael Pettit (and also Matthew Klein), that suggests economies can have structural shortfalls of consumption in the long run and outside of liquidity traps.

My argument was that this view makes no sense, it is some mix of wrong and “not even wrong,” and it is not supported by a coherent model. If need be, relative prices will adjust to restore an equilibrium. If relative prices are prevented from adjusting, the actual problem is not best understood as a shortfall of consumption, and will not be fixed by a mere expansion of consumption.

Note that people who promote this view love the word “absorb,” and generally they are reluctant to talk much about relative price adjustments, or even why those price adjustments might not take place.

You will note Pettis claims Germany suffers from a similar problem, America too though of course the inverse version of it. So whatever observations you might make about China, the question remains whether this model makes sense more generally. (And Australia, which ran durable trade deficits from the 1970s to 2017, while putting in a strong performance, is a less popular topic.)

Pettis even has claimed that “US business investment is constrained by weak demand rather than costly capital”, and that is from April 4, 2023 (!).

It would take me a different blog post to explain how someone might arrive at such a point, with historic stops at Hobson, Foster, and Catchings along the way, but for now just realize we’re dealing with a very weird (and incorrect) theory here. I will note in passing that the afore-cited Pettis thread has other major problems, not to mention a vagueness about monetary policy responses, and that rather simply the main argument for current industrial policy is straightforward externalities, not convoluted claims about how foreign and domestic investment interact.

Pettis also implicates labor exploitation as a (the?) major factor behind trade surpluses, and furthermore he considers this to be a form of “protectionism.” Now you can play around with scholar.google.com, or ChatGPT, all you want, and you just won’t find this to be the dominant theory of trade surpluses or even close to that. As a claim, it is far stronger than what a complex literature will support, noting there is a general agreement that lower real wages (ceteris paribus) are one factor — among many — that can help exports. This point isn’t wrong as a matter of theory, it is simply a considerable overreach on empirical grounds. Of course, if Pettis has a piece showing statistically that a) there is a meaningful definition of labor exploitation here, and b) it is a much larger determinant of trade surpluses than the rest of the profession seems to think…I would gladly read and review it. Be very suspicious if you do not see such a link appear!

Another claim from Pettis that would not generate widespread agreement is: “…in an efficient, well-managed, and open trading system, large, persistent trade imbalances are rare and occur in only a very limited number of circumstances.” (see the above link) That is harder to test because arguably the initial conditions never are satisfied, but it does not represent the general point of view, which among other things, considers persistent differences in time preferences and productivities across nations.

Now, it does not save all of this mess to make a series of good, commonsense observations about China, as Patrick Chovanec has done (Say’s Law does hold in the medium-term, however). And as Brad Setser has done.

In fact, those threads (and their citation) make me all the more worried. There is not a general realization that the underlying theory does not make sense, and that the main claim about the determinants of trade surpluses is wrong, and that it requires a funny and under-argued tracing of virtually all trade imbalances to pathology. And to be clear, this is a theory that only a small minority of economists is putting forward. I am not the dissident here, rather I am the one delivering the bad news.

So the theory is wrong, and don’t let commonsense, correct observations about China throw you off the scent here.

Should we now conclude that the euro is just fine?

No, and that is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column:

The core difficulties of the euro arise when two circumstances coincide: There are deflationary pressures, and economic conditions vary greatly among the nations of the euro zone. The good news is that neither of these circumstances currently prevails. That is also the bad news.

Inflation rates have been high, especially in the euro zone, and are expected to be higher than 9% for December 2022. Inflation brings problems of its own (more about that later), but in the short run it does not lead to huge unemployment and loan defaults. If anything, it helps out some debtors.

During the 2011 crisis, there was massive deflationary pressure on the Greek banking system, endangering its solvency. The Greek government’s deposit guarantees were not entirely credible either, so many people withdrew their deposits, increasing pressure on both the government and the banks. Whatever problems euro zone nations may have today, they are not those.

