Month: July 2008

Where should you cast your vote?

Jonah Berger, Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Wharton School of

Business, conducted a terrific study where he demonstrates that where people vote affects how they vote.

Essentially, people whose voting booth is located in a church are more

likely to put more weight into social issues, people voting in fire

houses care more about safety, and people voting in a school tend to

put more weight on things like education.

Admittedly there is a problem here of isolating causation. Perhaps you go to the polls whose location you know, and if you have kids you know how to find the school, if you are religious you know how to find the church, and so on.

Auren Hoffman, whom I will see next week in Quebec City, concludes:

Your gut might be much better at telling you what not to do than giving

you good direction on what to do. If your gut tells you something is

wrong with someone, than you probably do not want to entrust your kid

with her. But a positive gut-check often does little good (at least for

me).

In Defense of Short-Selling

Props to Dean Baker.

Short-selling can play a very important role in the market. If

informed investors recognize that a stock is over-valued they perform a

valuable service by selling it short and pushing down its stock price.

This can both deprive the company of capital and be a signal to other

actors in the market that the company might not be as healthy as is

generally believed.The economy would have benefited enormously if large numbers of

traders had shorted Fannie and Freddie 4 years ago when they were

buying up hundreds of billions of mortgages issued to buyers who bought

homes at bubble-inflated prices. This would have stopped the bubble

years ago. Similarly, we could have prevented the financial chaos at

Merrill Lynch, Citigroup, Bear Stearns and the rest, if traders had

recognized their financial shenanigans and aggressively shorted their

stock. In the same vein, heavy shorting by informed investors could

have prevented the boom and bust of the tech bubble.The decision to intervene against short-selling is completely

inconsistent with the belief in the wisdom of the markets. Of course

short-sellers can be wrong and depress stock prices more than is

justified by fundamentals, but so what? The government doesn’t

intervene when it thinks investors have exaggerated the true value of a

stock. The public has no more reason to fear under-valued stock prices

than over-valued stock prices. This one-sided intervention by SEC is

hard to justify on any grounds.

Assorted links

1. Fifty outstanding translations, via Bookslut.

2. The cost of being Batman, via www.geekpress.com

3. More on the file-sharing controversy

4. The new "Big Mac" index, so to speak

Risk Free No Longer

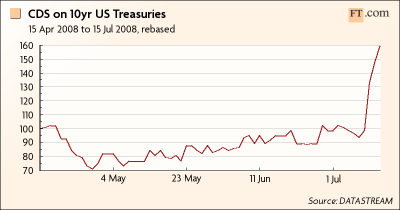

Wow, we usually think about U.S. bonds as being the "risk-free" asset but with a credit default swap you can buy insurance on a US default and the price of such insurance is way up.

The change in price is a shock but to put things in perspective do note that the price for insuring US debt is now higher than for German debt but similar to that for Japanese and British debt. We are still far from Argentinian levels.

Hat tip to at, in the comments to my post on the peso problem.

Spend More Today

In Nudge Thaler and Sunstein motivate their Save More Tomorrow plan with the following unfortunate illustration:

Consider, for example, the case of Tony Snow, the former White House press secretary, who resigned at age fifty-two in 2007 to return to the private sector. He said his motivation for leaving was financial. "I ran out of money," he told reporters…Before serving as press secretary, Snow worked a much more lucrative gig as a Fox News Channel anchor. But he arrived at the White House not having learned Retirement 101 lessons. "Snow conceded: ‘As a matter of fact, I was even too dopey to get in on a 401(k).’

Sadly, Snow’s choices now look optimal. Ok, I know that may be in poor taste but let’s try to rescue this observation with some theorizing. Are we more likely to commit the error of saving too much or too little?

There are people who don’t save much because they have very low incomes, their behavior does not seem to be in error, especially when we take into consideration the various welfare programs that will cover people in their old age.

So let’s focus on people with moderate to high incomes. Thaler and Sunstein say that we are more likely to make errors when the benefits are upfront and the costs are delayed. Eating too much chocolate being a classic example. Ok, that suggests we may save too little.

T. and S. also argue that the less frequent a decision the more likely are errors. Frequency, however, cuts both ways – we only die once – so that’s a wash.

