Results for “train like an athlete” 12 found

Learn like an athlete, knowledge workers should train

LeBron James didn’t always have thick calves, a raging six-pack, and arms like the Incredible Hulk.

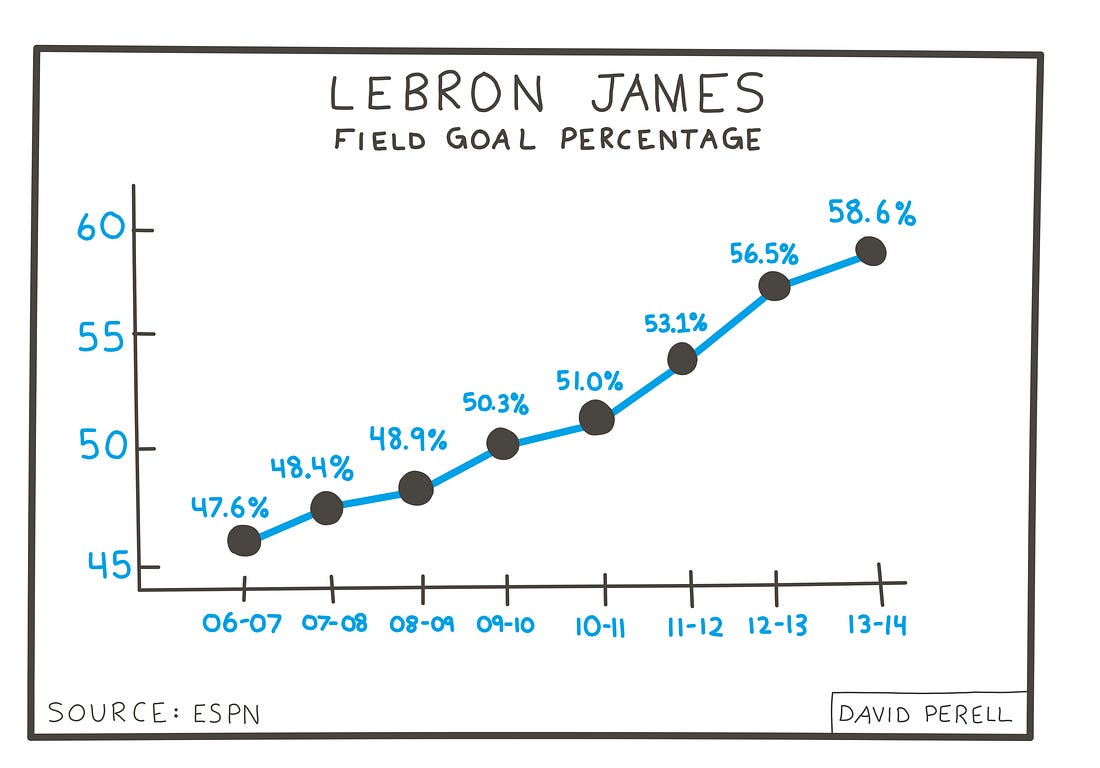

Ask LeBron about his off-season training regimen, and he’ll share a detailed run-down of his workout plan and on-the-court practice routine. When he entered the NBA, LeBron wasn’t a strong shooter. I’d bet the house that early in his career, LeBron built his off-season training regimen around his weak jump shot and disappointing 42% field goal percentage during his rookie season. As his Instagram posts reveal, LeBron worked for his strength, agility, impeccable history of injury avoidance, and an outstanding 54% field goal percentage during his 14th NBA season.

Athletes train. Musicians train. Performers train. But knowledge workers don’t.

Knowledge workers should train like LeBron, and implement strict “learning plans.” To be sure, intellectual life is different from basketball. Success is harder to measure and the metrics for improvement aren’t quite as clear. Even then, there’s a lot to learn from the way top athletes train. They are clear in their objectives and deliberate in their pursuit of improvement.

Knowledge workers should imitate them.

