Results for “more police” 437 found

More Police, Fewer Prisons, Less Crime

The New York times as a good piece on prisons, police and crime:

“The United States today is the only country I know of that spends more on prisons than police,” said Lawrence W. Sherman, an American criminologist on the faculties of the University of Maryland and Cambridge University in Britain. “In England and Wales, the spending on police is twice as high as on corrections. In Australia it’s more than three times higher. In Japan it’s seven times higher. Only in the United States is it lower, and only in our recent history.”

…Dr. Ludwig and Philip J. Cook, a Duke University economist, calculate that nationwide, money diverted from prison to policing would buy at least four times as much reduction in crime. They suggest shrinking the prison population by a quarter and using the savings to hire another 100,000 police officers.

My work on policing in Washington, DC (with Jon Klick) also strongly suggests that more police pass the cost benefit test; we suggest that doubling the police force would not be unreasonable.

More Police, Less Crime

After more than two weeks of unusual killings and robberies in Washington DC, Police Chief Charles H. Ramsey has called a crime emergency. During a crime emergency the Chief can increase shifts and get more police on the street. This is exactly the right thing to do. My research with Jon Klick shows that crime in Washington DC falls significantly during high terror-alert periods when the police double up on shifts much as they do during a crime emergency.

More generally, when one combines estimates of police effectiveness that come from myself and Klick, Steve Levitt, Bill Evans and Emily Owens and others with data on the costs of hiring police, it’s clear that police are a bargain. We could double the number of police in the United States and the costs of crime would fall by substantially more than the cost of police. (Reallocating police and prison space from drug users to violent criminals would also help.)

Why don’t NYPD police officers wear more masks?

While police officers may forgo mask-wearing for any number of reasons, from peer pressure within ranks that are loath to change to a desire to more easily communicate, the images have fueled a perception of the police as arrogant and dismissive of protesters’ health — perhaps even at the peril of their own.

And while several officers have conspicuously knelt down with or hugged people at rallies, the widespread failure to use masks is creating a more standoffish look, one that protesters say suggests that the police operate above the rules — one of the very beliefs motivating the nationwide movement.

“If you’re out here to protect the public, it starts with you,” said Chaka McKell, 46, a carpenter from Bedford-Stuyvesant who attended a protest in Downtown Brooklyn on Monday. “The head sets the example for the tail.”

The official New York Police Department policy is that officers should wear masks when interacting with the public. But in a statement on Wednesday, the department dismissed the criticism about the lack of masks as petty.

“Perhaps it was the heat,” Sgt. Jessica McRorie of the department’s press office said in a statement. “Perhaps it was the 15 hour tours, wearing bullet resistant vests in the sun. Perhaps it was the helmets. With everything New York City has been through in the past two weeks and everything we are working toward together, we can put our energy to a better use.”

“In a nutshell,” as they say, and here is the full NYT piece. This short vignette reflects two basic truths: first, there is a tendency to see oneself above at least some of the laws, and to follow defined procedures only selectively. Second, given the resources and constraints put on the table, such attitudes should not be entirely surprising.

Why Do Poor People Commit More Crime?

It’s well known that people with lower incomes commit more crime. Call this the cross-sectional result. But why? One set of explanations suggests that it’s precisely the lack of financial resources that causes crime. Crudely put, maybe poorer people commit crime to get money. Or, poorer people face greater strains–anger, frustration, resentment–which leads them to lash out or poorer people live in communities that are less integrated and well-policed or poorer people have access to worse medical care or education and so forth and that leads to more crime. These theories all imply that giving people money will reduce their crime rate.

A different set of theories suggests that the negative correlation between income and crime (more income, less crime) is not causal but is caused by a third variable correlated with both income and crime. For example, higher IQ or greater conscientiousness could increase income while also reducing crime. These theories imply that giving people money will not reduce their crime rate.

The two theories can be distinguished by an experiment that randomly allocates money. In a remarkable paper, Cesarini, Lindqvist, Ostling and Schroder report on the results of just such an experiment in Sweden.

Cesarini et al. look at Swedes who win the lottery and they compare their subsequent crime rates to similar non-winners. The basic result is that, if anything, there is a slight increase in crime from winning the lottery but more importantly the authors can statistically reject that the bulk of the cross-sectional result is causal. In other words, since randomly increasing a person’s income does not reduce their crime rate, the first set of theories are falsified.

