Month: July 2010

The culture that is Russia fact of the day

The Ministry of Emergency Situations reported that 77 people drowned in Russia on Saturday and Sunday, adding to the grim total of more than 400 people so far in July and 1,244 people in June. Most of them, if past reports on Russia’s extraordinary numbers of drownings are any guide, were drunk, and the numbers were not sharply out of line with those of previous years – Russians typically drown at a rate more than five times that of Americans.

…the sultry blast was almost unbearable for Muscovites. Work in the capital slowed to a crawl, and residents crept from sweltering apartments to lounge in the parks and on riverbanks, stripping off clothes and taking ill-advised dips in the Moscow River.

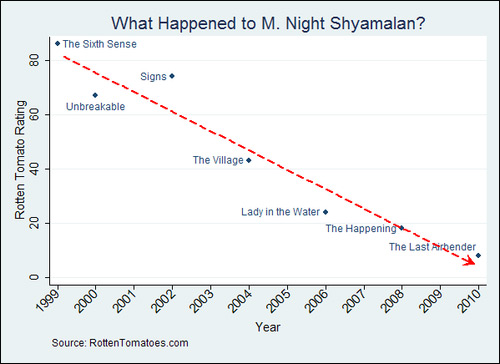

What Happened to M. Night Shyamalan?

ICE Trust and CDS swaps

Created in its current form in 2009, this institution has become the central clearinghouse for CDS swaps. Just about everyone has favored the clearinghouse reform, but the more I read the more I find the course of affairs to be slightly unsettling:

1. The major banks play a strong role in ownership and governance of ICE Trust. There's nothing necessarily wrong with that, but does the clearinghouse have the incentive to check excess risk-taking behavior and demand adequate collateral? (The clearinghouse does seem to have optimal incentives when it comes to netting.) And might the clearinghouse might help banks "game" the new regulatory system? Keep in mind these same banks were not disciplining each other adequately as creditors, so why should they adopt a more socially optimal set of dealings through a clearinghouse?

2. As of the spring, ICE had a market capitalization of $9 billion; relative to the size of the outstanding exposures in the CDS market, is that a lot or a little? Remember that the A.I.G. bailout had an upfront cost of about $70 billion. Is it possible that the Fed still ends up holding the bag here? In fairness, note that both clearinghouse regulation, and CFTC/SEC regulation of the clearinghouse, may help prevent such a recurrence. Better netting and position limits may go a long way.

3. "Robert Litan, an economist at the Brookings Institution, says he worries that the broker-dealer members could use ICE Trust to “blunt the competition” from competing clearinghouses and will keep it a dealers-only club with high margin requirements. ICE Trust currently requires all clearing members to have at least $5 billion in capital to join.

Another concern is ICE Trust’s 11-member board of directors, of which five members are either ICE managers or are broker-dealer representatives. Litan says ICE Trust should have a wholly independent board of directors. In a recent interview with the Center, Litan said he hopes that regulators, under the financial reform bill will begin to push for the governance issues he has championed, Litan said." Source here.

4. "Darrell Duffie, a professor of finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and a member of the Financial Advisory Roundtable of the New York Federal Reserve, supports using a clearinghouse for credit default swaps. But he cautions that segregating the CDS market from the rest of the $500 trillion market for over-the-counter (off-exchange) derivatives runs counter to the risk-reducing purpose of using such an exchange." Same source as #2. The underlying research is here.

5. ICE's parent institution is located in the Cayman Islands. It seems this is for tax reasons, is fully legal, and it has been approved by the Fed. MR readers will have different views on this set-up, I expect, but you can see why financial critics might feel leery. It also has been suggested that the Cayman Islands locale helps banks repatriate profits untaxed; it is not clear (to me at least) whether the new FinReg bill changes this arrangement. Is this all a reason why the clearing isn't going through the better-established Chicago Mercantile Exchange?

6. The Fed was regulating ICE but in the new FinReg bill the SEC and CFTC have joint authority over the institution, with overall the CFTC having the lead role for what is currently, or has been, OTC derivatives. Standards for regulation do not yet appear well fleshed out, here is one set of comments.

Here is a good article by Lucy Komisar on ICE. I don't want to sound too alarmist, I don't want to go back to non-clearinghouse days, and I wish to stress that these matters are hard to judge. Still, what I'm reading isn't reassuring me as much as I would have liked.

Circa 1961, or, the more things change…

At the August FOMC meeting, Young reported on a lengthy discussion at OECD of West Germany's persistent surplus. The economic solution required either German inflation, additional revaluation of the mark, or deflation elsewhere. The German delegation rejected inflation and revaluation…

That is from Allan Meltzer's History of the Federal Reserve, volume 2, book 1, 1951-1969.

