Month: March 2014

The Silicon Valley wage suppression conspiracy

Many readers have asked me what I think of the email chain which shows evidence that Silicon Valley firms conspired to hold wages down, by refusing to engage in competitive bidding for workers’ services.

I would suggest caution in interpreting this event. For one thing, we don’t know how effective this monopsonistic cartel turned out to be. We do know that wages for successful employees in this sector are high and rising. Many a collusive agreement has fallen apart once one or two firms decide to break ranks, as they usually do. Without legal enforcement, or without an NCAA-like clearinghouse enforcement structure (also backed by the law), it is hard to find examples of persistently successful monopsonistic labor-buying cartels. One reason is that workers can find means of switching firms which do not directly implicate the new hiring firm as the villain which plucked them away. The most successful collusive agreements are not usually monopsonistic and furthermore they are often based on self-sustaining and self-interested norms which do not require articulation in the form of incriminating emails.

A second point is this. Let’s say you knew that when you took a job at Apple or Google that no other Silicon Valley firm would bid you away. You don’t need to have explicit knowledge of the workings of the cartel, rather you simply observe that other people in your general position seem to stay put rather than receiving fantastic outside offers. Given that you have outside alternatives, you would demand, and receive, higher wages in the first place for moving to one of those firms. This actually would increase wage compression and limit inequality, albeit while decreasing efficiency. Still, workers as a whole would win back some of what they seemed to be losing, albeit not all of it.

Assorted links

1. O England how could ye?: Liverpool City Council trying to ban eating fish and chips from paper.

3. A ProteinPower guy obsessed with books (but I would say the crowd underlinings in Kindles are usually the worst passages from books, not the best or the most important). Here is his daily reading strategy, totally wrong for me it would be.

4. How might you invest in self-driving vehicles?

5. The homing skills of pythons. And are Marlborough girls unique?

6. Jeremy Stein understands the importance of the risk premium. And good analysis of The Americans.

Metadata Reveals Sensitive, Private Information

The President and other apologists for the NSA have defended the NSA’s illegal mass surveillance of US telephones by arguing that it’s “only” metadata, so “nobody is listening to our telephone calls.” But where, when, how long and to whom customers make phone calls does reveal information that could easily be used to blackmail, stifle and control. A group of computer scientists at Stanford’s Security Laboratory gathered information from volunteers who agreed to have an app on their cell phone mimic what the NSA collects. Here is an initial report.

At the outset of this study, we shared the same hypothesis as our computer science colleagues—we thought phone metadata could be very sensitive. We did not anticipate finding much evidence one way or the other, however, since the MetaPhone participant population is small and participants only provide a few months of phone activity on average.

We were wrong…The degree of sensitivity among contacts took us aback. Participants had calls with Alcoholics Anonymous, gun stores, NARAL Pro-Choice, labor unions, divorce lawyers, sexually transmitted disease clinics, a Canadian import pharmacy, strip clubs, and much more. This was not a hypothetical parade of horribles. These were simple inferences, about real phone users, that could trivially be made on a large scale.

…Though most MetaPhone participants consented to having their identity disclosed, we use pseudonyms in this report to protect participant privacy.

- Participant A communicated with multiple local neurology groups, a specialty pharmacy, a rare condition management service, and a hotline for a pharmaceutical used solely to treat relapsing multiple sclerosis.

- Participant B spoke at length with cardiologists at a major medical center, talked briefly with a medical laboratory, received calls from a pharmacy, and placed short calls to a home reporting hotline for a medical device used to monitor cardiac arrhythmia.

- Participant C made a number of calls to a firearm store that specializes in the AR semiautomatic rifle platform. They also spoke at length with customer service for a firearm manufacturer that produces an AR line.

- In a span of three weeks, Participant D contacted a home improvement store, locksmiths, a hydroponics dealer, and a head shop.

- Participant E had a long, early morning call with her sister. Two days later, she placed a series of calls to the local Planned Parenthood location. She placed brief additional calls two weeks later, and made a final call a month after.

We were able to corroborate Participant B’s medical condition and Participant C’s firearm ownership using public information sources. Owing to the sensitivity of these matters, we elected to not contact Participants A, D, or E for confirmation.

In other news, a former president believes that his email is being monitored. He is probably correct. Monitoring presidential candidates is all too realistic.

Fortunately, President Obama has announced that the bulk collection of phone calls will end. Dismantling that illegal program is a start. Obviously, this would not have happened without the revelations of Edward Snowden.

The multiverse is looking more likely

Or so I am told:

…those gravitational wave results point to a particularly prolific and potent kind of “inflation” of the early universe, an exponential expansion of the dimensions of space to many times the size of our own cosmos in the first fraction of a second of the Big Bang, some 13.82 billion years ago.

“In most models, if you have inflation, then you have a multiverse,” said Stanford physicist Andrei Linde. Linde, one of cosmological inflation’s inventors, spoke on Monday at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics event where the BICEP2 astrophysics team unveiled the gravitational wave results.

