Results for “michael kremer” 61 found

My Conversation with Michael Kremer

Self-recommending, here is the transcript, audio, and video. Here is part of the summary:

Michael joined Tyler to discuss the intellectual challenge of founding organizations, applying methods from behavioral economics to design better programs, how advanced market commitments could lower pharmaceutical costs for consumers while still incentivizing R&D, the ongoing cycle of experimentation every innovator understands, the political economy of public health initiatives, the importance of designing institutions to increase technological change, the production function of new technologies, incentivizing educational achievement, The Odyssey as a tale of comparative development, why he recently transitioned to University of Chicago, what researchers can learn from venture capitalists, his current work addressing COVID-19, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: I’ve seen estimates — they’re actually from one of the groups you founded — that a deworming pill could cost as little as 50 cents a year per person in many parts of Africa. So why isn’t deworming done much more?

KREMER: You could say the glass is half empty, you can say it’s half full, or you can say it’s almost three-quarters full. I think it’s about three-quarters full. When I first got involved in deworming, it was testing a small NGO program. We found phenomenal effects of that. The original work found health gains and education gains. Now we’ve tracked people over 20 years, and we’re seeing people have a better standard of living or earning more.

Following the early results, we presented the results of the government of Kenya to the World Bank. Kenya scaled this up nationally, in part with assistance from the World Bank, primarily just in conveying some of that information.

Indian states started doing that, and then the national government of India took this on. They’re reaching — a little bit harder to know the exact numbers — but probably 150 million people a year. Many other countries are doing this as well, so it’s actually quite widely adopted.

COWEN: But there’s still a massive residual, right?

KREMER: That is for sure.

COWEN: What’s your best explanatory theory of why the residual isn’t smaller? It would seem to be a vote winner. African countries, fiscally, are in much better shape than they used to be. They’re more democratic. Public health looks much better. The response to COVID-19 has probably been better than many people expected, say, in Senegal, possibly in Kenya. So why not do deworming more?

KREMER: The people who have worms are pretty poor people. The richer people are less likely to have worms within a given society. Richer people are probably more politically influential.

There’s also something about worms — they gradually build up in your body, and one worm is not going to do that much damage. The problem is when you’ve got lots of worms in your body, and even there, it’s going to take time.

I’ve had malaria. I don’t think I’ve had worms. I hope I haven’t. When you have malaria, you feel terrible. You go from feeling fine to feeling terrible, and then you take the medicine. You feel great afterwards. With worms, it’s much more like a chronic thing, and when you expel the worms from your body, that’s sort of gross. I don’t think, even at the individual level, do you have quite the demand that would be commensurate with the scale of the problem. That’s a behavioral economics explanation.

I think there are political issues and then there are behavioral issues. I would actually say that a huge, huge issue . . . This sounds very boring, but this falls between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education, and each one of them has different priorities. The Ministry of Health is going to be worried about delivering things through clinics. They’re worried about HIV and malaria, tuberculosis, as it should be.

The Ministry of Education — they’re worried about teacher strikes. It’s very easy for something to either fall between the cracks or be the victim of turf wars. It sounds too small to be, “How can that really get in the way?” But anybody who’s spent time working in governments understands those things can very easily get in the way. In some ways, it’s surprising how much progress has been made.

Here’s one way the political economy works in favor. You mentioned democracy — I think that’s a factor. I actually find — and I don’t want to be necessarily a big fan of politicians — but in some ways, politicians hear how much this costs, and they think they can affect that many people for that small amount of money, and they’re like, “Hey, I want to get on that. Maybe this is something I can claim as an achievement.” We saw that in Kenya. We saw that in India.

And:

COWEN: Let’s say the current Michael Kremer sets up another high school in Kenya. What is it that you would do that the current high schools in Kenya are not doing? What would you change? You’re in charge.

KREMER: Right. We’ve learned a lot in education research in recent years. One thing that we saw in Kenya, but was also seen in India and many other places, is that it’s very easy for kids to fall behind the curriculum. Curricula, in particular in developing countries, tend to be set at a fairly high level, similar to what you would see in developed countries.

However, kids are facing all sorts of disadvantages, and there are all sorts of problems in the way the system works. There’s often high teacher absence. Kids are sick. Kids don’t have the preparation at home, often. So kids can fall behind the curriculum.

Whereas we’ve had the slogan in the US, “No Child Left Behind,” in developing countries, education system is focused on kids at the top of the distribution. What’s been found is, if you can set up — and there are a whole variety of different ways to do this — either remedial education systems or some technology-aided systems that are adaptive, that go to where the kid is . . . I’ve seen huge gains from this in India, and we’re starting to see adoption of this in Africa as well, and that can have a very big impact at quite low cost.

