Month: August 2013

The Animals are Also Getting Fat

In a remarkable paper Allison et al. (2011) gather data on the weight at mid-life from 12 animal populations covering 8 different species all living in human environments. Dividing the sample into male and female they find that in all 24 cases animal weight has increased over the past several decades.

Cats and dogs, for example, both increased in weight. Female cats increased in body weight at a rate of 13.6% per decade and males at 5.7% per decade. Female dogs increased in body weight at a rate of 3% per decade and males at a rate of 2.2% per decade.

One ready, although not necessarily correct explanation, is that fat people feed their cats and dogs more and exercise them less. Thus, the authors also looked at animals not directly under human control such as rats.

…For the 1948–2006 time period, male rats trapped in urban

Baltimore experienced a 5.7 per cent increase in body

weight per decade from 1948 to 2006 and a nearly

20 per cent increase in the odds of obesity. Similarly,

female rats trapped in urban Baltimore experienced a

7.22 per cent per decade increase in body weight, along

with a 26 per cent increase in the odds of obesity.

that too has a ready, although not necessarily correct, explanation:

… just as human real wealth and food

consumption have increased in the United States, rats

which presumably largely feed on our refuse, may also

be essentially richer.

To counter both of these objections the authors do something very clever, they gather data on the weight of control mice used in many different experiments over decades.

Among mice in control groups in the National Toxicology

Programme (NTP), there was a 11.8 per cent

increase in body weight per decade from 1982 to 2003

in females coupled with a nearly twofold increase in the

odds of obesity. In males there was a 10.5 per cent

increase per decade.

Control mice are typically allowed to feed at will from a controlled diet that has not varied much over the decades, making obvious explanations less plausible. Could mice have gained weight due to better care? Possibly although that is speculative.

More generally, there are specific explanations for the weight gain in each of the animal populations, just as there are for humans. Each explanation looks plausible taken on its own but is it plausible that each population is gaining weight for independent reasons? Could there instead be a unifying explanation for the weight gain in all populations? No one knows what that explanation is: toxins? viruses? epigenetic factors? I am not ready to jump on any of these bandwagons and in some cases the author’s samples are small so I am not yet fully convinced of the underlying facts, nevertheless this is intriguing and important research.

Hat tip: David Berreby writing in Aeon about The Obesity Era.

Smart Phone Ethics

Here is David Pogue, an excellent technology reporter but a lousy economist, reviewing the Moto X in the NYTimes:

You get your customized phone within four days, courtesy of Feature 2: it’s assembled right here in these United States. The components are still made in Asia, but they’re put together in Texas — you can lose less sleep worrying about underpaid Chinese workers.

David does not explain how a decrease in the demand for Chinese workers increases Chinese wages. Hint: It doesn’t. Perhaps, however, I have done David a disservice; although his argument fails as economics it succeeds as psychology. People who buy American probably will worry less about underpaid Chinese workers. Out of sight, out of mind.

Addendum: Adam Smith’s thoughts on China and ethics, most notably the importance of using reason not emotion to make ethical decisions, remain relevant.

*A Call to Arms*

The author is Maury Klein and the subtitle is Mobilizing America for World War II, and it weighs in at almost 900 pp. So far it is quite good, and well-written, though fairly slow in getting off the ground. Here is one bit:

The navy was in no better shape. It too suffered from an antiquated organization and sclerotic leadership that still looked back to the last war. When Frank Knox took office, his staff included only a military aide and some secretaries. The navy had six bureaus but no central procurement authority and hardly any knowledge of or statistics on the proposed expansion program. Nor did it have any inventory of existing stocks or catalog of facilities or any semblance of long-range production planning. Its contracting machinery was primitive and glacial. James Forrestal, occupying the new position of undersecretary, had neither office nor staff nor defined duties. He and Knox would have to start from scratch, often butting heads with an entrenched officer corps.

Here is a useful WSJ review.

Two movies about killing

The first is “The Attack,” directed by a Lebanese-American and set mostly in Tel Aviv and Nablus. It has reportedly been banned in at least 22 Arab countries and in the Middle East it can be seen only in Israel. The plot line is that a prominent Arab Israeli surgeon, living in Tel Aviv, discovers that his deceased wife was in fact the perpetrator of a suicide bombing.

Here is a New York Times review, but the movie admits of multiple interpretations more than most of its Western press lets on. Because of a few nude scenes, the director could not find a Palestinian woman to play the lead female role and so he chose a Moroccan.

