Month: October 2006

Incentives for Organ Donation

In an important editorial the Washington Post advocates giving points in the current organ allocation system to people who have previously signed their organ donor cards. I have long argued for such a system (see Entrepreneurial Economics and here) and am an advisor to Lifesharers an organization that is implementing a similar system privately.

The decision to pledge organs could be linked to the chance of

receiving one: People who check the box on the driver’s-license

application when they are healthy would, if they later fell sick, get

extra points in the system used to assign their position on the

transplant waiting list (other factors include how long you have waited

and how well an available organ would match your blood type and immune

system).

Thanks to Dave Undis for the pointer.

Economics books everyone should know

Here is one list, taken from a poll of Carnegie-Mellon faculty. For most readers I would scrap Becker, Heilbroner, and Duffie; of course many other books could be added. "Paul Shiller" should be "Robert." The pointer is from Craig Newmark.

Addendum: CrookedTimber readers offer their suggestions.

Markets in everything, canine edition

Ice cream maker Good Humor and pet food producer Pedigree have announced plans to produce ice cream sandwiches for dogs.

Apparently this is not a stupid pet snack. The companies said they needed a special formula for the dairy treats, as many dogs are lactose intolerant and cannot easily digest regular ice cream.

Here is the story, and thanks to Robert Stewart for the pointer.

Should we diversify our charitable giving?

Citing Steve Landsburg, Tim Harford argues:

Someone with $100 to give away and a world full of worthy causes should

choose the worthiest and write the check. We don’t. Instead, we give $5

for a LiveStrong bracelet, pledge $25 to Save the Children, another $25

to AIDS research, and so on. But $25 is not going to find a cure for

AIDS. Either it’s the best cause and deserves the entire $100, or it’s

not and some other cause does. The scattershot approach simply proves

that we’re more interested in feeling good than doing good.Many people are unconvinced by this argument–which I owe to Steven Landsburg–because

they are used to diversifying their financial investments (a bit of

Google stock and a bit of Exxon, too) and varying their choices

(vanilla ice cream AND bananas). But those instincts are selfish: They

are not intended to benefit both Google and Exxon, nor both the

ice-cream company and the banana growers. With charity, the logic is

different, and a truly selfless donor would bite the bullet and put his

entire donation behind one cause. That we find that so hard to imagine

is just one more indication of how hard it is for us to think ourselves

into a truly selfless view of the world.

We can think of charitable projects, at least in ex ante terms, as aligned along a continuum of expected returns. The highest-return project is just a wee bit better than the runner-up candidate. In that setting, it is hard, as always, to evaluate the efficiency consequences of differing distributions of wealth. But in a Rawlsian sense — what would a poor person want if he did not know which group he would end up assigned to? — the poor would prefer that any particular gift is diversified. Even if the dollar rate of return falls by a small amount, the insurance value of that giving rises.

Keep in mind that a single donation is itself supporting a bundle of projects, not a single giving opportunity. (What would a truly specialized donation look like?)

I agree with Harford’s point in a different regard. The fixed costs of processing a donation are relatively high, if only because the charity will send further letters asking for more money. For that reason it may be better to focus our giving on a single charity.

Why is Medicine so Primitive?

The practice of modern medicine is surprisingly primitive. My doctor only recently started to provide printed prescriptions instead of the usual scrawl. Incorrectly filled prescriptions can be serious and computer printed prescriptions are an obvious response yet even today only one in four physicians use some form of electronic health records and only one in ten really use electronic records to follow a patient’s entire history. My credit card company knows far more about my shopping history than my physician knows about my medical history.

Medicine is primitive in another way. The number of treatment regimes supported only by tradition and authority is very high. Here’s a recent example:

For the past 30 years or so, doctors have routinely given pregnant

women intravenous infusions of magnesium sulfate to halt contractions

that can lead to premature labor.…[a] team reviewed 23 clinical trials worldwide involving 2,000 women who

had received the drug to quell contractions. They found that it did not

reduce preterm labor and that more babies died when their mothers took

the drug than in a control group where the mothers had not been given

it.…Grimes and Nanda estimate that about 120,000 American women receive mag

sulfate each year for premature contractions, and they say some

evidence suggests it may be associated with 1,900 to 4,800 fetal deaths

annually in the United States.

This would be a shocker except for the fact that stories like this are common – by some accounts a majority of medical procedures are not supported by serious scientific evidence. Indeed, what are we to make of a profession where evidence-based medicine is only a recent and still far from accepted movement?

Why is medicine so primitive? One reason is that medicine is the largest area of the economy still dominated by artisanal production. I will be blunt: We need assembly line medicine, medicine that is routinized, marked and measured. As I have argued before I would much prefer to be diagnosed by a computerized expert system than by a physician. The HMOs, Kaiser in particular, have done good work on measuring the effectiveness of different procedures but much more needs to be done to bring medicine into the twentieth century let alone the twenty first.

