Month: February 2012

A message for all our readers in the United Kingdom

From Scott Sumner, but endorsed by me in full:

Take the current situation in the UK. If I’m not mistaken, the British political system is different from that in America. British governments are basically elected dictatorships, with no checks and balances. Even though the Bank of England is independent, the government can give it whatever mandate it likes. If I’m right then both fiscal and monetary policy are technically under the control of the Cameron government.

So I read the UK austerity critics as saying:

“Because you guys are too stupid to raise your inflation target to 3%, or to switch over to NGDP targeting, fiscal austerity will fail. We believe the solution is not to be less stupid about monetary policy, but rather to run up every larger public debts.”

Is that right? Is that what critics are doing?

Some will argue that my views are naive, that Cameron would be savagely attacked for a desperate attempt to print money as a way of overcoming the failures of his coalition government. Yes, but by whom? Would this criticism come from Ed Balls? Perhaps, but in that case he would essentially be saying:

“It’s outrageous that the Cameron government is trying to use monetary stimulus to raise inflation from 2% to 3%, whereas they should be using fiscal stimulus to raise inflation from 2% to 3%.”

I’m sorry to have to repeat this over and over again, but what 99% of pundits on both sides of the Atlantic are treating as a debate about “stimulus” and “austerity” is actually a debate about stupidity. I’m not saying the pundits are stupid (Krugman certainly understands what I’m saying) but rather they are addressing their audience as if the audience was stupid.

Don’t talk down to Cameron and Osborne! Don’t say “austerity will fail.” Say “austerity will work, but only if the BOE becomes much more aggressive, otherwise it will fail.” That sort of advice would be USEFUL. Instead we are getting a bunch of pundits getting ego boosts because they can say “I told you so.”

Scream it from the rooftops!

*The Failure of Judges and the Rise of Regulators*

That is the new book by Andrei Shleifer, and it collects his major and very important writings on regulation and law and economics, many with notable co-authors. Some of these papers have been discussed previously on MarginalRevolution. If you wish to own those papers, this is your book.

Questions that are rarely asked

From Arnold Kling (and the graph is from Karl Smith):

I challenge any supporter of the sticky-wage story (Bryan? Scott?) to write a 500-word essay explaining how this graph does not contradict their view. If employment fluctuations consisted of movements along an aggregate labor demand schedule, then employment should be at an all-time high right now.

My view is “sticky nominal wages for some, negative AD shock, ongoing stagnation and thus low job creation, and the progress we have is in some sectors immense but typically labor-saving rather than job-creating, all topped off with a liquidity shock-induced revelation that two percent of the previous work force was ZMP.” (Try screaming that from the rooftops.) I read the above graph as consistent with that mixed and moderate view. As Arnold notes, it’s harder to square with an AD-only view. If I wanted to push back a bit on Arnold’s take, and save some room for AD stories, I would cite the “Apple Fact of the Day,” and also note that stock prices have not responded nearly as well as have measured corporate profits. Still, we economists are not taking this graph seriously enough.

Addendum: Arnold Kling responds to responses.

Assorted links

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit

The skills necessary to ride a bike are multifaceted, complex and not at all obvious or even easily explicable to the conscious mind. Once you learn, however, you never forget–that is the power of habit. Without the power of habit, we would be lost. Once a routine is programmed into system one (to use Kahneman’s terminology) we can accomplish great skills with astonishing ease. Our conscious mind, our system two, is not nearly fast enough or accurate enough to handle even what seems like a relatively simple task such as hitting a golf ball–which is why sports stars must learn to turn off system two, to practice “the art of not thinking,” in order to succeed.

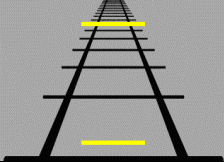

Habits, however, can easily lead one into error. In the picture at right, which yellow line is longer? System one tells us that the l ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

You never forget how to ride a bike. You also never forget how to eat, drink, or gamble–that is, you never forget the cues and rewards that boot up your behavioral routine, the habit loop. The habit loop is great when we need to reverse out of the driveway in the morning; cue the routine and let the zombie-within take over–we don’t even have to think about it–and we are out of the driveway in a flash. It’s not so great when we don’t want to eat the cookie on the counter–the cookie is seen, the routine is cued and the zombie-within gobbles it up–we don’t even have to think about it–oh sure, sometimes system two protests but heh what’s one cookie? And who is to say, maybe the line at the top is longer, it sure looks that way. Yum.

System two is at a distinct disadvantage and never more so when system one is backed by billions of dollars in advertising and research designed to encourage system one and armor it against the competition, skeptical system two. Yes, a company can make money selling rope to system two, but system one is the big spender.

