Results for “opioid” 65 found

Why hasn’t the opioid epidemic converged to manageable levels?

There is a new NBER working paper on this very good question by David M. Cutler and J. Travis Donahoe:

Opioid overdose death rates in the United States have risen continuously for over three decades, increasing 2,142 percent in total from 1990 to 2020. This is surprising. One might expect drug epidemics to be self-limiting, as policy and individual behavior reacts to observed deaths. We study why opioid deaths have risen so greatly and for so long. We consider three reasons for a prolonged epidemic: exogenous and continuing changes in demand or supply, and spillovers in demand for opioids across users, which we term “thick market externalities.” We show there is no evidence of sufficiently large exogenous changes in the demand or supply of opioids that could explain such a prolonged increase in death rates. We test for spillovers using county-level data on opioid deaths from 1991–2018 and opioid shipments from 2006–2009, combined with data on friendships and distance between counties. Estimating a model with addiction and spatial spillovers, we find large spillovers in opioid use and deaths across areas. A shock that increases opioid death rates by 1 in an index county causes 0.38 to 0.76 more deaths in other counties because of spillovers. Because opioids are addictive, this leads to even more deaths and spillovers in future years. In some specifications, these effects are large enough to generate a continuously increasing epidemic without any ongoing changes in demand or supply. We estimate spillovers explain 84 to 92 percent of opioid deaths from 1990 to 2018 and are the main reason deaths have increased for so long.

Is there any way to make the spillovers in demand less strong?

The Role of Friends in the Opioid Epidemic

Your friends are not always good for you:

The role of friends in the US opioid epidemic is examined. Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health), adults aged 25-34 and their high school best friends are focused on. An instrumental variable technique is employed to estimate peer effects in opioid misuse. Severe injuries in the previous year are used as an instrument for opioid misuse in order to estimate the causal impact of someone misusing opioids on the probability that their best friends also misuse. The estimated peer effects are significant: Having a best friend with a reported serious injury in the previous year increases the probability of own opioid misuse by around 7 percentage points in a population where 17 percent ever misuses opioids. The effect is driven by individuals without a college degree and those who live in the same county as their best friends.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Effrosyni Adamopoulou, Jeremy Greenwood, Nezih Guner, and Karen Kopecky.

Carrying opioids in legal imports?

The U.S. opioid crisis is now driven by fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that currently accounts for 90% of all opioid deaths. Fentanyl is smuggled from abroad, with little evidence on how this happens. We show that a substantial amount of fentanyl smuggling occurs via legal trade flows, with a positive relationship between state-level imports and drug overdoses that accounts for 15,000-20,000 deaths per year. This relationship is not explained by geographic differences in “deaths of despair,” general demand for opioids, or job losses from import competition. Our results suggest that fentanyl smuggling via imports is pervasive and a key determinant of opioid problems

That is from a new NBER working paper by Timothy J. Moore, William W. Olney, and Benjamin Hansen. One core lesson seems to be that interdiction is largely a futile endeavor.

The Effect of Organizations on Physician Prescribing Opioids

Here is one of the more important IO papers in recent times:

In theory, there are several reasons why physician organizational form might affect the price, quantity, and quality of physician services. In this paper, we examine the effect of three aspects of physician organizational form on opioid prescribing: the number of physicians in the physician’s group (if any); the physician’s integration with or employment by a hospital or hospital system; and the average age of the other physicians in the physician’s group. We present three key findings. First, all else held constant, group physicians prescribe far fewer opioids, and prescribe them more appropriately, than do solo physicians. Second, although physicians who are employed by a hospital or practice in a hospital-owned group prescribe fewer opioids than do independent physicians, there is evidence that this difference may be due to differences in the other characteristics of physicians who are hospital-integrated rather than a causal effect. Third, we find substantial peer effects on opioid prescribing. Physicians in groups with a higher average age (excluding the physician him- or herself) prescribe more intensively and are more likely to write inappropriate opioid prescriptions than physicians in younger groups – holding constant the physician’s own age and other characteristics of his or her group.

That is from a new NBER working paper by M. Kate Bundorf, Daniel Kessler, and Sahil Lalwani.

