Month: July 2006

The economics of procrastination?

I doubt if this is a selection effect:

It seems that adults in households that have digital video recorders

watch less TV than adults in the general population, according to a

recent analysis by Mediamark Research, an audience-measurement firm.

Here is the story. I, for one, usually read a library book sooner than a book I buy…

Macro book bleg

Most of my reading list consists of technical macro articles (I’ll post the new one when it is ready). But all students — even in Ph.d. macro — deserve a break. At least one of the readings should be literary and mostly fun, albeit stuffed with substance. Last year I used Paul Blustein’s And the Money Kept Rolling In, a study of Argentina.

I will use Blustein again but I might add another book. It should be readable, not too long, about something that matters, and of course have macroeconomic themes.

Please leave your suggestions in the comments.

Here is Brad DeLong’s book bleg; he wants to show his class that modern institutions are contingent rather than necessary. I want to inform them about current events or perhaps history.

Here are responses to Brad from CrookedTimber, none of which are very useful for a Ph.d. macro class. They are focused on economic anthropology.

Should prostitution be cartelized?

In the year 2000, the Dutch Ministry of Justice argued for a legal quota of foreign sex workers, because the Dutch prostitution market demands a variety of bodies (Dutting, 2001: 16). [Source here]

That is one of the most er…creative arguments for protectionism I have heard…

Second addendum: Here is a fascinating article about French policy.

Levitt’s reply to Lott

You’ll find it here; thanks to Tim Lambert for the pointer.

Eton College economics blog

Here it is, by Geoff Riley. Here is a post on advice for taking economics exams.

Did you know there is an econblog from Paul Romer’s Aplia?

New Economist offers yet more economics blogs you may not know about.

Why are people getting healthier?

The New York Times runs an excellent article. It is often forgotten how sick people used to be:

[Robert Fogel and colleagues] discovered that almost everyone of the Civil War generation was

plagued by life-sapping illnesses, suffering for decades. And these

were not some unusual subset of American men – 65 percent of the male

population ages 18 to 25 signed up to serve in the Union Army. “They

presumably thought they were fit enough to serve,” Dr. Fogel said.Even

teenagers were ill. Eighty percent of the male population ages 16 to 19

tried to sign up for the Union Army in 1861, but one out of six was

rejected because he was deemed disabled.

Heart disease rates and even cancer rates (per age cohort, I believe) were higher in times past.

The big question, of course, is why people are so much healthier (or for that matter smarter, see the Flynn Effect). It seems to be more than just better nutrition and sanitation. Scientists are focusing on time in the womb plus the first two years of life. Children born during the 1918 pandemic, for instance, fare much worse later in life in terms of health. The hypothesis is that the poor health of their mothers programmed them for later troubles.

The Netherlands is a land of giants. The people look quite healthy, despite high reported rates of disability. Average height is 6’1" or 6’2". And the Dutch are growing taller quickly. Why? Is it lots of Gouda cheese for Mommy? The mayonnaise on the french fries? Do small families play a role? The Protestants of the northern Netherlands are taller than the Catholics of the south. And if it is the cycling, are the teenagers in Davis, CA tall as well?

Markets in Everything: Butts

Producers often hire body doubles to save money on insurance. It

might cost a huge amount in risk coverage to have a high-priced star

dangle her leg off a ladder, for example. Instead, the production

company could pay a few hundred bucks for a much less valuable actor to

put her leg in harm’s way.When a movie needs a parts double for a "celebrity insert," the director or casting agent submits a notice to a set of casting services known as the "breakdowns." Talent agents

can supply doubles for very specific age ranges and body sizes, or for

skin tones like "peaches and cream," "warm vellum," and "golden

caramel." They can also send talent with special skills. For example, a

commercial director might want a hand model with "tabletop

skills"–someone who can pour a glass of beer at a constant rate or cut

a tomato into perfectly even slices.

That’s from Slate. I also liked this from Anita Hart the new bum of Slendertone:

They checked out my CV and saw that I had doubled for some of the greatest bums in Hollywood. I guess if I was good enough for Pammy and Liz, I was good enough for them. I sent them photos of my bum and the rest is history. It’s a real honour, lots of people have been the ‘faces’ of various products – no one has ever been a ‘bum’, so it really is a great privilege. If I continue to use their products, I hope to remain the bum of Slendertone for many more years.’