A couple of notes. First, you might object that lottery players are not a random sample. A substantial part of Cesarini et al.’s lottery data, however, comes from prize linked savings accounts, savings accounts that pay big prizes in return for lower interest payments. Prize linked savings accounts are common in Sweden and about 50% of Swedes have a PLS account. Thus, lottery players in Sweden look quite representative of the population. Second, Cesarini et al. have data on some 280 thousand lottery winners and they have the universe of criminal convictions; that is any conviction of an individual aged 15 or higher from 1975-2017. Wow! Third, a few people might object that the correlation we observe is between convictions and income and perhaps convictions don’t reflect actual crime. I don’t think that is plausible for a variety of reasons but the authors also find no statistically significant evidence that wealth reduces the probability one is suspect in a crime investigation (god bless the Swedes for extreme data collection). Fourth, the analysis was preregistered and corrections are made for multiple hypothesis testing. I do worry somewhat that the lottery winnings, most of which are on the order of 20k or less are not large enough and I wish the authors had said more about their size relative to cross sectional differences. Overall, however, this looks to be a very credible paper.

In their most important result, shown below, Cesarini et al. convert lottery wins to equivalent permanent income shocks (using a 2% interest rate over 20 years) to causally estimate the effect of permanent income shocks on crime (solid squares below) and they compare with the cross-sectional results for lottery players in their sample (circle) or similar people in Sweden (triangle). The cross-sectional results are all negative and different from zero. The causal lottery results are mostly positive, but none reject zero. In other words, randomly increasing people’s income does not reduce their crime rate. Thus, the negative correlation between income and crime must be due to a third variable. As the authors summarize rather modestly:

Although our results should not be casually extrapolated to other countries or segments of the population, Sweden is not distinguished by particularly low crime rates relative to comparable countries, and the crime rate in our sample of lottery players is only slightly lower than in the Swedish population at large. Additionally, there is a strong, negative cross-sectional relationship between crime and income, both in our sample of Swedish lottery players and in our representative sample. Our results therefore challenge the view that the relationship between crime and economic status reflects a causal effect of financial resources on adult offending.