Essentially, in the models favored by the BICEP2 team’s observations, the process that inflates a universe looks just too potent to happen only once; rather, once a Big Bang starts, the process would happen repeatedly and in multiple ways.

There is more here. How should this change my behavior? Should I feel more or less regret? Take more or fewer risks?

For the pointer I thank Ami Evelyn.

Norman Borlaug was born 100 years ago today

In case you didn’t know.

How are the benefits distributed from Medicare Advantage?

There is a new NBER Working Paper by Mark Duggan, Amanda Starc, and Boris Vabson, here is the abstract, with the bold emphasis added by me:

Governments contract with private firms to provide a wide range of services. While a large body of previous work has estimated the effects of that contracting, surprisingly little has investigated how those effects vary with the generosity of the contract. In this paper we examine this issue in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program, through which the federal government contracts with private insurers to coordinate and finance health care for more than 15 million Medicare recipients. To do this, we exploit a substantial policy-induced increase in MA reimbursement in metropolitan areas with a population of 250 thousand or more relative to MSAs just below this threshold. Our results demonstrate that the additional reimbursement leads more private firms to enter this market and to an increase in the share of Medicare recipients enrolled in MA plans. Our findings also reveal that only about one-fifth of the additional reimbursement is passed through to consumers in the form of better coverage. A somewhat larger share accrues to private insurers in the form of higher profits and we find suggestive evidence of a large impact on advertising expenditures. Our results have implications for a key feature of the Affordable Care Act that will reduce reimbursement to MA plans by $156 billion from 2013 to 2022.

There is an ungated version here (pdf).

Assorted links

1. The marvelous floating stage in Bregenz. And fabric dancing, skip to 6:30 of the video.

2. This story about wealthy Raelian charity is stranger than you might expect.

3. Mercados por todo: un hotel para cadáveres.

4. Is elephant dung coffee the most expensive coffee on the planet?

5. John Cassidy reviews Piketty. And Russia’s 19 richest people have lost $18.3 billion since the invasion of Crimea.

6. The editor of Lancet is anti-scientific and full of mood affiliation (pdf).

7. Richard Epstein has a new book on the classical liberal constitution.

Will the current Bitcoin rules become obsolete?

One conclusion drawn by Kroll and his Princeton colleagues Ian Davey and Ed Felten is that those rules will have to be significantly changed if Bitcoin is to last. Their models predict that interest in “mining” for bitcoins, by downloading and running the Bitcoin software, will drop off as the number in circulation grows toward the cap of 21 million set by Nakamoto. This would be a problem because computers running the mining software also maintain the ledger of transactions, known as the blockchain, that records and guarantees bitcoin transactions (see “What Bitcoin Is and Why It Matters”).

Miners earn newly minted bitcoins for adding new sections to the blockchain. But the amount awarded for adding a section is periodically halved so that the total number of bitcoins in circulation never exceeds 21 million (the reward last halved in 2012 and is set to do so again in 2016). Transaction fees paid to miners for helping verify transfers are supposed to make up for that loss of income. But fees are currently negligible, and the Princeton analysis predicts that under the existing rules these fees won’t become significant enough to make mining worth doing in the absence of freshly minted bitcoins.

The only solution Kroll sees is to rewrite the rules of the currency. “It would need some kind of governance structure that agreed to have a kind of tax on transactions or not to limit the number of bitcoins created,” he says. “We expect both mechanisms to come into play.”

That kind of approach is common in established economies, which tame things like insider trading with laws and regulatory agencies and have central banks to shape economies. But many backers of Bitcoin prize the way it currently operates without centralized control, and would likely rebel at any suggestion of changing the rules.

The full article, which is here, has other points of interest. I would put the problem this way. It is easy to trust a non-proprietary network, and that is often cited as an advantage of Bitcoin, or for that matter as an advantage of a common language or a standard. At the same time, the non-proprietary nature of the network makes the rules much harder to change because there is no authority to mandate such a change. You will find related points in many papers of Joseph Farrell.

Hat tip goes to Andrea Castillo.

My TLS review of Frederick Taylor and Felix Martin

The Frederick Taylor book is The Downfall of Money: Germany’s hyperinflation and the destruction of the middle class, and Martin’s is Money: The Unauthorised Biography.

On Taylor I wrote:

It’s about time we heard the classic Weimar hyperinflation story from the side of governance, just as it is indeed illuminating to reread Hamlet while omitting the parts about the Prince.

Taylor has oddly little on monetary policy in his book, even though he clearly understands the core issues. On Martin’s book I wrote:

Like Taylor’s work, this is an excellent book to read, full of interesting history and insight, and very clear and well written. It is an overview of the history of money, and thought about money, yet through a more philosophical lens than is usually the case. It is not clear, however, if the central thesis of the book is either correct or relevant.

Martin tends to trace financial crises to the defects in underlying philosophies of money, such as whether money is viewed as a thing or as a sign. I also wrote this about the book:

Yet, to paraphrase Freud, sometimes a financial crisis is just a financial crisis.

If you click on the top link here and register for a trial period, you can read the review.