Krugman on Cowen and Germany

Let's consider Krugman's three main points:

1. This was not an effort at fiscal stimulus; it was a supply policy, not a demand policy. The German government wasn’t trying to pump up demand — it was trying to rebuild East German infrastructure to raise the region’s productivity.

2. The West German economy was not suffering from high unemployment — on the contrary, it was running hot, and the Bundesbank feared inflation.

3. The zero lower bound was not a concern. In fact, the Bundesbank was in the process of raising rates to head off inflation risks — the discount rate went from 4 percent in early 1989 to 8.75 percent in the summer of 1992. In part, this rate rise was a deliberate effort to choke off the additional demand created by spending on East Germany, to such an extent that the German mix of deficit spending and tight money is widely blamed for the European exchange rate crises of 1992-1993.

On #1, policymakers may intend all kinds of results, including a new skat table for Onkel Mathias and bananas for Brandenburg. The scenario nonetheless saw a big boost in debt, spending, and aggregate demand, and in a setting with unemployed resources. That makes it one test case, even if the primary motive was the unification of Germany and not stimulus per se.

On #2, you willl find data on German unemployment rates here, for each half of the country and consolidated. In the West there is unemployment before unification, a big boost in employment during the first two years of unification, and then much higher unemployment.

Let's track those rates, starting in 1989: 7.9, 7.2, 6.2, 6.4, 8.0, 9.0, 9.1 (1995), 9.9, 10.8, 10.3, etc.

You can read those numbers two ways. First, stimulus worked until they lost heart, or "it boosts the economy in the short run but it postpones adjustment problems and in the medium run you end up with a poor and sluggish private sector job market." I was making the simpler historical-explanatory point that, no matter how you slice and dice the data, the poor outcome in absolute terms explains why the Germans are not so impressed by ideas of debt, spending and aggregate demand. And if stimulus proponents keep on losing heart at the critical moments, the citizenry is still right to be skeptical.

The real story requires a look at the tottering East German labor market as well. At the immediate moment of unification, unemployment/underemployment for the consolidated Germany are higher than the above numbers behind the link indicate; read for instance these comments and also here.

The strongest criticism of the example is not one that Krugman considers. If you had access to a more finely calibrated employment index, reflecting the gross underemployment of DDR workers, with continually collapsing jobs, there is at least some chance the true data series might show more effectiveness for fiscal policy than the published data, or the West German mood at the time, would indicate.

#3, like #1, is a distraction. The zero bound might — in some frameworks — make fiscal policy necessary rather than monetary policy. But the zero bound is not required to drive the main arguments that fiscal policy is effective with unemployed resources. So historical examples with a non-zero bound and ineffective fiscal policy do count against fiscal policy.

As an aside, you can find some RBC and cash constraint models where fiscal policy is more effective at the zero bound, but a) I think these papers are deeply flawed, b) the liquidity constraints in those models do much of the work and those constraints held anyway for parts of East Germany, and c) Krugman and others are advocating fiscal policy for a wide variety of economies, not all of which are at the zero bound, even if they have constrained monetary policy for other reasons, such as Ireland.

On #3, Krugman is correct that the Bundesbank actions hurt the German economy (though keep in mind, at the time of tightening in 1992 the rate of German price inflation was five percent and it stayed at 4.4 percent the year after). This implies that tight monetary and loose fiscal policy, taken together, won't work. I endorse that conclusion. It also shows that the monetary authority moves last, which is exactly the point made by fiscal policy critics such as Scott Sumner. Stressing that point does no favors to the argument for fiscal expansion, quite the contrary. Krugman is eager to slap down the historical example but he is losing track of the broader principle he cites to do so.

Overall the pro-ramp-up-the-spending fiscal policy advocates are keener to produce examples which don't count than examples which do count. The positive arsenal is pretty weak, consisting mainly of World War II, an experience which cannot be repeated or replicated.

Krugman also directs his attention at a secondary point in the argument, taking up a single paragraph in the column. He doesn't touch the main point: Germany cut off fiscal stimulus early and focused on the real economy and they're doing fine. Even if you think this prosperity is at the expense of others (and I don't), the pro-ramp-up-the-spending-stimulus view suggests that Germany itself should be ailing, yet it isn't. Here are further good comments on that topic.

On the main point of the column, you can find some good criticisms from Ryan Avent, though I would stress it is exports not stimulus that led the German recovery and that Germany is not obviously due for a spill.

Assorted links

Number of Birds Killed

Number of birds killed by the BP oil spill: at least 2,188 and counting.

Number of birds killed by wind farms: 10,000-40,000 annually.

Number of birds killed by cars: 80 million annually.

Number of birds killed by cats: Hundreds of millions to 1 billion annually.

Don't worry there is some good news.

Number of birds killed by fisheries: tens to hundreds of thousands annually (fortunately for the birds, some of these fisheries are now shut down).