Still under-policed and over-imprisoned

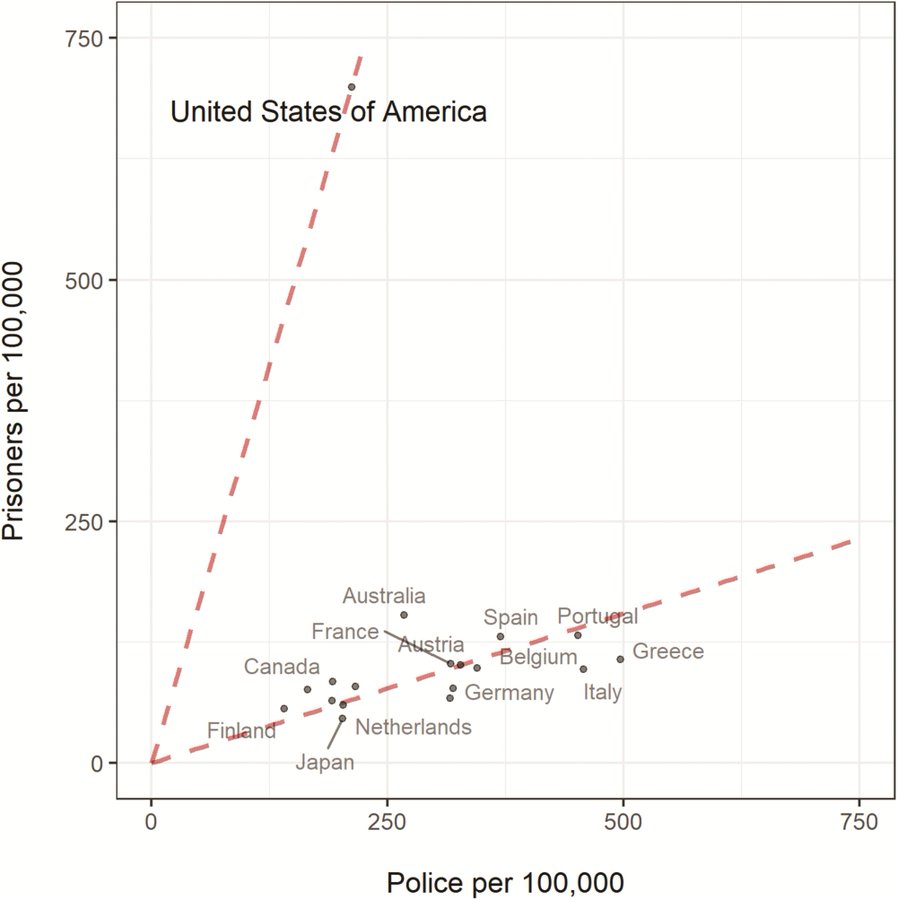

A new paper, The Injustice of Under-Policing, makes a point that I have been emphasizing for many years, namely, relative to other developed countries the United States is under-policed and over-imprisoned.

…the American criminal legal system is characterized by an exceptional kind of under-policing, and a heavy reliance on long prison sentences, compared to other developed nations. In this country, roughly three people are incarcerated per police officer employed. The rest of the developed world strikes a diametrically opposite balance between these twin arms of the penal state, employing roughly three and a half times more police officers than the number of people they incarcerate. We argue that the United States has it backward. Justice and efficiency demand that we strike a balance between policing and incarceration more like that of the rest of the developed world. We call this the “First World Balance.”

First, as is well known, the US has a very high rate of imprisonment compared to other countries but less well known is that the US has a relatively low rate of police per capita.

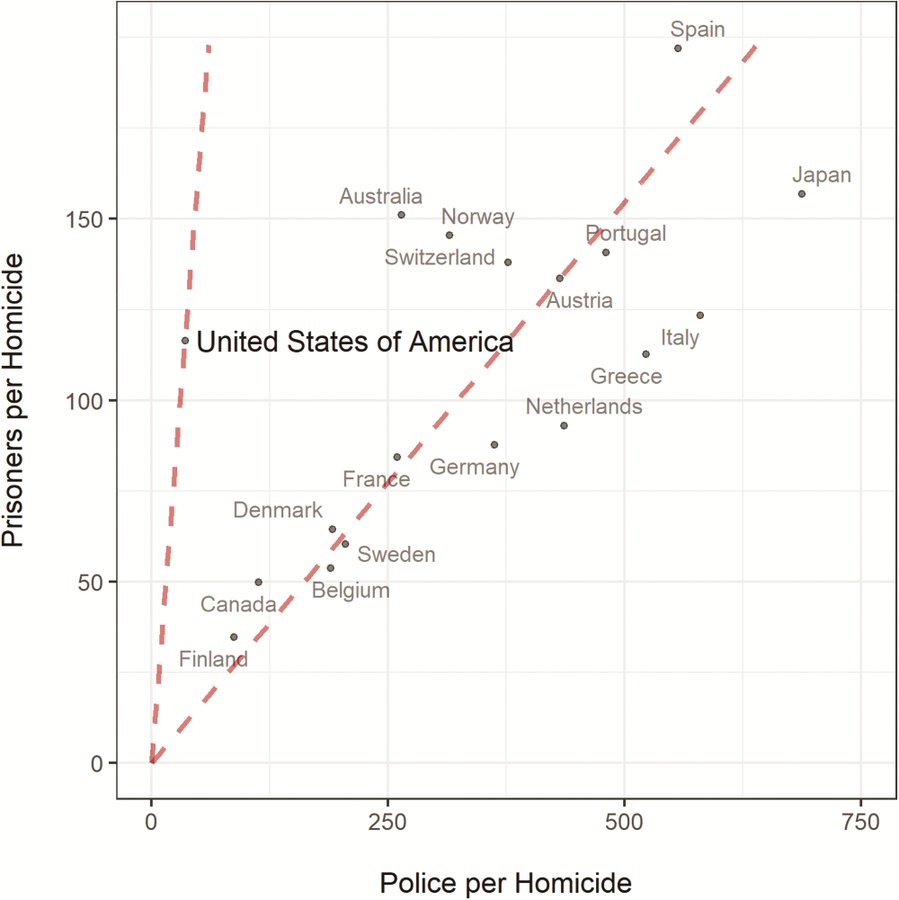

If we focus on rates relative to crime then we get a slightly different but similar perspective. Namely, relative to the number of homicides we have a normal rate of imprisonment but are still surprisingly under-policed.

