Results for “givedirectly” 13 found

GiveDirectly to Administer Cash Grants Pilot in Chicago

Long time readers will know that both Tyler and I have been promoting GiveDirectly since its creation in 2011. GiveDirectly was started by four economists and it gives money directly to the very poor in Kenya and Uganda. Unusually for any charity, GiveDirectly has published substantial, high quality, pre-registered RCTs on its work and is a top-rated charity by GiveWell. GiveDirectly, the charity, continues to do great work helping the world’s poorest people but they are now also using their experience to help design and administer programs in the United States.

A nonprofit that originally focused on giving cash to impoverished people in Africa will soon be delivering money to poor residents of Chicago, in one of the largest tests of a guaranteed basic income program in the US.

GiveDirectly is administering a program that will give $500 a month to each of 5,000 households in Chicago as soon as the end of June. The city is using $31.5 million from the federal government’s American Rescue Plan Act for the year-long pilot, and hoping the payments will help it recover faster from the pandemic.

I look forward to seeing the results.

GiveDirectly

Consider GiveDirectly this holiday season for your charitable giving. As you may recall, GiveDirectly was started by four economists and it gives money directly to the very poor in Kenya and Uganda. GiveDirectly is a top-rated charity by GiveWell. The founders are committed to providing independent, randomized controlled trials of its process. One RCT has already been conducted with positive results and 3 others are under way. GiveDirectly publicizes the trials of its process before the results are produced. Impressive–the drug companies had to be forced to do this. Check out their website, they even provides real-time performance data. Here’s a bit more on their process.

The story of GiveDirectly

Paul Niehaus, Michael Faye, Rohit Wanchoo, and Jeremy Shapiro came up with a radically simple plan shaped by their own academic research. They would give poor families in rural Kenya $1,000 over the course of 10 months, and let them do whatever they wanted with the money. They hoped the recipients would spend it on nutrition, health care, and education. But, theoretically, they could use it to purchase alcohol or drugs. The families would decide on their own.

…Three years later, the four economists expanded their private effort into GiveDirectly, a charity that accepts online donations from the public, as well. Ninety-two cents of every dollar donated to GiveDirectly is transferred to poor households through M-PESA, a cell phone banking service with 11,000 agents working in Kenya. GiveDirectly chooses recipients by targeting homes made of mud or thatch, as opposed to more durable materials, such as cement or iron. The typical family participating in the program lives on just 65 nominal cents-per-person-per-day. Four in ten have had a child go at least a full day without food in the last month.

Initial reports from the field are positive. According to Niehaus, GiveDirectly recipients are spending their payments mostly on food and home improvements that can vastly improve quality of life, such as installing a weatherproof tin roof. Some families have invested in profit-bearing businesses, such as chicken-rearing, agriculture, or the vending of clothes, shoes, or charcoal.

More information on GiveDirectly’s impact will be available next year, when an NIH-funded evaluation of the organization’s work is complete. Yet already, GiveDirectly is receiving rave reviews.

Here is a good deal more. Here is one of my earlier posts on zero overhead giving. Here is Alex’s earlier post. Just last week I met up with one of the recipients of one of my 2007 donations and I am pleased to report he is doing extremely well as an actor and filmmaker.

Here is the site for GiveDirectly. Here is one very positive review of the site, from GiveWell.

Tyler and Alex on Gift Giving

December? It must be time for the holiday favorite that everyone loves, the sweet and wise An Economist’s Christmas!

Effective altruism has taken some hits this year but the core insights remain underrated. We still like the excellent GiveDirectly and also GiveWell’s Top Charity Fund.

Happy holidays everyone!

Sunday assorted links

1. Polysee: Irish YouTube videos about YIMBY, aesthetics, and economics.

2. Germany political map of the day.

3. Thwarted Wisconsin DEI markets in everything.

4. The EU AI regulatory statement (on first glance not as bad as many had expected?).

5. The NBA Play-In was in fact a big success. Is the implication that other sports do not experiment enough with producing more fame/suspense at various margins? Basketball games are simply a much better product when the players are trying their best.