Intelligent throughout.

What should I ask Michael Kremer?

I will be having a Conversation with him soon. So what should I ask him?

Here are previous MR posts on Michael Kremer.

Michael Kremer, Nobel laureate

To Alex’s excellent treatment I will add a short discussion of Kremer’s work on deworming (with co-authors, most of all Edward Miguel), here is one summary treatment:

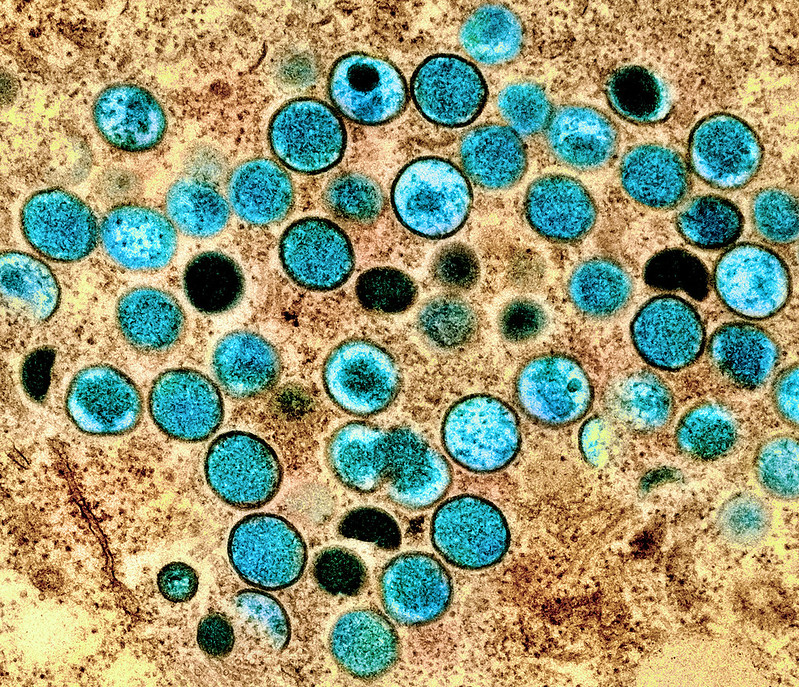

Intestinal helminths—including hookworm, roundworm, whipworm, and schistosomiasis—infect more than one-quarter of the world’s population. Studies in which medical treatment is randomized at the individual level potentially doubly underestimate the benefits of treatment, missing externality benefits to the comparison group from reduced disease transmission, and therefore also underestimating benefits for the treatment group. We evaluate a Kenyan project in which school-based mass treatment with deworming drugs was randomly phased into schools, rather than to individuals, allowing estimation of overall program effects. The program reduced school absenteeism in treatment schools by one-quarter, and was far cheaper than alternative ways of boosting school participation. Deworming substantially improved health and school participation among untreated children in both treatment schools and neighboring schools, and these externalities are large enough to justify fully subsidizing treatment. Yet we do not find evidence that deworming improved academic test scores.

If you do not today have a worm, there is some chance you have Michael Kremer to thank!

With Blanchard, Kremer also has an excellent and these days somewhat neglected piece on central planning and complexity:

Under central planning, many firms relied on a single supplier for critical inputs. Transition has led to decentralized bargaining between suppliers and buyers. Under incomplete contracts or asymmetric information, bargaining may inefficiently break down, and if chains of production link many specialized producers, output will decline sharply. Mechanisms that mitigate these problems in the West, such as reputation, can only play a limited role in transition. The empirical evidence suggests that output has fallen farthest for the goods with the most complex production process, and that disorganization has been more important in the former Soviet Union than in Central Europe.

Kremer with co-authors also did excellent work on the benefits of school vouchers in Colombia. And here is Kremer’s work on teacher incentives — incentives matter! His early piece on wage inequality with Maskin, from 1996, was way ahead of its time. And don’t forget his piece on peer effects and alcohol use: many college students think the others are drinking more than in fact they are, and publicizing the lower actual level of drinking can diminish alcohol abuse problems. The Hajj has an impact on the views of its participants, and “… these results suggest that students become more empathetic with the social groups to which their roommates belong,.” link here.

And don’t forget his famous paper titled “Elephants.” Under some assumptions, the government should buy up a large stock of ivory tusks, and dump them on the market strategically, to ruin the returns of elephant speculators at just the right time. No one has ever worked through the issue before of how to stop speculation in such forbidden and undesirable commodities.

Michael Kremer has produced a truly amazing set of papers.