That is from David Perell, more at the link. Recently, one of my favorite questions to bug people with has been “What is it you do to train that is comparable to a pianist practicing scales?” If you don’t know the answer to that one, maybe you are doing something wrong or not doing enough. Or maybe you are (optimally?) not very ambitious?

Who gains and loses from the new AI?

With so many spectacular AI developments coming out this year, it is worth asking who benefits and who loses.

Specific technologies usually help some personality types and hurt others. For instance, the rise of computers, programming, and the internet helped analytical nerds. Today, you might be in high demand as a programmer or run your own start-up and earn riches. But back in the 1960s, you might have been lucky to get a job at NASA and pull in a middle-class income. Earlier, the rise of manufacturing and factory employment helped able-bodied male laborers who had an enthusiasm for physical labor.

One striking feature of the new AI systems is that you have to sit down to use them. Think of ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, and related services as individualized tutors, among their other functions. They can teach you mathematics, history, how to write better and much more. But none of this knowledge is imparted automatically. There is a relative gain for people who are good at sitting down in the chair and staying focused on something. Initiative will become more important as a quality behind success.

The returns to durability of effort are rising as well. If you quit in the middle of executing your AI-aided concrete project, the new AI services will, for you, end up as playthings rather than investments in your future.

The returns to factual knowledge are falling, continuing a trend that started with databases, search engines and Wikipedia. It is no longer so profitable to be a lawyer who knows a large amount of accumulated case law. Instead, the skills of synthesis and persuasion are more critical for success.

ChatGPT excels at producing ordinary, bureaucratic prose, written in an acceptable but non-descript style. In turn, we are likely to better understand how much of our society is organized around that basis, from corporate brochures to regulations to second-tier journalism. The rewards and status will go down for those who produce such writing today, and the rewards for exceptional originality are likely to rise. What exactly can you do to stand out from the froth of the chat bots?

Our underlying views may become more elitist. If you are a programmer who is only slightly better than the bots, you may lose respect and income. The exceptional programmers and writers, who cannot readily be copied, will command more attention and status. And as successive generations of the GPTs improve, these rewards will be doled out to a smaller and smaller percentage of humans.

It is charged that the new bots do not have originality. However true that may be, the observation eventually focuses your attention on the question of how many humans have that same originality.

Most writers are likely to lose some of their audience, if only because would-be readers will be busy playing around with the bots. A deeper danger, not yet upon us but perhaps not far away, is that the bots will be able to effectively copy our best-known writers and creators.

One current common strategy is to give away a lot of writing, or images, for free on the web, and use the resulting publicity to build an audience for more commercial outputs, such as books and lectures and artworks. In the future, that may be asking for trouble, as the bots will copy you and in essence you will be training your competitors for free. It will work only if you can produce charisma and celebrity, two traits that will rise in importance.

The “old school” strategy of releasing limited editions, not available on the internet and not fully defined by their digital qualities, may increase in importance, as it will be harder for AI to copy such outputs.

The prior generation of information technology favored the introverts, whereas the new AI bots are more likely to favor the extroverts. You will need to be showing off all the time that you are more than “one of them.” Originality, including “in your face” originality, will be at a premium. If you are afraid to be such a “show off,” how is the world to know you are anything other than a bot with a human face?

Alternatively, many humans will run away from such competitive struggles altogether. Currently the bots are much better at writing than say becoming a master gardener, which also requires skills of physical execution and moving in open space. We might thus see a great blossoming of talent in the area of gardening, and other hard to copy inputs, if only to protect one’s reputation and IP from the bots.

Athletes, in the broad sense of that term, may thus rise in status. Sculpture and dance might gain on writing in cultural import and creativity. Counterintuitively, if you wanted our culture to become more real and visceral in terms of what commands audience attention and inspiration, perhaps the bots are exactly what you’ve been looking for.

How do geologists think?

From Dinwar, in the comments:

As for what it means to think like a geologist….it’s complicated. There definitely is a particular way of thinking unique to geologists. I’m convinced that it’s something you’re either born with or not; training just finishes what you started. Engineers and geologists think VERY differently, in nearly incompatible ways, which is fun because we work together all the time.