Habits can never truly be broken but if one can recognize the cues and substitute different rewards to produce new routines, bad habits can be replaced with other, hopefully better habits. It’s habits all the way down but we have some choice about which habits bear the ego.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, about which I am riffing off here, is all about habits and how they play out in the lives of people, organizations and cultures. I most enjoyed the opening and closing sections on the psychology of habits which can be read as a kind of user’s manual for managing your system one. The Power of Habit, following the Gladwellian style, also includes sections on the habits of corporations and groups (hello lucrative speaking gigs) some of these lost the main theme for me but the stories about Alcoa, Starbucks and the Civil Rights movement were still very good.

Duhigg is an excellent writer (he is the co-author of the recent investigative article on Apple, manufacturing and China that received so much attention) It will also not have escaped the reader’s attention that if a book about habits isn’t a great read then the author doesn’t know his material. Duhigg knows his material. The Power of Habit was hard to put down.

Austerity as a substitute for trust

Here is a common view, not incorrect as far as it goes:

Struggling euro-zone economies like Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy cannot cut their way back to growth. Demanding rigid austerity from them as the price of European support has lengthened and deepened their recessions. It has made their debts harder, not easier, to pay off.

And here is a useful Paul Krugman post on austerity, perhaps the best single (brief) statement of his views on European austerity. Three observations:

1. I have yet to see a numerical analysis of European fiscal austerity which adjusts for a) falling ngdp, b) the collapse of their banking systems, c) and the collapse of M3 and money markets in some of these regions, noting that in Italy there are partial (very recent) signs of a money market turnaround. The blame gets pinned on the fiscal austerity.

2. I have yet to see a numerical analysis of European fiscal austerity which considers the prospect of later catch-up growth. This can make the costs of austerity much smaller, though of course from discount rates and habit formation there is still a cost.

3. Ideally it really would be better to say “Italy, I trust you to cut spending later, after your economy has recovered.” This cross-national trust is not present, least of all with Greece but also elsewhere. What is the best available policy in the absence of this trust, knowing that the periphery nations have to send some kind of credible signal to the wealthier nations of the North, in return for ongoing aid?

You can think of those three points as the “frontier reasons” why not all economists agree on European austerity. There are indeed some “dY/dG denialists,” but there are too many attacks on them and not enough explorations of the real issues.

Ironically, postponing austerity is most likely to succeed when there is lots of trust in a country (and in fact whether or not that trust is deserved). You can imagine the Swedes agreeing to themselves “we’ll cut spending three years from now” but the Greeks not, not without external constraint. Thus, writers who unmask the depravity of the American polity, and who polarize opinion, are oddly enough doing harm to the anti-austerity point of view.

You will find an alternative perspective on intellectual strategy here.

Assorted links

Books in my pile, real or virtual

1. The Economists’ Voice: Top Economists Take On Today’s Problems, edited by Stiglitz, Edlin, and DeLong, useful excerpts from the journal.

2. Noam Scheiber, The Escape Artists: How Obama’s Team Fumbled the Recovery. I enjoyed reading this book very much, though I am not the one to judge its account of “inside baseball.” There is plenty on Geithner and Summers. Here is Warsh on Scheiber on Summers.

3. Matthew D. Adler, Well-Being and Fair Distribution: Beyond Cost-Benefit Analysis. A detailed examination and defense of social welfare functions, which I have not read.

4. Tyler Cowen, Crie sua Própria Economia, in Brazilian, reviews and the like are here.

5. Alan Beattie, illustrious FT correspondent, Who’s in Charge Here?: How Governments are Failing the World Economy, eBook only, due out in March.

Why is there a shortage of talent in IT sectors and the like?

There have been some good posts on this lately, for instance asking why the wage simply doesn’t clear the market, why don’t firms train more workers, and so on (my apologies as I have lost track of those posts, so no links). The excellent Isaac Sorkin emails me with a link to this paper, Superstars and Mediocrities: Market Failures in the Discovery of Talent (pdf), by Marko Terviö, here is the abstract:

A basic problem facing most labor markets is that workers can neither commit to long-term wage contracts nor can they self fi nance the costs of production. I study the effects of these imperfections when talent is industry-specifi c, it can only be revealed on the job, and once learned becomes public information. I show that fi rms bid excessively for the pool of incumbent workers at the expense of trying out new talent. The workforce is then plagued with an unfavorable selection of individuals: there are too many mediocre workers, whose talent is not high enough to justify them crowding out novice workers with lower expected talent but with more upside potential. The result is an inefficiently low level of output coupled with higher wages for known high talents. This problem is most severe where information about talent is initially very imprecise and the complementary costs of production are high. I argue that high incomes in professions such as entertainment, management, and entrepreneurship, may be explained by the nature of the talent revelation process, rather than by an underlying scarcity of talent.

