Results for “jonathan haidt” 37 found

My contentious Conversation with Jonathan Haidt

Here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is the episode summary:

But might technological advances and good old human resilience allow kids to adapt more easily than he thinks?

Jonathan joined Tyler to discuss this question and more, including whether left-wingers or right-wingers make for better parents, the wisest person Jonathan has interacted with, psychological traits as a source of identitarianism, whether AI will solve the screen time problem, why school closures didn’t seem to affect the well-being of young people, whether the mood shift since 2012 is not just about social media use, the benefits of the broader internet vs. social media, the four norms to solve the biggest collective action problems with smartphone use, the feasibility of age-gating social media, and more.

It is a very different tone than most CWTs, most of all when we get to social media. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: There are two pieces of evidence — when I look at them, they don’t seem to support your story out of sample.

HAIDT: Okay, great. Let’s have it.

COWEN: First, across countries, it’s mostly the Anglosphere and the Nordic countries, which are more or less part of the Anglosphere. Most of the world is immune to this, and smartphones for them seem fine. Why isn’t it just that a negative mood came upon the Anglosphere for reasons we mostly don’t understand, and it didn’t come upon most of the rest of the world? If we’re differentiating my hypothesis from yours, doesn’t that favor my view?

HAIDT: Well, once you look into the connections and the timing, I would say no. I think I see what you’re saying now, but I think your view would say, “Just for some reason we don’t know, things changed around 2012.” Whereas I’m going to say, “Okay, things changed around 2012 in all these countries. We see it in the mental illness rates, especially of the girls.” I’m going to say it’s not just some mood thing. It’s like (a), why is it especially the girls? (b) —

COWEN: They’re more mimetic, right?

HAIDT: Yes, that’s true.

COWEN: Girls are more mimetic in general.

HAIDT: That’s right. That’s part of it. You’re right, that’s part of it. They’re just much more open to connection. They’re more influenced. They’re more subject to contagion. That is a big part of it, you’re right. What Zach Rausch and I have found — he’s my lead researcher at the After Babel Substack. I hope people will sign up. It’s free. We’ve been putting out tons of research. Zach has really tracked down what happened internationally, and I can lay it out.

Now I know the answer. I didn’t know it two months ago. The answer is, within countries, as I said, it’s the people who are conservative and religious who are protected, and the others, the kids get washed out to sea. Psychologically, they feel their life has no meaning. They get more depressed. Zach has looked across countries, and what you find in Europe is that, overall, the kids are getting a little worse off psychologically.

But that hides the fact that in Eastern Europe, which is getting more religious, the kids are actually healthier now than they were 10 years ago, 15 years ago. Whereas in Catholic Europe, they’re a little worse, and in Protestant Europe, they’re much worse.

It doesn’t seem to me like, oh, New Zealand and Iceland were talking to each other, and the kids were sharing memes. It’s rather, everyone in the developed world, even in Eastern Europe, everyone — their kids are on phones, but the penetration, the intensity, was faster in the richest countries, the Anglos and the Scandinavians. That’s where people had the most independence and individualism, which was pretty conducive to happiness before the smartphone. But it now meant that these are the kids who get washed away when you get that rapid conversion to the phone-based childhood around 2012. What’s wrong with that explanation?

COWEN: Old Americans also seem grumpier to me. Maybe that’s cable TV, but it’s not that they’re on their phones all the time. And you know all these studies. If you try to assess what percentage of the variation in happiness of young people is caused by smartphone usage — Sabine Hossenfelder had a recent video on this — those numbers are very, very, very small. That’s another measurement that seems to discriminate in favor of my theory, exogenous mood shifts, rather than your theory. Why not?

Very interesting throughout, recommended. And do not forget that Jon’s argument is outlined in detail in his new book, titled The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

What should I ask Jonathan Haidt?