The main thing is, geologists think in terms of the context of deep time. We view everything from the perspective of millions of years, minimum. When a geologist looks at a stream they see the depositional zones, the erosional zones, the flood plane–and they are thinking both how the local geology affected it and how the stream will look in five million years. (As an aside, you get really strange looks when you discuss this with your eight-year-old son at a park.) And I do mean EVERYTHING. I remember drinking some loose-leaf tea once, adding the tea to the cup then the water, and realizing as the leaves settled that the high surface-area-to-volume ratio combined with cell damage from desiccation made them get water-logged very quickly, allowing for certain flood deposits to form. I’d always been curious about that.

Another thing to remember is that geologists by definition are polymaths. You can’t be a third-rate geologist unless you have a deep understanding of physics, chemistry, biology, anatomy, fluid dynamics, engineering, astronomy, and a host of other fields. Geology is what you get when those fields overlap. I learned as much about brachiopod anatomy from a structural geologist as I did from any paleontologist, and my minerology class started with “Here’s the nuclear physics of stellar evolution.” We’re expected to know drilling and surveying and cartography and…well, pretty much anything that could possibly affect dirt.

Ultimately, since we are dealing with historical sciences, we are detectives. We examine clues, make hypotheses, and look for evidence to support or refute them (for a fantastic discussion of this find the paper “Strong Inference”–that’s held as an ideal for geologic thinking). Like any scientist we look for subtle things, things that have a bearing on our particular field of study. I’m convinced, for example, that the soil in one area I work in has two distinct layers: a loose, fluffy depositional layer of clay, and a more firm layer of clay derived from the limestone bedrock dissolving. This is due to subtle variations in firmness, moisture content, color, whether or not limestone pieces are in the material, etc.–stuff that most people don’t notice. It’s no special ability on my part–my mother notices things about the weave of cloth that are invisible to me, because she makes the stuff. It’s all training. But the desire to look for it? That’s personality.

Field geologists are even worse–we do all that, only in conditions that would make any sane person run screaming. We’re expected to be athletes, MacGyver, scientists, managers, and Les Stroud all rolled into one. On bad days we add combat medic to the list. Hiking on a broken leg isn’t considered an unreasonable expectation (bear in mind I’m talking about the geologists–my safety manager would be VERY cranky to hear about someone doing that!). People who do this sort of thing routinely view the world in slightly different ways from most ordinary people. Most geologists go through a course called Field Camp, which is an introduction to field work. Walk into any geology department that has this and you can tell who’s gone through the class and who hasn’t.

Why are Jamaicans the fastest runners in the world?

That is one chapter in Orlando Patterson’s new and excellent The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament. One thing I like so much about this book is that it tries to answer actual questions you might have about Jamaica (astonishingly, hardly any other books have that aim, whether for Jamaica or for other countries). So what about this question and this puzzle?

Well, in terms of per capita Olympic medals, Jamaica is #1 in the world, doing 3.75 times better by that metric than Russia at #2. This is mostly because of running, not bobsled teams. Yet why is Jamaica as a nation so strong in running?

Patterson suggests it is not genetic predisposition, as neither Nigeria nor Brazil, both homes of large numbers of ethnically comparable individuals, have no real success in running competitions. Nor do Jamaicans, for that matter, do so well in most team sports, including those demanding extreme athleticism. Patterson also cites the work of researcher Yannis Pitsiladism, who collected DNA samples from top runners and did not find the expected correlations.

Patterson instead cites the interaction of a number of social factors behind the excellence of Jamaican running, including:

1. Preexisting role models.

2. The annual Inter-Scholastic Athletic Championship, also known as Champs, which provides a major boost to running excellence.

3. Proximity and cultural ties with the United States, which give athletically talented Jamaicans the chance to access better training and resources.

4. The Jamaican diet and a number of good public health programs, contributing to the strength of potential Jamaican runners (James C. Riley: “Between 1920 and 1950, Jamaicans added life expectancy at one of the most rapid paces attained in any country.”)

