Month: March 2014

John B. Judis on *Genesis*

The subtitle of his book is Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. I am finding this book interesting, here is one good bit:

The call for a greater Syria reflected the prevailing sentiment among Palestine’s Arab intellectuals. Some notables who were active in the Muslim-Christian Associations wanted an Arab Palestine within the British Empire, but many of the activists and intellectuals, inspired by Faisal’s success, envisaged Palestine as “Southern Syria.”

…There was a good geographical as well as political argument for greater Syria. As subsequent events would reveal, Palestine lacked natural boundaries, especially in the north and south. There were looming disputes over water rights that could be avoided by combining Palestine and Syria.

…The British, fearful that the movement for a greater Syria would undercut their hold over Palestine, encouraged Palestine’s Arabs to think of themselves as Palestinian.

Overall the text offers a strongly non-sentimental account, does not whitewash any of the participants in the disputes, and it communicates how much early American policymakers , including Truman, were skeptical about what ended up happening. Today’s often-unquestioned assumptions were very often historically quite contingent. You can buy the book here.

The John Goodman health care plan

Here is one part of it:

There is something else we could do to promote universal health insurance: We could allow everyone — regardless of income — to enroll in Medicaid, and at the same time allow everyone on Medicaid to leave the program, claim the tax credit, and buy private insurance. This, of course, is the “public option” that the Left has been clamoring for. It’s hard to understand why conservatives are so resistant to it: If a private insurer can’t outperform Medicaid, it doesn’t deserve to be in the market.

The specific tax-credit levels I am proposing are the Congressional Budget Office estimates of the cost of enrolling new people in Medicaid. Under my proposal, people who are already eligible could use their tax credit to buy in, no questions asked, but people with higher incomes might have to pay a premium on top of their tax credit if they have higher-than-average expected costs. Health status wouldn’t be considered, but age and other factors would be. To prevent gaming of the system, no one would be able to move from one plan to another at a premium that is way below his total expected costs. (See below.)

This proposal may appear to be unconservative, but in fact it is consistent with minimizing the role of government. Medicaid would be an insurer of last resort, but, beyond their uniform tax credit, people who are not poor but enroll in Medicaid would not be getting an entitlement. They would have to pay their own way.

The full post is here.

Why blame only the Republicans?

When I blame people for their problems, Democrats and liberals are prone to object at a fundamental level. One fundamental objection rests on determinism: Since everyone is determined to act precisely as he does, it is always false to say, “There were reasonable steps he could have taken to avoid his problem.” Another fundamental objection rests on utilitarianism: We should always do whatever maximizes social utility, even if that means taxing the blameless to subsidize the blameworthy.

Strangely, though, every Democrat and liberal I know routinely blames one category of people for their vicious choices: Republicans…

Personally, I strongly favor blaming Republicans. I think 80% of the blame heaped on Republicans is justified. What mystifies me, however, is the view that Republicans are somehow uniquely blameworthy. If you can blame Republicans for lying about WMDs, why can’t you blame alcoholics for lying to their families about their drinking? If you can blame Republican leaders for supporting bad policies because they don’t feel like searching for another job, why can’t you blame able-bodied people on disability because they don’t feel like searching for another job?

Democrats and liberals who expand their willingness to blame do face a risk: You will occasionally sound like a Republican! But why is that such a big deal? Maybe you’ll lose a few intolerant hard-left friends, but they’re replaceable. By taking a reasonable step – broadening your blame – you can avoid the vices of moral inconsistency and moral nepotism. To do anything less would be… blameworthy.

That is from Bryan Caplan. As Robin Hanson once opined, “politics isn’t about policy.”

My own view is to minimize blame in all directions, but of course Bryan is correct in pointing out this inconsistency. Most people are willing to blame those whom they seek to lower in relative status, though I can’t say I really blame them for that.

(Dis)Honesty – A Documentary Feature Film

That is a new Kickstarter project from Dan Ariely and Yael Melamede.