A second issue in 2011 was that some nations were doing much better than others. Germany had a relatively strong economy, while Greece and Italy’s were relatively weak. Greece, Italy and some of the other “periphery” nations would have preferred a weaker euro, to boost their exports, but the strength of Germany and some of the other more prosperous euro-zone nations limited euro deprecation.

Today, problems in the euro zone are more evenly distributed. Current data indicate a shallow rather than deep recession, but countries such as Germany still face real challenges. The euro, in turn, has been relatively weak, which has limited some of the downside risk faced by the euro-zone economies…

Unfortunately, those mechanisms postpone but do not eliminate the core problems with the euro zone. First, if the zone works better in inflationary times, politicians committed to it will become more attached to higher rates of inflation. That will make it harder for the European Central Bank to achieve its goal of price stability.

And:

The second problem is this: High inflation eventually brings a process of disinflation, and during those disinflations real interest rates are often high. The ECB hikes nominal interest rates, and as inflation diminishes those rates rise in real, inflation-adjusted terms. In other words, some deflationary pressures are brought to bear on the system.

Those deflationary pressures are exactly what the euro zone does not handle well. Italy in particular faces ongoing fiscal problems, and if its government had to borrow at much higher real rates of interest, its current fiscal path may not prove sustainable. It might be forced to cut government spending and/or raise taxes, which would lead to the kind of downward spiral that characterized the earlier euro-zone crisis.

Diverging economic fortunes for euro zone nations may reemerge as well…

So I think people are being a bit too optimistic about Croatia joining the eurozone.

Remember when people used to savage real business cycle theory?

In Germany, where one in four jobs depends on exports, the crisis gumming up the world’s supply chains is weighing heavily on the economy, which is Europe’s largest and a linchpin to global commerce.

Recent surveys and data point to a sharp slowdown of the German manufacturing powerhouse, and economists have begun to predict a “bottleneck recession.”

Almost everything that German factories need to operate is in short supply, not just computer chips but also plywood, copper, aluminum, plastics and raw materials like cobalt, lithium, nickel and graphite, which are crucial ingredients of electric car batteries.

And this:

The widespread assumption that suppliers close to home are more reliable has not always proved true. During the turmoil caused by the pandemic, some German companies had more trouble getting supplies from France or Italy, because of strict lockdowns, than they did from Asia.

Here is the full NYT piece by Jack Ewing, recommended.

Friday assorted links

1. Balaji on heterogeneities and data integration.

2. Citizen’s handbook for nuclear attack and natural disasters. Do we need a new version of this?

3. The Amazon: “We show that, starting at around 10,850 cal. yr BP, inhabitants of this region began to create a landscape that ultimately comprised approximately 4,700 artificial forest islands within a treeless, seasonally flooded savannah.”

4. How much distance do you need when exercising? And against crowded spaces.

5. Dan Wang letter from Beijing in New York magazine.

6. Trump pushing to reopen by May 1.

7. Lots of new testing results from Germany, consider these as hypotheses but still a form of evidence.

8. Good and subtle piece on Tiger King (NYT). And betting markets in everything.

9. The Vietnamese response seems pretty good so far.

10. Joe Stiglitz discusses his love of fiction (NYT)

12. Ronald Inglehart on the shift to tribalism.

13. Explaining the Fed lending programs.

14. MIT Press preprint of new Joshua Gans book on Covid-19, open for public comment.

Is Portugal an anti-austerity story?

A recent NYT story by Liz Alderman says yes, but I find the argument hard to swallow. Here’s from the OECD:

The cyclically adjusted deficit has decreased considerably, moving from 8.7% of potential GDP to 1.9% in 2013 and to 0.9% in 2014. This is better (lower) than the OECD average in 2014 (3.1%), reflecting some improvement in the underlying fiscal position of Portugal.

