Results for “labor mobility” 73 found

Gangs, Labor Mobility and Development

We study how two of the world’s largest gangs—MS-13 and 18th Street—affect economic development in El Salvador. We exploit the fact that the emergence of these gangs was the consequence of an exogenous shift in American immigration policy that led to the deportation of gang leaders from the United States to El Salvador. Using a spatial regression discontinuity design, we find that individuals living under gang control have significantly less education, material wellbeing, and income than individuals living only 50 meters away but outside of gang territory. None of these discontinuities existed before the emergence of the gangs. The results are confirmed by a difference-in-differences analysis: after the gangs’ arrival, locations under their control started experiencing lower growth in nighttime light density compared to areas without gang presence. A key mechanism behind the results is that, in order to maintain territorial control, gangs restrict individuals’ freedom of movement, affecting their labor market options. The results are not determined by exposure to violence or selective migration from gang locations. We also find no differences in public goods provision.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Nikita Melnikov, Carlos Schmidt-Padilla, and Maria Micaela Sviatschi.

Why is labor mobility slowing in America?

There is a new and quite interesting paper on this topic, by Kyle Mangum and Patrick Coate:

This paper offers an explanation for declining internal migration in the United States motivated by a new empirical fact: the mobility decline is driven by locations with typically high rates of population turnover. These “fast” locations were the Sunbelt centers of population growth during the twentieth century. The paper presents evidence that as spatial population growth converged, residents of fast locations were subject to rising levels of preference for home. Using a novel measure of home attachment, the paper develops and estimates a structural model of migration that distinguishes moving frictions from home utility. Simulations quantify the role of multiple explanations of the mobility decline. Rising home attachment accounts for nearly half of the decline, roughly as large as the effect of an aging population, and is consistent with the spatial pattern. The implication is recent declining migration is a long run result of population shifts of the twentieth century.

For the pointer I thank the excellent Tyler Ransom.

Why is labor mobility in India so low?

From Kaivan Munshi and Mark Rosenzweig, here is the puzzle:

It follows that the real wage gap [rural to urban] in India is at least 16 percentage points larger than it is in China and Indonesia. There is evidently some friction that prevents rural Indian workers from taking advantage of more remunerative job opportunities in the city.

Indian migration to the cities is much lower than for China or Indonesia. Here is part of the answer:

The explanation that we propose for India’s low mobility is based on a combination of well-functioning rural insurance networks and the absence of formal insurance, which includes government safety nets and private credit.

…In rural India, informal insurance networks are organized along caste lines. The basic marriage rule in India (which recent genetic evidence indicates has been binding for nearly two thousand years) is that no individual is permitted to marry outside the sub-caste or jati (for expositional convenience, we use the term caste interchangeably with sub-caste). Frequent social interactions and close ties within the caste, which consists of thousands of households clustered in widely dispersed villages, support very connected and exceptionally extensive insurance networks.

Households with members who have migrated to the city will have reduced access to rural caste networks…

I believe “deficient infrastructure” and “lack of good manufacturing jobs” should be a bigger part of that answer, but nonetheless an interesting question and discussion. Might the multiplicity of languages in India be a factor too? Here is my earlier argument that Indian cities may be undercrowded.

For the pointer I thank the excellent Samir Varma.

Why is American labor mobility falling?

The first [reason] is that the mix of jobs offered in different parts of America has become more uniform. The authors compute an index of occupational segregation, which compares the composition of employment in individual places with the national profile. Over time, their figures show, employment in individual markets has come to resemble more closely that in the nation as a whole.

This homogenisation reflects the rising importance of “non-tradable” work…

Yet a more uniform job distribution alone cannot account for falling mobility. As Messrs Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl point out, mobility has fallen for manufacturers, where jobs are more dispersed, as well as for service-sector workers. What is more, if workers know that they can find jobs they want in different places, they may become more willing to move for other reasons—to be by the coast, for example, or to savour a particular music scene. Yet survey data reveal that moves for these other reasons have not risen. The authors suggest another force is also reducing migration: the plummeting cost of information.