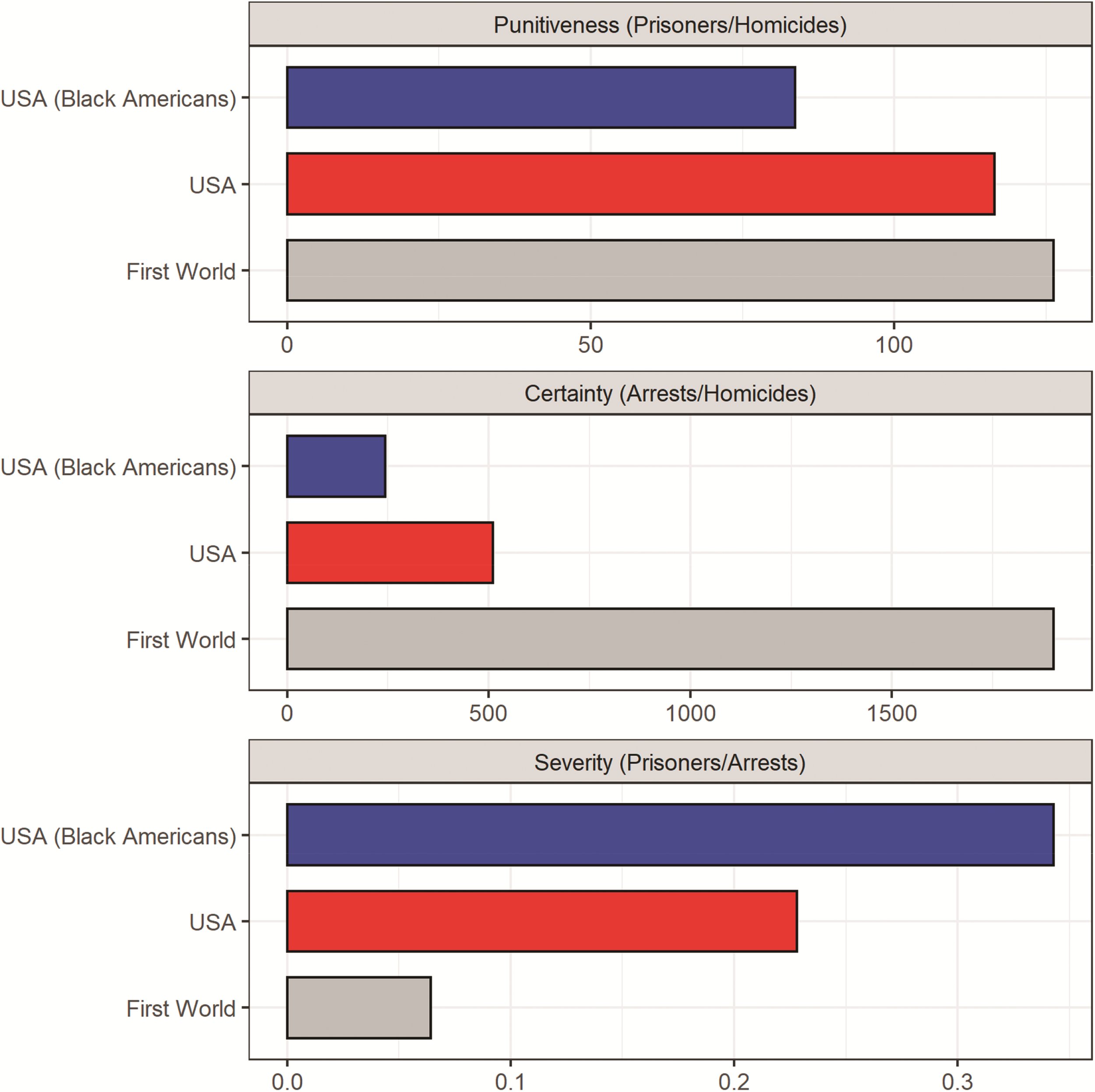

As a result, as I argued in What Was Gary Becker’s Biggest Mistake?, we have a low certainty of punishment (measured as arrests per homicide) and then try to make up for that with high punishment levels (prisoners per arrest). The low certainty, high punishment level is especially notably for black Americans.