Or see p.20 here (pdf), which shows a rapidly diminishing Portuguese cyclically adjusted deficit since 2010. Now I am myself skeptical of cyclically adjusted deficit measures, because they beg the question as to which changes are cyclical vs. structural. You might instead try the EC:

…the lower-than-expected headline deficit in 2016 was mainly due to containment of current expenditure (0.8 % of GDP), particularly for intermediate consumption, and underexecution of capital expenditure (0.4% of GDP) which more than compensated a revenue shortfall of 1.0% of GDP (0.3% of GDP in tax revenue and 0.7% of GDP in non-tax revenue)

Does that sound like spending your way out of a recession? Too right wing a source for you? Catarina Principle in Jacobin wrote:

…while Portugal is known for having a left-wing government, it is not meaningfully an “anti-austerity” administration. A rhetoric of limiting poverty has come to replace any call to resist the austerity policies being imposed at the European level. Portugal is thus less a test case for a new left politics than a demonstration of the limits of government action in breaking through the austerity consensus.

Or consider the NYT article itself:

The government raised public sector salaries, the minimum wage and pensions and even restored the amount of vacation days to prebailout levels over objections from creditors like Germany and the International Monetary Fund. Incentives to stimulate business included development subsidies, tax credits and funding for small and midsize companies. Mr. Costa made up for the givebacks with cuts in infrastructure and other spending, whittling the annual budget deficit to less than 1 percent of its gross domestic product, compared with 4.4 percent when he took office. The government is on track to achieve a surplus by 2020, a year ahead of schedule, ending a quarter-century of deficits.

This passage also did not completely sway me:

“The actual stimulus spending was very small,” said João Borges de Assunção, a professor at the Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics. “But the country’s mind-set became completely different, and from an economic perspective, that’s more impactful than the actual change in policy.”

Does that merit the headline “Portugal Dared to Cast Aside Austerity”? Or the tweets I have been seeing in my feed, none of which by the way are calling for better numbers in this article?

I would say that further argumentation needs to be made. Do note that much of the article is very good, claiming that positive real shocks help bring recessions to an end. For instance, Portuguese exports and tourism have boomed, as noted, and they use drones to spray their crops, boosting yields. That said, it is not just the headline that is at fault, as the article a few times picks up on the anti-austerity framing.

I’m going to call “mood affiliation” on this one, at least as much from the headline and commentary surrounding the article as the author herself.

Was there a Housing Price Bubble? Revisited

In 2005, I thought housing prices were rising above the fundamentals and I said so. In 2008, as the fall in housing prices was well under way, I wrote a blog post and later a NYTimes op-ed saying that the housing price bubble was not nearly as big as people thought. I wrote:

I think that housing prices went beyond the fundamentals sometime around 2004…but 2004 levels are still well above long run trend.

…Prices will probably drop some more but personally I don’t expect to ever again see index values around 110. Do you? If we don’t see the massive drop back to “normal” levels then the run up in prices should be described as a shift to a new equilibrium…[with some overshooting, rather than as a bubble.]

To put it mildly, not everyone agreed with my argument. I certainly got the timing wrong–I didn’t think the recession would be as long or as deep as it was. Nevertheless, some people are coming round to my point of view. Karl Smith, for example, has a new post Was There Ever a Bubble in Housing Prices? which concludes more or less, as I did nearly ten years earlier, that the answer is no. What happened was greater liquidity which made housing prices gyrate more like stock prices but “the fundamental driver isn’t irrational bubble behavior. It is competition over a scarce resource.”

Let’s go back to the Shiller graph (now updated to 2018 with some slight corrections since 2017 post). Over the entire 20th century real home prices averaged an index value just under 100 (and over the the entire second half of the 20th century were only slightly higher at 112). Over the entire 20th century, housing prices never once rose above 131, the 1989 peak. But beginning around 2000 house prices seemed to reach for an entirely new equilibrium. In fact, even given the financial crisis, prices since 2000 fell below the 20th century peak for only a few months in late 2011. Real prices today are now back to 2004 levels and rising. As I predicted in 2008, prices never returned to their long-run 20th century levels.

