Month: May 2012

Raghu Rajan polarizes with his essay

Greg Mankiw calls it wise, John Cochrane likes it, David Brooks likes it, and I liked it, but other people are upset or less impressed. Karl Smith flips out. Adam Ozimek points out one misunderstanding of the piece, not the only one I might add. The essay itself is here.

Ezra Klein argues that Rajan should not have presented long-term vs. short-term thinking as either/or (for more on the “false choices” view, read here). To be sure, some policies such as immigration reform help both the short and long-term problems. Still, any given dollar must be spent somehow and “the stimulus model” and “the long-term investment model” are indeed competing visions for the allocation of resources. Think of it as having to choose a rate of discount for evaluating expenditures. I say choose the low discount rate, which of course still may justify those forms of stimulus with long-term payoffs. Ezra also notes that long-term investments may require short-term sweeteners to pass, but I see that as an illustration of Rajan’s point, namely that we are not very interested in the long run for its own sake.

Once the problem is presented in sufficiently precise microeconomic language, we can see where the real choice has to be made, namely at the level of the discount rate.

Rajan wants to spend money as an investment model would suggest. There is an “investment drought,” including from our government, and the growth-inducing parts of discretionary spending are coming under increasing pressure. AD stimulus is/would be less effective with each passing day. Raghu’s case on this point is strong, maybe you don’t agree but I don’t see that the critics have grasped it with sufficient depth.

In the past, in other contexts, Karl Smith and Matt Yglesias have defended “muddle through” and short-term thinking in policy. I see the public choice literature — both theoretically and empirically — as suggesting political discount rates to be far too high. Climate change is Exhibit A, but other examples are numerous.

Krugman is upset at Rajan, but where to begin? He misunderstands Rajan on structural unemployment, for a start see Adam’s post of correction listed above. (In general Krugman has written and rewritten more or less the same post against structural unemployment at least a dozen times without responding to, or even presenting, a strong version of the argument. It’s an intellectual Turing test fail, and maybe I’ll cover this some other time.)

From Krugman, there is more:

Most important, as Karl Smith says, is the fact that Rajan’s injunction that we focus on long-run growth isn’t responsible — it’s deeply feckless. The truth is that we don’t know much about promoting long-run growth, whereas we know a lot about promoting short-run recovery — which is a very different problem. In practice, stroking your chin and talking about the long run is mainly an excuse for doing nothing.

I would find it more useful if Krugman simply stated his preferred discount rate, and whether he wishes to count highly uncertain results for nothing (I don’t think so).

In any case, Krugman gets it backwards. Any Martian visiting the economics blogosphere, or for that matter Krugman’s blog, could tell you that most of micro is a more or less manageable topic, whereas macro induces economists to start thinking of each other as idiots and fools.

More substantively, we know a fair amount about promoting growth, for instance read Alex’s The Innovation Renaissance, much of which has been endorsed by left-wing thinkers too. Read the new Acemoglu and Robinson book. Even Robin Wells thinks we know how to promote long-run growth.

One might try to draw a distinction between “once and for all” changes in output and permanent boosts to the rate of economic growth, a’la Solow. In this context, that won’t wash, even if it is otherwise a defensible distinction (debatable). If we could get many “one time” gains today, for five or ten years running, that would be excellent and would boost growth and create jobs, whether or not we would be boosting the rate of innovation twenty years out. Krugman in other contexts argues for such gains all the time and with great vehemence and certainty, not with the faux temporary agnosticism exhibited above.

Finally, Rajan is a case for testing Krugman’s oft-stated view that we should listen most seriously to those who have made good predictions in the past. Rajan was probably the best, more accurate, most serious, most detailed, and most non-Chicken Little predictor of the financial crisis. You might think that means he gets listened to today, or given the benefit of the doubt on interpretation, but apparently not.

The economics of geoengineering

“The odd thing here is that this is a democratizing technology,’’ Nathan Myhrvold told me. “Rich, powerful countries might have invented much of it, but it will be there for anyone to use. People get themselves all balled up into knots over whether this can be done unilaterally or by one group or one nation. Well, guess what. We decide to do much worse than this every day, and we decide unilaterally. We are polluting the earth unilaterally. Whether it’s life-taking decisions, like wars, or something like a trade embargo, the world is about people taking action, not agreeing to take action. And, frankly, the Maldives could say, ‘Fuck you all—we want to stay alive.’ Would you blame them? Wouldn’t any reasonable country do the same?”

Assorted links

1. The Hindenburg’s smoking lounge.

2. Marc Gunther on An Economist Gets Lunch.

3. “I can imagine a spoon being part of a dish.”, and patriotic kitchen skillet markets in everything.