Should we teach the habits of highly effective people?

Faculty members at Alamo Colleges in San Antonio objected earlier this year to their chancellor’s move to make a course inspired in part by the popular self-help book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People part of the core curriculum. Instructors said they felt left out of the decision-making process and weren’t sure if the course, which would replace one of only two required humanities classes in the core, deserved that kind of curricular billing.

It is strange, is it not, that the attempt to teach habits of highly effective people is considered gauche and unworthy of the time of students? (It is unlikely that the objections stem from a belief that the wrong habits are being taught. That said, you can read more about the Mormon roots of Stephen Covey and his ideas here.) You can read more about the episode at Alamo Colleges here.

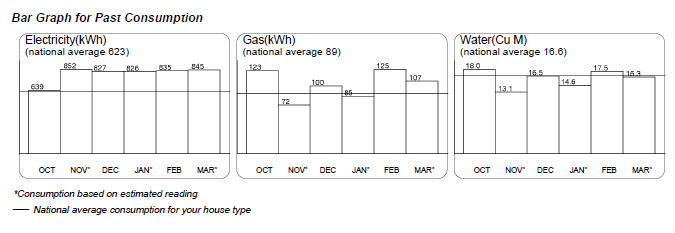

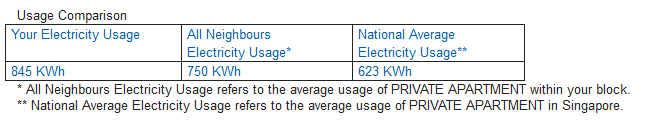

What do Singapore utility bills look like?

Are computers better at detecting real human pain?

In a fascinating project, researchers at University of California San Diego and the University of Toronto have found that computers are far better than humans at recognizing the difference between real and fake pain in the faces of test subjects. In fact, while humans could tell the difference 55 percent of the time, robots could tell it 85 percent of the time.

There is more here, and I thank Andrew Dresner for the pointer.

Assorted links

Facts about fame (in praise of college towns)

From Seth Stephens-Davidowitz in today’s NYT:

Roughly one in 2,058 American-born baby boomers were deemed notable enough to warrant a Wikipedia entry. About 30 percent made it through art or entertainment, 29 percent through sports, 9 percent through politics, and 3 percent through academia or science.

…Roughly one in 1,209 baby boomers born in California reached Wikipedia. Only one in 4,496 baby boomers born in West Virginia did. Roughly one in 748 baby boomers born in Suffolk County, Mass., which contains Boston, made it to Wikipedia. In some counties, the success rate was 20 times lower.

…I closely examined the top counties. It turns out that nearly all of them fit into one of two categories.

First, and this surprised me, many of these counties consisted largely of a sizable college town. Just about every time I saw a county that I had not heard of near the top of the list, like Washtenaw, Mich., I found out that it was dominated by a classic college town, in this case Ann Arbor, Mich. The counties graced by Madison, Wis.; Athens, Ga.; Columbia, Mo.; Berkeley, Calif.; Chapel Hill, N.C.; Gainesville, Fla.; Lexington, Ky.; and Ithaca, N.Y., are all in the top 3 percent.

Why is this? Some of it is probably the gene pool: Sons and daughters of professors and graduate students tend to be smart. And, indeed, having more college graduates in an area is a strong predictor of the success of the people born there.

But there is most likely something more going on: early exposure to innovation. One of the fields where college towns are most successful in producing top dogs is music. A kid in a college town will be exposed to unique concerts, unusual radio stations and even record stores. College towns also incubate more than their expected share of notable businesspeople.

African-Americans who grew up around Tuskegee did very well in achieving Wikipedia fame. Yet how much a state spends on education does not seem to matter. And this:

…there was another variable that was a strong predictor of Wikipedia entrants per birth: the proportion of immigrants. The greater the percentage of foreign-born residents in an area, the higher the proportion of people born there achieving something notable. If two places have similar urban and college populations, the one with more immigrants will produce more notable Americans.

The piece is fascinating throughout, and you will note that Seth is a Google data scientist with a Ph.d. in economics from Harvard. His other writings are here. Some of you may wish to see my book What Price Fame?

Uncertainty traps

Here is a new and interesting paper by Pablo Fajgelbaum, Edouard Schaal, Mathieu Taschereau-Dumouchel:

We develop a theory of endogenous uncertainty and business cycles in which short-lived shocks can generate long-lasting recessions. In the model, higher uncertainty about fundamentals discourages investment. Since agents learn from the actions of others, information flows slowly in times of low activity and uncertainty remains high, further discouraging investment. The unique equilibrium of this economy displays uncertainty traps: self-reinforcing episodes of high uncertainty and low activity. While the economy recovers quickly after small shocks, large temporary shocks may have nearly permanent effects on the level of activity. The economy is subject to an information externality but uncertainty traps remain even in the efficient allocation. We extend our framework to include additional features of standard business cycle models and show, in that context, that uncertainty traps can substantially worsen recessions and increase their duration, even under optimal policy interventions.

There is an ungated version here.