Month: August 2013

Amazon will offer free shipping to Singapore (and India)

Matt will be excited:

Popular online shopping site Amazon now provides free shipping to Singapore.

As long as shoppers in the country make a purchase of SGD$160 (USD$125) or over, they will be entitled to this free shipping under the site’s “Free AmazonGlobal Saver Shipping” program.

This new privilege, which also applies to consumers in India, was announced on the website on Friday.

The qualified amount to be spent by shoppers for the free shipping does not include import fees, gift-wrap charges, duties and taxes.

The free shipping is only provided to online shoppers purchasing goods sold directly by Amazon and not by their third party retailers.

The goods purchased must also be eligible for the AmazonGlobal program, which makes up a majority of the site’s product catalog, ranging from automotive products, electronics and jewelry to name a few.

However, shoppers need to make sure that the goods to be shipped do not exceed 20lbs. (9 kg) or they will not qualify for the free shipping service.

The link is here.

*Affordable Excellence*

The author is William A. Haseltine, the subtitle is The Singapore Health System, and the Kindle edition is itself an…affordable excellence at $0.00.

This book is a clear first choice on the Singapore health system and everyone interested in health care economics, or Singapore, should read it. It is short, clear, and to the point. And anyone interested in public policy or fiscal policy must, these days, be interested in health care economics.

Singaporeans have some of the best health care outcomes in the world and yet the system consumes only four (!) percent of gdp. Here is one short bit:

Private expenditure in Singapore amounted to around 65 percent of the total national expense (2008). Note that this includes payments out of the government-run MediShield scheme and related insurance schemes, MediSave accounts, and other private insurance schemes or employer-provided medical benefits. The figure for the United States is 52 percent, 17 percent for the United Kingdom, and 18 percent Japan. Singapore’s relatively high private expenditure is a direct result of the government’s efforts to shift more of the cost burden to consumers than do most other countries.

Before you pure libertarians get too happy, however, note that public sector hospitals account for about 80% of all patient hours and there is a single payer system for catastrophic expenditures.

Definitely recommended, at this price or even the paperback for $20.00.

By the way, here are some changes they likely will be making to the Singaporean health care system, moving it closer to traditional welfare state policies (for better or worse).

The new Emily Oster book

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong-and What You Really Need to Know.

It’s out, and if I hadn’t been giving talks in Singapore and eating pepper crab, I would have read and reviewed it by now. I will read it as soon as I can and of course I pre-ordered it once I heard about it, despite my lack of direct connection to the topic…

Assorted links

1. Zebra vs. wildebeest traffic jam, zebras do OK.

2. Japanese workers fear The Great Reset.

3. Orange is the New Green, on the economics of prisons. And very good profile of Mandy Patinkin.

4. Guidelines for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles at Burning Man.

5. Do our brains pay a price for GPS?

6. Malcolm Gladwell responds on 10,000 hours of practice.

7. Krugman on EM bubbles; “So, the flood of money into emerging markets now looks in retrospect like another bubble.” The data really are supporting this. Must a defense of QE therefore be non-cosmopolitan?

President Obama’s new higher education plan

Here is one summary:

“Early Thursday, he released a plan that would:

- Create a new rating system for colleges in which they would be evaluated based on various outcomes (such as graduation rates and graduate earnings), on affordability and on access (measures such as the percentage of students receiving Pell Grants).

- Link student aid to these ratings, such that students who enroll at high performing colleges would receive larger Pell Grants and more favorable rates on student loans.

- Create a new program that would give colleges a “bonus” if they enroll large numbers of students eligible for Pell Grants.

- Toughen requirements on students receiving aid. For example, the president said that these rules might require completion of a certain percentage of classes to continue receiving aid.”

There is another summary here.

So far I don’t get it. There seems to be plenty of information about colleges, and I doubt if a federal rating system would improve on those ratings already privately available. To the extent that federal system became focal, the incentives to game and scheme it would become massive, and how or whether to punish the gamers, if and when they are caught, would be a political decision. I don’t see that as healthy.