The second is “The Act of Killing,” which consists of interviews with Indonesian gangsters and murderers from the 1965 pogroms. The perpetrators are given a chance to stage, reenact, and ponder their deeds, all captured on camera. This is the most remarkable Hobbesian “document” I have experienced and the ways in which it is compelling go so far beyond other movies that there is no relevant point of comparison and I mean that in a way which is flattering to this movie. Perhaps imagine the petty tyrant scenes of The Sopranos or Donnie Brasco multiplied fifty or one hundred times in intensity. Werner Herzog nailed it: “I have not seen a film as powerful, surreal, and frightening in at least a decade… it is unprecedented in the history of cinema.” It is also a compelling meditation on the human need for narrative and how we do not know what we have done until we start telling it, and even then the process of telling keeps us from the real truth.

Both movies are rich in social science and you should make every attempt to see them.

Assorted links

1. Sensitivity training for Geoffrey Miller.

2. Stimulus for the Spanish postal service.

3. Vietnamese bubbles in leech prices for the Chinese.

4. Can people in fact appreciate better art?

5. Does it matter when foreigners are watching?

6. I am now doing some occasional blogging for LinkedIn, on labor market issues, my first post is here.

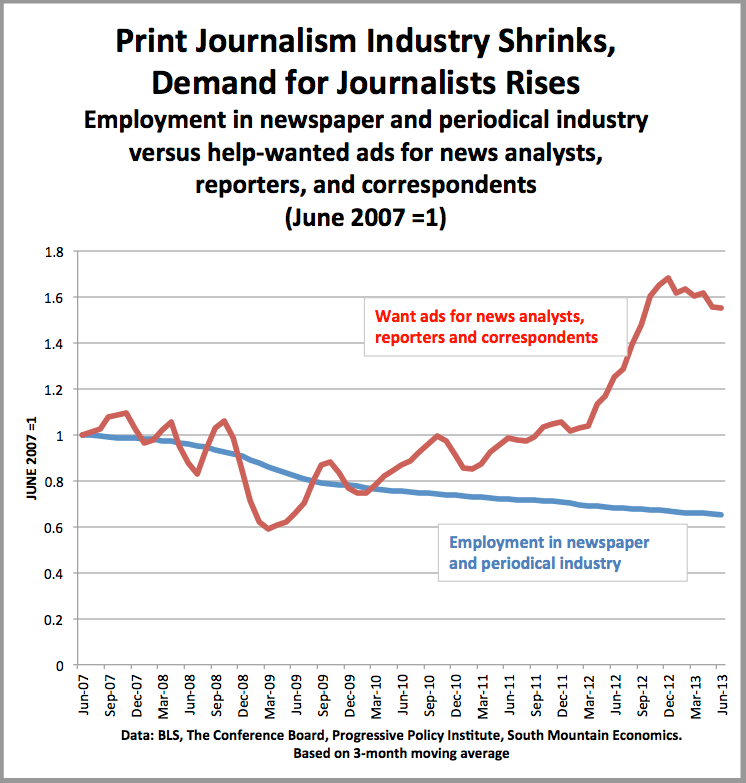

Creative Destruction in the News

From Michael Mandel who notes:

According to data from The Conference Board, the number of want ads for news analysts, reporter, and correspondents more than doubled from early 2010 to today! Moreover, it is noteworthy that the BLS annual series show a 25% gain in the number of working journalists from 2009 to 2012 (not shown on chart)

Now, let’s be realistic. I’m not saying that the true demand for journalists doubled between the beginning of 2009 and today, although given that no one was hiring in the depths of the recession, that statement might be literally true. In fact, the help-wanted series is an example of naturally-generated ‘big data’, meaning that it can be affected by changes in business practices, such as the way jobs are posted. The nature of journalism jobs may also be changing.

However, there seems little doubt that technology and innovation in journalism is creating new jobs in different industries even as the old companies and old industries are being undermined. I’m pretty sure that jobs at Politico are not being reported in the same industry as jobs at the Washington Post, even if Politico hires a WaPo reporter to cover more or less the same things.

As innovation accelerates, we’ll see more examples of this kind of divergence: Declining old industries, growing new jobs.

“No recovery for young people?” (The Great Reset)

In July 2013, just 36 percent of Americans age 16-24 not enrolled in school worked full-time, 10 percent less than in July 2007.

That is from Diana G. Carew, via Michael Mandel.