Implementing Michael Kremer’s vaccines idea

…finance ministers from at least three Western countries are scheduled to meet in Rome next week to announce a pilot program for delivering next-generation vaccines more rapidly to poor nations. An official for the GAVI Alliance, an international vaccines group, confirmed that the project would be the first step of a controversial plan to pay qualifying vaccine makers a higher price than they would ordinarily receive for their products in impoverished areas hard hit by infectious diseases.

Here is the full story. Here is Alex on Kremer’s idea.

The Nobel Prize in Economic Science Goes to Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer

The Nobel Prize goes to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer (links to home pages) for field experiments in development economics. Esther Duflo was a John Bates Clark Medal winner, a MacArthur “genius” award winner, and is now the second woman to win the economics Nobel and by far the youngest person to ever win the economics Nobel (Arrow was the previous youngest winner!). Duflo and Banerjee are married so these are also the first spouses to win the economics Nobel although not the first spouses to win Nobel prizes–there was even one member of a Nobel prize winning spouse-couple who won the Nobel prize in economics. Can you name the spouses?

Michael Kremer wrote two of my favorite papers ever. The first is Patent Buyouts which you can find in my book Entrepreneurial Economics: Bright Ideas from the Dismal Science. The idea of a patent buyout is for the government to buy a patent and rip it up, opening the idea to the public domain. How much should the government pay? To decide this they can hold an auction. Anyone can bid in the auction but the winner receives the patent only say 10% of the time–the other 90% of the time the patent is bought by the government at the market price. The value of this procedure is that 90% of the time we get all the incentive properties of the patent without any of the monopoly costs. Thus, we eliminate the innovation tradeoff. Indeed, the government can even top the market price up by say 15% in order to increase the incentive to innovate. You might think the patent buyout idea is unrealistic. But in fact, Kremer went on to pioneer an important version of the idea, the Advance Market Commitment for Vaccines which was used to guarantee a market for the pneumococcal vaccine which has now been given to some 143 million children. Bill Gates was involved with governments in supporting the project.

My second Kremer paper is Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990. An economist examining one million years of the economy! I like to say that there are two views of humanity, people are stomachs or people are brains. In the people are stomachs view, more people means more eaters, more takers, less for everyone else. In the people are brains view, more people means more brains, more ideas, more for everyone else. The people are brains view is my view and Paul Romer’s view (ideas are nonrivalrous). Kremer tests the two views. He shows that over the long run economic growth increased with population growth. People are brains.

Oh, and can I add a third Kremer paper? The O-Ring Model of Development is a great and deep paper. (MRU video on the O-ring model).

The work for which the Nobel was given is for field experiments in development economics. Kremer began this area of research with randomized trials of educational policies in Kenya. Duflo and Banerjee then deepened and broadened the use of field experiments and in 2003 established the Poverty Action Lab which has been the nexus for field experiments in development economics carried on by hundreds of researchers around the world.

Much has been learned in field experiments about what does and also doesn’t work. In Incentives Work, Dufflo, Hanna and Ryan created a successful program to monitor and reduce teacher absenteeism in India, a problem that Michael Kremer had shown in Missing in Action was very serious with some 30% of teachers not showing up on a typical day. But when they tried to institute a similar program for nurses in Putting a Band-Aid on A Corpse the program was soon undermined by local politicians and “Eighteen months after its inception, the program had become completely ineffective.” Similarly, Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster and Kinnan find that Microfinance is ok but no miracle (sorry fellow laureate Muhammad Yunus). A frustrating lesson has been the context dependent nature of results and the difficult of finding external validity. (Lant Pritchett in a critique of the “randomistas” argues that real development is based on macro-policy rather than micro-experiment. See also Bill Easterly on the success of the Washington Consensus.)

Duflo, Kremer and Robinson study How High Are Rates of Return to Fertilizer? Evidence from Field Experiments in Kenya. This is an especially interest piece of research because they find that rates of return are very high but that farmers don’t use much fertilizer. Why not? The reasons seem to have much more to do with behavioral biases than rationality. Some interventions help:

Our findings suggest that simple interventions that affect neither the cost of, nor the payoff to, fertilizer can substantially increase fertilizer use. In particular, offering farmers the option to buy fertilizer (at the full market price, but with free delivery) immediately after the harvest leads to an increase of at least 33 percent in the proportion of farmers using fertilizer, an effect comparable to that of a 50 percent reduction in the price of fertilizer (in contrast, there is no impact on fertilizer adoption of offering free delivery at the time fertilizer is actually needed for top dressing). This finding seems inconsistent with the idea that low adoption is due to low returns or credit constraints, and suggests there may be a role for non–fully rational behavior in explaining production decisions.