What has been driving America’s opioid problem?

Matt Yglesias had an excellent (gated) Substack on this question lately, now Jeremy Greenwood, Nezih Guner and Karen A. Kopecky have a new and quite valuable paper. I found this to be the most interesting segment:

Through the eyes of the model, there were two key forces. The first force is the decline in prices for bot prescription and black market opioids. This had a big effect. The second force is the increase in the dosages per prescription meted out by doctors. This also had a significant impact. The fact that doctors kept pain sufferers on prescription opioids for a longer period of time had little effect. Last, an analysis is conducted on medical interventions that reduce either the probability of becoming addicted or the odds of an addict dying from an overdose. Reducing the odds of addiction can result in even more deaths due to the rise in users.

The opioid problem is a very difficult one to solve! I should stress that the paper has other results of interest.

Opioid deaths are not mainly about prescription opioids

A recent study of opioid-related deaths in Massachusetts underlines this crucial point, finding that prescription analgesics were detected without heroin or fentanyl in less than 17 percent of the cases. Furthermore, decedents had prescriptions for the opioids that showed up in toxicology tests just 1.3 percent of the time.

Alexander Walley, an associate professor of medicine at Boston University, and five other researchers looked at nearly 3,000 opioid-related deaths with complete toxicology reports from 2013 through 2015. “In Massachusetts, prescribed opioids do not appear to be the major proximal cause of opioid-related overdose deaths,” Walley et al. write in the journal Public Health Reports. “Prescription opioids were detected in postmortem toxicology reports of fewer than half of the decedents; when opioids were prescribed at the time of death, they were commonly not detected in postmortem toxicology reports….The major proximal contributors to opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts during the study period were illicitly made fentanyl and heroin.”

The study confirms that the link between opioid prescriptions and opioid-related deaths is far less straightforward than it is usually portrayed. “Commonly the medication that people are prescribed is not the one that’s present when they die,” Walley told Pain News Network. “And vice versa: The people who died with a prescription opioid like oxycodone in their toxicology screen often don’t have a prescription for it.”

That is by Jacob Sullum at Reason, via Arnold Kling.

Opioids and labor market participation

The onset of the opioid crisis coincided with the beginning of nearly 15 years of declining labor force participation in the US. Furthermore, the areas most affected by the crisis have generally experienced the worst deteriorations in labor market conditions. Despite these time series and cross-sectional correlations, there is little agreement on the causal effect of opioids on labor market outcomes. I provide new evidence on this question by leveraging a natural experiment which sharply decreased the supply of hydrocodone, one of the most commonly prescribed opioids in the US. I identify the causal impact of this decrease by exploiting pre-existing variation in the extent to which different types of opioids were prescribed across geographies to compare areas more and less exposed to the treatment over time. I find that areas with larger reductions in opioid prescribing experienced relative improvements in employment-to-population ratios, driven primarily by an increase in labor force participation. The regression estimates indicate that a 10 percent decrease in hydrocodone prescriptions increased the employment-to-population ratio by about 0.7 percent. These findings suggest that policies which reduce opioid misuse may also have positive spillovers on the labor market.

That is from a job market paper by David Beheshti at the University of Texas at Austin.

Do opioids contribute to social bonding?

It seems so (uh-oh):

Close social bonds are critical to immediate and long-term well-being. However, the neurochemical mechanisms by which we remain connected to our closest loved ones are not well understood. Opioids have long been theorized to contribute to social bonding via their actions on the brain. But feelings of social connection toward one’s own close others and direct comparisons of ventral striatum (VS) activity in response to close others and strangers, a neural correlate of social bonding, have not been explored. Therefore, the current clinical trial examined whether opioids causally affect neural and experiential signatures of social bonding. Eighty participants were administered naltrexone (n = 40), an opioid antagonist that blocks natural opioid processing, or placebo (n = 40) before completing a functional MRI scan where they viewed images of their close others and individuals they had not seen before (i.e., strangers). Feelings of social connection to the close others and physical symptoms commonly experienced when taking naltrexone were also collected. In support of hypotheses, naltrexone (vs. placebo) reduced feelings of social connection toward the close others (e.g., family, friends, romantic partners). Furthermore, naltrexone (vs. placebo) reduced left VS activity in response to images of the same close others, but did not alter left VS activity to strangers. Finally, the positive correlation between feelings of connection and VS activity to close others present in the placebo condition was erased by naltrexone. Effects remained after adjusting for physical symptoms. Together, results lend support to theories suggesting that opioids contribute to social bonding, especially with our closest loved ones.

