Month: March 2006

Data Prizes

I suspect greater payoffs will come from more data than from more technique.

So said Alan Greenspan and I think he is right. Think of how much important work, for example, has been based on the Summers-Heston, Penn World Tables. Yet, most of the time the collectors of data toil in the fields unrecognized and unrewarded. When original data is collected it’s often hoarded – better to mine it for yourself than open up the commons. Now, that is a tragedy.

We ought to increase rewards to data collection. As a salutary example, which might be emulated by the AEA and others, Mike Kellerman points to the Dataset Award given by the APSA Comparative Politics section for "a publicly

available data set that has made an important contribution to the field of

comparative politics."

Department of !

Saturn moon spewing water vapor. Or so it seems…

Experimental economics vs. field economics

Uri Gneezy and John List write:

Recent discoveries in behavioral economics have led scholars to question the underpinnings of neoclassical economics. We use insights gained from one of the most influential lines of behavioral research — gift exchange — in an attempt to maximize worker effort in two quite distinct tasks: data entry for a university library and door-to-door fundraising for a research center. In support of the received literature, our field evidence suggests that worker effort in the first few hours on the job is considerably higher in the "gift" treatment than in the "non-gift treatment." After the initial few hours, however, no difference in outcomes is observed, and overall the gift treatment yielded inferior aggregate outcomes for the employer: with the same budget we would have logged more data for our library and raised more money for our research center by using the market-clearing wage rather than by trying to induce greater effort with a gift of higher wages.

In other words, people in the real world show behavior much like that of traditional economic agents. Here is the paper. Have I mentioned that John List is one of the most important young economists? He has jumped from a U. Wyoming Ph.d. to a U. Maryland job to the notoriously-stingy-to-tenure Department of Economics at the University of Chicago. If you want to see a tough skeptic about many commonly accepted research results, especially in the realm of economic experiments, read some of John’s other papers. John is developing more finely grained methods of discovering when we should believe laboratory experiments. Are you surprised he puts greater trust in market data?

Stay tuned for Opposite Day

JewishAtheist suggests Opposite Day:

I was thinking it might be fun to have an opposite day, where the atheists do their best to argue that theism is correct and the theists do their best to argue that atheism is correct. Perhaps some Jews can argue that Christianity is correct and vice versa. The point is to get you to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and see what the logic looks like from that side.

It’ll only work if you really try, though. You must resist mocking or parodying the position you’re supposed to be fighting for.

I’ll open up the comments, and let you suggest a topic where I should blog the opposite of my point of view. Three mentions wins it (the standard rule these days), and of course it has to be a topic where I might plausibly have a point of view. Nor can you force me into a repugnant or embarrassing position ("we should kill all members of group X,"), and so on.

I don’t want to have the wrong impression carved into Google forever, devoid of this context, so "my good friend Tyrone" will actually write the post. My father wanted to name me that, but my mom had the good sense to resist and so Tyler it was.

Interesting links

1. David Friedman has a novel coming out.

2. Here is another good reason to have sex.

3. Contracts for everything, a’ la Mary Blige.

4. Long compound German nouns.

5. Bird flu, standing on one foot, by EffectMeasure. Here is a good analysis of avian flu in cats.

6. How baseball statistics confuse the transient and the permanent, pointer from Robert Schwartz.

7. George Lucas: "I predict that by 2025 the average movie will cost only $15 million."

8. How to moderate a panel, pointer from Chris Masse.

1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die

If you are a completist, as am I, buying this new book — yes it really is called 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die — is a dangerous move. It has already induced me to purchase George Bataille’s Story of the Eye (not what I thought!), Robert Musil’s Young Törless, Thomas Pynchon’s supposedly underrated Vineland, and Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island, which I expect contains the key to the mysteries of Lost. The volume is excellent for browsing and seeing what came out in a particular year. Elsewhere on the book front, David Maruszek’s long-awaited Counting Heads has idea futures, frozen heads, and a compelling literary style. I can’t imagine how it could have a good ending, but I am not yet at the point where I care.

Drought Insurance

The NYTimes reports on an innovation in disaster aid, drought insurance taken out by relief agencies.

In a pilot project that could someday transform the world’s

approach to disaster emergencies, the World Food Program has taken out

an insurance policy that will pay it should Ethiopia’s notoriously

fickle rains fail this year…The policy, which costs $930,000, was devised to create

a new way of financing natural disaster aid. Instead of waiting for

drought to hit, and people to suffer, and then pursuing money from

donors to be able to respond, the World Food Program has crunched the

numbers from past droughts and taken out insurance on the income losses

that Ethiopian farmers would face should the rains fail…….If it works, the insurance will get emergency money flowing

faster, before the haunting images of dying babies reach television

sets. It would also shift the risk from farmers to financiers.

Insurance like this could even have benefits in the United States. Private firms, of course, often do buy disaster insurance but the United States government might want to do the same. Hurricane insurance, for example, bought by the US government could better spread the costs of disasters to the well-diversified. In theory, the government could duplicate any insurance program with a tax and spending program (give Bill Gates money now and tax him when the disaster occurs) but in practice it’s going to be much easier to commit to an insurance plan than to an equivalent tax and spend plan.