Zero marginal product workers

Matt Yglesias suggests the notion is implausible, but I am surprised to read those words. Keep in mind, we have had a recovery in output, but not in employment. That means a smaller number of laborers are working, but we are producing as much as before. As a simple first cut, how should we measure the marginal product of those now laid-off workers? I would start with the number zero. If a restored level of output wouldn't count as evidence for the zero marginal product hypothesis, what would? If I ran a business, fired ten people, and output didn't go down, might I start by asking whether those people produced anything useful?

It is true that the ceteris are not paribus, But the observed changes if anything favor the hypothesis of zero marginal product. There has been no major technological breakthrough in the meantime. If anything, there has been bad monetary policy and a dose of regulatory uncertainty. And yet again we can produce just as much without those workers. Think of "labor hoarding" yet without…the hoarding.

You might cite oligopoly models and argue that the workers can produce something, but firms won't hire them because they don't want to expand output, due to lack of demand. That doesn't seem to explain that output has recovered and that profits are high. And since there is plenty of corporate cash, it is hard to claim that liquidity constraints are preventing the reemployment of those workers.

There is another striking fact about the recession, namely that unemployment is quite low for highly educated workers but about sixteen percent for the less educated workers with no high school degree. (When it comes to income groups, the lowest decile has an unemployment rate of over thirty percent, while it is three percent for the highest decile; I'm not sure of the time horizon for that income measure.) This is consistent with the zero marginal product hypothesis, and yet few analysts ask whether their preferred explanation for unemployment addresses this pattern.

Garett Jones suggests that many unemployed workers are potentially productive, but that businesses do not, at this moment, want to invest in future productive improvements. The workers only appear to have zero marginal product, because their marginal product lies in future returns not current returns. I see this hypothesis as part of the picture, although I am not sure it explains why current unemployment is so much higher among the unskilled. Is unskilled labor the fundamental capability-builder for the future? I'm not so sure.

It's also interesting to look at the composition of the long-term unemployed (not the same as the composition of all the unemployed, of course). Older workers with a college education are quite stuck, conditional on their being unemployed. And in this group, more education predicts a longer spell of unemployment. Is this ongoing "recalculation," optimal search theory, or is the roulette wheel simply coming up zero each time it is spun for these workers? Maybe a bit of each. If you want, call some of it age discrimination and relabel the idea "perceived zero marginal product."

In general, which hypotheses predict lots more short-term unemployment among the less educated, but among the long-term unemployed, a disproportionately high degree of older, more educated people? This stylized fact seems to point toward search and recalculation ideas, with some zero marginal products tossed in. Do aggregate demand theories yield that same data-matching prediction? I don't see it, at least not without being paired with a theory of concomitant real shocks.

Nothing in the zero marginal product hypothesis requires that these marginal products be zero forever. As the entire economy expands more rapidly (when will that happen?), the value of even a low quality worker can quickly become much higher. If you are opening up a new building, suddenly you really need that extra janitor and he is indeed more productive at the new margin.

Some people identify the zero marginal product hypothesis with the "hopeless dregs of the earth" description, but the two are not necessarily the same. Complementarity, combined with some fixed initial factors, can yield zero or near-zero marginal products of labor. (You'll see the phrase "excess capacity" used in this context, though that matches the oligopoly hypothesis more closely.) The "dregs of the earth" view is pessimistic, but the complementarity version of the zero marginal product idea can be quite optimistic, predicting a very rapid recovery in the labor market, once the interactions turn positive.

The "dregs" and the "complementarities" views also have different policy recommendations. The dregs view implies either hopelessness or a lot of fundamental retraining or ongoing assistance, while the complementarity view leads one to ask how we might mobilize positive complementarities (rather than leaving orphaned factors of production) more quickly. Perhaps there are some fixed factors, such as managerial oversight, and entrepreneurs do not want to strain those fixed factors too hard. How can we make such fixed factors more replicable or more flexible?

Addendum: Arnold Kling comments.

Why do we like adventure stories with guides?

Robin Hanson asks:

I’ve been sick, so watched tv more than usual. Watching Journey to the Center of the Earth, I noticed yet again how folks seem to like adventure stories and games to come with guides. People prefer main characters to follow a trail of clues via a map or book written by someone who has passed before, or at least to follow the advice of a wise old person.

Dante of course provides another example, as does Sibyl and Aeneas. And Robin's conclusion?:

This has a big lesson for those who like to think of their real life as a grand adventure: relative to fiction, real grand adventures tend to have fewer guides, and more randomness in success. Real adventurers must accept huge throws of the dice; even if you do most everything right, most likely some other lucky punk will get most of the praise.