Here is the full article, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. Note the top item behind the Lewis link: “We find zero or modestly positive estimated effects of these [Haitian] migrants on the educational outcomes of incumbent students in the year of the earthquake or in the 2 years that follow, regardless of the socioeconomic status, grade level, ethnicity, or birthplace of incumbent students.”

How Much Did Physicians Drive the Opioid Crisis?

It’s well known that the opioid crisis started with prescription abuse but how much abuse was driven by patients who fooled their physicians and how much was driven by physicians who responded to monetary incentives with a nod and a wink? Molly Schnell provides some evidence which even a hard headed rationalist like myself found startling.

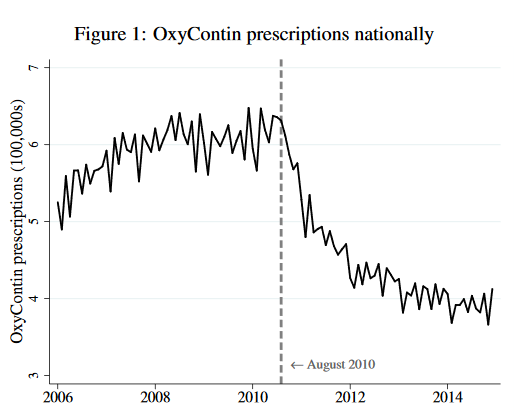

In August of 2010, Purdue Pharma replaced old OxyContin with a new, anti-abuse version of OxyContin. The new version was just as good at reducing pain as the old but it was more difficult to turn it into an injectable to produce a high. If physicians are altruists who balance treating their patient’s pain against their fear of patient addiction and downstream abuse then they should increase their prescriptions of new Oxy. From the point of view of health, the new Oxy is simply a better drug and with less abuse to worry about altruistic physicians should be more willing on the margin to prescribe Oxy to reduce pain. So what happened? Prescriptions for Oxy fell immediately and dramatically when the better version was released.

In August of 2010, Purdue Pharma replaced old OxyContin with a new, anti-abuse version of OxyContin. The new version was just as good at reducing pain as the old but it was more difficult to turn it into an injectable to produce a high. If physicians are altruists who balance treating their patient’s pain against their fear of patient addiction and downstream abuse then they should increase their prescriptions of new Oxy. From the point of view of health, the new Oxy is simply a better drug and with less abuse to worry about altruistic physicians should be more willing on the margin to prescribe Oxy to reduce pain. So what happened? Prescriptions for Oxy fell immediately and dramatically when the better version was released.

Now, to be fair to the physicians, patients who wanted to abuse Oxy stopped demanding it after the new version was released and physicians might not have realized how many of their prescriptions were being abused or sold on the secondary market. The aggregate data, which is a combination of supply and demand shifts, can mask individual physician behavior. Schnell, however, has data on the prescribing behavior of about 100,000 individual physicians who prescribed opioids.

Schnell finds that nearly a third of physicians behaved exactly as the altruism theory predicts. Namely, when new Oxy was released these altruistic physicians increased their prescriptions of Oxy and they maintained or reduced their prescriptions of other opioids. In fact, the median altruistic physician doubled their prescriptions of the new and improved Oxy. But almost 40% of physicians in Schnell’s sample behaved in a decidedly non-altruistic manner. Beginning in August of 2010, these non-altruistic physicians halved their prescriptions of new and improved Oxy and increased their prescriptions of other opioids. It’s difficult to see how attentive and altruistic physicians could decrease their demand for a better drug.