For the pointer I thank Yogesh.

Assorted links

1. The upshot on The Upshot, the new David Leonhardt-run policy wonk venture from the NYT. I am very excited to see this project.

2. Kaleidic Economics produces its quarterly report on The Great Stagnation (pdf).

3. Dynamic pricing for Kiwi car parking.

4. Is acting psychologically problematic? And principles of autistic cooperation.

5. What are the ethics and economics of drug denial for “compassionate use” requests?

Elephant discrimination

Elephants are able to differentiate between ethnicities and genders, and can tell an adult from a child – all from the sound of a human voice.

This is according to a study in which researchers played voice recordings to wild African elephants.

The animals showed more fear when they heard the voices of adult Masai men.

Livestock-herding Masai people do come into conflict with elephants, and this suggests that animals have adapted to specifically listen for and avoid them.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

There is more here.

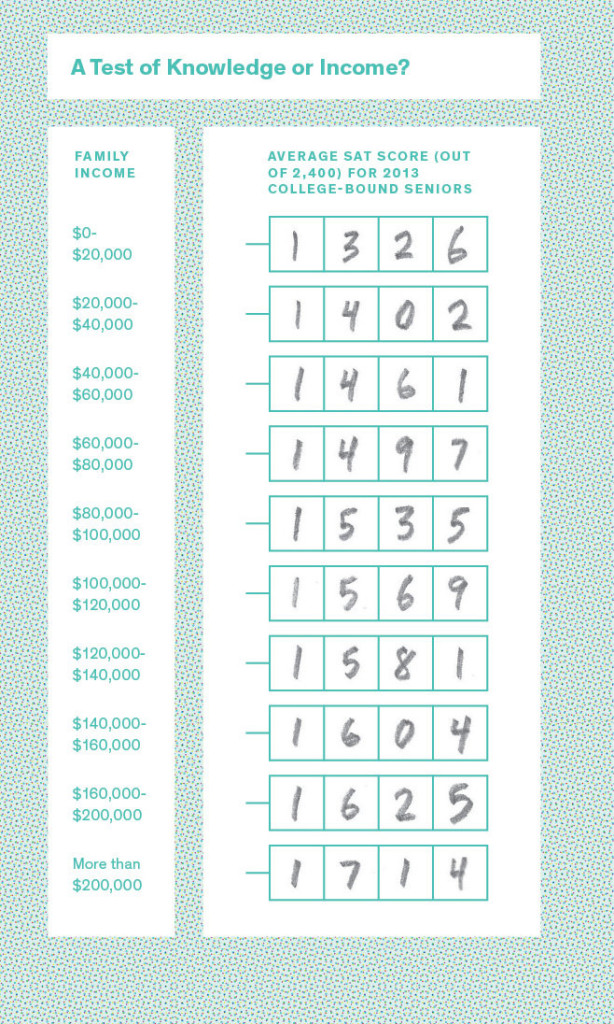

The SAT, Test Prep, Income and Race

The announcement of the new, new SAT has created a lot of hand-wringing about SAT scores and their correlations with income and also race. Wonkblog, the New York Times and many others all feature a table or chart showing how SAT scores increase with income. Wonkblog says these charts “show how the SAT  favors rich, educated families,” and the NYTimes says about the SAT, “A Test of Knowledge or Income?” The consensus explanation for these “shocking” results is the evil of test prep as summarized by NBCNews:

favors rich, educated families,” and the NYTimes says about the SAT, “A Test of Knowledge or Income?” The consensus explanation for these “shocking” results is the evil of test prep as summarized by NBCNews:

…there is also mounting criticism as to whether students who can afford expensive SAT test preparation courses have an unfair advantage, especially given a strong correlation between family income level and test results.