…In recent decades, however, it has become much easier to learn about places without moving house. Deregulated airlines and innovative online-travel services have slashed travel costs, allowing people to visit and assess different markets without moving. The web makes it vastly easier to study every aspect of a potential new home, from the quality of its apartment stock to the surliness of its baristas, all without leaving home. Falling mobility isn’t simply caused by labour-market homogenisation, the authors argue, but also by greater efficiency. People are able to find the right job in the ideal city in fewer hops than before.

New evidence that being underwater on your house limits labor mobility

Rortybomb has long argued there is no significant effect. I’ve never had a horse in this race, in any case here are new results from Plamen Nenov, on the job market from MIT:

The present paper studies the impact of a housing bust on regional labor reallocation and the labor market. I document a novel empirical fact, which suggests that, by increasing the fraction of households with negative housing equity, a housing bust hinders interregional mobility. I then study a multi-region economy with local labor and housing markets and worker reallocation. The model can account for the positive co-movement of relative house prices and unemployment with gross out-migration and negative co-movement with in-migration observed in the cross section of states. A housing bust creates debt overhang for some workers, which distorts their migration decisions and increases aggregate unemployment in the economy. This adverse effect is amplified when regional slumps are particularly deep as in the recent U.S. recession. In a calibrated version of the model, I find that the regional reallocation effect of the housing bust can account for between 0.2 and 0.5 percentage points of aggregate unemployment and 0.4 and 1.2 percentage points of unemployment in metropolitan areas experiencing deep local recessions in 2010. Finally, I study the labor market effects of two policies proposed for addressing the U.S. mortgage crisis.

I’m still not taking sides here, just fyi.

Denmark has as much labor mobility as the United States

According to Daniel Schwammenthal (WSJ, April), about 30 percent of the Danish work force changes jobs each year. There are few guarantees of job security, and the Danish government spends a great deal of worker retraining. These training recipients face strong moral and financial pressure to take jobs which are offered to them. There is also a new NBER paper on the miracle of the Danish labor force.

…we briefly describe some key features of the labor market in Denmark, some of which contribute to the Danish labor markets behaving quite differently from those in many other European countries…We show that mobility is about as high, or even higher, as in the highly fluid U.S. labor market. Finally, we describe and examine the wage structure between and within firms and changes therein since 1980, especially with an eye on possible impacts of the trend towards a more decentralized wage determination. The shift towards decentralized wage bargaining has coincided with deregulation and increased product market competition. The evidence is, however, not consistent with stronger competition in product markets eroding firm-specific rents. Hence, the prime suspect is the change in wage setting institutions.

Starting in the late 1980s, wage bargaining in Denmark became increasingly decentralized, and that is considered to be a major reason for Danish labor market successes.

The labor market mismatch model

This paper studies the cyclical dynamics of skill mismatch and quantifies its impact on labor productivity. We build a tractable directed search model, in which workers differ in skills along multiple dimensions and sort into jobs with heterogeneous skill requirements. Skill mismatch arises because of information frictions and is prolonged by search frictions. Estimated to the United States, the model replicates salient business cycle properties of mismatch. Job transitions in and out of bottom job rungs, combined with career mobility, are key to account for the empirical fit. The model provides a novel narrative for the scarring effect of unemployment.

That is from the new JPE, by Isaac Baley, Ana Figueiredo, and Robert Ulbricht. Follow the science! Don’t let only the Keynesians tell you what is and is not an accepted macroeconomic theory.

Has intergenerational mobility finally been shown to have declined?