Schnell also finds that some parts of the country had fewer altruistic physicians and the consequences are evident in mortality statistics:

…. these differences in physician altruism across commuting zones translate into significant differences in mortality across locations…a one standard deviation increase in low-altruism physicians is associated with a 0.33 standard deviation increase in deaths involving drugs per capita. While this association is reduced conditional on observable commuting zone characteristics (including race, age, education, and income profiles), a significant and large association between the share of low-altruism physicians and drug-related mortality remains. Furthermore…this relationship persists even conditional on the number of opioid prescriptions, suggesting that the association is driven by the allocation of prescriptions introduced by low-altruism physicians rather than simply the quantity.

The less-altruistic physicians increased prescriptions for other opioids after new Oxy was introduced but perhaps even this was better than the non-prescription alternatives like heroin and street fentanyl. Indeed, Alpert, Powell and Pacula show that the introduction of improved Oxy led to more deaths because people switched to more dangerous, illegal alternatives. So was it a bad idea to introduce a better drug? Maybe, but if new Oxy had been introduced earlier perhaps fewer people would have been addicted, leading to less demand for illegal markets later. Thus, static and dynamic effects may differ. The economics of dual use goods is complicated.

Opioids and the Labor Market

Do not believe those who tell you the only labor market problems have been demand side!:

This paper studies the relationship between local opioid prescription rates and labor market outcomes. We improve the joint measurement of labor market outcomes and prescription rates in the rural areas where nearly 30 percent of the US population lives. We find that increasing the local prescription rate by 10 percent decreases the prime-age employment rate by 0.50 percentage points for men and 0.17 percentage points for women. This effect is larger for white men with less than a BA (0.70 percentage points) and largest for minority men with less than a BA (1.01 percentage points). Geography is an obstacle to giving a causal interpretation to these results, especially since they were estimated in the midst of a large recession and recovery that generated considerable cross-sectional variation in local economic performance. We show that our results are not sensitive to most approaches to controlling for places experiencing either contemporaneous labor market shocks or persistently weak labor market conditions. We also present evidence on reverse causality, finding that a short-term unemployment shock did not increase the share of people abusing prescription opioids. Our estimates imply that prescription opioids can account for 44 percent of the realized national decrease in men’s labor force participation between 2001 and 2015.

The fact that the demand side blade of the scissors can be powerful does not imply the supply side blade does not matter, no matter how many snide tweets you may read to the contrary.

The paper is by Dionissi Aliprantis, Kyle Fee, and Mark E. Schweitzer at the Cleveland Fed.

Via Ilya Novak.

Opioids are not mainly an economic phenomenon

Overall, our findings suggest that there is no simple causal relationship between economic conditions and the abuse of opioids. Therefore, while improving economic conditions in depressed areas is desirable for many reasons, it is unlikely to curb the opioid epidemic.

That is from Janet Currie, Jonas Y. Jin, and Molly Schnell in a new NBER working paper.

Alan Krueger on opioids and labor force participation

I haven’t had a chance to look at this one, but here is the headline summary from Brookings:

The new paper, published in the Fall 2017 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, makes a strong case for looking at the opioid epidemic as one driver of declining labor force participation rates.

In fact, Krueger suggests that the increase in opioid prescriptions from 1999 to 2015 could account for about 20 percent of the observed decline in men’s labor force participation during that same period, and 25 percent of the observed decline in women’s labor force participation.

Here is the Brookings link.

Opioids for the masses?

This has long seemed to me an understudied topic, so I was interested to read the job market paper of Angela E. Kilby, who is on the market this year from MIT. And she does what I like to see in a paper, namely try to figure out whether some practice or institution is actually worth it.

The background is this: “…In the face of concerns that undertreatment of pain was a “serious public health issue,” medically indicated use of these drugs over the past 15 years has increased dramatically, and attitudes have liberalized towards the use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain.”

When it comes to the increased use of opioids, she finds the following trade-offs:

1. Since 1999, there has been a fourfold increase in drug overdose deaths linked to opiod pain relievers. In 2013, the number of opiate-linked overdose deaths was 25,117, a higher number than I was expecting. (But note that most of these can no longer be reduced by the feasible interventions under consideration.)