This is reminiscent of people in developed countries who don’t adjust their retirement savings rates to take advantage of employer matches. (A connection to Thaler’s work).

Duflo and Banerjee have conducted many of their field experiments in India and have looked at not just conventional questions of development economics but also at politics. In 1993, India introduced a constitutional rule that said that each state had to reserve a third of all positions as chair of village councils for women. In a series of papers, Duflo studies this natural experiment which involved randomization of villages with women chairs. In Women as Policy Makers (with Chattopadhyay) she finds that female politicians change the allocation of resources towards infrastructure of relevance to women. In Powerful Women (Beaman et al.) she finds that having once had a female village leader increases the prospects of future female leaders, i.e. exposure reduces bias.

Before Banerjee became a randomistas he was a theorist. His A Simple Model of Herd Behavior is also a favorite. The essence of the model can be explained in a simple example (from the paper). Suppose there are two restaurants A and B. The prior probability is that A is slightly more likely to be a better restaurant than B but in fact B is the better restaurant. People arrive at the restaurants in sequence and as they do they get a signal of which restaurant is better and they also see what choice the person in front of them made. Suppose the first person in line gets a signal that the better restaurant is A (contrary to fact). They choose A. The second person then gets a signal that the better restaurant is B. The second person in line also sees that the first person chose A, so they now know one signal is for A and one is for B and the prior is A so the weight of the evidence is for A—the second person also chooses restaurant A. The next person in line also gets the B signal but for the same reasons they also choose A. In fact, everyone chooses A even if 99 out of 100 signals are B. We get a herd. The sequential information structure means that the information is wasted. Thus, how information is distributed can make a huge difference to what happens. A lot of lessons here for tweeting and Facebook!

Banerjee is also the author of some original and key pieces on Indian economic history, most notably History, Institutions, and Economic Performance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India (with Iyer).

Duflo’s TED Talk. Previous Duflo posts; Kremer posts; Banerjee posts on MR.

Before last year’s Nobel announcement Tyler wrote:

I’ve never once gotten it right, at least not for exact timing, so my apologies to anyone I pick (sorry Bill Baumol!). Nonetheless this year I am in for Esther Duflo and Abihijit Banerjee, possibly with Michael Kremer, for randomized control trials in development economics.

As Tyler predicted he was wrong and also right. Thus, this years win is well-timed and well-deserved. Congratulations to all.

Michael Clemens on the Millennium Village project

It's hard to summarize, so read the whole thing. But he is calling for a closer look at the evidence and the application of RCT [randomized control trial] standards. Here is an excerpt:

First, the fact that a technology has been scientifically proven in isolation–such as a certain fertilizer proven to raise crop yields–does not mean that it will improve people’s well-being amidst the complexities of real villages. Recent research by Esther Duflo, CGD non-resident fellow Michael Kremer, and Jonathan Robinson shows that fertilizer use is scientifically proven highly effective at raising farm yields and farmers’ profits in Kenya. But for complex reasons very few farmers wish to adopt fertilizer, even those well trained in its use and usefulness. This means that this proven technology has enormous difficulty raising farmers’ incomes in practice. The gap between agronomy and development is very hard to cross.

Second, it is not sufficient to compare treated villages to untreated villages that were chosen ex-post as comparison villages because they appear similar. Many recent research papers have shown this conclusively. A long list of studies conducted over decades showed that African and other children learned much more in schools that had textbooks than in schools that appeared otherwise similar but did not have textbooks. Paul Glewwe, Michael Kremer, and Sylvie Moulin evaluated a large intervention in some of the neediest schools in Kenya (ungated version here, published here). Schools that received textbooks were randomly chosen from an initial pool of candidates. The problem: Children did not learn more in the treated schools than in the untreated schools.

Chris Blattman comments.

Kremer’s Prize

The Advance Market Commitment for vaccines launched on friday. Under the commitment a group of developed nations (Canada, Italy, Norway, Russia, the United Kingdom) and Bill Gates! (The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) promises to pay for a pneumococcal vaccine suitable in price and effectiveness for the developing world. The idea, the brain child of economist Michael Kremer, could save millions of lives over the next several decades. Kremer deserves a Prize for his Prize – in Peace or Economics.

Owen, who played a part in the project, has more background and musings.

Elephant tusks, incentives, and the sacred

In a heap of burnt and powdered elephant tusks, you can see so much of social science.