6. Your grandfather’s ACLU is back…for one tweet at least.

7. New GiveDirectly results on lump sum transfers, from Kenya.

8. Ideas matter.

9. The Chinese are using water cannons at sea, against the Philippines.

The Economics of Gift Giving

Tyler and I debate the economics of gift giving.

As usual, we recommend Givewell as the best source for making your altruism effective! GiveDirectly continues to be one of Givewell’s highest ranked charities and they are also doing good economics research.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Dylan Matthews on a Give Directly UBI experiment in Kenya.

2. Mackerels are a medium of exchange in some U.S. prisons (short video).

3. Yuval Levin reviews The Complacent Class: “Cowen’s book is rich in thought-provoking insights and is a testament to his own voracious curiosity and open-minded intelligence. There is more to it than any summary could hope to capture.”

4. Bob Luddy reviews The Complacent Class in American Spectator: “The Complacent Class defines the daunting challenges of our times.”

5. Facts about blue-footed boobies (NYT).

A new (old) argument against a guaranteed basic income

Later this year, roughly 6,000 people in Kenya will receive regular monthly payments of about a dollar a day, no strings attached, as part of a policy experiment commonly known as basic income.

…In a recent GiveDirectly blog post, the charity’s Kenya-based official, Will Le, explains that refusal rates in East Africa have typically held steady between 4% and 6% in past cash transfer trials. They’ve been especially low in countries like Uganda and Rwanda. In one Kenyan region known as Homa Bay, however, the rates have risen as high as 40%.

…GiveDirectly’s investigations have shown that people who refuse the cash are skeptical. They find it “hard to believe that a new organization like GiveDirectly would give roughly a year’s salary in cash, unconditionally,” Le writes. “As a result, many people have created their own narratives to explain the cash, including rumors that the money is associated with cults or devil worship.”

Here is the full story, the pointer is from the excellent Samir Varma. And here is the GiveDirectly response.

Samir also refers us to this study of why not all states have legalized medical marijuana, here is one result: “If all 50 states had legalized medical marijuana by 2014, according to their estimates, that could translate to savings of $1.5 billion per year in Medicaid spending.”

Tuesday assorted links

1. Shypmate, a new African venture to carry your packages.

2. The problem with cash transfers: the people who don’t get them grow angry.

3. Unprovoked yoghurt attacks the culture that is Dorset.

4. North Korea exports epic art (NYT).

5. Media Metrics, interesting throughout.

Angus Deaton wins the Nobel

Angus Deaton of Princeton University wins the Nobel prize. Working with the World Bank, Deaton has played a huge role in expanding data in developing countries. When you read that world poverty has fallen below 10% for the first time ever and you want to know how we know— the answer is Deaton’s work on household surveys, data collection and welfare measurement. I see Deaton’s major contribution as understanding and measuring world poverty.

Measuring welfare sounds simple but doing it right isn’t easy. How do you compare the standard of living in two different countries? Suppose you simply convert incomes using exchange rates. Sorry, that doesn’t work. Not all goods are traded so exchange rates tend to reflect the prices of tradable goods but a large share of consumption is on hard-to-trade services. The Balassa-Samuelson effect tells us that services will tend to be cheaper in poorer countries (I always get a haircut when in a poor country but I don’t expect to get a great deal on electronics). As a result, comparing standards of living using exchange rates will suggest that developing countries are poorer than they actually are. A second problem is the cheese problem. Americans consume a lot of cheese, the Chinese don’t. Is this because the Chinese are too poor to consume cheese or because tastes differ? How you answer this question makes a difference for understanding welfare. A third problem is the warring supermarkets problem. Two supermarkets each claim that they have the lowest prices and they are both right! How is this possible? Consumers at supermarket A buy more of what is cheap at A and less of what is expensive at A and vice-versa for B. Thus, it would cost more to buy the A basket at store B and it would also cost more to buy the B basket at store A! So which supermarket is better? Comparing standards of living across countries isn’t easy and then you want to make these comparisons consistently over time as well! Deaton, working especially with the World Bank, helped to construct price indices for all countries that measure goods and services and he showed how to use these to make theoretically appropriate comparisons of welfare. Deaton’s presidential address to the American Economic Association in 2010 covers many of these issues.