5. The low costs of running, and running practice, combined with the “combative individualism” of Jamaican culture, which pulls the most talented Jamaican athletes into individual rather than team sports. (That same culture is supposed to be responsible for dancehall battles and the like as well.)

Whether or not you agree, those are indeed answers. The book also considers “Why Has Jamaica Trailed Barbados on the Path to Sustained Growth?”, “Why is Democratic Jamaica so Violent?”, and a number of questions about poverty. Amazing! Those are indeed the questions I have about Jamaica, among others.

Recommended, you can pre-order here.

How I practice at what I do

Following up on my post a few days ago, about the value of deliberate practice for knowledge workers, a number of you asked me what form my practice takes. A few of you were skeptical, but it is long since established that practice improves both your writing and your memory, so surely it can do much more than that for your thinking. Here is a partial list of some of my intellectual practice strategies:

1. I write every day. I also write to relax.

2. Much of my writing time is devoted to laying out points of view which are not my own. I recommend this for most of you.

3. I do serious reading every day.

4. After a talk, Q&A session, podcast — whatever — I review what I thought were my weaker answers or interventions and think about how I could improve them. I rehearse in my mind what I should have said. Larry Summers does something similar.

5. I spent an enormous amount of time and energy trying to crack cultural codes. I view this as a comparative advantage, and one which few other people in my fields are trying to replicate. For one thing, it makes me useful in a wide variety of situations where I have little background knowledge. This also helps me invest in skills which will age relatively well, as I age. For me, this is perhaps the most importantly novel item on this list.

6. I listen often to highly complex music, partly because I enjoy it but also in the (silly?) hope that it will forestall mental laziness.

7. I have regular interactions with very smart people who will challenge me and be very willing to disagree, including “GMU lunch.”

8. Every day I ask myself “what did I learn today?”, a question I picked up from Amihai Glazer. I feel bad if I don’t have a clear answer, while recognizing the days without a clear answer are often the days where I am learning the most (at least in the equilibrium where I am asking myself this question).

9. One factor behind my choice of friends is what kind of approbational sway they will exercise over me. You should want to hang around people who are good influences, including on your mental abilities. Peer effects really are quite strong.

10. I watch very little television. And no drugs and no alcohol should go without saying.

11. In addition to being a “product” in its own right, I also consider doing Conversations with Tyler — with many of the very smartest people out there — to be a form of practice. It is a practice for speed, accuracy in understanding written writings, and the ability to crack the cultural codes of my guests.

12. I teach — a big one.

Physical exercise is a realm all of its own, and that is good for your mind too. For me it is basketball, tennis, exercise bike, sometimes light weights, swimming if I am at a decent hotel with a pool. My plan is to do more of this.

Here are a few things I don’t do:

Taking notes is a favorite with some people I know, though my penmanship and coordination and also typing are too problematic for that.

I also don’t review video or recordings of myself, for fear that will make me too self-conscious. For many people that is probably a good idea, however.

I don’t spend time trying to improve my memory, which is either very bad or very good, depending on the kind of problem facing me. (If I need to remember to do something, I require a visual cue, sometimes a pile on the floor, and that creates a bit of a mess. But it works — spatial organization is information!)

I’ve never practiced trying to type on a small screen, though probably I should.

I’ll close by repeating the end of my previous post:

Recently, one of my favorite questions to bug people with has been “What is it you do to train that is comparable to a pianist practicing scales?” If you don’t know the answer to that one, maybe you are doing something wrong or not doing enough. Or maybe you are (optimally?) not very ambitious?

Better training has brought big improvements to the quality of athletics and also chess, and many of those advances are quite recent — when is the intellectual world going to follow suit? When are you going to follow suit?

Height, size, and tennis

Five of the 16 men in the fourth round of singles at the United States Open are at least 6-5, and seven of the 16 women are at least 5-10…

The serve is the aspect in which undersized players most feel the height gap — they do not get to hit down on the ball and thus cannot generate the same power as taller players.