Is Amazon Art a doomed venture? Let’s hope so

I do not think it will revolutionize the art world:

Amazon has just announced that it’s partnered up with over 150 galleries and art dealers across the US to sell you fine art through its new initiative Amazon Art.

The site offers over 40,000 original works of fine art, showcasing 4,500 artists. That, perhaps unsurprisingly, makes it the largest online collection of art directly available from galleries and dealers. Partners in the project include Paddle8 in New York, the McLoughlin Gallery in San Francisco, and the Catherine Person Gallery in Seattle.

Last month, the Wall Street Journal reported that Amazon—which will reportedly take a 5 to 20 percent cut on all sales—was planning to launch the new service. At the time, it seemed that plenty of galleries thought that selling art online via Amazon may be distasteful. Clearly, that negative feeling hasn’t stopped Bezos & Co..

Given Amazon’s last attempt at selling art—a project with Sotheby’s back in 2000 — only lasted 16 months, it’ll be interesting to see how the initiative works out.

I expect the real business here to come in posters, lower quality lithographs, and screen prints, not fine art per se. And sold on a commodity basis. There is nothing wrong with that, but I don’t think it will amount to much more aesthetic importance than say Amazon selling tennis balls or lawnmowers.

Should you buy this mediocre Mary Cassatt lithograph for “Price: $185,000.00 + $4.49 shipping”? (Jeff, is WaPo charging you $250 million plus $4.49 shipping? I don’t think so. )

One enduring feature of the art world is that a given piece will sell for much more in one context rather than another. The same painting that might sell for 5k from a lower tier dealer won’t command more than 2k on eBay, if that. Yet it could sell for 10k, as a bargain item, relatively speaking, if it ended up in the right NYC gallery (which it probably wouldn’t). Where does Amazon stand in this hierarchy? It doesn’t look promising.

Their Warhols are weak and overpriced, even if you like Warhol. Are they so sure that this rather grisly Monet is actually the real thing? I say the reviews of that item get it right. At least the shipping is free and you can leave feedback.

I’ve browsed the “above 10k” category and virtually all of it seems a) aesthetically absymal and b) drastically overpriced. It looks like dealers trying to unload unwanted, hard to sell inventory at sucker prices. I’m guessing that many of these are being sold at multiples of three or four over auction price histories. Is this unexceptional John Frost worth even a third of the 150k asking price? Maybe not.

Amazon wouldn’t sell you a kitchen blender that doesn’t work, or that was triple the appropriate cost, so why should they sully their good name by hawking art purchase mistakes? If you’ve built the best web site in the history of the world, which they have, you may decide that quality control should not be tossed out the window. Much as I admire their shipping practices, what makes Amazon work for me is simply that they sell better stuff and a wider variety at cheaper prices. Why give that formula up by treading into a market where such an approach won’t make any money? Why compete in a market where an awesomely speedy physical delivery network means next to nothing?

Overall, I don’t see the advantage of Amazon over eBay in this market segment. One nice thing about eBay is that you can see if anyone else is bidding and also that surprise quality items pop up on a relatively frequent basis, due to a fully decentralized supply network. You also can hope for extreme bargains and indeed I have snagged a few in my time. On the new Amazon project, supply is restricted to a relatively small number of bogus, mainstream galleries, about 150 of them according to the publicity.

eBay has the advantage with “free for all,” and good galleries and auction houses have the advantage when it comes to certification and pricing reliability. I don’t see the intermediate niche that Amazon is supposed to be trying to fill.

I’m a big fan of Jeff Bezos buying The Washington Post, but if you’re looking for the case against that move, just click on that Monet purchase and see what happens.

Wu Jinglian

The first sentence of this MIT Press book — entitled Wu Jinglian — reads “Wu Jinglian is widely acknowledged to be China’s most influential and celebrated economist.”

Almost every page of this book is insightful on Chinese economics or politics or usually both together. And it will remind you that China is still ruled by the Communist Party. Wu Jinglian is a fan of James M. Buchanan and Douglass C. North, by the way. Here is Wu Jinglian on Wikipedia.

Recommended.

Assorted links

2. How good would LeBron James be at football? And a fun discussion of Jeff Bezos. Here is why WaPo is not a vanity project for Bezos. And Raghu Rajan has just been appointed RBI Governor.