I see Deaton’s work on world poverty as a tour de force, he made advances in theory, he joined with others to take the theory to the field to make measurements and he used the measurements to draw attention to important issues in the world.

Earlier in his career, Deaton developed tools to bring theory to data on consumption. A key contributions is the Almost Ideal Demand System. We all know that demand curves slope down which means that a fall in the price of the good in question increases the quantity demanded but in fact economic theory says that the demand for good X depends not just on the price of good X but at least potentially on the prices of all other goods. If we want to estimate how a change in policy will influence people’s choices we need to allow demand curves to interact in potentially many ways but we still want to constrain those reactions according to economic theory. In addition, economic theory tells us that an individual’s demand curve slopes down but it doesn’t necessarily imply that the aggregation of individual demand curves must slope down. Aggregation is tricky! The Almost Ideal Demand system, due initially to Deaton and Muellbauer, in 1980 and further developed since then shows how we can estimate demand systems on aggregates of consumers while still preserving and testing the constraints of economic theory.

The study of consumption leads naturally to the study of savings, consumption in future periods. Here we have Keynes’s famous propensity to consume theory (consumption is a fraction of current income), Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis (consumption is a fraction of estimated lifetime income), Modigliani’s Life Cycle Hypothesis (borrow young, save when middle aged, dissave when old). Robert Hall, building on the work of Ramsey, showed in the 1970s that rational expectations implies the famous Euler equation that bedevils graduate students, which shows that suitably discounted changes in marginal utilities should follow a random walk. Deaton played a big role in testing the new theories, mostly finding them wanting.

Deaton’s book, The Great Escape, on growth, health and inequality is accessible and a good read. A controversial aspect of this work is that Deaton falls squarely into the Easterly camp (Deaton’s review of Tyranny of Experts is here) in thinking that foreign aid has probably done more harm than good.

Here is Deaton on foreign aid:

Unfortunately, the world’s rich countries currently are making things worse. Foreign aid – transfers from rich countries to poor countries – has much to its credit, particularly in terms of health care, with many people alive today who would otherwise be dead. But foreign aid also undermines the development of local state capacity.

This is most obvious in countries – mostly in Africa – where the government receives aid directly and aid flows are large relative to fiscal expenditure (often more than half the total). Such governments need no contract with their citizens, no parliament, and no tax-collection system. If they are accountable to anyone, it is to the donors; but even this fails in practice, because the donors, under pressure from their own citizens (who rightly want to help the poor), need to disburse money just as much as poor-country governments need to receive it, if not more so.

What about bypassing governments and giving aid directly to the poor? Certainly, the immediate effects are likely to be better, especially in countries where little government-to-government aid actually reaches the poor. And it would take an astonishingly small sum of money – about 15 US cents a day from each adult in the rich world – to bring everyone up to at least the destitution line of a dollar a day.

Yet this is no solution. Poor people need government to lead better lives; taking government out of the loop might improve things in the short run, but it would leave unsolved the underlying problem. Poor countries cannot forever have their health services run from abroad. Aid undermines what poor people need most: an effective government that works with them for today and tomorrow.

One thing that we can do is to agitate for our own governments to stop doing those things that make it harder for poor countries to stop being poor. Reducing aid is one, but so is limiting the arms trade, improving rich-country trade and subsidy policies, providing technical advice that is not tied to aid, and developing better drugs for diseases that do not affect rich people. We cannot help the poor by making their already-weak governments even weaker.

Here is Tyler’s post on Deaton.

Addendum: Chris Blattman offers a very good perspective and appreciation.

Doing Good Better

William MacAskill is that rare beast, a hard-headed, soft-hearted proponent of saving the world. His excellent new book, Doing Good Better, is a primer on the effective altruism movement.