In earlier decades height was not nearly as important for tennis success. Yet:

Returning serve is one area in which shorter players tend to be better than the largest of their counterparts…

Flipkens said shorter players had to learn to analyze the game better, reading their opponent’s tosses to make the most of their return opportunities.

Austin said, “Anticipation is not an overt skill, but it is crucial to develop.”

Once the ball is in play, smaller players frequently rely on superior speed. “Everybody is taller than me,” the 5-1 Kurumi Nara said, “so I try to move well and more quickly than the other person.”

While bigger players are getting more agile, most still are not light on their feet. Low balls at the feet make them uncomfortable.

Glushko said taller players “don’t like the ball hit into the body,” and that applies to serves too.

Smaller players like Siegemund said the best tactic was to stand further back, allowing them to run down more balls — and to let the balls come down to a more manageable height. But to play defense and extend rallies, Seigemund said, smaller players must stay in top shape.

“All the players are fit, but we have to be fitter,” she said.

Some say the opposite approach may be more helpful. “The whole point of tennis is to rob your opponent of time,” Austin said. “You can do that with raw power or by hitting the ball early. Shorter players need to take the ball extra early.”

That is from Stuart Miller at the NYT. In addition to having some interest in tennis, I wonder to what extent this is a property of achievement in general. As the logic of meritocracy advances, and the pool of talent is searched more efficiently, perhaps individuals with a clear natural advantage — whether size, smarts, or something else — become a larger percentage of top achievers. Yet those wonderful “natural athletes” will have their weaknesses, just as Shaquille O’Neal had hands too large for the effective shooting of free throws. So a second but smaller tier opens up for individuals who have the smarts, versatility, and “training mentality” to fill in the gaps left open by the weaknesses of the most gifted. Who are the “taller” and “shorter” players in the economics profession? Politics? The world of tech? Are there any “short players” left in the top ranks of the world of chess? I don’t think so.

And maybe, for these reasons, late growth spurts are a source of competitive advantage?

*The Away Game: The Epic Search for Soccer’s Next Superstars*

I found this book by Sebastian Abbot very stimulating, though I wished for a more social-scientific treatment. The focus is on Africa, here is one bit on the more conceptual side:

But focusing on a young player’s technique still tells a scout relatively little about whether the kid will reach the top level, even when the observations are paired with physical measures of speed and agility. A study published in 2016 looked at the results from a battery of five tests conducted by the German soccer federation on over 20,000 of the top Under-12 players in the country. The tests measured speed, agility, dribbling, passing, and shooting. The researchers assessed the utility of the tests in determining how high the kids would progress once they reached the Under-16 to Under-19 level. The study found that players who scored in the 99th percentile or higher in the tests still only had a 6 percent chance of making the youth national team.

So what else might you look to?:

They assessed the game intelligence of players by freezing match footage at different moments and asking players to predict what would happen next or what decision a player on the field should make. Elite players were faster and more accurate in their ability to scan the field, pick up cues from an opponent’s position, and recognize, recall, and predict patterns of play.

And:

Researchers have found that the key ingredient is not how much formal practice or how many official games players had as kids, but how much pickup soccer they played in informal settings like the street or schoolyard.

The implications for economics study and speed chess are obvious. Finally:

Researchers found that athletes have a 25 percent larger attention window than nonathletes.

Is that true for successful CEOs as well? By the way, I hope to blog soon about why human talent is in so many endeavors the truly binding constraint.

This is an interesting Africa book, too.

Fatigued Physicians Make Mistakes and Harm Patients

Fatigued drivers cause accidents. In response to this obvious fact, we limit bus and taxi drivers to a maximum of 10 hours of driving after 8 consecutive hours off duty. Yet when it comes to physicians, the current standard is significant more lax; first-year residents are restricted to 16-hour shifts! That already is nuts. I often teach a night class, 7:20-10 pm and I always try to teach the more difficult material early because by 9pm I am not at the top of my game. Needless to say, medical residents are far more stressed and fatigued than teachers. Moreover, while first year residents can work up to 16 hours, second year residents can work up to 24 hours straight and even up to 30! Isn’t it amazing how one year of residency can teach physicians how to function without sleep?