Given that previous educational subsidies mostly are converted into higher rates of tuition and thus captured by the school, the second plank would simply boost the subsidy to high performing colleges. There are plenty of ways to do that and in any case it doesn’t seem to help today’s marginal students, who probably cannot do well in those environments in any case. Furthermore colleges with high graduate earnings are very often those located in or near high-paying cities. Should we be subsidizing on that basis? Should we be giving colleges an incentive to identify and deny admission to potential lower earners? Do we really want the federal government helping to crush humanities majors? And I don’t see that the kind of rating system under discussion here is measuring actual value added, ceteris paribus of course.

I am not opposed to tougher requirements for aid recipients, but again there is a danger of gaming. For instance the aid recipients might simply choose easier classes and majors and aid-hungry colleges might very well accommodate them and make things as easy as they need to.

On the third plank, I don’t think the problem is that Pell Grant recipients cannot get into a good enough college. The problem, insofar as there is one, relates to how well they do once they show up, given what is often inadequate preparation. Encouraging now-rejecting colleges to accept them will if anything lure them into environments they are not capable of handling.

I would find it helpful if this proposal would outline the core, underlying theory of market failure in higher education, and then how these ideas would fix it. It is difficult for me to put that argument together in my mind. I do get the intuitive reason why “aid should be tied to outcomes.” But presumably students, who already have by far the most at stake in choosing a college, already allocate their own dollars and aid dollars on the basis of outcomes. If that process isn’t broken, this plan seems to address a pseudo-problem. If that process is broken (misguided students?), we need to know whether this plan really will fix the kink in the system. For instance if students cannot right now choose the schools offering the best expected outcomes for them, this plan seems to work mighty hard to get the schools to do the choosing for them, but in reality only ends up putting the students into tougher and less appropriate institutions. Can you spell “remedial”? In any case, under these assumptions, it would seem to be the students who need the fixing, not the schools. And so on.

I do like this part:

Further, the administration is promising to issue “regulatory waivers” for “high-quality, low-cost innovations in higher education, such as making it possible for students to get financial aid based on how much they learn, rather than the amount of time they spend in class.”

Overall the ideas here strike me as underdeveloped in terms of logic. Perhaps the plan will have positive effects simply through the “bully pulpit” medium.

First lecture for International Trade

You don’t need to start early, but here is the first reading assignment for International Trade:

Bernhofen, Daniel and John C. Brown. 2005. “An Empirical Assessment of the Comparative Advantage Gains from Trade: Evidence from Japan.” American Economic Review.

Autor, David H. David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence from Local Labor Markets.” NBER Working Paper.

Acemoglu, Daron, David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “Import Competition and the Great US Employment Sag of the 2000s.” NBER Working Paper.

Feenstra, Robert C. 2008. “Offshoring in the Global Economy.” Ohlin Lecture Series, pp.1-47 only.

Grossman, Gene M. and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. 2006. “The Rise of Offshoring: It’s Not Wine for Cloth Anymore.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Also watch the two videos on comparative advantage at MRUniversity.com, and the video Sources of Comparative Advantage, they are located in the class on development economics.

The financial unraveling of southeast Asia

It is now well underway. The stock market is Indonesia had several big loss days in a row, with some daily drops over five percent, and their credit-driven economic expansion seems to be over. Weaknesses in commodity markets will hurt them and they did not use their boom to invest sufficiently in future productive capacity, instead preferring to ride upon the glories of higher resource prices and growing credit. The central bank is burning reserves and starting to worry about an eventual crisis scenario.

I am puzzled by Krugman’s take on the rupee. I would not argue that the weaker rupee is bad per se, but rather it is a symptom that an earlier overvaluation of India’s economic prospects is now over. The country is, sorry to say, the “sick man of Asia,” economically speaking that is. (Or more literally in terms of public health, for that matter.) Here is my May 2012 column on India, which I think has held up very well. One can only hope that this financial crisis will bring reforms comparable to those of the early 1990s; otherwise the momentum for better policies appears to have been exhausted. Right now the country has about the worst legal system in the world (North Korea and a few other outliers aside) and the ten-year yield has been popping over ten percent. It is shifting from a better multiple equilibrium to a worse one and foreigners are having second and third thoughts about further investing.