If you recall, Robert D. Putnam, in his last book, expressed surprise that Chetty and Hendren, et.al. (2014) did not find evidence of a decline in intergenerational mobility. Putnam predicted that researchers would find such evidence soon enough. After all, it seems the returns to education have been rising, geographic mobility has been falling, market concentration is up slightly, life expectancy is behaving in funny ways, and regional disparities seem to have grown. Chetty and Grusky, et.al. (2016) seemed to paint a more pessimistic picture than did his work from a few years ago, and now we have a new paper by Jonathan Davis and Bhashkar Mazumder:

We demonstrate that intergenerational mobility declined sharply for cohorts born between 1942 and 1953 compared to those born between 1957 and 1964. The former entered the labor market prior to the large rise in inequality that occurred around 1980 while the latter cohorts entered the labor market largely afterwards. We show that the rank-rank slope rose from 0.27 to 0.4 and the IGE rose from 0.35 to 0.51. The share of children whose income exceeds that of their parents fell by about 3 percentage points. These findings suggest that relative mobility fell by substantially more than absolute mobility.

So far this seems to be the current version of the final word. The authors also argue, by the way, that Chetty (2016) is somewhat too pessimistic, though correct in suggesting mobility has indeed fallen.

By the way, this seems to be the best link for a download.

Upward Mobility and Discrimination: Asians and African Americans

Asians in America faced heavy discrimination and animus in the early twentieth century. Yet, after institutional restrictions were lifted in the late 1940s, Asian incomes quickly converged to white incomes. Why? In the politically incorrect paper of the year (ungated) Nathaniel Hilger argues that convergence was due to market forces subverting discrimination. First, a reminder about the history and strength of discrimination against Asians:

Foreign-born Asians were barred from naturalization by the Naturalization Act of 1790. This Act excluded Asians from citizenship and voting except by birth, and created the important new legal category of “aliens ineligible for citizenship”…Asians experienced mob violence including lynchings and over 200 “roundups” from 1849-1906 (Pfaelzer, 2008), and hostility from anti-Asian clubs much like the Ku Klux Klan (e.g., the Asiatic Exclusion League, Chinese Exclusion League, Workingmen’s Party of CA), to an extent that does not appear to have any counterpart for blacks in CA history. Both Asians and blacks in CA could not testify against a white witness in court from 1853-73 (People v. Hall, 1853, see McClain, 1984), limiting Asians’ legal defense against white aggression. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” in 1907 barred further immigration of all “laborers” from China and Japan.

…Asians have also faced intense economic discrimination. Many cities and states levied discriminatory taxes and fees on Asians (1852 Foreign Miner’s Tax, 1852 Commutation Tax, 1860 Fishing License, 1862 Police Tax, 1870 “queue” ordinance, 1870 sidewalk ordinance, and many others). Many professional schools and associations in CA excluded Asians (e.g., State Bar of CA), as did most labor unions (e.g., Knights of Labor, American Federation of Labor), and many employers declined to hire Asians well into the 20th century (e.g., Mears, 1928, p. 194-204). From 1913-23, virtually all western states passed increasingly strict Alien Land Acts that prohibited foreign-born Asians from owning land or leasing land for extended periods. Asians also faced laws against marriage to whites (1905 amendment to Section 60 of the CA Civil Code) and U.S. citizens (Expatriation Act 1907, Cable Act 1922). From 1942-46, the US forcibly relocated over 100,000 mainland Japanese Americans (unlike other Axis nationalities, e.g. German or Italian Americans) to military detention camps, in practice destroying a large share of Japanese American wealth. In contrast, blacks in CA were eligible for citizenship and suffrage, were officially (though often not de facto) included in CA professional associations and labor unions that excluded Asians, were not covered by the Alien Land Acts, and were not confined or expropriated during WWII.

Despite this intense discrimination, Asian (primarily Japanese and Chinese) incomes converged to white incomes as early as 1960 and certainly by 1980. One argument is that Asians invested so heavily in education that convergence has been overstated but Hilger shows that convergence occurred conditional on education. Similarly, convergence was not a matter of immigration or changing demographics. Instead, Hilger argues that once institutional discrimination was eased in the 1940s, market forces enforced convergence. As I wrote earlier, profit maximization subverts discrimination by employers:

If the wages of X-type workers are 25% lower than those of Y-type workers, for example, then a greedy capitalist can increase profits by hiring more X workers. If Y workers cost $15 per hour and X workers cost $11.25 per hour then a firm with 100 workers could make an extra $750,000 a year. In fact, a greedy capitalist could earn more than this by pricing just below the discriminating firms, taking over the market, and driving the discriminating firms under.