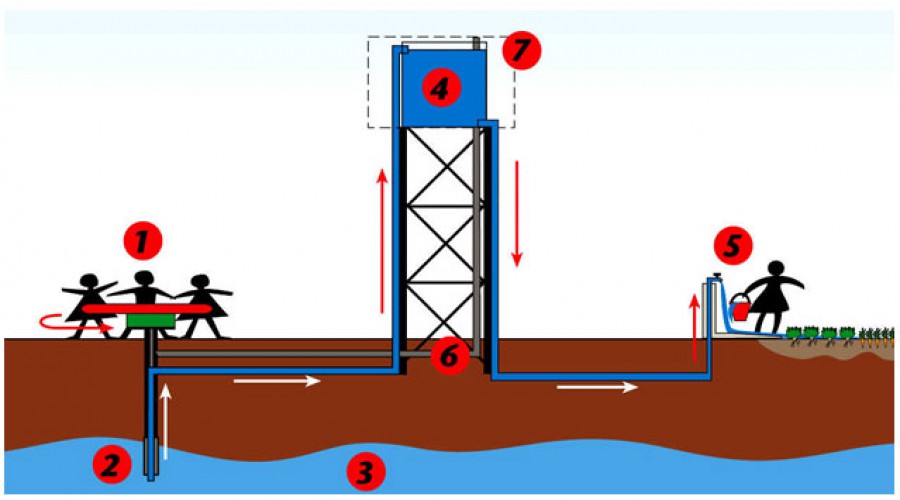

Doing Good Better opens, just as you would expect, with an uplifting story of a wonderful person with a brilliant idea to save the world. The PlayPump uses a merry-go-round to pump water. Fun transformed into labor and life saving clean water! The energetic driver of the idea quits his job and invests his life in the project. Africa! Children on merry-go-rounds! Innovation! What could be better? It’s the perfect charitable meme and the idea attracts millions of dollars of funding from celebrities like Steve Case, Jay-Z, Laura Bush and Bill Clinton.

Doing Good Better opens, just as you would expect, with an uplifting story of a wonderful person with a brilliant idea to save the world. The PlayPump uses a merry-go-round to pump water. Fun transformed into labor and life saving clean water! The energetic driver of the idea quits his job and invests his life in the project. Africa! Children on merry-go-rounds! Innovation! What could be better? It’s the perfect charitable meme and the idea attracts millions of dollars of funding from celebrities like Steve Case, Jay-Z, Laura Bush and Bill Clinton.

Then MacAskill subverts the narrative and drops the bomb:

…despite the hype and the awards and the millions of dollars spent, no one had really considered the practicalities of the PlayPump. Most playground merry-go-rounds spin freely once they’ve gained sufficient momentum–that’s what makes them fun. But in order to pump water, PlayPumps need constant force, and children playing on them would quickly get exhausted.

The women whose labor was supposed to be saved end up pushing the merry-go-round themselves, which they find demeaning and more exhausting than using a hand-pump. Moreover, the device is complicated and requires extensive maintenance that cannot be done in the village. The PlayPump is a disaster.

MacAskill, however, isn’t interested in castigating donors for their first-world hubris. MacAskill, a frugal Scottish philosopher, doesn’t like waste. Money, time and genuine goodwill are wasted in poorly-conceived charitable efforts and when lives are at stake that kind of waste is offensive. MacAskill, however, is convinced that a hard-headed approach–randomized trials, open-data, careful investigation of effectiveness–can do better. As MacAskill puts it:

When it comes to helping others, being unreflective often means being ineffective.

Of course, there are systematic problems with charitable giving. Most importantly, the feedback mechanism is never going to work as well when people are buying something to be consumed by others (as Milton Friedman explains). That problem, however, doesn’t explain why people do invest large amounts of money and their own time on wasteful projects. A large part of the problem is cultural. MacAskill asks us to consider the following thought experiment:

Imagine, for example, that you’re walking down a commercial street in your hometown. An attractive and frightening enthusiastic young woman nearly assaults you in order to get you stop and speak with her. She clasps a tablet and wears a T-shirt displaying the words, Dazzling Cosmetics…she explains that she’s representing a beauty products company that is looking for investment. She tells you about how big the market for beauty products is, and how great the products they sell are, and how because the company spends more than 90 percent of its money on making the products and less than 10 percent on staff, distribution, and marketing, the company is extremely efficient and therefore able to generate an impressive return on investment. Would you invest?