If you want life paths that quickly and reliably reveal your skills, like leveling up in video games, you want artificial worlds like schools, sporting leagues, and corporate fast tracks. You might call such lives adventures, but really they pretty much the opposite. If you insist instead on adventuring for real, achieving things of real and large consequence against great real obstacles, well then learn to see the glorious nobility of those who try well yet fail.

Assorted links

1. NYT covers Hamburg's HafenCity.

2. More, please.

3. Katja on cryonics and selfishness.

4. Massachusetts health care update.

5. Women's role in Holocaust may exceed old notions.

6. "Just hand over the cash," another good article by Drake Bennett.

What Germany knows about debt

Here is my latest NYT column, excerpt:

Far from embracing this social democratic model, American Keynesians have criticized it for relying too heavily on exports and not enough on spending and debt. Yet it is not just the decline in the euro‘s value that supports the German resurgence.

Most of the other euro-zone economies are not having comparable success because they did not make the appropriate investments and reforms. Moreover, the euro is still stronger than its average value since 2001, which suggests that the recent German success is not attributable only to a falling currency.

In any case, the Germans are exporting much quality machinery and engineering (not just glitzy autos), which can help other nations recover. It is an odd state of affairs when the relatively productive nations are asked to change successful policies because of an economic downturn.

I would add a few points:

1. I am not sure why the American left so near-unanimously lines up behind Keynesian recommendations these days. (Jeff Sachs is an exception in this regard.) There are other social democratic models for running a government, including that of Germany, and yet a kind of American "can do" spirit pervades our approach to fiscal policy, for better or worse. Commentators make various criticisms of Paul Krugman, but putting the normative aside I find it striking what an American thinker he is, including in his book The Conscience of a Liberal. Someone should write a nice (and non-normative) essay on this point, putting Krugman in proper historical context.

2. You sometimes hear it said: "Not every nation can run a surplus," or "Can every nation export its way to recovery?" Reword the latter question as "Can every indiviidual trade his way to a higher level of income?" and try answering it again. Productivity-driven exporting really does matter, whether for the individual or the nation. It stabilizes the entire global economy,

3. There really is a supply-side multipler, and a sustainble one at that.

4. The phrase "fiscal austerity" can be misleading. Contrary to the second paragraph here, even most of the "austerity advocates" think that the major economies should be running massive fiscal deficits at this point. (And Germany had a short experiment with a more aggressive stimulus during the immediate aftermath of the crisis.) They just don't think it works for those deficits to run even higher.

5. The EU is an even less likely candidate for a liquidity trap than is the United States. That said, how to distribute and implement additional money supply increases would be a serious political problem for the EU. Simply buying up low-quality government bonds would work fine in economic terms, but worsen problems of moral hazard, perceived fairness, and so on. This problem should receive more attention.

Markets in Everything: A Puzzle

“Shared social responsibility” as a path to greater profit?

At a theme park, Gneezy conducted a massive study of over 113,000 people who had to choose whether to buy a photo of themselves on a roller coaster. They were given one of four pricing plans. Under the basic one, when they were asked to pay a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo, only 0.5% of them did so.

When they could pay what they wanted, sales skyrocketed and 8.4% took a photo, almost 17 times more than before. But on average, the tight-fisted customers paid a measly $0.92 for the photo, which barely covered the cost of printing and actively selling one. That’s not the best business model – the company proves itself to be generous, it’s products sell like (free) hot-cakes, but its profit margins take a big hit. You could argue that Radiohead experienced the same thing – their album was a hit but customers paid relatively little for it.

When Gneezy told customers that half of the $12.95 price tag would go to charity, only 0.57% riders bought a photo – a pathetic increase over the standard price plan. This is akin to the practices of “corporate social responsibility” that many companies practice, where they try to demonstrate a sense of social consciousness. But financially, this approach had minimal benefits. It led to more sales, but once you take away the amount given to charity, the sound of hollow coffers came ringing out. You see the same thing on eBay. If people say that 10% of their earnings go to charity, their items only sell for around 2% more.

But when customers could pay what they wanted in the knowledge that half of that would go to charity, sales and profits went through the roof. Around 4.5% of the customers asked for a photo (up 9 times from the standard price plan), and on average, each one paid $5.33 for the privilege. Even after taking away the charitable donations, that still left Gneezy with a decent profit.

The full article is here and I thank Michelle Dawson for the pointer.

Assorted links

1. Arthur Marget archive, on-line, lots there.

3. The board game that is German, by Tim Harford.

4. The culture that is Sweden, with good photos.

5. Via Kottke, this article isn't just about tennis.

Robot Parking

In the first DARPA Grand Challenge for driverless vehicles in 2004 not a single team came close to finishing the course. Later this year a driverless car built by a team from Stanford will race up Pike's Peak at speeds up to 90 mph. Amazing. And from the same team, I would pay for a car with this type of automated parking.