If that theory is true, however, then why haven’t black incomes converged? And here is where the paper gets into the politically incorrect:

Modern empirical work has indicated that cognitive test scores—interpreted as measures of productivity not captured by educational attainment—can account for a large share of black-white wage and earnings gaps (Neal and Johnson, 1996; Johnson and Neal, 1998; Fryer, 2010; Carruthers and Wanamaker, 2016). This literature documents large black-white test score gaps that emerge early in childhood (Fryer and Levitt, 2013), persist into adulthood, and appear to reflect genuine skills related to labor market productivity rather than racial bias in the testing instrument (Neal and Johnson, 1996). While these modern score gaps

have not been fully accounted for by measured background characteristics (Neal, 2006; Fryer and Levitt, 2006; Fryer, 2010), they likely relate to suppressed black skill acquisition during slavery and subsequent educational discrimination against blacks spanning multiple generations (Margo, 2016).

…A basic requirement of this hypothesis is that Asians in 1940 possessed greater skills than blacks, conditional on education. In fact, previous research on Japanese Americans in CA support this theory. Evidence from a variety of cognitive tests given to students in CA in the early 20th century suggest test score parity of Japanese Americans with local whites after accounting for linguistic and cultural discrepancies, and superiority of Japanese Americans in academic performance in grades 7-12 (Ichihashi, 1932; Bell, 1935).

Hilger supplements these earlier findings with a small dataset from the Army General Classification Test:

…these groups’ cognitive test performance can be studied using AGCT scores in WWII enlistment records from 1943. Remarkably, these data are large enough to compare Chinese, blacks and whites living in CA for these earlier cohorts. In addition, this sample contains enough young men past their early 20s to compare test scores conditional on final educational attainment, which can help to shed light on mechanisms underlying the conditional earnings gap documented above.

Figure XII plots the distribution of normalized test score residuals by race from an OLS regression of test z-scores on dummies for education and age. Chinese Americans and whites have strikingly similar conditional skill distributions, while the black skill distribution lags behind by nearly a full standard deviation. Table VIII shows that this pattern holds separately within broad educational categories. These high test scores of Chinese Americans provide strong evidence that the AGCT was not hopelessly biased against non-whites, as Neal and Johnson (1996) also find for the AFQT (the successor to the AGCT) in more recent cohorts.

From Hilger’s conclusion:

Using a large and broadly representative sample of WWII enlistee test scores from 1943 both on their own and matched to the 1940 census, I document the striking fact that these test scores can account for a large share of the black, but not Asian, conditional earnings gap in 1940. This result suggests that Asians earnings gaps in 1940 stemmed primarily from taste-based or some other non-statistical discrimination, in sharp contrast with the black earnings gap which largely reflected statistical discrimination based on skill gaps inherited from centuries of slavery and educational exclusion. The rapid divergence of conditional earnings between CA-born Asians and blacks after 1940—once CA abandoned its most severe discriminatory laws and practices—provides the first direct empirical evidence in support of the hypothesis of Arrow (1972) and others that competitive labor markets tend to eliminate earnings gaps based purely on taste-based but not statistical discrimination.

Hilger’s other research is here.

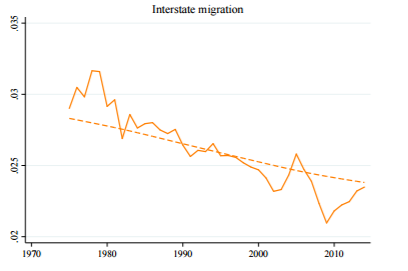

Declining Mobility and Restrictions on Land Use

Mobility has been slowly falling in the United States since the 1980s. Why? One possibility is demographic changes. Older people, for example, are less likely to move than younger people so increases in the elderly population might explain declines in mobility. Mobility has declined, however, for people of all ages. In the 1980s, for example, 3.6% of people aged 25-44 had moved in the last year but in the 2000s only 2.2% of this age group had moved.