Yes, I will be doing another Conversation with him. Here is my previous Conversation with him, almost eight years ago. As many of you will know, Jonathan has a new book coming out, namely

My conversation with Jonathan Haidt

This one is transcript and podcast only, no video, and we will be doing some more in that format. Jonathan was in top form, here are a few bits:

COWEN: If we get to a very fundamental question — left‑wing individuals and right‑wing individuals, and let’s take, for now, only America. As people, in other ways, how different do you think they are?

Or, is it just there are these semi‑accidental triggers which have set off certain modules in the left‑wingers and different modules in the right‑wingers, but otherwise they’re going to dress the same, they’re going to treat their spouses the same way, or not? Are they fundamentally different?

HAIDT: Not fundamentally different, but different in predispositions. The most important finding in psychology in the last 50 to 100 years, I would say, is the finding that everything you can measure is heritable. The heritability coefficients vary between 0.3 and 0.6, or 30 to 60 percent of the variance, under some assumptions, can be explained by the genes. It’s the largest piece of variance we can explain.

If you and I were twins separated at birth and raised in different families, our families would pick which religions we were raised in and they would pick how often we go to church or synagogue, but once we’re out on our own, we’re going to both converge on our brain’s natural level of religiosity.

Same with politics, whether you’re on the right or left is not determined by your genes, but you’re predisposed.

And:

COWEN: If you’re in a swing state in, say, proverbial southern Ohio and in a natural setting you meet a person. With what probability do you think you can guess or forecast if they’re left‑wing or right‑wing? Even-up would be 0.5.

HAIDT: Probably 0.58, 0.57. People are incredibly variable.

And:

COWEN: Would it be a partial test of your theory if we looked at a lot of different cultures and asked, “Who are the people who dress neatly and who have a lot of calendars and stamps?” to measure whether those were typically the conservatives?

HAIDT: Yes, that would be a test.

And:

COWEN: For gay individuals, maybe not all minorities, but many minorities this is very much a positive thing. If morality is fundamentally so nonrational or arational in some key ways, is it not the case we’re always either undershooting or overshooting the target, that we can never hit it just right?

Maybe for America to be more tolerant, you need the norms to be quite crude and blunt, and overstated, and we get this political correctness. Yes it’s bad, but maybe it’s less bad then when we used to undershoot the target?

Jonathan had a good answer but it is too long to excerpt.

COWEN: Let’s say you’re Brown or Yale, and students set up a lacrosse team, and they call it the Brown Redskins, and they do some rituals which offend some people. No matter what the intent would be, should Brown or Yale step in and say, “You can’t do that?”

HAIDT: There’s a big, big line between saying, “Brown or Yale should step in and tell people what they can’t — .” In general I think no, in general the idea — .

COWEN: No they shouldn’t step in?

HAIDT: They should not step in. We should be extremely limited when we say that authorities can step in and change things. The very fact of doing that encourages microaggression culture, encourages students to orient themselves towards appealing to these authorities. The point of the microaggression article is young people these days have become moral dependents.

And:

COWEN: Let me try another analogy on you. You mentioned the army, but take private corporations, and Brown and Yale are in a sense private corporations. Harvard was originally. I wouldn’t call them restrictions on free speech, I think that’s the wrong phrase, but if one’s going to use the phrase that way, there are numerous restrictions on free speech within companies, at the work place.

If you went to the water cooler and said a number of offensive things, you would be asked to stop and eventually fired, and I don’t see anything wrong with that. So if we think of Brown, Yale, or Harvard as like a normal company, isn’t there still even with all the nonsense, a lot more free speech on campus than in actual companies?

HAIDT: Yes, and there should be. Again, a company is organized to be effective in the world. Just like the army where their priority is unit cohesion, in a company your goal isn’t to encourage everyone to express their values and criticize each other, your goal is to get them to work together.

There is much much more, including on LSD, Sigmund Freud (overrated or underrated), Cecil Rhodes, how Jonathan would change undergraduate admissions, whether behavioral economics is realizing its full potential, Adam Smith, antiparsimonialism, the replication crisis in psychology, and whether Jonathan enjoys eating insects.