This result relates also to J.C.’s query about talent sorting, the signaling model of education, CEO pay, and many other results under recent discussion. If it matters to you, this paper was published in the Review of Economic Studies. I’m not sure that a theorist would consider this a “theory paper” but to me it is, and it is one of the most interesting theory papers I have seen in years.

Why doesn’t the right-wing favor looser monetary policy?

Reading Scott’s post induced me to write down these few points. I have noticed that right-wing public intellectuals are skeptical of more expansionary monetary policy for a few reasons:

1. There is a widespread belief that inflation helped cause the initial mess (not to mention centuries of other macroeconomic problems, plus the problems from the 1970s, plus the collapse of Zimbabwe), and that therefore inflation cannot be part of a preferred solution. It feels like a move in the wrong direction, and like an affiliation with ideas that are dangerous. I recall being fourteen years of age, being lectured about Andrew Dickson White’s work on assignats in Revolutionary France, and being bored because I already had heard the story.

2. There is a widespread belief that we have beat a lot of problems by “getting tough” with them. Reagan got tough with the Soviet Union, soon enough we need to get tough with government spending, and perhaps therefore we also need to be “tough on inflation.” The “turning on the spigot” metaphor feels like a move in the wrong direction. Tough guys turn off spigots.

3. There is a widespread belief that central bank discretion always will be abused (by no means is this view totally implausible). “Expansionary” monetary policy feels “more discretionary” than does “tight” monetary policy. Run those two words through your mind: “expansionary,” and “tight.” Which one sounds and feels more like “discretion”? To ask such a question is to answer it.

Within these frameworks of beliefs, expansionary monetary policy just doesn’t feel right. Yet I still agree with the arguments of Scott (and others) that it would have been the right thing to do.

What are the costs of signaling at a macro level?

There is a new paper from Ricardo Perez Truglia, from Harvard, on this topic. It strikes me as quite speculative, but nonetheless a step forward in addressing a very difficult question and adding some structure to the analysis of a very difficult problem. Here are his conclusions:

The goal of the paper is to provide a quantitative idea of the practical importance of conspicuous consumption. We estimated a signaling model using nationally representative data on consumption in the US, which we then use to estimate welfare implications and perform counterfactual analysis. We found that the market value of NMGs [TC: non market goods, as result from the signal] is non-negligible: for each dollar spent in clothing and cars the average household gets around 35 cents of net bene ts from NMGs. However, the large value of NMGs does not imply that the losses from the positional externality are also large. The results suggest that richer household would still consume relatively more of the NMG even in absence of NMGs, so the cost of the signal that they send is not very high. As a result, the signaling equilibrium attains almost 90% of the full potential bene ts from the NMGs, which is very e fficient. The unattained benefi ts, $32 per household per month, can serve as an intuitive upper bound to the bene fits that can be gained through economic policy, such as a tax on observable goods aimed at correcting the positional externality.

A related point is that if utility functions evolve so that people enjoy the very act of sending the signal, that too will lower the associated deadweight loss from signaling.

Here is the author’s home page.

Assorted links

2. Markets in everything, honey trap edition, or should they call it something else?

3. Do hedge fund returns have lower volatility?

4. The still-underrated Dylan Matthews covers MMT, graphic here.

5. Remarkable Swedish rescue, but of what?

Test-tube hamburger is on its way

The world’s first test-tube hamburger, created in a Dutch laboratory by growing muscle fibres from bovine stem cells, will be ready to grill in October.

“I am planning to ask Heston Blumenthal [the celebrity chef] to cook it,” Mark Post, leader of the artificial meat project at Maastricht University, said at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Vancouver.

The story is here. Both Alex and I have blogged about comparable (but less successful) projects in the past. Here is a longer article on the same development.

The most interesting man in the world?

At 9, he settled a dispute with a pistol. At 13, he lit out for the Amazon jungle.

At 20, he attempted suicide-by-jaguar. Afterward he was apprenticed to a pirate. To please his mother, who did not take kindly to his being a pirate, he briefly managed a mink farm, one of the few truly dull entries on his otherwise crackling résumé, which lately included a career as a professional gambler.

From the NYTimes obit of John Fairfax and oh did I mention he rowed across the Atlantic…and the Pacific.

Congress gets two right

In a rare display of function, Congress extended the payroll tax cut and in the same deal they arranged to sell more spectrum, both good ideas and ones that I have argued for extensively. Frankly, I am pleased but surprised. Any inside knowledge on how this was accomplished?