(Graph from Molloy, Smith, Trezzi and Wozniak).

(Graph from Molloy, Smith, Trezzi and Wozniak).In fact, mobility has declined within age, gender, race, home ownership status, whether your spouse works or not, income class, and employment status so whatever the cause of declining mobility it has to be big enough to affect large numbers of people across a range of demographics.

My best guess is that the decline in mobility is due to problems in our housing markets (I draw here on an important paper by Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag). It used to be that poor people moved to rich places. A janitor in New York, for example, used to earn more than a janitor in Alabama even after adjusting for housing costs. As a result, janitors moved from Alabama to New York, in the process raising their standard of living and reducing income inequality. Today, however, after taking into account housing costs, janitors in New York earn less than janitors in Alabama. As a result, poor people no longer move to rich places. Indeed, there is now a slight trend for poor people to move to poor places because even though wages are lower in poor places, housing prices are lower yet.

Ideally, we want labor and other resources to move from low productivity places to high productivity places–this dynamic reallocation of resources is one of the causes of rising productivity. But for low-skill workers the opposite is happening – housing prices are driving them from high productivity places to low productivity places. Furthermore, when low-skill workers end up in low-productivity places, wages are lower so there are fewer reasons to be employed and there aren’t high-wage jobs in the area so the incentives to increase human capital are dulled. The process of poverty becomes self-reinforcing.

Why has housing become so expensive in high-productivity places? It is true that there are geographic constraints (Manhattan isn’t getting any bigger) but zoning and other land use restrictions including historical and environmental “protection” are reducing the amount of land available for housing and how much building can be done on a given piece of land. As a result, in places with lots of restrictions on land use, increased demand for housing shows up mostly in house prices rather than in house quantities.

In the past, when a city like New York became more productive it attracted the poor and rich alike and as the poor moved in more housing was built and the wages and productivity of the poor increased and national inequality declined. Now, when a city like San Jose becomes more productive, people try to move to the city but housing doesn’t expand so the price of housing rises and only the highly skilled can live in the city. The end result is high-skilled people living in high-productivity cities and low-skilled people live in low-productivity cities. On a national level, land restrictions mean less mobility, lower national productivity and increased income and geographic inequality.

From my answer on Quora.

Here is my post on occupational licensing and declines in mobility.

Do higher marginal tax rates reduce income mobility?

It seems so, according to the job market paper from Mario Alloza (pdf):

The results obtained suggest that higher marginal tax rates reduce income mobility. Particularly, I find that an increase of one percentage point in the marginal rate is associated with declines of about 0.5-1.3% in the probability of changing deciles of income. A decrease of 7 percentage points in the marginal tax rate (slightly smaller than a standard deviation of non-zero changes in the rates) can account for about a tenth of the average income mobility in a year. The effect of taxes on mobility arises in specifications that consider income distributions both before and after taxes and transfers, suggesting that the impact of taxation on mobility goes beyond redistribution effects. The economic mechanism that induces this impact seems to be related to the labour market incentives created by changes in the tax schedule.

Interestingly, these effects are especially pronounced toward the bottom of the income distribution. If the implied labor supply response seems too high to you, then read some of the recent papers by Karel Mertens. The idea that taxes matter is making a comeback in economics, though I am not sure you would get that impression from most of the economics blogosphere.

Do note the mobility results cover taxes only, and not how the money is spent.

For the pointer I thank Peter Isztin.