Shifting to more police and less imprisonment could reduce crime and improve policing. More police and less imprisonment also has the advantage of being a feasible policy. Large majorities of blacks, hispanics and whites support hiring more police. “Tough on crime” can be interpreted as greater certainty of punishment and with greater certainty of punishment we can safely reduce punishment levels.

Hat tip: A thread from Justin Nix.

More guns, more crime?

The full title of the paper is “More Guns, More Unintended Consequences: The Effects of Right-to-Carry on Criminal Behavior and Policing in US Cities” and the authors are John J. Donohue, Samuel V. Cai, Matthew V. Bondy, and Philip J. Cook (does Cook get enough credit for his trajectory of ongoing productivity?) and here is the abstract:

We analyze a sample of 47 major US cities to illuminate the mechanisms that lead Right-to-Carry concealed handgun laws to increase crime. The altered behavior of permit holders, career criminals, and the police combine to generate 29 and 32 percent increases in firearm violent crime and firearm robbery respectively. The increasing firearm violence is facilitated by a massive 35 percent increase in gun theft (p=0.06), with further crime stimulus flowing from diminished police effectiveness, as reflected in a 13 percent decline in violent crime clearance rates (p=0.03). Any crime-inhibiting benefits from increased gun carrying are swamped by the crime-stimulating impacts.

Here is the link to the NBER working paper.

A new take on “defund the police”

There is less to the idea than meets the eye, do not forget the counties:

This paper finds that disbanding police departments leads to fewer police-related deaths, fewer reported crimes, and lower law enforcement expenditures. However, the number of crimes reported by the sheriff for the entire county increases by an amount commensurate to the decrease in the number of crimes reported by cities that disbanded their police department. Furthermore, disbanding police departments is associated with an increase in county sheriffs spending which offsets the city savings. Thus, disbanding police departments does not appear to impact overall crime, shifts responsibility for law enforcement onto other governments, and reduces the available information about cities’ crimes.

That is from a new paper by Richard T. Boylan, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Are nuclear weapons or Rogue AI the more dangerous risk?

I was going to write a long post on this question, as recently I had been urged to do by one of the leaders of the Effective Altruism movement, during a Sichuan lunch.

But then Putin declared a nuclear alert, and I figured a short post might be more effective. To be clear, I think the chance of nuclear weapons use right now is pretty low. But it is not zero, if only because of errors and misunderstandings. So imagine this kind of scenario repeated across a few centuries, with an increasing number of nuclear powers at that. And this time around, there is a truly existential threat to the current version of the Russian state, and a number of people are suggesting that Putin has gone a little wacko.

And this is in a world where, about one week ago, the conventional wisdom was that Russia would not really invade Ukraine at all, maybe just a limited police action in the east.

As for Rogue AI, here is a long Scott Alexander post (ungated) on the topic. For now I will just say that it makes my head hurt. It makes my head hurt because the topic is so complicated. And I don’t take any particular form of technological progress for granted, not along any time frame. That holds all the more true for “exotic” claims about what might be possible over the next few decades. Most of the history of the human race is that of zero economic growth, sometimes negative economic growth. And how good were past thinkers at predicting the future? Don’t just select on those who are famous because they got some big things right.

So I see nuclear war as the much greater large-scale risk, by far. We know nuclear weapons work and we know they can be deployed without any technological advances at all. And we know they are highly destructive by their very nature, whether we “align” them or not, whether we properly train them or not.

How many people, as public intellectuals, have made “let’s make sure all countries holding nuclear weapons can accurately distinguish between an incoming rocket and a flock of birds” their main thing? Zero?

https://twitter.com/mattyglesias/status/1498023624380403714

Are body cameras effective for constraining police after all?

Controversial police use of force incidents have spurred protests across the nation and calls for reform. Body-worn cameras (BWCs) have received extensive attention as a potential key solution. I conduct the first nationwide study of the effects of BWCs in more than 1,000 agencies. I identify the causal effects by using idiosyncratic variation in adoption timing attributable to administrative hurdles and the lengthy process to the eventual adoption at different agencies. This empirical strategy addresses limitations of previous studies that evaluated BWCs within a single agency; in a single-agency setting, the control group officers are also indirectly affected by BWCs because they interact with the treatment group officers (spillover), and agencies that give researchers access may fundamentally differ from other agencies (site-selection bias). Overcoming these limitations, my multi-agency study finds that BWCs have led to a substantial drop in the use of force, both among whites and minorities. Nationwide, they reduce police-involved homicides by 43%. Surprisingly, I do not find evidence that BWCs are associated with de-policing. Examining social media usage data from Twitter as well as data on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, I find that after BWC adoption, public opinion toward the police improves. These findings imply that BWCs can be an important tool for improving police accountability without sacrificing policing capabilities.