The Thai economy has shrunk for two consecutive quarters and total debt (public and private) to gdp ratio is now about 180 percent. Malaysia also has serious debt problems. The uncertainty coming out of China is not helping either.

Singapore is doing fine.

I don’t expect these crises to have serious “knock on” problems for the developed nations, but hundreds of millions of vulnerable individuals now face a much worse economic future, at least in the short to medium term.

Addendum: There is also mounting evidence that QE has been to some extent responsible for southeast Asian financial bubbles, market monetarist evidence one might say, if I may be allowed to needle Scott. Call it Austro-Indonesian business cycle theory.

Assorted links Singapore

If all has gone well, I am now in Singapore, so here are some relevant links:

1. Stephen Wiltshire’s aerial view of Singapore, drawn from memory.

2. Singaporean women are starting to marry Chinese men.

3. The government is concerned that too many public servants are visiting Singaporean casinos.

4. Pop Yeh Yeh: Psychedelic Rock from Singapore and Malaysia 1964-1970, an excellent CD, especially if you approach it with the right sense of humor.

The Government Profits from Student Debt Defaults

Matt Taibbi’s expose of Federal educational loan programs is over-the-top and not balanced but it does have some shockers. Most importantly, according to Taibbi, the Federal government makes a profit on student defaults.

While it’s not commonly discussed on the Hill, the government actually stands to make an enormous profit on the president’s new federal student-loan system, an estimated $184 billion over 10 years, a boondoggle paid for by hyperinflated tuition costs and fueled by a government-sponsored predatory-lending program that makes even the most ruthless private credit-card company seem like a “Save the Panda” charity.

…In 2010, for instance, the Obama White House projected the default recovery rate for all forms of federal Stafford loans (one of the most common federally backed loans for undergraduates and graduates) to be above 122 percent. The most recent White House projection was slightly less aggressive, predicting a recovery rate of between 104 percent and 109 percent for Stafford loans.

The government claims the net after costs is less than 100%:

..Still, those recovery numbers are extremely high, compared with, say, credit-card debt, where recovery rates of 15 percent are not uncommon…. After the latest compromise, the 10-year revenue projection for the DOE’s lending programs is $184,715,000,000, or $715 million higher than the old projection – underscoring the fact that the latest deal, while perhaps rescuing students this coming year from high rates, still expects to ding them hard down the road.

The loans are profitable even when the student defaults because the government has ways of making people pay:

…”Student-loan debt collectors have power that would make a mobster envious” is how Sen. Elizabeth Warren put it. Collectors can garnish everything from wages to tax returns to Social Security payments to, yes, disability checks. Debtors can also be barred from the military, lose professional licenses and suffer other consequences no private lender could possibly throw at a borrower.

The upshot of all this is that the government can essentially lend without fear, because its strong-arm collection powers dictate that one way or another, the money will come back. Even a very high default rate may not dissuade the government from continuing to make mountains of credit available to naive young people.

The government has also made sure that many laws, such as the Truth in Lending law, do not apply to student loans.

Some student debt can make sense but when 40% of students drop out of college, when even the graduates do not graduate with the degrees that pay and when the job market is weak, student debt can be life-crippling:

…Bottomless credit equals inflated prices equals more money for colleges and universities, more hidden taxes for the government to collect and, perhaps most important, a bigger and more dangerous debt bomb on the backs of the adult working population.

Guillermo Calvo on Austrian business cycle theory

Don’t worry too much about the failings of the Austrian economists themselves, rather focus on what we can learn from them. That is the tack taken by Guillermo Calvo in a recent paper (pdf), here is one excerpt:

I will argue that the Austrian School offered valuable insights – disregarded by mainstream macro theory…Over‐extension of credit was at center stage of the Austrian School theory of the trade (or business) cycle, but authors differed as to the factors responsible for excessive credit expansion. Mises (1952), for instance, attributed excessive expansion to central banks’ propensity to keeping interest rates low in order to ensure full employment at all times. As inflation flared up, interest rates were raised causing recession. Thus, under his view the cycle is triggered by pro-cyclical monetary policy with a full-employment bias which was not consistent with inflation stability. Hayek (2008), on the other hand, dismissed von Mises explanation, not because it was not a good depiction of historical events, but because he thought that instability is something inherent to the capital market and, in particular, it is related to what might be called the banking money multiplier mirage. His discussion conjures up contemporary issues, like securitized banking, for example. At the risk of oversimplifying, Hayek’s views, a phenomenon that seems central to his trade cycle theory is that credit expansion by bank A induces deposit expansion in bank B who, in turn, has incentives to further expand credit flows, etc. If bank A makes a mistake, the money-multiplier mechanism amplifies it. This is reminiscent of misperception phenomena stressed in Lucas (1972). Hayek’s discussion does not exhibit the same degree of mathematical sophistication but focuses on a richer set of highly relevant issues. For example, that credit expansion is not likely to be evenly spread across the economy, partly because of imperfect information or principal-agent problems. This implies that credit expansion is likely to have effects on relative prices which are not justified by fundamentals. Shocks that impinge on relative prices are hardly discussed in mainstream close-economy macro models. Hayek’s theory is very subtle and shows that even a central bank that follows a stable monetary policy may not be able to prevent business cycles and, occasionally, major boom-bust episodes. Unfortunately, Hayek does not quantity the impact of perception errors…

That is a bit long-winded, so here is how I would express some related points:

1. Once you cut through the free market (or anti-market rhetoric), the Austrian theory is not as different from Minsky’s as it sounds at first. And both sides hate it when you say this.

2. There may be a fundamental impossibility in maintaining orderly credit relations over time and the more sophisticated versions of the Austrian theory get at this. Keynes thought that too, but arguably “the liquidity premium of money itself” is a red herring when trying to understand this issue. In that sense Keynes may have been a step backwards.

3. The Austrian theory may require a rather “brute” behavioral imperfection concerning naive short-run overreactions to market prices, quantities, and flows. For reform economies, newly developing economies, and economies coming off a “great moderation,” this postulate may not be entirely unreasonable.

4. That credit booms precede many important busts, and play a causal role in those busts, and shape the nature of those busts, is a deeper point than Keynes let on in the General Theory.

5. One should never use the Austrian theory to dismiss the relevance of other, complementary approaches, most of all those which stress the dangers of deflationary pressures.

6. I don’t exactly agree with Calvo’s Mises vs. Hayek framing as stated.

The paper is interesting throughout and also offers a good discussion of Mexico’s peso crisis, and the point that, while allowing a deflationary contraction is a big mistake, simply trying to reflate won’t set matters right very quickly because there are real, non-monetary problems already baked into the contraction.

The original pointer is from Peter Boettke, who discusses the piece as well.

Jakarta notes

The National Museum is a scatter shot but revelatory assemblage of Javanese gold, gamelan sets, jeweled swords, Papuan wooden sculpture, puppets, Sumatran textiles, and much, much more. It could be the world’s best museum you’ve never heard of. The museums here have yet to figure out price discrimination, namely that they can charge tourists more than fifty cents for admission.

There is an excellent modernist mosque (more photos here). The shopping malls are surprisingly attractive and advanced, images here. There is one under construction called “St. Moritz,” without irony or need of irony.

No plan can be executed in a timely manner without running into the detour of street food, unless of course you are stuck in one of the shopping malls. In those malls there are extensive food courts but Japanese food is more popular than Indonesian dishes.

Taxi drivers don’t seem to know how to get anywhere. It is possible that Indonesians drive on the left because the Dutch once did.

A fork and spoon is more useful than a fork and knife for (almost) anything worth eating.

Although Jakarta is hardly a backwater, on plenty of streets outside the center I found people staring at me and once they even asked if they could take my photo. Few people speak English.

Overall this is an underrated tourist destination. It is the world’s most populous Muslim country, a Muslim democracy, and Southeast Asia’s largest city. There are many reasons to go, and few reasons not to go, distance aside.