Thanks to Carl Close for the pointer.

Markets in everything, Japanese style

Safe for work, but deeply painful. I laughed so hard I cried. No matter what the text says, it is a Japanese comedy team; hat tip to Jason Kottke.

If you are going to completely ignore one MR post this year, it should be this one. Here is more of their stuff.

Who is to blame for the Doha collapse?

"Almost everyone" is not a bad answer. But perhaps you would like something more precise. Christian Bjørnskov has developed an index of blame, based on the degree of protectionism in a country’s negotiating position. He writes:

In total, a number of countries must share responsibility for the breakdown. Brazil and other Third World food exporters probably were too ambitious on behalf of the developed countries, India refused to accept more competition in its comparatively weak industries, and the US position remained opaque while the country for too long hid behind the protectionist positions of other member states. However, the bottom line is that the main culprit – the member bearing most of the responsibility – is the European Union. The problem continues to be that the official policy of the union is controlled by Southern European countries with strong agricultural lobbies – and the policy is therefore rather clearly dictated by Paris. French top politicians have throughout the negotiations ‘protected’ French farmers against cuts in tariffs or support measures – Jacques Chirac and Dominique de Villepin both went on air in national media to ensure their voters that France would veto any liberalization – which makes the country the Global Public Enemy Number One. Yet, another part of the story that needs to be told is that other EU members also made an indirect effort. The EU as a whole and traditionally liberalist countries such as the UK and Denmark in particular are all accomplices.

Colombia, a country with virtually no influence, had the highest pro-trade score. Bjørnskov does discuss the fact that the U.S. took an "easy" pro-trade position (it knew other countries would never agree), but I am not sure how this influenced his calculation of the index scores.

Thanks to Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard for the pointer.

How to insult a Dutchman

A (Dutch) study asked 192 young men to imagine being knocked off their feet by an assailant. Spaniards, Dutchman, and Germans were polled as to their likely response:

Insults from the Spaniards focused on references to animals and family members; for the Dutch it was references to diseases. The Germans preferred to cite body parts and functions…In Dutch to accuse someone of being infected with typhoid is a biting insult.

That is from The European Wall Street Journal, 18 July 2006, p.30, drawn originally from The Washington Post.

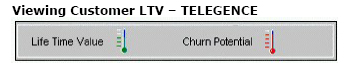

Price Discrimination Thermometer

When customers call Cingular threatening to switch to another firm or asking for discounts operators see a handy thermometer that tells them the life time value (LTV) of the customer to the company. The higher the meter reading the more discounts the operator is allowed to offer the customer. The Consumerist has the details including excerpts from company documents explaining the system.

Did tariffs boost 19th century U.S. economic growth?

It is a common view that the growth experience of the United States represents a strong case for the "infant industry" argument for protection. Bill Lazonick told us this repeatedly in my Harvard history of thought class. But is it true? Via Ben Muse, Douglas Irwin says no:

Were high import tariffs somehow related to the strong U.S. economic growth during the late nineteenth century? One paper investigates the multiple channels by which tariffs could have promoted growth during this period. I found that 1) late nineteenth century growth hinged more on population expansion and capital accumulation than on productivity growth; 2) tariffs may have discouraged capital accumulation by raising the price of imported capital goods; and 3) productivity growth was most rapid in non-traded sectors (such as utilities and services) whose performance was not directly related to the tariff.

The economics of marrying a foreign woman

One loyal MR reader has a 51-year-old friend who wishes to marry a younger [addendum: one source, who knows the man, says she need not be young…] foreign woman, possibly with a child. Yet he fears golddiggers. She seeks vicarious advice for him…

Discard facts of the day

In 2004 about 315 million working PCs were retired in North America…

In 2005 more than 100 million cell phones were discarded in the United States.

That is from Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America, by Giles Slade.

Jonathan Swift, a father of micro-credit

Swift was so, so, so smart and also hilariously funny. Recently I learned that he was one of the early progenitors of micro-credit. He started the Irish Loan Funds in the early 1700s to provide credit –without collateral — to the poor of Dublin. These loan funds started on a charitable basis but continued to grow and play a positive role in alleviating Irish poverty throughout the nineteenth century. Here is one account. Here is a broader piece on the history of microfinance. Here is a history of the Irish Loan Funds.

Here is Swift on reforming the coinage.