If you visit Nairobi National Park, you will see rhinos, hippos, and giraffes, all within sight of the city skyline. You also will see an organized site showing several large mounds of burnt and powdered elephant tusks. They are a tribute to the elephant, and along with the accompanying signs, a condemnation of elephant poaching.

Starting in 1989, the government had confiscated a large number of tusks from the poachers, and as part of their anti-poaching campaign they burnt those tusks and placed the burnt ashes on display in the form of mounds. There are also several signs telling visitors that it is forbidden to take the ashes from the site. There have since been subsequent organized tusk burns.

In essence, the government is trying to communicate the notion that the elephant tusks are sacred, and should not be regarded as material for either commerce or poaching or for that matter souvenir collecting. “We will even destroy this, rather than let you trade it.” In economic terminology, you could say the government is trying to shift the supply and demand curves by changing norms in the longer run.

The economist of course is tempted to look beneath the surface of such a policy. If the government destroys a large number of elephant tusks, the price of tusks on the black market might go up. The higher tusk price could in turn motivate yet more poaching and tusk trading, thus countermanding the original intent of the policy.

This scenario, whether the most relevant equilibrium or not, is not just fantasy. Economics Nobel Laureate Michael Kremer (with co-author Charles Morcom) has a well-known paper simply called “Elephants.” In that research, symbolic goods and the sacred are put aside and they take an “incentives only” approach to elephant tusk policy. The abstract runs like this:

Many open-access resources, such as elephants, are used to produce storable goods. Anticipated future scarcity of these resources will increase current prices and poaching. This implies that, for given initial conditions, there may be rational expectations equilibria leading to both extinction and survival. The cheapest way for governments to eliminate extinction equilibria may be to commit to tough antipoaching measures if the population falls below a threshold. For governments without credibility, the cheapest way to eliminate extinction equilibria may be to accumulate a sufficient stockpile of the storable good and threaten to sell it should the population fall.

The key sentence there, for our purposes, is that the government might end up selling its stock of tusks on the open market, to deter speculators. And thus, in that scenario, you do not want to be burning the tusks.

The Kremer and Morcom policy analysis (is it a recommendation? I am not sure) would of course involve the non-credible government in the market for elephant tusks. Periodically wiping out the speculators would have its benefits, for the economic reasons outlined in their paper. At the same time, a government playing around in that market would have a much harder time making the case that elephants and elephant tusks are something sacred. Such a government would have a much harder time making the case that the tusks never should be traded.

Which is better? The policy conducted by the Kenyan government, or the policy described in Kremer and Morcom?

From this distance, I do not pretend to know. I can also see that an anti-poaching government may not have credibility now, but it may wish to invest in “the sacred” for a pending future where its credibility is greater. Treating elephants and elephant tusks as sacred, even if counterproductive in some short runs, may contribute to establishing the credibility of said government. And indeed part of the credibility of today’s Kenyan government (while decidedly mixed) comes from its ability to keep many of the nature reserves up and running in good order. Many of the animals are coming back, and tourism continues to increase.

Many non-economists think only in terms of the sacred and the symbolic goods in human society. They ignore incentives. Furthermore, our politics and religious sects encourage such modes of evaluation.

Many economists think only in terms of incentives, and they do not have a good sense of how to integrate symbolic goods into their analysis. They often come up with policy proposals that either offend people or simply fall flat.

Wisdom in balancing these two perspectives is often at the heart of good social science, and not just for elephant tusks. And who exactly is an expert in that?

Identify a Market Failure and Win Prizes!

The University of Chicago’s Market Shaping Accelerator, led by Rachel Glennerster, Michael Kremer, and Chris Snyder (Dartmouth), is offering up to two million dollars in prizes for new pull mechanisms and applications.

Our inaugural MSA Innovation Challenge 2023 will award up to $2,000,000 in total prizes for ideas that identify areas where a pull mechanism would help spur innovation in biosecurity, pandemic preparedness, and climate change, and for teams to design that incentive mechanism from ideation to contract signing.

Participating teams will have access to the world’s leading experts in market shaping and technical support from domain specialists to compete for their part of up to $2 million prize during multiple phases. Top ideas will also gain the MSA’s support in fundraising for the multi-millions or billions of dollars needed to back their pull mechanism.

…Pull mechanisms are policy tools that create incentives for private sector entities to invest in research and development (R&D) and bring solutions to market. Whereas “push” funding pays for inputs (e.g. research grants), “pull” funding pays for outputs and outcomes (i.e. prizes and milestone contracts). These mechanisms “pull” innovation by creating a demand for a specific product or service, which drives private sector investment and efforts towards developing and delivering that product or technological solution.