2. The increased use of opioids seems to pass a cost-benefit test, compared to the passage of a tougher Prescription Monitoring Plan. With a host of caveats and qualifiers, she measures the pain reduction and other benefits from looser regulation at $12.1 billion a year and the costs of higher addiction rates, again from looser regulation, at $7.3 billion per year.

There is much more to it than what I am reporting, and in general I believe economists do not devote enough attention to studying the topic of pain.

The Adderall Shortage: DEA versus FDA in a Regulatory War

A record number of drugs are in shortage across the United States. In any particular case, it’s difficult to trace out the exact causes of the shortage but health care is the US’s most highly regulated, socialist industry and shortages are endemic under socialism so the pattern fits. The shortage of Adderall and other ADHD medications is a case in point. Adderall is a Schedule II controlled substance which means that in addition to the FDA and other health agencies the production of Adderall is also regulated, monitored and controlled by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The DEA aims to “combat criminal drug networks that bring harm, violence, overdoses, and poisonings to the United States.” Its homepage displays stories of record drug seizures, pictures of “most wanted” criminal fugitives, and heroic armed agents conducting drug raids. With this culture, do you think the DEA is the right agency to ensure that Americans are also well supplied with legally prescribed amphetamines?

The DEA aims to “combat criminal drug networks that bring harm, violence, overdoses, and poisonings to the United States.” Its homepage displays stories of record drug seizures, pictures of “most wanted” criminal fugitives, and heroic armed agents conducting drug raids. With this culture, do you think the DEA is the right agency to ensure that Americans are also well supplied with legally prescribed amphetamines?

Indeed, there is a large factory in the United States capable of producing 600 million doses of Adderall annually that has been shut down by the DEA for over a year because of trivial paperwork violations. The New York Magazine article on the DEA created shortage has to be read to be believed.

Inside Ascent’s 320,000-square-foot factory in Central Islip, a labyrinth of sterile white hallways connects 105 manufacturing rooms, some of them containing large, intricate machines capable of producing 400,000 tablets per hour. In one of these rooms, Ascent’s founder and CEO — Sudhakar Vidiyala, Meghana’s father — points to a hulking unit that he says is worth $1.5 million. It’s used to produce time-release Concerta tablets with three colored layers, each dispensing the drug’s active ingredient at a different point in the tablet’s journey through the body. “About 25 percent of the generic market would pass through this machine,” he says. “But we didn’t make a single pill in 2023.”

… the company has acknowledged that it committed infractions. For example, orders struck from 222s must be crossed out with a line and the word cancel written next to them. Investigators found two instances in which Ascent employees had drawn the line but failed to write the word.

The causes of the DEA’s crackdown appears to be precisely the contradiction in its dueling missions. Ascent also produces opioids and the DEA crackdown was part of what it calls Operation Bottleneck, a series of raids on a variety of companies to demand that they account for every pill produced.

The causes of the DEA’s crackdown appears to be precisely the contradiction in its dueling missions. Ascent also produces opioids and the DEA crackdown was part of what it calls Operation Bottleneck, a series of raids on a variety of companies to demand that they account for every pill produced.

To be sure, the opioid epidemic is a problem but the big, multi-national plants are not responsible for fentanyl on the streets and even in the early years the opioid epidemic was a prescription problem (with some theft from pharmacies) not a factory theft problem (see figure at left). Maybe you think Adderall is overprescribed. Could be but the DEA is supposed to be enforcing laws not making drug policy. The one thing one can say for certain is that Operation Bottleneck has surely been a success in creating shortages of Adderall.

The DEA’s contradictory role in both combating the illegal drug trade and regulating the supply of legal, prescription drugs is highlighted by the fact that at the same as the DEA was raiding and shutting down Ascent, the FDA was pleading with them to increase production!

For Ascent, one of the more frustrating parts of being told by the government to stop making Adderall is that other parts of the government have pleaded with the company to make more. The company says that on multiple occasions, officials from the FDA asked it to increase production in response to the shortage, and that Ron Wyden, the Democratic senator from Oregon, also pressed Ascent for help. They received responses similar to those the company gave the stressed-out callers looking for pills: Ascent didn’t have any information. Instead, the company directed them to the DEA.