Sweden fact of the day

By the late 1990s the Wallenbergs controlled some 40% of the value of the companies listed on the Swedish stock exchange.

Read more here.

The behavioral economics of pain

The two main lessons, as I read this paper, are a) pain is less bad when the sufferer can see the endpoint, and b) pain is less bad when the sufferer feels in control to some measure.

The concluding discussion of "happiness economics" is on the mark:

…my personal reflections are only in partial agreement with the literature on well being (see also Levav 2002). In terms of agreement with adaptation, I find myself to be relatively happy in day-to-day life – beyond the level predicted (by others as well as by myself) for someone with this type of injury. Mostly, this relative happiness can be attributed to the human flexibility of finding activities and outlets that can be experienced and finding in these, fulfillment, interest, and satisfaction. For example, I found a profession that provides me with a wide-ranging flexibility in my daily life, reducing the adverse effects of my limitations on my ability. Being able to find happiness in new ways and to adjust one’s dreams and aspirations to a new direction is clearly an important human ability that muffles the hardship of wrong turns in life circumstances. It is possible that individuals who are injured at later stages of their lives, when they are more set in terms of their goals, have a more difficult time adjusting to such life-changing events.

However, these reflections also point to substantial disagreements with the current literature on well-being. For example, there is no way that I can convince myself that I am as happy as I would have been without the injury. There is not a day in which I do not feel pain, or realize the disadvantages in my situation. Despite this daily awareness, if I had participated in a study on well-being and had been asked to rate my daily happiness on a scale from 0 (not at all happy) to 100 (extremely happy), I would have probably provided a high number, probably as high as I would have given if I had not had this injury. Yet, such high ratings of daily happiness would have been high only relative to the top of my privately defined scale, which has been adjusted downward to accommodate the new circumstances and possibilities (Grice 1975). Thus, while it is possible to show that ratings of happiness are not influenced much based on large life events, it is not clear that this measure reflects similar affective states.

As a mental experiment, imagine yourself in the following situation. How you would rate your overall life satisfaction a few years after you had sustained a serious injury. How would your ratings reflect the impact of these new circumstances? Now imagine that you had a choice to make whether you would want this injury. Imagine further that you were asked how much you would have paid not to have this injury. I propose that in such cases, the ratings of overall satisfaction would not be substantially influenced by the injury, while the choice and willingness to pay would be – and to a very large degree. Thus, while I believe that there is some adaptation and adjustment to new life circumstances, I also believe that the extent to which such adjustments can be seen as reflecting true adaptation (such as in the physiological sense of adaptation to light for example) is overstated. Happiness can be found in many places, and individuals cannot always predict their ability to do so. Yet, this should not undermine our understanding of horrific life events, or reduce our effort to eliminate them.

Here are Dan’s papers, and here. Here are Dan’s riddles.

Lancet

Left-wing bloggers, such as CrookedTimber, Brad DeLong, and Tim Lambert, are supporting the claim of about 600,000 extra deaths in Iraq. Jane Galt (scroll down for a few posts) and Steve Sailer raise some concerns.

I am a bit skeptical, but in any case the sheer number of deaths is being overdebated. Steve Sailer notes: "The violent death toll in the third year of the

war is more than triple what it was in the first year." That to me is

the more telling estimate.

A very high deaths total, taken alone, suggests (but does not prove) that the Iraqis were ready to start killing each other in great numbers the minute Saddam went away. The stronger that propensity, the less contingent it was upon the U.S. invasion, and the more likely it would have happened anyway, sooner or later. In that scenario the war greatly accelerated deaths. But short of giving Iraq an eternal dictator, that genie was already in the bottle.

If the deaths are low at first but rising over time, it is more likely that a peaceful transition might have been possible, either through better postwar planning or by leaving Saddam in power and letting Iraqi events take some other course. That could make Bush policies look worse, not better. Tim Lambert, in one post, hints that the rate of change of deaths is an important variable but he does not develop this idea.

We all know that the political world judges Iraq by the absolute badness of what is going on (which means Bush critics find a higher number to fit their priors), but that is an incorrect standard. We should judge the marginal product of U.S. action, relative to what else could have happened. (North Korea, and the UN response, will give us one data point from another setting.) In that latter and more accurate notion of a cost-benefit test, U.S. actions probably appear worst when deaths are rising over time, and hitting very high levels in the future.

Of course the rate of change of deaths is not exactly the proper variable. Ideally we would like some measure of the contingency of eventual total deaths, relative to policy. I am not sure what other proxies for that we might have.

Addendum: Let me put my comment up here on the front page: "Many of you are misreading the post by focusing only on the first case

of "bottled up killing," which is presented as only one of two

scenarios. Reread that if deaths are rising over time and possibly

contingent — and yes I do say this is the relevant and uncontroversial

fact — this suggests a very negative evaluation of Bush policies."

I don’t want to take the bait on why I am skeptical, the whole argument is that possible skepticism doesn’t have that much import once we consider the broader context of rising deaths and the possible contingency of those deaths.