The current standards, which strike me as absurdly low, are actually due to restrictions put in place in 2003 and 2011–restrictions which are now being lifted. The new plan is to allow longer hours for first year residents:

Rookie doctors can work up to 24 hours straight under new work limits taking effect this summer — a move supporters say will enhance training and foes maintain will do just the opposite.

A Chicago-based group that establishes work standards for U.S. medical school graduates has voted to eliminate a 16-hour cap for first-year residents. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education announced the move Friday as part of revisions that include reinstating the longer limit for rookies — the same maximum allowed for advanced residents.An 80-hour per week limit for residents at all levels remains in place under the new rules.

Studies have found that physicians who work longer hours are much more likely to get into auto accidents on the way home. Physicians and nurses who work longer hours also make more medical mistakes.

The main argument in favor of long hours is that the 2003 and 2011 restrictions do not seem to have greatly improved patient safety. That is surprising but the micro and experiential evidence that fatigue makes for mistakes is so strong that the lesson to be drawn isn’t that longer hours don’t lead to mistakes–the lesson is either that the restrictions were routinely ignored (as the National Academy of Science study found), that the studies done to date are misleading for a statistical or design reason or that there is another constraint in the system that needs to be examined. One possibility for another constraint is that handoffs of patients between physicians aren’t handled well. But that means that poor handoffs are killing as many people as fatigue!

In no other field do we tolerate error as much as we do in medical care. Why does the government regulate driving hours more than medical hours? It’s not just the government. It’s amazing that in a society where McDonald’s can be sued for making people fat that the tort system hasn’t shut down absurdly long residency hours (there have been a few cases). Medical care is a peculiar field (cue Robin Hanson).

Aside from Hanson-type factors, a key factor that explains what is going on is that residents are a huge profit source for the hospitals. Much like student athletes, residents are underpaid. As a result, hospitals want to use residents as much as possible so they lobby for longer hours even at the expense of patient safety.

Sunday assorted links

1. Mountains May Depart is an excellent Jia Zhangke movie, hat tip Scott Sumner. I also very much like The Innocents, still in some theaters around you.

2. Model this: Indian baby-tossing (NYT). And here is Luke Aikins-tossing, I note that a number of action movies with plunging heroes just became more plausible.

3. What people collect (NYT).

4. “There is no comprehensive data on U.S. Olympic athlete pay, but information collected by a nonprofit last year from 150 track and field athletes ranked in the top 10 in the country in their events found an average income of $16,553.” Link here. The coaches and bureaucrats typically make much more.

5. Is the “better camera” the main reason why we are all so worried? Not my view, but always happy to put contrasting opinions before you.

6. What a “left wing” British debate looks like. Don’t even click on or read that highly intelligent yet train wreck of a link, just return to my earlier claim “…the important European thinkers of the next generation will be religious, not left-wing and secular.”

Tradeoffs

From David Foster Wallace's 1995 essay, The String Theory:

… it's better for us not to know the kinds of sacrifices the professional-grade athlete has made to get so very good at one particular thing. Oh, we'll invoke lush cliches about the lonely heroism of Olympic athletes, the pain and analgesia of football, the early rising and hours of practice and restricted diets, the preflight celibacy, et cetera. But the actual facts of the sacrifices repel us when we see them: basketball geniuses who cannot read, sprinters who dope themselves, defensive tackles who shoot up with bovine hormones until they collapse or explode. We prefer not to consider closely the shockingly vapid and primitive comments uttered by athletes in postcontest interviews or to consider what impoverishments in one's mental life would allow people actually to think the way great athletes seem to think. Note the way "up close and personal" profiles of professional athletes strain so hard to find evidence of a rounded human life — outside interests and activities, values beyond the sport. We ignore what's obvious, that most of this straining is farce. It's farce because the realities of top-level athletics today require an early and total commitment to one area of excellence. An ascetic focus. A subsumption of almost all other features of human life to one chosen talent and pursuit. A consent to live in a world that, like a child's world, is very small.