That is from a new paper by Taeho Kim, on the job market from the University of Chicago, a Steve Levitt student. The piece has a revise and resubmit from ReStat.

How is Defunding the Police Going in Minneapolis?

Not well.

MPR News: The meeting was slated as a Minneapolis City Council study session on police reform.

But for much of the two-hour meeting, council members told police Chief Medaria Arradondo that their constituents are seeing and hearing street racing which sometimes results in crashes, brazen daylight carjackings, robberies, assaults and shootings. And they asked Arradondo what the department is doing about it.

…Just months after leading an effort that would have defunded the police department, City Council members at Tuesday’s work session pushed chief Medaria Arradondo to tell them how the department is responding to the violence…More people have been killed in the city in the first nine months of 2020 than were slain in all of last year. Property crimes, like burglaries and auto thefts, are also up. Incidents of arson have increased 55 percent over the total at this point in 2019.

Bear in mind this is coming after just a few months of reduced policing, due in part to extra demands and difficulty and probably in part due to police pulling back either out of fear or reluctance (blue flu) as also happened in Baltimore after the Freddie Gray killing and consequent protests and riots.

A few true believers still remain:

Cunningham also criticized some of his colleagues for seeming to waver on the promises they made earlier this year to transform the city’s public safety system.

“What I am sort of flabbergasted by right now is colleagues, who a very short time ago were calling for abolition, are now suggesting we should be putting more resources and funding into MPD,” Cunningham said.

I’m a supporter of unbundling the police and improving policing but the idea that we can defund the police and crime will just melt away is a fantasy. As with bail reform the defunders risk a backlash. Let’s start by decriminalizing more victimless crimes, as we have done in many states with marijuana laws. Let’s work on creating bureaus of road safety. But one of the reasons we do these things is so that we can increase the number of police on the street. The United States is underpoliced and the consequences of underpolicing, as well as overpolicing, fall on minority communities. As I have argued before, we need better policing so that we can all be comfortable with more policing. Getting there, however, will take time.

Unbundling the Police in Kentucky

In Why Are the Police in Charge of Road Safety? I argued for unbundling the police:

Don’t use a hammer if you don’t need to pound a nail…the police have no expertise in dealing with the mentally ill or with the homeless–jobs like that should be farmed out to other agencies. Notice that we have lots of other safety issues that are not handled by the police. Restaurant inspectors, for example, do over a million restaurant inspectors annually but they don’t investigate murder or drug charges and they are not armed. Perhaps not coincidentally, restaurant inspectors are not often accused of inspector brutality, “Your honor, I swear I thought he was reaching for a knife….”.

A small experiment was started several years ago in Alexandria, Kentucky.

Faced with a tight budget and rising demands on its 17 officer police department, the City of Alexandria in Campbell County tried something different. Instead of hiring an additional officer and taking on the added expenses of equipping that officer, the police chief at the time hired a social worker to respond in tandem with officers.

Anecdotally the results appear good:

“It was close to a $45,000 to $50,000 annual savings from hiring a police officer the first time to hiring a social worker,” [former Alexandria Police Department chief] Ward said. “They (police social workers) started solving problems for people in our community and for our agency that we’ve never been able to solve before.”

Ward believes the results in Alexandria, a city of less than 10,000, could be replicated in larger cities like Louisville, where officers respond to calls involving mental health, domestic disturbances, and homelessness an average of once every 10 minutes.

“Louisville is very big with services,” Pompilio said. “They have lots of things to offer families. It’s just a matter of a social worker connecting.”

Alexandria doubled down on its commitment and now employs two full-time social workers to work and respond with its 17 officers.

Hat tip: NextDraft.

Mood affiliation, the police, and rising crime rates

Had a thought on the discussion of rising crime over the last few months inspired by your MR posts on mood affiliation that I wanted to pass along:

There’s been a bit of discussion lately about increased shootings in major cities in the wake of the George Floyd protests, and the two main narratives trying to explain them have been “protests fueling higher tensions” and “cops backing off and not patrolling as much or doing their jobs”. Interestingly, the latter seems to be based on a model where fewer cops and patrols results in more crime, so you might naively expect people who hold that belief would be more likely to believe that simple defunding and reduction of police presence would lead to more crime generally.