Now one might argue that there is still a bubble or perhaps another bubble in housing prices. But the United States does not look anomalous compared to other countries. In fact, in many other countries prices have risen more than in the United States. Here is the Economist’s Global Price Index of real house prices for a variety of countries. (Do note that some countries not shown, such as Germany, haven’t seen big increases in prices.) Are all these countries experiencing bubbles? Or has the equilibrium changed?

Now one might argue that there is still a bubble or perhaps another bubble in housing prices. But the United States does not look anomalous compared to other countries. In fact, in many other countries prices have risen more than in the United States. Here is the Economist’s Global Price Index of real house prices for a variety of countries. (Do note that some countries not shown, such as Germany, haven’t seen big increases in prices.) Are all these countries experiencing bubbles? Or has the equilibrium changed?

Understanding why the equilibrium has changed is a fundamental issue that I don’t think we yet have a good handle on. My view, is that it’s a combination of expected long-run lower interest rates, greater liquidity, and supply constraints on land. Lower interest rates, for example, mean that durable assets increase sharply in price, all the more so if the rates are expected to stay low. Combine this with greater liquidity (see Smith’s post) and supply restrictions and you can explain most of what is going on in the United States. What I don’t know is if the same explanations work worldwide and can the same factors also be used to explain why land prices haven’t risen in Germany, Japan or Switzerland?

Hat tip: Nathaniel Bechhofer.

Keynes is slowly losing (winning?)

Paul Krugman has an interesting blog post arguing that Keynes is slowly winning. But, I must admit, I find it dismaying how little of the contrary evidence is considered. Let’s say you set out to write a blog post about Keynes losing, what might you cite?:

1. Keynesians predicted disaster following the American fiscal sequester, and the pace of the recovery accelerated.

2. Even Obama and the Democrats are writing down, and seeing through, budgets with declining levels of discretionary spending.

3. The UK saw a rapid recovery, and the BOE kept nominal gdp growing at a good pace, even in the presence of a so-called “liquidity trap.” This is not mainly due to the UK having “stopped tightening,” nor did the Continental economies which let up on austerity see similar recoveries. Nor had the Keynesians predicted that letting up on tightening would bring such a strong recovery, Summers for instance had predicted exactly the opposite.

4. Rate of change recoveries in the Baltics — which really did try a kind of radical austerity — have been stronger and more rapid than Keynesians were predicting, even if absolute levels remain less than ideal.

5. France doesn’t seem to have much interest in trying additional government spending, even though their economy is flailing and no other attempted remedies have been successful.

6. Ireland finally is seeing a rapid recovery, albeit one with highly uneven distributional consequences and possibly another real estate bubble. The “get the pain over with” approach is looking better right now than it did say two years ago.

7. It is the ECB which seems to hold all of the levers in the eurozone, and the Japanese central bank which is making the (possibly failed) splash in Abenomics. That may be anti-anti-Keynesian, but it’s not exactly Keynesian either.

8 The Chinese have moved to discount rate cuts, and they seem to realize that more fiscal spending will only postpone their day of reckoning in terms of excess capacity. That’s not an “anti-Keynesian” attitude, given the current features of their economy, but it’s not exactly screaming the relevance of Keynes’s GT either.

9. It looks like Germany actually will support some additional infrastructure spending. You could call that a Keynesian victory, but more likely it also will be used to shut down further debate. Here is one estimate of what will be done. It’s not that much.

10. Japan is in a (supposed) liquidity trap, but negative real shocks have not in fact helped their economy, contra to the predictions of that model (start with here and here). Nor does anyone think that the bad weather in the first quarter of U.S. 2014 was good for us, although a basic liquidity trap model implies it will boost inflation (beneficially) because the supply restrictions lead to price hikes which tax currency holdings and thus boost AD. Come on, people, that is weak.