Hat tip to Tim Carmody filling in at Kottke.

Should under-20s be allowed in the NBA?

It appears that Commissioner David Stern is pushing to ban under-20s from NBA play. And surprise, the player’s union — whose median member is older than 20 — is not screaming about this proposal. But what are the economics? If a team drafts an under-20 player, are there negative external costs placed on the rest of the league? I can see a few scenarios:

1. Drafting younger players makes it harder for bad teams to improve. The lower-ranked teams pick first, but now they are no longer assured of getting real value. The draft becomes more like a true lottery, which hurts the long-run competitive balance of the league. And if teen players do pan out in a few years time, they can become free agents and move to winning teams.

2. Drafting younger players forces teams to spend more on scouting to predict player quality. College ball in essence provides free training and free information.

3. Drafting younger players gives the league as a whole a bad reputation. Furthermore the overall quality of play is lower. Teams invest in future stars and future wins, not caring enough about the bricks they shoot up in the meantime. But hey, other people are watching, or at least we hope so.

4. Forcing young athletes to play in college induces college ball fans (blecch, I hate college basketball) to take greater interest in the NBA.

5. Young phenoms, such as LeBron James, now have more years in the league since they are drafted earlier. This boosts interest and attendance for everybody. If you think that the NBA is superstar-driven, arguably teams do not draft young enough.

6. Perhaps later drafting would produce more stars. Many players rush to the NBA and lose the chance to learn the game. They are overconfident, while a commons problem plagues the drafting teams. Waiting would make almost everyone better off, yet no single party can be induced to wait.

I’ll side with #5. I suspect that Stern and the player’s union are either a) making a simple mistake in the name of misguided moralism, or b) crafting some broader Faustian and Coasian bargain where Stern offers this as one chip.

Mind over Muscle or Where is Fatigue?

The old theory, taught to me in high school, is that muscles become fatigued when they run out of fuel/oxygen or they become suffused with lactic acid, an unpleasant byproduct of work. But if this is so, why do athletes almost always manage to go their fastest in the last mile of a race when their muscles should be closest to exhaustion? An article in New Scientist, (“Running on Empty,” by Rick Lovett, 20 March, 04, p.42-45, a copy is here) based on the work of Timothy Noakes and others, raises some more puzzles and offers a new theory.

If fatigue is based in the muscles then without more fuel, oxygen or less lactic acid you should not be able to improve performance. Yet, amphetamines and drugs like Ecstasy do allow athletes and clubbers to work and play harder (sometimes to dangerous effect). Measurements of the input factors also show that (absent unusual factors) fatigued muscles don’t in fact run out of critical factors.

The common sense response to these puzzles is that runners speed up in the last mile because they know it is the last mile and are willing to push themselves to their limits. Similarly, drugs fool the brain into thinking that the muscles are less fatigued than they are. If one thinks seriously about this common sense notion, as has Thomas Noakes, it provides a quite different view of fatigue than the old theory. The brain in this view is a central regulator that monitors the muscles and sends out messages of fatigue, quite possibly long before the muscles are truly spent as a sort of insurance policy. The central regulator theory doesn’t say that fuel and oxygen are unimportant only that the relation between fuel and fatigue is mediated by the brain.

The central regulator may have rational expectations. Experienced runners apparently report that the first mile of a 10k race is easier than the first mile of a 5k race. Makes no sense on the old theory but if you think about the central regulator meting out a fatigue budget in advance then everything becomes clear.

How then to improve performance? Try convincing yourself that you are running a 10k instead of a 5k (hypnosis may work). Also, Noakes suggests interval training, interspersed bouts of high intensity workouts with recovery breaks. The idea here is to the teach the central regulator that going faster won’t do you any harm.