But if you believe that mood affiliation predicts opinions better than factual consistency, then it matters more that the former position sounds like “cops to blame, cops bad”, while the second sounds more like “cops are important, cops good”. And most commentators care more about the correct affect towards the police, rather than consistent models of reality, so you largely have commentators that are pro-defund police, but blame their lack of presence for crime increases, or commentators that are pro-police, think defunding would lead to increases in crime, but are less willing to entertain the idea that recent increases in crime are caused by the choices of officers.

That is from an email by Benjamin Hawley.

When Police Kill

When Police Kill is the 2017 book by criminologist Franklin Zimring. Some insights from the book.

Official data dramatically undercount the number of people killed by the police. Both the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Arrest-Related Deaths and the FBI’s Supplemental Homicide Reports estimated around 400-500 police kills a year, circa 2010. But the two series have shockingly low overlap–homicides counted in one series are not counted in the other and vice-versa. A statistical estimate based on the lack of overlap suggests a true rate of around 1000 police killings per year.

The best data come from newspaper reports which also show around 1000-1300 police killings a year (Zimring focuses his analysis on The Guardian’s database.) Fixing the data problem should be a high priority. But the FBI cannot be trusted to do the job:

The best data come from newspaper reports which also show around 1000-1300 police killings a year (Zimring focuses his analysis on The Guardian’s database.) Fixing the data problem should be a high priority. But the FBI cannot be trusted to do the job:

Unfortunately, the FBI’s legacy of passive acceptance of incomplete statistical data on police killings, its promotion of the self-interested factual accounts from departments, and its failure to collect significant details about the nature of the provocation and the nature of the force used by police suggest that nothing short of massive change in its orientation, in its legal authority to collect data and its attitude toward auditing and research would make the FBI an agency worthy of public trust and statistical reliability in regard to the subject of this book.

The FBI’s bias is even seen in its nomenclature for police killings–“justifiable homicides”–which some of them certainly are not.

The state kills people in two ways, executions and police killings. Executions require trials, appeals, long waiting periods and great deliberation and expense. Police killings are not extensively monitored, analyzed or deliberated upon and, until very recently, even much discussed. Yet every year, police kill 25 to 50 times as many people as are executed. Why have police killings been ignored?

When an execution takes place in Texas, everybody knows that Texas is conducting the killing and is accountable for its consequences. When Officer Smith kills Citizen Jones on a city street in Dallas, it is Officer Smith rather than any larger governmental organization…[who] becomes the primary repository of credit or blame.

We used to do the same thing with airplane crashes and medical mistakes–that is, look for pilot or physician error. Safety didn’t improve much until we started to apply systems thinking. We need a systems-thinking approach to police shootings.

Police kill males (95%) far more than females, a much larger ratio than for felonies. Police kill more whites than blacks which is often forgotten, although not surprising because whites are a larger share of the population. Based on the Guardian data shown in Zimring’s Figure 3.1, whites and Hispanics are killed approximately in proportion to population. Blacks are killed at about twice their proportion to population. Asians are killed less than in proportion to their population.

A surprising finding:

Crime is a young man’s game in the United States but being killed by a police officer is not.

The main reason for this appears to be that a disproportionate share of police killings come from disturbance calls, domestic and non-domestic about equally represented. A majority of the killings arising from disturbance calls are of people aged forty or more.

The tendency of both police and observers to assume that attacks against police and police use of force is closely associated with violent crime and criminal justice should be modified in significant ways to accord for the disturbance, domestic conflicts, and emotional disruptions that frequently become the caseload of police officers.

A slight majority (56%) of the people who are killed by the police are armed with a gun and another 3.7% seemed to have a gun. Police have reason to fear guns, 92% of killings of police are by guns. But 40% of the people killed by police don’t have guns and other weapons are much less dangerous to police. In many years, hundreds of people brandishing knives are killed by the police while no police are killed by people brandishing knives. The police seem to be too quick to use deadly force against people significantly less well-armed than the police. (Yes, Lucas critique. See below on policing in a democratic society).