4. An eleven-year-old boy takes a Stanford game theory class.

5. Markets in everything, evil child-stalking clowns, better teach your eleven-year-old some game theory.

6. Against chairs.

*The Moral Molecule*

That is the new book by Paul Zak, and the subtitle is The Source of Love and Prosperity, namely oxytocin. Here is a recent article by Paul, related to the book.

Why they hate Santa (the culture that is Scotland?)

The poster, which features a slightly demonic looking Father Christmas looming over a small boy, is part of the art student’s campaign to put an end to the commercialisation of Christmas and to launch an attack on the advertising industry’s targeting of children. “Santa gives more to rich kids than poor kids,” declares the poster, which will be on Glasgow’s Balmore Road.

“Santa Claus is a lie that teaches kids that products will make them happy. Before they’re old enough to think for themselves, the story of Santa has already got them hooked on consumerism. I think that’s more immoral than this billboard,” said Mr Cullen, who spent four years studying advertising before becoming disenchanted with the industry and switching to Glasgow School of Art’s environmental art course.

Here is more, and for the pointer I thank Jeremy Davis.

First license for driverless cars

…on Monday, Nevada became the first to approve a license for “autonomous vehicles” — in other words, cars that cruise, twist and turn without the need for a driver — on its roads.

The license goes to Google, the Silicon Valley technology giant known more for its search engine and e-mail service that nonetheless has been known to dive into other big ideas such as space elevators to Internet-enabled glasses.

The story is here, and for the pointer I thank John Chilton. I am curious to see how liability evolves.

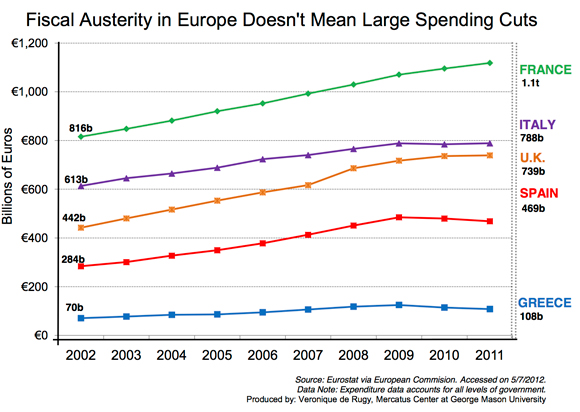

How savage has European austerity (spending cuts) been?

To be sure, there are particular small countries which have made serious spending cuts, in the Baltics most of all. But sometimes one hears it said that an anti-austerity strategy must be EU-wide as a whole, or that austerity is “a failed strategy for the eurozone,” or something similar. So perhaps it is worth looking at some numbers for the larger picture. Here is a graph which puts the matter in some perspective:

Veronique de Rugy, who compiled this data, writes:

First, I wish we would stop being surprised by what’s happening in Europe right now. Second, I wish anti-austerity critics would start acknowledging that taxes have gone up too–in most cases more than the spending has been cut. Third, I wish that we would stop assuming that gigantic “savage” cuts are the source of the EU’s problems. Some spending cuts have been implemented in a few countries. Also, if this data were adjusted for inflation (which I would prefer but the data isn’t available) it would possibly show a slight decrease and certainly a flatter line for all countries. However, the overwhelming take away from the European experience is that a majority of governments haven’t really implemented spending cuts, large or small, and some have even continued to grow.

There is further discussion at the link. Via Pat Lynch, here you will find OECD data, no country is spending below its 2004 level.

Addendum: My response from the comments section:

The real question addressed by this post is how bad spending cuts have been in nominal terms, keeping in mind in the short run it is supposedly nominal which matters (that said, gdp and population [and inflation] are not skyrocketing in these countries for the most part). It is fine to argue “due to automatic stabilizers, spending should have increased more than it did.” That is not how people phrase it, rather they are complaining rather vociferously about “spending cuts,” many of which are either imaginary or extremely small.

From the shrillness of responses, and by the frequency of frame switching, one can see how this post and this data have hit a raw nerve.

Cambodian motorbike protectionism

The [motorcycle taxi] drivers want a blanket ban on motorbike rentals for foreign tourists.

“We don’t want [tourists] to rent motorbikes, because foreign tourists don’t know Khmer habits when driving; they don’t comply with the law, and some drive by keeping on the left side, so that causes traffic accidents,” Heng Sam Om said.