More generally, drought insurance on this scale is part of the New Financial Order. I refer to Robert Shiller’s work on using macro-markets to

offer large-scale insurance. A market in GDP futures, for example,

could be used to hedge against declines in GDP such as have occured in

Argentina, South Korea or the future United States (yes Tyler, it could happen!).

Markets in the income of professions as a whole, e.g. the the income of

dentists, could be used by dentists to hedge against the possibility of

a super anti-cavity sealant. See Entrepreneurial Economics for more on macro markets.

Thanks to Alex Wolman for the pointer and Robin Hanson for discussion.

Speculative claims about Australia

Why do some countries keep all their people in a small number of large cities?

A good example of the relationship between climate variability and human population size is provided by Australia. It is unique among the larger nations in consisting of either very small settlements or large cities, for the middle-sized towns that predominate elsewhere in the world are almost entirely absent. This is a consequence of the cycle of drought and flood that has characterized the land from first settlement.

Small regional population centers have survived because they can batten down the hatches and endure drought, and large cities have also survived because they are integrated into the global economy. The resource networks of towns, however, are smaller than the region affected by climate variability, making them vulnerable to swings in income. Typically, what happens is that, as a drought progresses, the farm machinery dealership and and automotive dealership close down…When the drought finally breaks, these businesses do not return…instead people travel to larger centers to buy what they need, and in time end up moving there.

The Australian example shows that climate variability has in fact encouraged the formation of cities: Today it is the most urbanized nation on Earth.

That is from Tim Flannery’s The Weather Makers: How Man is Changing the Climate and What It Means for the Earth. A few passages make me wince, such as the romanticization of 18th century Scottish highlanders, but mostly it is the best popular science book on its topic.

My IRT ("introspective regression techniques") support Flannery’s implicit prediction. Think about all that empty desert in Saudi Arabia, although I wonder why the rather wet Uppsala is so dull. Opinions? Do we see concentrated population in major cities where it is driest and where the weather is most variable? I don’t recall that Ades and Glaeser mention this factor, but surely it deserves more study.

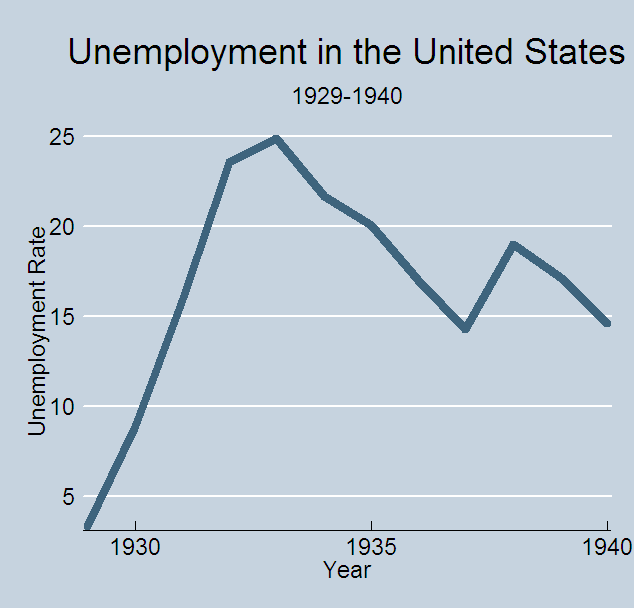

Krugman on Unemployment

Via Brad deLong is Paul Krugman’s introduction to the General Theory. Point Three in Krugman’s stripped down version is:

3. Government policies to increase demand, by contrast, can reduce unemployment quickly.

Well, that would certainly explain why unemployment recovered so quickly during the Great Depression. Or perhaps, despite the fact that "all it took to get the economy going again was a surprisingly narrow, technical fix," we just weren’t trying hard enough. See also Tyler’s comments.

Krugman’s introduction to Keynes’s General Theory

Krugman writes:

A reasonable man might well have concluded that capitalism had failed,

and that only…the nationalization of the means of production – could

restore economic sanity….Keynes argued that these failures had

surprisingly narrow, technical causes…

It is well-known that Keynes called for the socialization of investment and euthanasia of the rentier. Although I do not think he meant it by the 1940s (for background read this paper, or Keynes’s preface to the German-language edition of GT, which is Department of Uh-Oh material), it is odd for Krugman to ignore these passages and present Keynes as an outright enemy of government control or ownership of investment. Next, Krugman writes:

- Economies can and often do suffer from an overall lack of demand, which leads to involuntary unemployment

- The economy’s automatic tendency to correct shortfalls in demand, if it exists at all, operates slowly and painfully

- Government policies to increase demand, by contrast, can reduce unemployment quickly

- Sometimes increasing the money supply won’t be enough to persuade

the private sector to spend more, and government spending must step

into the breachTo a modern practitioner of economic policy, none of this – except,

possibly, the last point – sounds startling or even especially

controversial. But these ideas weren’t just radical when Keynes

proposed them; they were very nearly unthinkable. And the great

achievement of The General Theory was precisely to make them

thinkable….