What should I ask Jonathan Haidt?

I will be doing a Conversations with Tyler with Jonathan Haidt, but with no public event and no video, transcript and podcast only.

What should I ask him?

Jonathan Haidt seeks a hire

From an email, via Dan Klein:

We are seeking a talented and experienced researcher with some tech skills to help run two projects that use social science research to improve major American institutions. Your main job would be research director for HeterodoxAcademy.org, a collaboration of social scientists trying to increase viewpoint diversity in the academy. You would also be part of the team at EthicalSystems.org, a research collaboration that uses behavioral science to “make ethics easy” for businesses.

The ideal candidate will be a recent Ph.D. or ABD in the social sciences with both technological sophistication and excellent writing skills.

To Apply: Send a CV, writing sample, and cover letter explaining why you would be a good fit for the job to Jeremy Willinger, Communications Director, at [email protected].

Jonathan Haidt’s new book

The Righteous Mind: Why People are Divided by Religion and Politics.

Due out Tuesday. I haven’t read it yet, but I have pre-ordered a copy for my Kindle while traveling. Haidt is one of the most important social scientists of our time, here are two relevant links.

For the pointer I thank Arnold Kling.

Here is Haidt on Twitter.

Saturday assorted links

1. “When Lee Jae-hye goes to the United States, she’s 30. When she’s back in South Korea, she’s 32.” (NYT)

2. Review essay on social media and political dysfunction.

3. The deadly accordion wars of Lesotho.

4. Ivanchuk Reviews His Game Against Carlsen, Ignores Air Raid Alert.

5. Jonathan Haidt Lunch with the FT.

6. Interview/podcast/YouTube with Thomas Uhm of Jane Street. Crypto and NFTs too, some unique perspectives, in part a non-crazy person explaining the potential to the doubting Sallies.

The University of Austin

A new university is being founded. Here is part of the statement from its new president, Pano Kanelos:

As I write this, I am sitting in my new office (boxes still waiting to be unpacked) in balmy Austin, Texas, where I moved three months ago from my previous post as president of St. John’s College in Annapolis.

I am not alone.

Our project began with a small gathering of those concerned about the state of higher education—Niall Ferguson, Bari Weiss, Heather Heying, Joe Lonsdale, Arthur Brooks, and I—and we have since been joined by many others, including the brave professors mentioned above, Kathleen Stock, Dorian Abbot and Peter Boghossian.

We count among our numbers university presidents: Robert Zimmer, Larry Summers, John Nunes, and Gordon Gee, and leading academics, such as Steven Pinker, Deirdre McCloskey, Leon Kass, Jonathan Haidt, Glenn Loury, Joshua Katz, Vickie Sullivan, Geoffrey Stone, Bill McClay, and Tyler Cowen [TC: I am on the advisory board].

We are also joined by journalists, artists, philanthropists, researchers, and public intellectuals, including Lex Fridman, Andrew Sullivan, Rob Henderson, Caitlin Flanagan, David Mamet, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Sohrab Ahmari, Stacy Hock, Jonathan Rauch, and Nadine Strossen.

You can follow the school on Twitter here.

My Conversation with Ezra Klein

Here is the audio and transcript. Yes we talked a great deal about Ezra’s new book on polarization, but much more too:

Tyler posed these questions to Ezra and more, including thoughts on Silicon Valley’s intellectual culture, his disagreement with Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, the limits of telecommuting, how becoming a father made him less conservative, his post-kid production function, why Manhattan is overrated, the “cosmic embarrassment” of California’s governance, why he loved Marriage Story, the future of the BBC and PBS, what he learned in Pakistan, and more.

Here is one bit:

COWEN: We would agree that what is called affective negative polarization is way up — professing a dislike of the other side, not wanting your Republican kid to marry a Democratic wife, and so on. But in terms of actual policy polarization, what if someone says, “Well, that’s down,” and they say this: “Well, the main issue in foreign policy today is China.” That’s actually fairly bipartisan. Or if people don’t agree, they don’t disagree by party.