3. The food culture that is Indiana.

4. Timur Kuran on political Islam, Turkey, and Egypt.

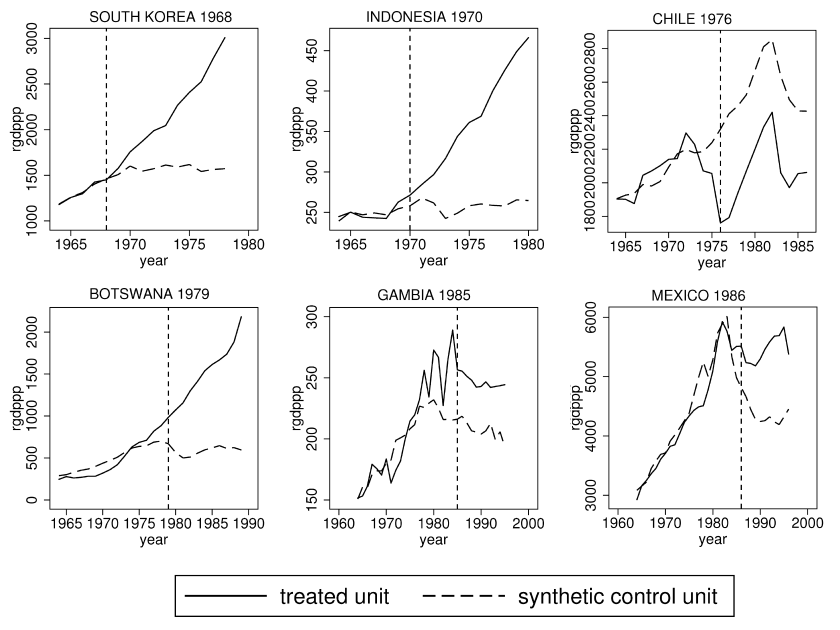

Liberalization Increases Growth

In Assessing Economic Liberalization Episodes: A Synthetic Control Approach (wp version), Billmeier and Nannicni evaluate economic liberalizations, defined as “comprehensive reforms that extend the scope of the market, and in particular of international markets,” over the period 1963-2005. The authors compare real per-capita GDP in treatment countries with that in a synthetic control, a weighted average of similar countries with the weights optimized so that the synthetic control matches as well as possible a variety of pre-treatment characteristics including secondary school enrollment, population growth, and the investment share as well as GDP. The results are often impressive, for example.

[In Indonesia] the average income over the years before liberalization is literally identical to that of the synthetic control, which consists of Bangladesh (41%), India

(23%), Nepal (23%), and Papua New Guinea (13%). After the economic liberalization in 1970, however, Indonesian GDP per capita takes off and is 40% higher than the estimated counterfactual after only five years and 76% higher after ten years.

Here is a selection of figures (see the paper for more). In each case the solid line is the liberalizing country and the dashed line the synthetic control.

To be sure, not all liberalizations are successful. In particular, liberalizations in Africa especially after 1991 appear to be less successful. Whether this is because these liberalizations were half-hearted, were not combined with other institutional improvements or because countries that liberalized earlier were better able to link to global supply chains, is unclear. See the paper for more discussion.