11. A lot of the cited predictions of the Keynesian or liquidity trap model are in fact simple predictions of efficient markets theory (such as on interest rates), predictions of market monetarism or credit-based macro theories (low inflation), or regularities that have held for decades (budget deficits not raising real interest rates). It’s just not that convincing to keep on claiming these predictions as victories for Keynesianism and in fact I (among many others) predicted them all too. I never thought I was much of a sage for getting those variables right.

12. Whether we like it or not, large chunks of Asia still seem to regard Keynesian economics with contempt. They prefer to stress supply-side factors.

13. At the Nobel level, Mortensen, Pissarides, and Fama do not exactly count as Keynesian material, admittedly Shiller is on the other end of the scale, though even there I am not aware he has a strong record of speaking out on behalf of activist fiscal policy.

14. It is now widely acknowledged that there has been a productivity problem in recent times (or maybe longer), and thus those measurements of “the output gap” are looking smaller all the time. Again (a common pattern in these points), nothing there implies “Keynes is wrong,” but it does make Keynes less relevant.

15. Where Keynesian views have looked very good is that government spending cuts do — these days — bring steeper and rougher gdp tumbles than was the case in the 1990s. That is very important, but a) it is increasingly obvious that there is catch-up for countries with OK institutions, and b) correctly or not, the world really hasn’t been convinced there is major upside to expanding fiscal policy.

The point is not that these citations give you a fully balanced view — they don’t! And it would be wrong to conclude that Keynes was anything other than a great, brilliant economist. Rather these citations, plus many of Krugman’s points, give you some beginnings for this issue. It’s not nearly “Keynes’s time” as much as many people are telling us, after all his biggest book is from 1936 and that is a long time ago. Keynes is both winning and losing at the same time, like many other people too, fancy that.

Another way of thinking about the European economic collapse

Let’s start with a few claims that (most) people agree with:

2. The U.S. has higher income inequality than most of Europe and our high earners have done quite well for some time.

3. Many events happen in the U.S. first.

4. The U.S. is more flexible than most European economies, though not obviously more flexible than say Germany or Sweden.

OK, let’s tie those pieces together, but please keep in mind that I consider the following to be speculative.

IT and China, taken together, seem to imply a big whack to median income. This whack should be higher for the less flexible polities, and furthermore the wealthy and the well-educated in the U.S. get back a big chunk of that money through tech innovation and IP rights. Plus we’ve had some good luck with fossil fuels and even the composition of our agriculture. If you had a country without those high earners in the tech sector, and an inflexible labor market, those economies will have to contract and I don’t just mean in a short-term cycle. Equilibrium implies negative growth for those economies, at least for a while.

By how much? If the relatively flexible U.S. lost 8% of median income, perhaps Italy and Spain and Greece have to lose 15%, but with no offsetting major gains on the upper end of the income distribution. (How flexible is Ireland or for that matter France is an interesting question and so far the answer is not obvious.)

In sum, the less flexible European economies will lose at least 15% of their gdps, due to trade and technology.

There is then the question of what the path downwards will look like and feel like. Being in the eurozone makes adjustment much harder, and brings the doom more quickly, for reasons which are by now well-discussed.

The initial path looks like this. The real sectors of those economies start to appear weaker, and this sets off some deposit flight and also a credit contraction. AD and AS fall together and set off some further negative interactions. In the case of Greece the expectation of the country being “a European economy” gets replaced with the expectation of the country being “a Balkan economy,” to the detriment of investment of course. Along the way, the true nature of the EU political equilibrium is revealed, expectations of EU cooperation decline, and that sets off further AD and AS downward spirals.

Trying “austerity” will hasten the fall, but at the same time it is hard to see how an economy contracting by 15% could in the longer run keep its previous level of government spending, or for that matter find a “good” time to do fiscal consolidation. It will appear that “austerity” is more causally important than it really is.