One example of a pull mechanism is an Advance Market Commitment (AMC), which is a type of contract where a buyer, such as a government or philanthropic organization, commits to purchasing (or subsidizing) a product or service at a certain price and quantity once it becomes available. This commitment creates a market for the product or service, providing a financial incentive for innovators to invest in R&D and develop solutions to meet that demand.

The first round of prizes are $4,000 for an idea!

The submission template asks applicants to identify a market failure where the social value exceeds private incentives and where we know the measurable outcome we want to encourage (e.g. the development of a vaccine, capturing carbon out of the air, etc.). Submissions are accepted from individuals 18 years and older and organizations around the globe whose participation and receipt of funding will not violate applicable law.

See here for more.

Monday assorted links

1. Bodhana Sivanandan, seven, shines at British Championships. And 17-year-old Pragnanandhaa defeats Carlsen in their Rapid match yesterday, and takes #2 in the FTX tourney.

4. Colombia might decriminalize cocaine.

5. In this galaxy cluster, you can hear a black hole. Sounds like it does in the movies!

Dose Stretching for the Monkeypox Vaccine

We are making all the same errors with monkeypox policy that we made with Covid but we are correcting the errors more rapidly. (It remains to be seen whether we are correcting rapidly enough.) I’ve already mentioned the rapid movement of some organizations to first doses first for the monkeypox vaccine. Another example is dose stretching. I argued on the basis of immunological evidence that A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca and with Witold Wiecek, Michael Kremer, Chris Snyder and others wrote a paper simulating the effect of dose stretching for COVID in an SIER model. We even worked with a number of groups to accelerate clinical trials on dose stretching. Yet, the idea was slow to take off. On the other hand, the NIH has already announced a dose stretching trial for monkeypox.

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are getting ready to explore a possible work-around. They are putting the finishing touches on the design of a clinical trial to assess two methods of stretching available doses of Jynneos, the only vaccine in the United States approved for vaccination against monkeypox.

They plan to test whether fractional dosing — using one-fifth of the regular amount of vaccine per person — would provide as much protection as the current regimen of two full doses of the vaccine given 28 days apart. They will also test whether using a single dose might be enough to protect against infection.

The first approach would allow roughly five times as many people to be vaccinated as the current licensed approach, and the latter would mean twice as many people could be vaccinated with existing vaccine supplies.

…The answers the study will generate, hopefully by late November or early December, could significantly aid efforts to bring this unprecedented monkeypox outbreak under control.

Another interesting aspect of the dose stretching protocol is that the vaccine will be applied to the skin, i.e. intradermally, which is known to often create a stronger immune response. Again, the idea isn’t new, I mentioned it in passing a couple of times on MR. But we just weren’t prepared to take these step for COVID. Nevertheless, COVID got these ideas into the public square and now that the pump has been primed we appear to be moving more rapidly on monkeypox.

Addendum: Jonathan Nankivell asked on the prediction market, Manifold Markets, ‘whether a 1/5 dose of the monkey pox vaccine would provide at least 50% the protection of the full dose?’ which is now running at a 67% chance. Well worth doing the clinical trial! Especially if we think that the supply of the vaccine will not expand soon.

Direct Instruction Produces Large Gains in Learning, Kenya Edition

In an important new paper, Can Education be Standardized? Evidence from Kenya, Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Anthony Keats, Michael Kremer, Isaac Mbiti and Owen Ozier evaluate Bridge International schools using a large randomized experiment. Twenty five thousand Kenyan students applied for 10,000 scholarships to Bridge International and the scholarships were given out by lottery.

Kenyan pupils who won a lottery for two-year scholarships to attend schools employing a highly-structured and standardized approach to pedagogy and school management learned more than students who applied for, but did not win, scholarships.

After being enrolled at these schools for two years, primary-school pupils gained approximately the equivalent of 0.89 extra years of schooling (0.81 standard deviations), while in pre-primary grades, pupils gained the equivalent of 1.48 additional years of schooling (1.35 standard deviations).