Police kill more people than people kill police–a ratio of about 15 to 1–and the ratio has been increasing over time. Policing has become safer over the past 40 years with a 75% drop in police killed on the job since 1976–the fall is greater than for crime more generally and is probably due to Kevlar vests. Kevlar vests are an interesting technology because they make police safer without imposing more risk on citizens. We need more win-win technologies. Although policing has become safer over time, the number of police killings has not decreased in proportion which is why the “kill ratio” has increased.

A major factor in the number of deaths caused by police shootings is the number of wounds received by the victim. In Chicago, 20% of victims with one wound died, 34% with two wounds and 74% with five or more wounds. Obvious. But it suggests a reevaluation of the police training to empty their magazine. Zimring suggests that if the first shot fired was due to reasonable fear the tenth might not be. A single, aggregational analysis:

…simplifies the task of police investigator or district attorney, but it creates no disincentive to police use of additional deadly force that may not be necessary by the time it happens–whether with the third shot or the seventh or the tenth.

It would be hard to implement this ex-post but I agree that emptying the magazine isn’t always reasonable, especially when the police are not under fire. Is it more dangerous to fire one or two shots and reevaluate than to fire ten? Of course, but given the number of errors police make this is not an unreasonable risk to ask police to take in a democratic society.

The successful prosecution of even a small number of extremely excessive force police killings would reduce the predominant perception among both citizens and rank-and-file police officers that police have what amounts to immunity from criminal liability for killing citizens in the line of duty.

Prosecutors, however, rely on the police to do their job and in the long-run won’t bite the hand that feeds them. Clear and cautious rules of engagement that establish bright lines would be more helpful. One problem is that police are protected because police brutality is common (somewhat similar to my analysis of riots).

The more killings a city experiences, the less likely it will be that a particular cop and a specific killings can lead to a charge and a conviction. In the worst of such settings, wrongful killings are not deviant officer behavior.

…clear and cautious rules of engagement will …make officers who ignore or misapply departmental standards look more blameworthy to police, to prosecutors, and to juries in the criminal process.

Police kill many more people in the United States than in other developed countries, even adjusting for crime rates (where the U.S. is less of an outlier than most people imagine). The obvious reason is that there are a lot of guns in the United States. As a result, the United States is not going to get its police killing rate down to Germany’s which is at least 40 times lower. Nevertheless:

[Police killings]…are a serious problem we can fix. Clear administrative restrictions on when police can shoot can eliminate 50 to 80 percent of killings by police without causing substantial risk to the lives of police officers or major changes in how police do their jobs. A thousand killings a year are not the unavoidable result of community conditions or of the nature of policing in the United States.

Ubundling the Police in NYC

In Why Are the Police in Charge of Road Safety? I argued for unbundling the police–i.e. taking some of the tasks traditionally assigned to police such as road safety and turning them over to unarmed agencies more suited to the task. A new report from Transportation Alternatives adds to the case. The report notes that the police in NYC aren’t even doing a good job on road safety.

For example, in 2017, there were 46,000 hit-and-run crashes in New York City. Yet police officers arrested just one percent of all hit-and-run drivers. In the past five years, hit-and-run crashes in New York City have increased by 26 percent. By comparison, DOT infrastructure projects designed to reduce these traffic crashes have proven effective and scalable.

Streetsblog (cited in the report and quoted here) also notes this remarkable fact:

Streetsblog recently reported that of the 440 tickets police issued to people for biking on the sidewalk in 2018 and 2019, 374 — or 86.4 percent — of those where race was listed went to Black and Hispanic New Yorkers. The wildly disproportionate stats followed another report showing that cops issued 99 percent of jaywalking tickets to Black and Hispanic people in the first quarter of this year.

Not From the Onion: Grenade Launchers for School Police

LATimes: Los Angeles Unified school police officials said Tuesday that the department will relinquish some of the military weaponry it acquired through a federal program that furnishes local law enforcement with surplus equipment. The move comes as education and civil rights groups have called on the U.S. Department of Defense to halt the practice for schools.

The Los Angeles School Police Department, which serves the nation’s second-largest school system, will return three grenade launchers but intends to keep 61 rifles and a Mine Resistant Ambush Protected armored vehicle it received through the program.

A school police department with grenade launchers and a Mine Resistant Ambush Protected armored vehicle! Only in America.

The article is from 2014 but relevant to current discussions of militarized police.

Hat tip: Noah Smith.