Domestic spending, Social Security, Medicare — no one wants to cut those. That’s actually consensus. The other main issue is how we deal with or regulate tech. America has its own system. It’s happened through the regulators. It’s not really that partisan. One may or may not like it, but again, disagreement about it doesn’t fall along normal party lines.

So the main foreign policy issue, the main substantive social issue — we’re less polarized. And then, domestic spending, it seems, we all mostly agree. Why is that wrong?

KLEIN: I’m not sure it is wrong. Two things I would say about it. One, the word main is doing a lot of work in that argument. The question is, how do you decide what are the main issues? I wouldn’t say domestic regulation of tech is a main issue, for instance. I think it’s important, but compared to things like immigration and healthcare, at least in the way people experience that and think about that — or if you ask them what are their main issues, domestic regulation of tech doesn’t crack the top 10.

And:

COWEN: But again, at any point in time, if positions are shifting rapidly — as they are, say, on trade — if you took all of GDP, even healthcare — that’s what, maybe 18 percent of GDP? But a lot of the system, a lot of people in both parties agree on, even if they disagree on Obamacare. Obamacare is part of that 18 percent. Over what percent of GDP are we more polarized than we used to be, as compared to less polarized? What’s your estimate?

KLEIN: I like that question. Let me try to think about this. I don’t think I have a GDP answer for you, but let me try to give you more of what I think of as a mechanism.

I think a useful heuristic here — people don’t have nearly as strong views on policy qua policy as certainly people like you and I tend to assume they do. The way that Washington, DC, talks about politics is incredibly projection oriented. We talk about politics as if everybody is a political junkie with highly distinct ideologies.

Political scientists have done a lot of polling on this, going all the way back to the 1960s, and it seems something like 20 to 30 percent of the population has what we would think of as a coherent policy-oriented ideology, where things fit together, and they have everything lined up. Most people don’t hold policy positions all that strongly.

What happens is that they do hold — to the extent they’re involved in politics — identity strongly, political affiliations quite strongly. They know who is on their side and who isn’t.

The pattern that I see here, again and again, is that when things are out of the spotlight, when they are not being argued about, when they are not the thing that the parties are disagreeing about, they’re actually quite nonpolarized. You’ll sit there in rooms of experts. There’ll be a panel here, George Mason, whatever it might be, and everybody will have some good ideas about how you can make the system better for everyone.

Then what will happen is, the Eye of Sauron of the American political system will turn towards whatever the policy issue is. Maybe it’s Obamacare, maybe it’s climate change. Remember, climate change was not that polarized 15–20 years ago. John McCain had a big cap-and-trade plan in his 2008 platform —

And:

COWEN: If you could engineer your own political temperament, would you change it from how it is? Mostly, we’re stuck with what we’ve got, I would say, but if you could press the button — more passionate, less passionate, something else? Goldilocks?

KLEIN: I think I like my political temperament. Probably for the era of politics we’re moving into, and for my job, it would almost be better to be of a more conflict-oriented temperament than I am. I think that we are moving into something that, at least in the short term, is rewarding or is going to reward those who really like getting in fights all the time, and I don’t like that.

I’m more consensus oriented. I like hearing people out. I probably have a little bit more of a moderate temperament in that way. But I wouldn’t really change that about myself. I think it’s a shame that so much of politics happens on Twitter now, but that’s the way it is. I wouldn’t change me to operate to that.

Recommended, and again here is Ezra’s new book on polarization.