Arthur Marget and other historians of thought have shown that such ideas were commonplace in pre-1936 macroeconomics, albeit not in Hayek and Robbins. The American tradition in particular pushed for activist fiscal policy, read for instance Jacob Viner. Several books document the popularity of this approach, again before the General Theory.

Jonathan Rauch on introverts

Here is a fascinating interview, much of which (not the gay part) describes me as well. In case you don’t already know it, here is Jonathan’s earlier piece on introversion.

Line-item vetoes won’t cut spending

Bush is asking for this authority, but it is unlikely to constrain spending. Read this (JSTOR) paper "Line-Item Veto: Where Is Thy Sting?". Excerpt: "Curiously, there exists little empirical support for the presumption that item-veto authority is important."

Or here is Robert Reischauer:

The crux of my message is that the item veto would have little effect on total spending and the deficit. I will buttress this conclusion by making three points. First, since the veto would apply only to discretionary spending, its potential usefulness in reducing the deficit or controlling spending is necessarily limited. Second, evidence from studies of the states’ use of the item veto indicates that it has not resulted in decreased spending; state governors have instead used it to shift states’ spending priorities. Third, a Presidential item veto would probably have little or no effect on overall discretionary spending, but it could substitute Presidential priorities for Congressional ones [TC: Hmm…].

Reischauer cites work by Douglas Holtz-Eakin:

Governors in 43 states [circa 1992] have the power to remove or reduce particular items that are enacted by state legislatures. The evidence from studies of the use of the item veto by the states, however, indicates no support for the assertion that it has been used to reduce state spending.

I have one simple model in mind: the legislature comes up with more individual pieces of pork in the first place. Can you think of others?

Taxation

Louis Kaplow is smart, here is his 119-page overview of the topic.

Should high schools compute class rank?

…something is missing from many applications: a class ranking, once a major component in admissions decisions…In

the cat-and-mouse maneuvering over admission to prestigious colleges

and universities, thousands of high schools have simply stopped

providing that information, concluding it could harm the chances of

their very good, but not best, students.

One college administrator notes:

"The less information a school gives you, the more whimsical our

decisions will be," he said. "And I don’t know why a school would do

that."

Here is the full article. As implied, colleges will still form rough expectations of what your rank would be. Given this response, we can see at least one reason why parents, and thus high schools, might prefer a fuzzy or ambiguous class ranking to a definite one.

Let us say your kid is smart but has a small chance of making it into a top school. At Yana’s high school (Woodson, in Fairfax) I’ve seen folders of students with 4.0 and 1600 SAT scores who did not get into Harvard or Yale. Getting into those places has elements of a crapshoot. You are gambling, with the odds against you, and a payoff varying only at some threshold level of success (i.e., getting in is what matters; if your kid doesn’t get in, it doesn’t matter how close he came.) Those are the classical conditions where the gambler prefers to take more risk. On the upside, your chance of getting in goes up and on the downside, the longer left-hand tail doesn’t hurt you.

Consider an analogy and assume I am trying to date Salma Hayek. Should I tell her what car I own (GeoPrizm, basically the same as a Toyota Corolla), or should I be vague? Now Salma is no dummy. If I am vague, she will not infer that I own a Rolls-Royce. But a GeoPrizm is clearly below her cut-off point, so with vagueness there is at least some chance she will not nix me right off the bat.

When I was a kid, a great resume meant you could go to Brown (and you only needed a Cadillac to date Raquel Welch). There was less reason to be ambiguous about class rank, as vagaries could hurt your chances in a very real way. You started off with something to lose, and being fifth in your class put you in pretty good stead.

Natasha tells me that many good law schools no longer provide class rank for their students. Is the same mechanism at work here, with many people chasing after a few hard-to-get plum jobs? Can you think of other examples where the principle of deliberately ambiguous rankings applies? Can this rationalize grade inflation?

Caught my eye

1. Amartya Sen reviews Bill Easterly.

2. Peter Leeson argues that anarchy is better for Somalia; most indicators of progress have gone up since the government fell. This is an excellent paper but I wonder how much "the end of war" drives the results, and is the current situation of warlords really "anarchy"?

3. Unchosen: The Hidden Lives of Hasidic Rebels, the title says it all. Some might find the text insulting ("…underneath the garb, Yossi was just a guy who liked Adam Sandler movies and country music…") but it offers a fascinating look at how small groups resist pressures for assimilation. Try also Paul Kriwaczek’s new Yiddish Civilization for a broader historical perspective; Born to Kvetch rounds out the recent trilogy.

4. Which countries are most proud of themselves? Venezuela does well, or poorly, depending on your point of view.

5. Here is a map of where the world’s ships are located (NB: this link doesn’t always work), hat tip to kottke.org.

6. Chris Masse’s yearly Prediction Market Awards.

7. Dave Schmidtz on when inequality matters. Here is Dave’s new book, Elements of Justice.

8. "Stichomancy," the art of fortune-telling through randomly-chosen book passages. Check out Caterina’s blog more generally. She links to this post on turning parking spaces into parks.

9. Netbanging: street gangs who slug it out over the Web.