All sorts of particular stories will get told along the way, including the austerity story. Those stories may look true, but ultimately they are more about timing and trajectory than about fundamental causes. What I call “time compression” will very often appear to be causality.

A lot of the problems caused by fiscal consolidation are in fact “sectoral shift” problems. For instance cuts in government spending lay off workers and the Mediterranean private sector — in the midst of a significant contraction and somewhat inflexible to begin with — is unlikely to rehire those workers. The fiscal policy advocates actually have an argument against their “let monetary policy do all the work” critics, although their obsession with AD prevents them from emphasizing the sectoral shift aspects of the fiscal story, which are in fact the paramount aspects.

How much has the Greek economy contracted already? (Hard to say with black markets and bad numbers but I think at least 20%). It is predicted that the Cyprus economy will collapse by 20% over the next three years. Think of their banking sector as unsustainable in the first place, but its decline being hastened rather suddenly by the curious structure of the euro and bank runs (again, time compression). It is not crazy to expect a ten percent permanent contraction for Italy and a very slow recovery for Spain after what is already a major contraction.

By the way, UK employment is now at an all-time high, as jobs have been reshuffled to lower-value service sector activities, and out of oil and finance. Does that fit the Keynesian story? Sorry people, but I have to say “no way.” Maybe the UK economy — which is flexible but not well-geared to export and to compete internationally — is on a path to lose five or ten percent of its gdp, with or without “austerity.”

Empirically, how would one distinguish this story from a more traditional Keynesian account?

1. Both imply that “austerity” appears causally correlated with bad outcomes. (By the way, ngdp targeting is still the way to go, although the lack of such a policy is a secondary or residual problem rather than the primary problem.)

2. Given the massively high unemployment we have seen, the Keynesian account would lead us to expect corresponding rates of price deflation comparable to those of the Great Depression, such as negative ten percent. We’re seeing rates of inflation between zero and two percent, with prices often continuing to move up. Inertia in sticky wages won’t get prices moving up like that, not if AD is supposedly collapsing to an extreme degree and as a driving force. This is pretty close to a “one fact” refutation of the simple Keynesian account. Study economic history all you want, 0-2% inflation may be suboptimal but the associated AD implications simply aren’t that bad, nor will adjusting for a few VAT hikes make it so. What we get is a series of blog posts measuring AD collapse by invoking surrealistic standards, and obscure concepts from modal logic, and failing to notice that price level behavior simply does not fit the story.

3. The Keynesian account implies a fairly quick bounce back for the plagued countries which (eventually) reject “austerity” and goose up AD. The theory here implies a quick bounce back for flexible economies, economies with IP and resources, but no rapid bounce back for the euro periphery, no matter what their policies, at least short of an extremely radical and probably impossible set of structural reforms, such as making Italy into Sweden. In any case, this test has not yet been run as those countries are still on the downswing.

In this account, AD economics, including its Keynesian and neo-monetarist forms, is correct, but it is also far from the entire story.

Stories to watch for in 2013

Here is a list from The Guardian. Here is an FT list. My list looks more like this:

1. Economic turnarounds in the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and possibly Pakistan and Myanmar.

2. Pressures for secession in Catalonia, and a potential crisis of the Spanish state.

3. East Asian belligerence, with more hawkish leaders in the three major countries.

4. There is actually a non-trivial chance we totally blow it on the debt ceiling.

5. The continuing rise of machine intelligence and the general recognition of such as the next major technological breakthrough.

6. Significant positive reforms in Mexico on education, foreign investment, and other matters too.

7. Political collapse in South Africa.

8. Continuation of America’s “Medicaid Wars,” over state-level coverage, combined with the actual implementation of much more of ACA. Continuing attempts in Rwanda, Mexico, and China to significantly extend health care coverage to much poorer populations.

9. The return of dysfunctional Italian politics, combined with the arrival of recession in most of the eurozone economies, including France and Germany.