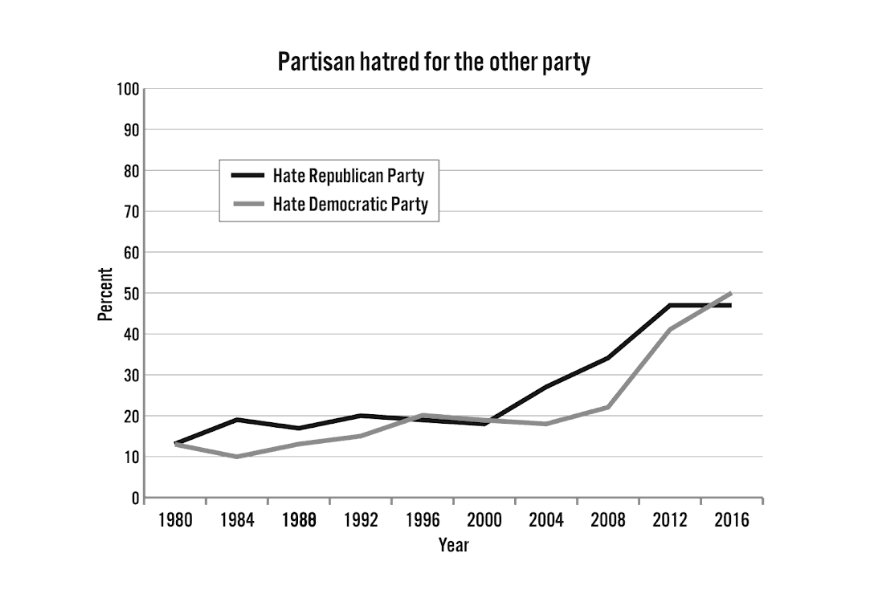

Partisan hatred, a short history thereof

Via Hetherington and Weiler, via Jonathan Haidt.

Via Hetherington and Weiler, via Jonathan Haidt.

*The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure*

That is the new book by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, due out September 4, you can now pre-order it here. Here is my earlier Conversation with Jonathan.

*Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America*

Acclaimed legal scholar, Harvard Professor, and New York Times bestselling author Cass R. Sunstein brings together a compelling collection of essays by our nation’s brightest minds across the political spectrum—including Eric Posner, Tyler Cowen, Noah Feldman, Jack Goldsmith, and Martha Minow—who ponder the question: Can authoritarianism take hold here?

With the election of Donald J. Trump, many people on both the left and right feared that America’s 240-year-old grand experiment in democracy was coming to an end, and that Sinclair Lewis’ satirical novel, It Can’t Happen Here, written during the dark days of the 1930s, could finally be coming true.

Is the democratic freedom that the United States symbolizes really secure? Can authoritarianism happen in America? Sunstein queried a number of the nation’s leading thinkers. In Can It Happen Here? he gathers together their diverse perspectives on these timely questions and more.

In this thought-provoking collection of essays, these distinguished thinkers and theorists explore the lessons of history, how democracies crumble, how propaganda works, and the role of the media, courts, elections, and “fake news” in the modern political landscape—and what the future of the United States may hold.

Due out in March, pre-order here. The book also has Jon Elster, Timur Kuran, and Jonathan Haidt, dare I call it self-recommending?

The Viewpoint Diversity Experience

That is a new project by Jonathan Haidt and the Heterodox Academy, here is a partial summary:

Heterodox Academy announces a simpler, easier, and cheaper alternative: The Viewpoint Diversity Experience. It is a resource created by the members of Heterodox Academy that takes students on a six-step journey, at the end of which they will be better able to live alongside—and learn from—fellow students who do not share their politics.

It’s a very flexible resource that can be completed by individuals before they arrive on campus, presented in an orientation-week workshop, or expanded into a full semester course that students can take during their first year. (It could also be helpful in high schools, companies, religious congregations, and any other organizations that are experiencing sharp political divisions and conflicts.)

…The site is still under development: we welcome feedback and criticism. We particularly seek out professors, high school teachers, and diversity trainers who will partner with us to develop detailed teaching plans and activities. We will have a larger public launch of the project in August, complete with assessment materials that will allow you to measure whether the curriculum actually increased political knowledge and cross-partisan understanding.

Do click on the site itself for a fuller explanation, and please help out if you can.