Ten years of Marginal Revolution

A number of people tell me that today is the ten year anniversary of Marginal Revolution. Maybe I should have readied a big, retrospective post of all that has changed in the blog, or all that has changed with me, or something like that. The reality is that I was too busy reading stuff, and traveling, and writing, and grading comprehensive exams and preparing for class, to even notice. Maybe that’s the proper retrospective right there.

Thank you all for reading!

Why have corporate profits been high?

Jeremy Siegel reports:

…David Bianco, chief equity strategist at Deutsche Bank, has shown that most of the margin expansion over the past 15 years has come from two factors: the increased proportion of foreign profits, which have higher margins because of lower corporate tax rates; and the increased weight of the technology sector in the S&P 500 index, a sector that usually carries the highest profit margins.

Higher profit margins also result from stronger balance sheets. The Federal Reserve reports that since 1996, the ratio of corporate liquid assets to short-term liabilities has nearly doubled, and the proportion of credit market debt that is long term has increased to almost 80 per cent from about 50 per cent. This means many companies have locked in the recent record low interest rates and will be much less sensitive to any future increase in rates, keeping margins high.

New evidence on anchoring effects

One Swallow Doesn’t Make a Summer: New Evidence on Anchoring Effects

Zacharias Maniadis, Fabio Tufano & John List

American Economic Review, forthcomingAbstract:

The experimental method is taking on increasing import within the economic science. We present a theoretical framework that provides insights into the optimal usage of the experimental method and the appropriate interpretation of experimental results. A key insight is that the rate of false positives depends not only on the observed significance level, but also on statistical power of the test and research priors. Through the lens of our model, we argue that most ‘surprising’ results published in the top scientific journals are likely false. As an example, we present evidence that a celebrated study with far-reaching economic implications reports results that are not replicable. The bad news is that this study is just one of hundreds that will not replicate. The good news is that a little replication goes a long way: a few independent replications dramatically increase the chances that the original finding is true.

The second link in the list, “How Economists (Mis)Use Experimental Methods,” provides an ungated pdf to the piece. The top link has an AEA member gate.

Hat tip goes to Kevin Lewis.

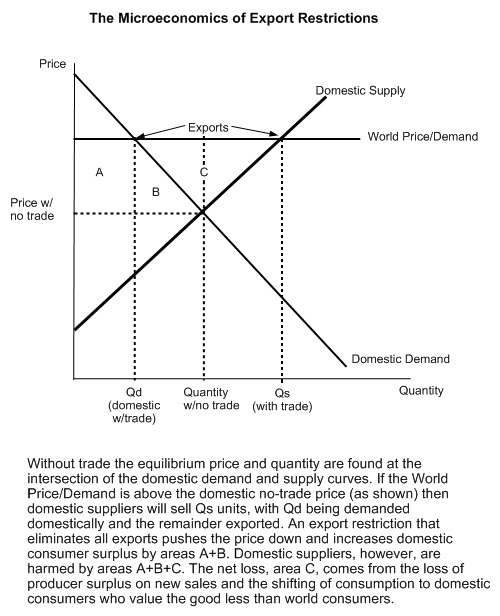

The Microeconomics of Export Restrictions

The typical protectionist measure is a limit on imports such as a tariff or a quota. Restrictions on exports are less common and less discussed but proposals to restrict the exports of natural gas have been in the news recently so perhaps a quick refresher on the protectionism of export restriction is in order. Restrictions on imports harm domestic demanders and benefit domestic suppliers but the harm is greater than the benefit so restrictions on imports create a net social loss. The basic result on export restrictions is similar, export restrictions benefit domestic demanders and harm domestic suppliers but the harm is greater than the benefit so restrictions on exports create a net social loss. The figure gives the analysis. As with import restrictions, the arguments for export restrictions soon turn to spillovers, networks effects, and other second round arguments. Without dismissing these in any particular case, the basic analysis suggest we should be wary of such arguments–the transfer always creates political opposition and any second round gains would have to be larger than the first round net benefits.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments. In brief he argues for the tax on Georgist grounds. Just because natural gas comes from land, however, doesn’t make a tax on natural gas equivalent to a tax on land. It’s the value of unimproved land that should be taxed not the value of the improvements, namely the extraction of the gas.