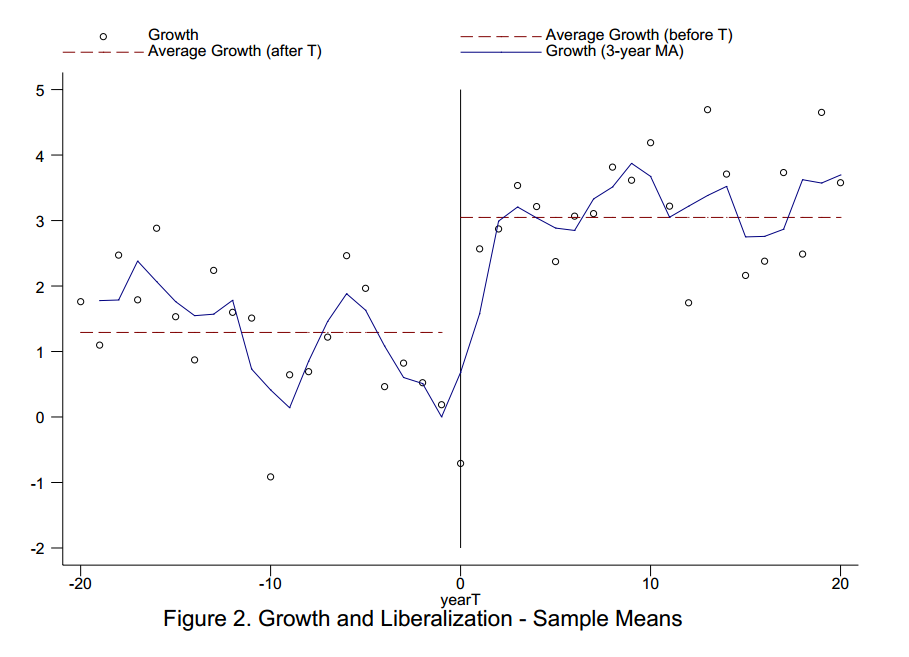

These results bolster similar earlier findings from Warciarg and Welch (2008) who, using different methods, examined the average effect of liberalizations on growth from a wide variety of countries over a 50 year period. They found that on average growth increased after liberalization by a remarkable 1.5 percentage points. Here is the key figure.

See Development and Trade: The Empirical Evidence, a video from MRU, for more on the WW study as well as other types of evidence.

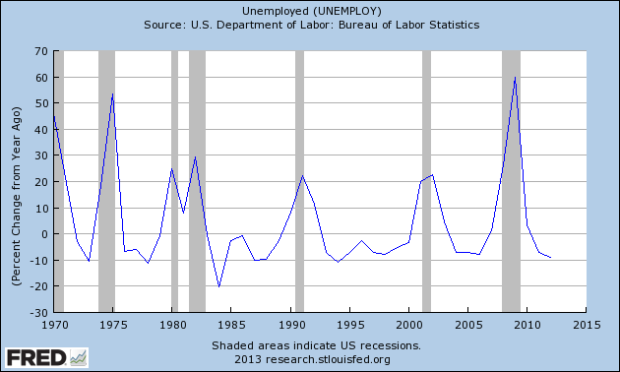

Has the U.S. labor market adjusted?

Via Ashok Rao, this is a scary chart:

If read “crudely,” the chart suggests that in terms of percentage changes, we already have seen a historically normal level of adjustment. There is an interesting discussion at the link.

By the way, if you’re not already, you all should be reading Ashok Rao.

Do consensual labor markets have a future in Germany?

The practice seems to be on a decline, according to this recent piece in The Economist:. For instance:

…the unions are continuing to lose members, as the older industries where they are entrenched trim jobs. Newer companies, especially in areas such as e-commerce, security firms and fitness studios, are “almost entirely without collective representation”, says Martin Behrens at the Hans Böckler Stiftung, a union-linked think-tank.

Workers at any German company with five or more employees can demand the creation of a works council. But in 2011 only 12.5% of all companies had one, down from 13.4% the year before. Only 659 German firms had supervisory boards with worker representatives in 2011, compared with 708 in 2007. Ironically, as America’s carmaking union seeks to bring Germany’s labour-market model into Volkswagen’s factory in Tennessee (see article), its future seems increasingly in doubt back home.

Here is a recent NYT piece on how Amazon’s labor practices clash with German union traditions.

Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook will own lots of content

These days the natural monopoly of Apple is looking less permanent, but here is what I wrote a short while ago:

I expect two or three major publishers, with stacked names (“Penguin Random House”), and they will be owned by Google, Apple, Amazon, and possibly Facebook, or their successors, which perhaps would make it “Apple Penguin Random House.” Those companies have lots of cash, amazing marketing penetration, potential synergies with marketing content they own, and very strong desires to remain focal in the eyes of their customer base. They could buy up a major publisher without running solvency risk. For instance Amazon revenues are about twelve times those of a merged Penguin Random House and arguably that gap will grow.

There is no hurry, as the tech companies are waiting to buy the content companies, including the booksellers, on the cheap. Furthermore, the acquirers don’t see it as their mission to make the previous business models of those content companies work. They will wait.

Did I mention that the tech companies will own some on-line education too? EduTexts embedded in iPads will be a bigger deal than it is today, and other forms of on-line or App-based content will be given away for free, or cheaply, to sell texts and learning materials through electronic delivery.

Much of the book market will be a loss leader to support the focality of massively profitable web portals and EduTexts and related offerings.

With the sale of The Washington Post to Jeff Bezos (btw not to the company), we have now taken one step down this road.

Assorted links

1. Memoir of Bombay.

2. Your Japanese toilet can be hacked.

3. Photos from a visit to the Yakuza.

4. Public unions and ACA nervousness.

5. I am pleased to have made this Time list of the best bloggers. The discussion of MR is here.

6. Free download of Calestous Juma, The New Harvest, a very good book on agriculture in Africa.

7. How do dogs show their love? And do they actually have mixed emotions toward you?