Over confidence and in particular the idea that we are special and will live a long life suggests the error is saving too much. Note that we also tend to think that our partner will be alive as well. My wife once asked me whether we were saving enough for "our" retirement. "Sure," I said, "don’t forget one of us will probably die before the other and I’m not saving for your future husband." "Why," she replied with a sigh, "can’t economists be more human?"

Availability bias probably also suggests we save too much – we see people who saved too little in the street but the ones who saved too much are dead and gone.

In theory, optimal saving equalizes the marginal utility of income across one’s lifetime – some programs like Kotlikoff’s ESPlanner attempt to calculate such an eqi-marginal utility flow and Kotlikoff’s finding is that a large fraction of Americans, some 40%, are saving too much. Kotlikoff’s program takes into account that we may need less wealth when we are old and retired (e.g. less transportation for work related reasons) but not that the marginal utility of wealth may be lower when we are old. (e.g. Money’s not so valuable if you don’t need it to or can’t use it to attract a mate.) Thus over-saving may be even more common than Kotlikoff suggests.

I do not know which error is more prevalent but if we are to be neither spendthrift nor miser we need to recognize both types of error.

How can the price of oil move so much in one day?

Over the two previous days oil fell $10.50 a barrel. By definition this is driven by news about supply and demand but has so much news come out so quickly?

Here are two ways to think about the mechanisms at work. First, some producers could supply more but they figure that China will be buying more tomorrow so maybe it is better to wait. If they see a signal that future global demand will be lower, they are less likely to let oil sit in the ground. In other words the market develops the expectation — true or not — that oil supply will rise more rapidly than had been thought (or "decline less rapidly" may in some cases be a more accurate phrase but the net direction of the effect is the same). Lower expected demand is thus paired with greater expected supply and that tends to make price volatile. Higher expected demand is paired with lower expected supply in similar fashion. noting in either case that you can make lots of different assumptions about the relative timing of the expected changes.

Second, any new information leads to more trading and to more trading at different ranges of price and quantity. This trading reveals more information about the elasticities of market supply and demand curves and that information in turn feeds back into the market price. In a nutshell, some initial price and quantity movements lead to further price and quantity movements.

Neither of these phenomenon are correctly called "bubbles" but neither do they fit the story where the price of oil is determined by fundamentals alone. "Expectations" is a central word here, noting that only time will tell whether or not the expectations are rooted in reality or not.

Do not buy art on cruise ships

In case you did not know. Here is one example of a fool:

It was only after Mr. Maldonado landed back in California that he did

some research on his purchases. Including the buyer’s premium, he had

paid $24,265 for a 1964 “Clown” print by Picasso. He found that

Sotheby’s had sold the exact same print (also numbered 132 of 200) in

London for about $6,150 in 2004.

Of course the corruption and foolishness runs deeper than the article lets on. If you shop for contemporary prints in entirely "reputable" Georgetown galleries, they will charge about twice the going auction rate for the prints. They might tell you that the prints are "hard to find" when in fact usually they are not. A good New York dealer, used to dealing with well-informed customers, might charge only 10-15 percent above auction (full price including buyer’s premium). The bottom line is that you should never spend more than $1500 on art unless you know at least roughly what it is worth at auction. One of life’s good rules of thumb.

Larry Summers on the agencies

He always had a talent for the bottom line. On the mortgage agencies he writes:

What went wrong? The illusion that the companies were doing virtuous

work made it impossible to build a political case for serious

regulation. When there were social failures the companies always blamed

their need to perform for the shareholders. When there were business

failures it was always the result of their social obligations.

Government budget discipline was not appropriate because it was always

emphasized that they were "private companies.” But market discipline

was nearly nonexistent given the general perception — now validated —

that their debt was government backed. Little wonder with gains

privatized and losses socialized that the enterprises have gambled

their way into financial catastrophe.I wonder how general the lesson here might be. My fear is fairly

general. Inherent in the multiple objectives urged for creative

capitalists is a loss of accountability with respect to performance.

The sense that the mission is virtuous is always a great club for

beating down skeptics. When institutions have special responsibilities

it is necessary that they be supported in competition to the detriment

of market efficiency.It is hard in this world to do well. It is hard to do good. When I

hear a claim that an institution is going to do both, I reach for my

wallet. You should too.

Here is more. Larry Summers was my professor for Macro II and every lecture was a joy. "Lecture" isn’t even the right word, it was more like turning on a faucet.