Michael Strain’s new jobs agenda and mobility payments

I have been meaning to cover this topic, here is an overview from Reihan. There is one brief version from Strain here. He has many valuable ideas, and the one which has caught my attention is this:

Offering relocation vouchers to the long-term unemployed in high-unemployment areas…

There are some pretty good jobs around, including in parts of Texas and North Dakota. The point is not that these jobs/regions could absorb all of the current unemployed, but rather that we can learn something about the current unemployed (at the margin of course) but noting that these jobs remain unfilled.

First, I would like to know what the unemployment (participation?) rate would be today if American labor had a mobility rate closer to that of the early to mid 1980s.

Second, here is a study (pdf) of a 1976 federal jobs relocation subsidy program. The conclusion is vaguely positive, but not firm. Here is a study (pdf) of relocation assistance in Germany, mostly positive. Here is a good discussion of U.S. trade adjustment relocation assistance with lots of numbers (pdf), it tries to be positive but my reading of the content suggests lukewarm results. Here is a Brookings proposal (pdf).

Some states offer relocation assistance, for Wisconsin you need to have a job elsewhere already lined up. Perhaps that restriction should be eased, but in any case I do not hear of massive success stories from current relocation programs, even if they are net positives. Here is a CRS overview of federal programs for unemployed workers, some of which boost mobility. Here are some FAQs on trade adjustment relocation assistance.

Third, I wonder if a subsidy is the right response here. After all, there is already a potential benefit from moving, assuming the subsidy idea makes sense in the first place. Yet, if we are to accept many of the more pessimistic behavioral accounts of unemployment, a lassitude and feeling of hopelessness sets in. Positive incentives may not suffice, at least not in the absence of a behavioral spur to change the process of decision-making and induce some more pro-active choices.

By the way, there are some bureaucratic complications — not daunting ones but costs nonetheless — if you switch states while looking for a job and collecting UI. Perhaps these paperwork requirements could be eased and turned into a simple one-click process.

What if it turned out that a tax or penalty for unemployed non-movers was overall more effective? Would or should we be willing to support such an idea? Of course it would inevitably fall on some innocent victims as well, people who should not move or people who cannot move, perhaps for reasons of family ties. How about a tax for staying combined with a benefit for leaving?

How about if the tax is based on a Big Data model to limit the number of unjust losers? That would mean more frequent taxes for Appalachian stayers, and less frequent taxes for individuals with elderly dependents on their tax returns.

If the tax were a big net plus for the current unemployed, but hit some innocent losers, and sent the wrong mood affiliation, would we still support it? Should we still support it? What if the tax took the form of poor public services? Does it need to be more aggressive than that?

Should we even be asking these questions?

The labor market effects of immigration and emigration from OECD countries

Here is a new paper by Frédéric Docquier, Çaglar Ozden & Giovanni Peri, forthcoming in Economic Journal:

In this paper, we quantify the labor market effects of migration flows in OECD countries during the 1990’s based on a new global database on the bilateral stock of migrants, by education level. We simulate various outcomes using an aggregate model of labor markets, parameterized by a range of estimates from the literature. We find that immigration had a positive effect on the wages of less educated natives and it increased or left unchanged the average native wages. Emigration, instead, had a negative effect on the wages of less educated native workers and increased inequality within countries.

A gated version of the paper is here, ungated versions are here.

Yes, I am familiar with how these models and estimates work, and yes you can argue back to a “we really can’t tell” point of view, if you are so inclined. But you cannot by any stretch of the imagination argue to some of the negative economic claims about immigration that you will find in the comments section of this blog and elsewhere.

And no I do not favor open borders even though I do favor a big increase in immigration into the United States, both high- and low-skilled. The simplest argument against open borders is the political one. Try to apply the idea to Cyprus, Taiwan, Israel, Switzerland, and Iceland and see how far you get. Big countries will manage the flow better than the small ones but suddenly the burden of proof is shifted to a new question: can we find any countries big enough (or undesirable enough) where truly open immigration might actually work?