MacAskill says “Of course, you wouldn’t…you would consult experts…which is why the imaginary situation, I described here never occurs” Actually it’s even worse than that because what he describes does occur. It’s what the boiler rooms do to sell stocks (ala the Wolf of Wall Street). Thus, charities raise money using precisely the techniques that in other contexts are widely regarded as deceitful, disreputable and preying on the weak. Once you have seen how peculiar our charitable institutions are, it’s difficult to unsee.

Fortunately, effective altruism doesn’t require Mother Theresa-like levels of altruism or Spock-like level of hard-headedness. What is needed is a cultural change so that people become proud of how they give and not just how much they give. Imagine, for example, that it becomes routine to ask “How does Givewell rate your charity?” Or, “GiveDirectly gives poor people cash–can you demonstrate that your charity is more effective than cash?” The goal is not the questioning. The goal is to give people the warm glow when they can answer.

Nerd Altruism is Becoming Cool!

GiveDirectly, the non-profit started by economists that gives money directly to the poor in the developing world, has grown tremendously in recent years and Bill Gross, the billionaire bond investor and now major philanthropist, just announced that he is interested in the model:

More recently, Gross said he’s taken an interest in GiveDirectly, an organization that makes targeted donations via mobile payments to the extremely poor in Africa.

“Most Africans have cell phones, which is hard to believe,” Gross said in the interview. “So if you can do that and contribute $25 or $50 to someone in Uganda that of course you haven’t met, that’s almost as good as outperforming the market.”

It’s exciting to see randomized trials, measurement and data science applied to philanthropy. Groups like GiveDirectly, GiveWell and The Center for Effective Altruism are creating a new culture of giving, they are making Nerd Altruism cool. We have a long way to go but it says something when billionaires are mocked for giving millions to Yale. In contrast, entrepreneurs like Dustin Moskovitz, Elon Musk and Bill Gates are making it cool to evaluate charities with the same rigor that business people use to evaluate business investments.

Here’s an interview with Paul Niehaus, one of the founders of GiveDirectly.

Give Directly

Here is Tyler summarizing the principles of charitable giving:

1. Cash is often the best form of aid.

2. Give to those who are not expecting it, and,

3. Don’t require the recipients to do anything costly to get the money.

Loyal readers will recall that Tyler followed through on his advice by sending money to random people in India, as suggested by MR readers (see also here).

A new charity is formalizing Tyler’s system and reducing the transaction cost of efficient donation. GiveDirectly takes donations over the web, locates poor households in Kenya using people on the ground, and then transfers money directly to the recipient’s cell phone (even very poor households typically have cell phones but GiveDirectly provides SIM cards for those who do not.) Transactions costs are low, just 10%.

You will not be surprised to learn that the CEO and founders and are all economists (one MBA/MPA). All the founders also have extensive experience in development. A randomized control trial is under way to evaluate the program.

Transfers, following point #3, are unconditional. The founders write:

GiveDirectly intentionally provides unconditional, rather than conditional, cash transfers. We do this for three reasons. First, empowering the poor to make their own decisions advances our core value of respect. Second, it lets recipients purchase the things they need most, enhancing impact. Third, imposing conditions on the use of funds requires that costly monitoring and enforcement structures be put in place. One detailed estimate put the administrative costs of a conditional cash transfer scheme at 63% of the transfers made over the first three years of the program (Caldes & Maluccio 2005).

Points one and three are excellent. The second point is a bit disengenous, yes it lets recipients purchase they things they need but it also lets recipients purchase alcohol, cigarettes and prostitutes. Even in poor countries, a substantial amount of poverty is caused by poor choices. Still, there is no special reason to think that cash grants will increase the proportion of money spent on “bad goods.” Cash grants could even reduce bad-goods spending. Some people drink to escape depressing circumstances, for example, so if you make things less depressing, drinking can fall. Moreover, even if you give people housing, health care, or food (stamps!) it’s not so easy to get around bad-goods spending because money is fungible. Thus, I have no problem with donating cash.

Indeed, Tyler and I wish to encourage experimentation in charity and we have therefore made a donation to GiveDirectly.

Addendum: Givewell, our favorite charity evaluator, says GiveDirectly is too new to evaluate but they like the idea and they note that GiveDirectly has been unusually forthright in providing them with advance plans on evaluation.