Short essays by Angus Deaton

Find them here, hat tip to Tim Harford.

I want you to ponder sentences about vengeance

Females, older people, working people, people who live in high-crime

areas of their country and people who are at the bottom 50% of their

country’s income distribution are more vengeful.

Here’s a more traditional result:

The findings suggest that vengeful feelings of people are subdued as a

country develops economically and becomes more stable politically and

socially and that both country characteristics and personal attributes

are important determinants of vengeance.

Here is the paper, here is the author’s home page.

Robin Hanson on the belief in religion and government

A stunning hypothesis from the latest Journal of Personality and Social Psychology:

High

levels of support often observed for governmental and religious systems

can be explained, in part, as a means of coping with the threat posed

by chronically or situationally fluctuating levels of perceived

personal control. Three experiments demonstrated a causal relation

between lowered perceptions of personal control and … increased

beliefs in the existence of a controlling God and defense of the

overarching socio-political system. A 4th experiment showed … a

challenge to the usefulness of external systems of control led to

increased illusory perceptions of personal control. … A

cross-national data set demonstrated that lower levels of personal

control are associated with higher support for governmental control.It

seems we hope a stronger and more benevolent God or State will protect

us when feel less able to protect ourselves. I’d guess similar effects

hold for medicine and media – we believe in doc effectiveness more when

we fear out of control of our health, and we believe in media accuracy

more when we rely more on their info to protect us. Can we find data

on which beliefs tend to be more biased: confidence in authorities when

we feel out of control, or less confidence in authorities when we feel

more in control?

I would say "read the whole thing" except that is the whole thing. Here is evidence from California that voters are more likely to prefer conservative candidates (not exactly what the above study is testing) when economic times are good.

What should government do to stimulate the economy?

Let’s see what New York Times readers think. Right now there’s only one comment and it’s not totally encouraging:

Triple the minimum wage.

That would bring it more in line with

increases in efficiency and rates in the late 70s. People make more,

they spend more. All the money is just tied up in investments now, like

bonds in Fannie and Freddie.

But surely the quality of the answers will improve as the day passes, no? No? No?

Help!

Should donors give to students rather than schools?

Jonathan Bydlak seeks to match donors directly with students, rather than matching donors to universities. Here is his group. One advantage of the idea is greater competition:

…the current system ties the amount of accessible financial

aid to the schools that students attend, giving schools with more

resources a distinct advantage…students accepted to a Princeton or Harvard face virtually no

quality vs. price trade-off.What this means for higher education as a whole is that the

current financial aid system, whereby alumni and other prominent donors

contribute to schools, rather than individuals, reinforces the

perceived status of those schools that are considered “top-tier.”While demand for high quality higher education continues to increase

massively,

the supply of top-tier higher education has not changed much

at all (one need only look at the lack of variability in the U.S. News

rankings for proof of this point). And as any Econ 101 student can

tell you, when demand far outstrips supply, costs are inevitably pushed

upward.

I like the idea but fear that institutions of higher learning can offer donors greater perks than can intermediaries that match donors to students. Might it be possible to, say, offer donors the chance to support students through the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with the Met taking a lower cut than Harvard does, yet still handing out donor perks?

Why might Israel attack Iran

According to this line of thinking, which has adherents…focusing on the tactical questions surrounding such an operation — how much of Iran’s nuclear program can Israel destroy? how many years can a bombing campaign set the program back? — is a mistake. The main goal of a hit would not be to destroy the program completely, but rather to awaken the international community from its slumber and force it to finally engineer a solution to the crisis…any attack on Iran’s reactors — as long as it is not perceived as a military failure — can serve as a means of "stirring the pot" of international geopolitics. Israel, in other words, wouldn’t be resorting to military action because it is convinced that diplomacy by the international community cannot stop Iran; it would be resorting to military action because only diplomacy by the international community can stop Iran.

That is Shmuel Rosner in the 30 July The New Republic. Personally I do not think that Israel will attack Iran, but since I had never heard this argument before I thought I would pass it on.

Assorted links

1. Megan Non-McArdle is blogging again, at rhubarbpie. Here is her post on which are the lovable women.

2. Markets in everything: a restaurant with a menu for dogs (but how can they afford it?)

3. Star Wars according to a three year old, a short YouTube video via Yana