These are very large gains. Put simply, children in the Bridge programs learnt approximately three years worth of material in just two years! Now, I know what you are thinking. We have all seen examples of high-quality, expensive educational interventions that don’t scale–that was the point of my post Heroes are Not Replicable and see also my recent discussion of the Perry Preschool project–but it’s important to understand the backstory of the Bridge study. Bridge Academy uses Direct Instruction and Direct Instruction scales! We know this from hundreds of studies. In 2018 I wrote (no indent):

These are very large gains. Put simply, children in the Bridge programs learnt approximately three years worth of material in just two years! Now, I know what you are thinking. We have all seen examples of high-quality, expensive educational interventions that don’t scale–that was the point of my post Heroes are Not Replicable and see also my recent discussion of the Perry Preschool project–but it’s important to understand the backstory of the Bridge study. Bridge Academy uses Direct Instruction and Direct Instruction scales! We know this from hundreds of studies. In 2018 I wrote (no indent):

What if I told you that there is a method of education which significantly raises achievement, has been shown to work for students of a wide range of abilities, races, and socio-economic levels and has been shown to be superior to other methods of instruction in hundreds of tests?….I am reminded of this by the just-published, The Effectiveness of Direct Instruction Curricula: A Meta-Analysis of a Half Century of Research which, based on an analysis of 328 studies using 413 study designs examining outcomes in reading, math, language, other academic subjects, and affective measures (such as self-esteem), concludes:

…Our results support earlier reviews of the DI effectiveness literature. The estimated effects were consistently positive. Most estimates would be considered medium to large using the criteria generally used in the psychological literature and substantially larger than the criterion of .25 typically used in education research (Tallmadge, 1977). Using the criteria recently suggested by Lipsey et al. (2012), 6 of the 10 baseline estimates and 8 of the 10 adjusted estimates in the reduced models would be considered huge. All but one of the remaining six estimates would be considered large. Only 1 of the 20 estimates, although positive, might be seen as educationally insignificant.

…The strong positive results were similar across the 50 years of data; in articles, dissertations, and gray literature; across different types of research designs, assessments, outcome measures, and methods of calculating effects; across different types of samples and locales, student poverty status, race-ethnicity, at-risk status, and grade; across subjects and programs; after the intervention ceased; with researchers or teachers delivering the intervention; with experimental or usual comparison programs; and when other analytic methods, a broader sample, or other control variables were used.

Indeed, in 2015 I pointed to Bridge International as an important, large, and growing set of schools that use Direct Instruction to create low-cost, high quality private schools in the developing world. The Bridge schools, which have been backed by Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates, have been controversial which is one reason the Kenyan results are important.

One source of controversy is that Bridge teachers have less formal education and training than public school teachers. But Brdige teachers need less formal education because they are following a script and are closely monitored. DI isn’t designed for heroes, it’s designed for ordinary mortals motivated by ordinary incentives.

School heads are trained to observe teachers twice daily, recording information on adherence to the detailed teaching plans and interaction with pupils. School heads are given their own detailed scripts for teacher observation, including guidance for preparing for the observation, what teacher behaviors to watch for while observing, and how to provide feedback. School heads are instructed to additionally conduct a 15 minute follow up on the same day to check whether teachers incorporated the feedback and enter their scores through a digital system. The presence of the scripts thus transforms and simplifies the task of classroom observation and provision of feedback to teachers. Bridge also standardizes a range of other processes from school construction to financial management.

Teachers are observed twice daily! The model is thus education as a factory with extensive quality control–which is why teachers don’t like DI–but standardization, scale, and factory production make civilization possible. How many bespoke products do you buy? The idea that education should be bespoke gets things entirely backward because that means that you can’t apply what you learn about what works at scale–Heroes are Not Replicable–and thus you don’t get the benefits of refinement, evolution, and continuous improvement that the factory model provides. I quoted Ian Ayres in 2007:

“The education establishment is wedded to its pet theories regardless of what the evidence says.” As a result they have fought it tooth and nail so that “Direct Instruction, the oldest and most validated program, has captured only a little more than 1 percent of the grade-school market.”

Direct Instruction is evidence-based instruction that is formalized, codified, and implemented at scale. There is a big opportunity in the developing world to apply the lessons of Direct Instruction and accelerate achievement. Many schools in the developed world would also be improved by DI methods.

Addendum 1: The research brief to the paper, from which I have quoted, is a short but very good introduction to the results of the paper and also to Direct Instruction more generally.

Addendum 2: A surprising number of people over the years have thanked me for recommending DI co-founder Siegfried Engelmann’s Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons.

Can Education be Standardized? Evidence from Kenya

From Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Anthony Keats, Michael Kremer, Isaac Mbiti, and Owen Ozier:

We examine the impact of enrolling in schools that employ a highly-standardized approach to education, using random variation from a large nationwide scholarship program. Bridge International Academies not only delivers highly detailed lesson guides to teachers using tablet computers, it also standardizes systems for daily teacher monitoring and feedback, school construction, and financial management. At the time of the study, Bridge operated over 400 private schools serving more than 100,000 pupils. It hired teachers with less formal education and experience than public school teachers, paid them less, and had more working hours per week. Enrolling at Bridge for two years increased test scores by 0.89 additional equivalent years of schooling (EYS) for primary school pupils and by 1.48 EYS for pre-primary pupils. These effects are in the 99th percentile of effects found for at-scale programs studied in a recent survey. Enrolling at Bridge reduced both dispersion in test scores and grade repetition. Test score results do not seem to be driven by rote memorization or by income effects of the scholarship.