In my view the open borders advocates are doing the pro-immigration cause a disservice. The notion of fully open borders scares people, it should scare people, and it rubs against their risk-averse tendencies the wrong way. I am glad the United States had open borders when it did, but today there is too much global mobility and the institutions and infrastructure and social welfare policies of the United States are, unlike in 1910, already too geared toward higher per capita incomes than what truly free immigration would bring. Plunking 500 million or a billion poor individuals in the United States most likely would destroy the goose laying the golden eggs. (The clever will note that this problem is smaller if all wealthy countries move to free immigration at the same time, but of course that is unlikely.)

For the initial pointer I thank Kevin Lewis.

The end of upward mobility?

…two of the nation’s newspapers — The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal — are running extensive multipart series that paint a much darker picture. The U.S., rather than being a land of opportunity, these stories argue, is increasingly a class-bound place of immobility and stratification, where it’s becoming ever harder for the people at the bottom to move up…

Rather than agonizing over relative comparisons, it may be better to concentrate on the simpler and intuitively satisfying concept of absolute "mobility," — whether you are doing better than your parents did, or whether the living standards of a whole group of people are rising over time. From this perspective, there are signs that this past decade has had more upward mobility compared with the previous two decades…

There’s yet another big problem: we actually know very little about whether relative mobility increased or decreased during the New Economy decade because complete data don’t exist yet. With a few exceptions, most studies stop with the mid- or late 1990s.

Here’s what we do know: Over the past decade, virtually every traditionally disadvantaged group made gains in absolute terms. Take, for example, families headed by immigrants who entered the country in the 1980s. The poverty rate for such families dropped sharply, from 26.6% in 1995 to 16.4% in 2003…Similarly, a combination of welfare reform and tight labor markets helped drive down the poverty rate for female-headed households with children from 46.1% in 1993 to 35.5% in 2003….it beats the total lack of progress in the previous decade.

That is from 20 June 2005, Business Week, by Michael Mandel. Here is a new book on who gets ahead in low-wage labor markets. Here is my previous post on Horatio Alger. Here is my previous post on the family as a source of inequality.

Does the case for free trade require factor immobility?

Paul Craig Roberts has been claiming that the traditional case for free trade requires immobile factors of production. Michael Kinsley offers his [critical] understanding of the argument as well. I take the bottom line to be as follows. If labor can migrate, trade will not always benefit both countries, in all conceivable circumstances. Those laborers will move to the country with the strongest absolute advantage. This may lead to a brain drain at home, and perhaps crowding and lower wages in the recipient country. In other words, there are potential externalities from the migration of labor.

Another scenario is that American capital flows, say, to China, instead of Chinese labor coming to America. America will not experience overcrowding, nor will China have a brain drain. Still the real wages of some American workers might fall. Chinese labor will be concentrated in some sectors more than others. Certainly some American workers will be worse off, though economists will continue to insist that wealth as a whole will go up.

None of these arguments are new and they do not represent a novel critique of free trade. The first version of the argument suggests, at best, that we cannot currently move to complete free immigration. It does not dent the case for free trade. The second argument simply points out that wealth-improving policies do not benefit everyone.

The ever-insightful Daniel Drezner offers some further commentary on the new anti-free trade arguments. He also notes that the “factor mobility” scenario does not involve fundamentally new considerations from the “factor immobility” scenario.

The bottom line: We should take care to minimize the negative externalities from foreign trade and investment, and this is best done by well-functioning labor markets and sound macroeconomic policy. Basically Roberts is peddling snake oil. His argument boils down to old-style protectionism, dressed up in new rhetorical garb, not new substance.

By the way, as an economist, I sometimes receive irate emails telling me I have never had to compete with subsidized foreign workers. It is then suggested that if I faced such competition, I would not favor free trade. This description of the facts is not true. Most of my Ph.d. class at Harvard came from other countries, and many of them were heavily subsidized by their governments. I was not subsidized by the American government and yet I had to compete with these people for jobs.

Addendum: See further remarks by Joseph Salerno. See also Truck&Barter., which offers further links of value.