10. The ongoing barbarization of North Africa, including Mali, Syria, and possibly Egypt. And whether any of these trends will spread to the Gulf states.

11. Whether China manages a speedy recovery and turnaround.

12. Watching India try to overcome its power supply problems, its educational bottlenecks, and its low agricultural productivity.

13. Seeing whether Ghana makes it to “middle income” status and how well broader parts of Africa move beyond resource-based growth.

14. Whether U.S. and also European political institutions can handle the intensely distributional nature of current fiscal questions.

Those are some of the main stories I will have my eye on, but of course I expect to be surprised. I suppose Israel and Iran should be on that list somehow, North Korea too, but I don’t find that thinking and reading about it yields much in the way of return, compared to a simple “wait and see.”

Addendum: Here is Matt’s list.

What views can you hold about Spain?

Choose A or B:

A: Spain is in a recession, which will end. For instance, this story reports: “The OECD on Tuesday predicted more pain for Spain over the next two years when the economy will remain mired in recession with a quarter of the population out of work.”

B: Spain is in a self-cannibalizing downward spiral, as Greece was and is. It will not end until there is, at the bottom, an absolute and total crash.

I choose B, noting that I wrote most of this post a few days ago and already A does not appear to be a serious answer. You add up the required deleveraging, the provincial debts, the shaky state of the banks, the shaky accounting at the banks, the productivity problems, the European-wide political uncertainty, self-defeating fiscal adjustments, the broken real estate lending technology, once-again spiraling yields, broader deflationary pressures, unsatisfactory ngdp performance, the drying up of credit for small and mid-size businesses, disappearance of quality collateral, and the de-europeanisation of the capital markets, and you have B. Oops, I forget to mention the massive proliferation of have-to-pay-them-back-first governmental senior debt claims; why wait in that line?

The fact that you are not used to seeing the credit institutions of an advanced economy unravel before your eyes — “going entropic” — should not blind you to this reality. Nothing new bad has to happen for Spain simply to go “pop,” rather the ticking of the clock will suffice.

Note that a sufficiently large bailout plan, starting with debt forgiveness and reflation, could convert B to A, but right now we are in B.

If you chose A, you think life will be (relatively) easy. I have spoken with numerous intelligent Europeans who believe in A, but because — in my view — they cannot grasp the terribleness of the alternatives, or the magnitude of the error of their previous attachment to the euro, not because they have strong macroeconomic arguments for pending recovery and capital market survival.

If you chose B, there are three more options:

B1: It is a political economy problem. If the Spanish could simply institute the right policies, whatever that might mean, they could convert the destructive spiral into a mere recession.

B2: It is fundamentally a problem of aggregate demand and credit contraction. Without a European-level major bailout and stimulus, Spain will go splat. Yet sufficient stimulus could bring Spain back to its PPF frontier relatively easily.

B3: There is a major problem of aggregate demand and credit contraction, and a political economy problem, and this is paired with multiple equilibria. Investors are judging whether Spain is still a major European economic force, as they had thought for a while, but perhaps had not thought back in 1963. The equilibrium which obtains will depend upon the Spanish response to the crisis, but the best bet is to expect Spain to revert to something, in economic terms, resembling 1999 + Facebook. The institutional quality and level of trust in Spain will receive a semi-permanent downgrade, most of all in the eyes of Spaniards, and it will look very much like an output gap but will not be remediable through traditional macro remedies.

The real euro pessimists are the multiple equilibria people.

Germany and Austria also have multiple equilibria, but those equilibria are not so far apart. For Greece the multiple equilibria are extreme — “Balkans nation,” or “European nation”? Or should I say were extreme?; probably we are down to one of those options at this point.

For Spain, if a truly major bailout does not arrive, the roller coaster ride down will be extreme and terrifying. But still, we must put this in perspective. I was in Spain in 1999 and it was very nice, the large fiction sections of the bookstores most of all, the Basque restaurants too.

I am arriving in Madrid as you read this, perhaps I will have more to say.