Promising results, to be sure…

Fractional Dosing Trials

My paper Testing fractional doses of COVID-19 Vaccines, co-authored with Kremer et al., has now been published at PNAS. I covered the paper in A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective than A Full Dose of Astra Zeneca and other posts so I won’t belabor the basic ideas. One new point is that thanks to the indefatigable Michael Kremer and the brilliant Witold Wiecek, clinical trials on fractional dosing on a large scale have begun in Nigeria. Here are a few key points:

WHO SAGE Outreach: The authors have met and presented their work to the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), with follow-up meetings to present evidence coming from new studies.

DIL Workshop and Updates: In the fall of 2021, the Development Innovation Lab (DIL) at UChicago, led by Professor Kremer, hosted a workshop on fractional dosing, collecting updates from clinical researchers from multiple countries conducting fractional dosing trials for COVID-19 vaccines. The workshop also covered issues relating to trial design and included participants from Belgium, Brazil, Ghana, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Thailand, South Africa, UK and the US.

CEPI Outreach: Professor Kremer has also presented this research to The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which is now pursuing a platform trial of fractional dosing.

Country Trials – Nigeria: With the support of DIL and the research team and generous support and advice from WAM Foundation, the charitable arm of Weiss Asset Management and Open Philanthropy, a trial is being conducted in Nigeria by the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Research and Development, National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, and the National Primary Health Care Development Agency, in coordination with the Federal Ministry of Health.

A comprehensive list of all the trials on fractional dosing conducted to date is at the link. Fractional dosing may come too late for COVID-19 vaccines but perhaps next time a shortage of a vaccine looms we will be more quick to consider policies to stretch supplies.

Operation Warp Speed: A Story Yet to be Told

Operation Warp Speed was by far the most successful government program against COVID. But as of yet there is very little discussion or history of the program. As just an indication I looked for references in a bunch of pandemic books to General Perna who co-led OWS with Moncef Slaoui. Michael Lewis in The Premonition never mentions Perna. Neither does Slavitt in Preventable. Nor does Wright in The Plague Year. Nor does Gottlieb in Uncontrolled Spread. Abutaleb and Paletta in Nightmare Scenario have just two index entries for Perna basically just stating his appointment and meeting with Trump.

Yet there are many questions to be asked about OWS. Who wrote the contracts? Who chose the vaccines? Who found the money? Who ran the day to day operation? Why was the state and local rollout so slow and uneven? How was the DPA used? Who lifted the regulations? How was the FDA convinced to go fast?

I don’t know the answer to these questions. I suspect when it is all written down, Richard Danzig will be seen as an important behind the scenes player in the early stages (I was involved with some meetings with him as part of the Kremer team). Grogan at the DPC seems under-recognized. Peter Marks at the FDA was likely extremely important in getting the FDA to run with the program. Marks brought people like Janet Woodcock from the FDA to OWS so you had a nominally independent group but one completely familiar with FDA policy and staff and that was probably critical. And of course Slaoui and Perna were important leaders and communicators with the private sector and the logistics group but they have yet to be seriously debriefed.

It’s also time for a revisionist account of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors. Michael Kremer and I spoke to the DPC and the CEA early on in the pandemic and argued for a program similar to what would later be called OWS. The CEA, however, was way ahead of the game. In Sept of 2019 (yes, 2019!) the CEA produced a report titled Mitigating the Impact of Pandemic Influenza through Vaccine Innovation. The report calculates the immense potential cost of a pandemic and how a private-public partnership could mitigate these costs–all of this before anyone had heard the term COVID. Nor did that happen by accident. Thomas Philipson, the CEA chair, had made his reputation in the field of economic epidemiology, incorporating incentives and behavioral analysis in epidemiological models to understand HIV and the spread of other infectious diseases. Eric Sun, another CEA economist, had also written with Philipson about the FDA and its problems. Casey Mulligan was another CEA chief economist who understand the danger of pandemics and was influenced by Sam Peltzman on the costs of FDA delay. So the CEA was well prepared for the pandemic and I suspect they gave Trump very good advice on starting Operation Warp Speed.

In short, someone deserves credit for a multi-trillion-dollar saving government program! More importantly, we know a lot about CDC and FDA failure but in order to know what we should build upon we also need to know what worked. OWS worked. We need a history of how and why.