Why no patent or copyright for new food recipes?

A loyal MR reader writes in:

Why do we have IPRs for literature, the arts and music but not for food dishes? Of course, I’m not talking about a copyright on the Ham & Cheese sandwich, I’m talking about innovative new dishes…I’m not arguing that we SHOULD have IPRs for food, just wondering what the big difference is (if any) between the culinary arts and other arts…I realize it would be difficult to enforce such rights at mom & pop type places…but it would be possible to enforce those rights at big name places and large chains.

Food relies so much on execution, or at the national chain level on marketing, that the mere circulation of a recipe does not much diminish the competitive advantage of the creative chef. Try buying a fancy cookbook by a celebrity chef and see how well the food turns out. (In contrast, an MP3 file is a pretty good substitute for a CD.) Most chefs view their cookbooks as augmenting the value of the "restaurant experience" they provide, not diminishing it. Furthermore industry norms, and the work of food critics, will give innovating chefs the proper reputational credit. It is not worth the litigation and vagueness of standards that recipe patents would involve.

Here is a recent article on recipe copyright.

Here is an academic paper on how norm-based copyright governs the current use of recipes. French chefs will ostracize "club members" who copy innovative recipes outright. Now the fashion industry wants IP protection as well.

Assorted

1. Mark Perry’s new economics blog.

2. Give oil money to the Iraqis? Maybe not.

3. Norway message in a bottle reaches New Zealand.

4. Topalov blunders a rook in sudden death play, Kramnik wins the title.

5. Robin Hanson on betting markets in CEO tenure.

Economist wins Nobel Peace Prize

The winner is Muhammad Yunus, economist (!) and founder of the micro-credit movement, along with his Grameen Bank. Here is the story. Here is his Wikipedia entry. Here is my New York Times column on micro-credit. Here is the best piece on what we know about micro-credit. Here is Yunus’s book on micro-credit, which also serves as a memoir and autobiography. It is a captivating and well-written story.

This is a wonderful choice. The funny thing is, they never would have considered this guy for the Economics prize.

I would write more, but a) read my column, and b) the Topalov-Kramnik sudden death speed chess tiebreakers are being played this morning, watch them live here. Susan Polgar offers running commentary here.

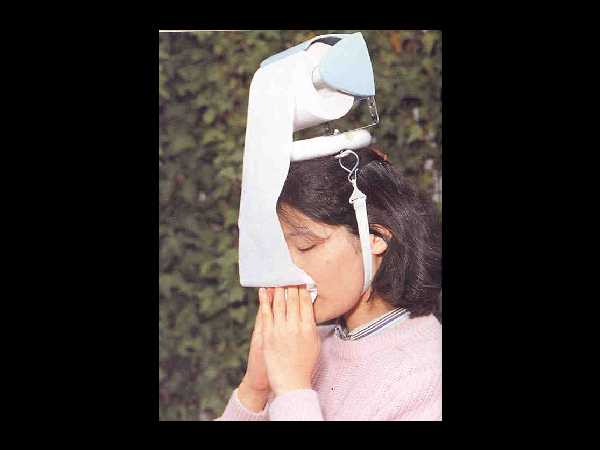

Markets in everything, Japanese edition

Here are seven more.

Why hasn’t South Africa done well?

Dani Rodrik reports:

South Africa has undergone a remarkable transformation since its

democratic transition in 1994, but economic growth and employment

generation have been disappointing. Most worryingly, unemployment is

currently among the highest in the world. While the proximate cause of

high unemployment is that prevailing wages levels are too high, the

deeper cause lies elsewhere, and is intimately connected to the

inability of the South African to generate much growth momentum in the

past decade. High unemployment and low growth are both ultimately the

result of the shrinkage of the non-mineral tradable sector since the

early 1990s. The weakness in particular of export-oriented

manufacturing has deprived South Africa from growth opportunities as

well as from job creation at the relatively low end of the skill

distribution. Econometric analysis identifies the decline in the

relative profitability of manufacturing in the 1990s as the most

important contributor to the lack of vitality in that sector.

Here is a non-gated version of the paper. The bottom line is that South Africa is de-industrializing.

Overlooked fiction from recent years

Slate.com polled several bloggers and booksellers, scroll down to find my pick. You are welcome to leave your ideas in the comments…

If you read only one book by Orhan Pamuk

The White Castle is short, fun, and Calvinoesque. Not his best book but an excellent introduction and guaranteed to please. Snow is deep, political, and captures the nuances of modern Turkey; it is my personal favorite. The New Life isn’t read often enough; ideally it requires not only a knowledge of Dante, but also a knowledge of how Dante appropriated Islamic theological writings for his own ends. My Name is Red is a complex detective story, beloved by many, often considered his best, but for me it is a little fluffy behind the machinations. The Black Book is the one to read last, once you know the others. Istanbul: Memories and the City is a non-fictional memoir and a knock-out.