The story is here. Will Koenig writes to me:

As someone who lived and worked in Cambodia for years, I find this hilarious. Traffic laws in Cambodia are rarely enforced, and “motordopes,” or motorcycle taxi drivers, are stereotyped as the worst drivers — including driving on the wrong side of the road. But they have formed a union and want to protect their market.

Assorted links

Where is the deflationary pressure in the eurozone “going”?

The difficulty of wording this question is indicative of Scott Sumner’s point about the poverty of our language. Here is Scott:

The most recent inflation rate in Greece is 1.7%, whereas Spain has 1.9% inflation. I don’t know about you, but I find those figures to be astounding. That’s not deflation, and yet Tyler’s clearly right that they are being buffeted by powerful deflationary forces.

1. This shows the poverty of our language. Economics lacks a term for falling NGDP, even though falling NGDP is arguably the single most important concept in all of macro, indeed the cause of the Great Depression. So we call it “deflation” which is actually an entirely different concept. I wouldn’t be the first to find connections between the poverty of our language and the poverty of our thinking.

2. Through experience I’ve learned that whenever a data point seems way off, there are probably multiple reasons. Thus Greece and Spain probably have less price level flexibility due to structural rigidities in their economies. And the inflation might be partly due to special factors like increased VAT or higher oil prices. Nonetheless, these sorts of depressions would have been associated with falling prices in the 1930s, so it’s not your grandfather’s business cycle.

One option (not the only piece of the puzzle) is that automatic stabilizers, in the form of highly inefficient government jobs and government-privileged jobs, are maintaining consumption, at some level, in the periphery economies. The deflationary pressures are being driven by the collapse of intermediation and are being “taken out” in the form of lower investment and lower capital maintenance. Look for instance at the M3 collapse in Italy.

This would have a few implications. First, the fiscal austerity story becomes more obviously secondary to the deflationary story, though not irrelevant. If the fiscal austerity story were driving the deflationary pressures, you might expect to see lower rates of price inflation, unless you think it all can be pinned on VAT increases (doubtful). Second, it is probably a more pessimistic view, since it implies things only look as good [sic] as they do because in essence current consumption is being funded by eating into capital growth and maintenance.

Third, given high rates of unemployment in Spain and Greece, those economies should not be operating at or near full capacity. High rates of price inflation suggests the importance of bottlenecks, which in turns means this is an AD and also an AS story, and not just a pure AD story.

I would stress the speculative nature of this discussion. In any case this is an extremely important but radically underdiscussed issue. It makes a lot of different theories look bad, and thus makes it harder to maintain an attitude of thundering certainty.

Good news from Africa

From Michael Clemens:

If you’re sick of the sad, hopeless stories coming out of Africa, here’s one that made my year. New statistics show that the rate of child death across sub-Saharan Africa is not just in decline—but that decline has massively accelerated, just in the last few years. From the middle to the end of the last decade, declines in child mortality across the continent plummeted much faster than they ever had before.

These shocking new numbers are in a paper released today by Gabriel Demombynes and Karina Trommlerová in the Kenya office of the World Bank.

The figures can be found at the link.

Thoughts this morning

There isn’t a proper policy response for every need.

That is from Bob Samuelson. His stance on monetary policy is not mine, but still these are neglected words.

I also see just how much economists are doing macroeconomic analysis without using the concept of trust. Following yesterday’s elections, including in France, trust among the eurozone nations went down. That makes the chance of a good outcome less likely, not more likely. It is painful to admit this, but things still could get much worse and now they are likely to do so. A seventeen-member currency zone (scary just to type those words) has to be based on trust and this one isn’t, least of all now. There is little reason to think that Hollande can browbeat the Germans into picking up more of the bill, and if the Germans perceive their former French partner as an unreliable ally, this becomes all the less likely .

Jim Manzi’s *Uncontrolled*

The subtitle is The Surprising Payoff of Trial-and-Error for Business, Politics, and Society, with an emphasis on RCT.

This is a truly stimulating book, about how methods of controlled experimentation will bring a new wave of business and social innovation. Here is an Eric Posner review. Here is a Kirkus review. There will be more. Kevin Drum offers good remarks.

Assorted links

1. On Posner and Weyl, John Cochrane is essentially correct.

2. Peter Thiel lecture notes on attracting venture capital.

3. Who complains the most about political polarization”: the polarized.

Bertrand Russell’s 10 Commandments for Teachers

- Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.

- Do not think it worth while to proceed by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light.

Never try to discourage thinking for you are sure to succeed.

- When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavour to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory.

- Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found.

- Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you.

- Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

- Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent that in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter.

- Be scrupulously truthful, even if the truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it.

- Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool’s paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness.

Hat tip: Brainpickings.