*How Emotions are Made*

That is the new book by Lisa Feldman Barrett, and the subtitle is The Secret Life of the Brain. I am not well-informed in this area, but here were some of my takeaways:

1. The previous dominant view of emotions, sometimes associated with Paul Ekman, suggests that emotions are a natural and pre-programmed response to changes in the environmental. Imagine a wolf snarling if a potentially hostile animal crosses its path.

2. According to Barrett, the expressions of human emotions are better understood as being socially constructed and filtered through cultural influences: “”Are you saying that in a frustrating, humiliating situation, not everyone will get angry so that their blood boils and their palms sweat and their cheeks flush?” And my answer is yes, that is exactly what I am saying.” (p.15) In reality, you are as an individual an active constructor of your emotions. Imagine winning a big sporting event, and not being sure whether to laugh, cry, scream, jump for joy, pump your fist, or all of the above. No one of these is the “natural response.”

3. Immigrants eventually acculturate emotionally into their new societies, or at least one hopes: “Our colleague Yulia Chentsova Dutton from Russia says that her cheeks ached for an entire year after moving to the United States because she never smiled so much.” (p.149)

3b. There is also this: “My neighbor Paul Harris, a transplanted emotion researcher from England, has observed how American academics are always excited by scientific puzzles — a high arousal, pleasant feeling — but never curious, perplexed, or confused, which are low arousal and fairly neutral experiences that are more familiar to him.” (p.149)

3c. It can be very hard to read the emotions on faces across cultures, and Barrett is opposed to what she calls “emotional essentialism.”

3d. From her NYT piece: “My lab analyzed over 200 published studies, covering nearly 22,000 test subjects, and found no consistent and specific fingerprints in the body for any emotion. Instead, the body acts in diverse ways that are tied to the situation.”

4. One reason for my interest in this work is that it potentially provides microfoundations for thinking about how “culture” matters for economic and other social outcomes. It also helps explain the importance of peers for education, and for that matter for religious experience, in the same outlined by William James. It may help explain Jonathan Haidt-related research results about disgust. It also provides potential microfoundations for explaining how individuals with different cognitive profiles (autism, Williams and Rett, Down syndrome, etc.), will, for related reasons, process some emotions differently too, although Barrett does not explore this route.

5. The concepts of a “control network” and an “introceptive network” are explained and presented as critical for controlling emotions, and in terms of the broader theory the mind is fundamentally about prediction. From my outsider point of view, the emphasis on prediction seems a little too strong. For instance, there may also be a need to make ourselves predictable to others, even if that lowers out own ability to predict.

6. “Affect is not just necessary for wisdom; it’s also irrevocably woven into the fabric of every decision.” And she refers repeatedly to: “…your inner, loudmouthed, mostly deaf scientist who views the world through affect-colored glasses.”

7. I found the chapter on animals the most problematic for the broader thesis. It seems to me that the Ekman view really does handle the snarling wolf pretty well and that is a case of emotional essentialism. Barrett tries to outline how humans are different from other mammals in this regard, but I came away thinking the truth might be a mix of her view and the Ekman view. It seems to me that some version of emotional essentialism provides an overarching constraint on the social construction of emotions, and furthermore there might be some regulating process at a higher level, mixing in varying proportions of essentialist and social construction features of emotional responses.

My apologies for any errors or misunderstandings in this presentation!

I can say this book is very well-written, it covers material not found in other popular science books, and it comes strongly recommended by Daniel Gilbert. I asked a friend of mine who researches directly in this area, and she reports that Barrett’s view is in fact taken seriously by other researchers, it has been very influential, and it is has been gaining in popularity. Make of that what you will.

Here is a very useful interview with the author. Here is her Northeastern home page. I recall reading somewhere that she is a big fan of chocolate, but can no longer find that link. Should I laugh, cry, or shrug my shoulders in response to that failure?

I thank Benjamin Lyons for the pointer to this work.