Similarly, Chris Hayes blames test prep for inequality:

We’ve had…the growth of this tremendous testing and test prep industry in New York, along with the massive rise in inequality and it has produced a system in which the school is now admitting only three, four, five black and Latino students. The students they are admitting are almost entirely white, affluent kids with tutors or second generation, first generation immigrants from Queens and other places where the parents pay for test prep. You end up with a system where who you are really letting in are the kids with access to test prep, the kids with access to resources.

All of this is almost entirely at variance with three facts, all of which are well known among education researchers.

First, test prep has only a modest effect on test scores, on the order of 20-40 points combined for a commercial test preparation service. More expensive services such as a private tutor are towards the high of this range, cheaper sources such as a high-school course towards the lower. Buchmann et al., for example, estimate that private tutors increase scores by 37 points while a high school course increases scores by 26 points.

The average SAT score among those with a family income of $20,000-$40,000 is 1402 while the average score among those with an income $100,000 higher, $120,000-$140,000, is 1581 for a 179 point difference. Even if every rich family had a private tutor and none of the poor families had any test prep whatsoever, test prep would explain only 20% of the difference 37/179. If rich families rely on tutors and poor families rely on high school courses, the difference in test prep would explain only 6% (11/179) of the difference in score.

The second surprising fact about test prep is that it doesn’t vary nearly as much by income as people imagine. In fact, some studies find no effect of income on test prep use while others find a positive but modest effect. The latter study finding (what I call) a modest effect finds that in their sample a 2-standard deviation increase in income above the mean increases the probability of using a private test prep course less than whether “Parent encouraged student to prep for SAT (yes or no).”

Since test prep differs by income only modestly and since test prep increases scores only modestly, the effect of income on test scores through test prep is small, Modest*Modest=Small. Contrary to the consensus, test prep can in no way account for the large differences in SAT score by income.

The third fact is that test prep varies by race in the opposite way that people imagine. In the quote above, Chris Hayes suggests that whites use test prep much more than blacks. In fact, blacks use test prep more than whites, as is well documented among education researchers (e.g. here, here, here), e.g. from the first link:

…blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites from comparable backgrounds to utilize test preparation. The black-white gap is especially pronounced in the use of high school courses, private courses and private tutors.

Indeed, since blacks use test prep more than whites and blacks have lower SAT scores than whites the effect of test prep is to reduce not increase the black-white gap in scores. Of course, the net reduction in the gap is small.

Summers, Lomborg, Tabarrok, and Cowen on climate change

There was a brief symposium, here are the results:

Larry Summers

President Emeritus of Harvard University, Former Chief Economist of the World Bank

My sense is that cap and trade is not the route to the future. It did not make it politically in the US at a moment of great opportunity in 2009. And European carbon markets have been plagued by constant problems. And globally it’s even harder. My sense is that the right strategy has three major elements. First, as the G20 vowed in 2009, there needs to be a concerted phase out of fossil fuel subsidies. This would help government budgets, drive increases in economic efficiency and substantially reduce global emissions. Second, there needs to be assurance of adequate funding for all areas of basic energy research. As a practical matter my guess is the world will produce non fossil fuel power in the next 25 years at today s fossil fuel prices or it will fail with respect to global climate change. Third, there is a strong case for concerted carbon taxes to further discourage greenhouse gas emissions. But this is a follow-on step for after the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies.

Bjorn Lomborg

Director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center and adjunct professor at Copenhagen Business School

The only way to move towards a long-term reduction in emissions is if green energy becomes much cheaper. If it cost less than fossil fuels, everyone would switch, including the Chinese. This, of course, requires breakthroughs in green technologies and much more innovation.

At the Copenhagen Consensus on Climate (fixtheclimate.com), a panel of economists, including three Nobel laureates, found that the best long-term strategy to tackle global warming was to increase dramatically investment in green research and development. They suggested doing so 10-fold to $100bn a year globally. This would equal 0.2% of global GDP. Compare this to the EU’s climate policies, which cost $280 billion a year but reduce temperatures by a trivial 0.1 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century.

Alex Tabarrok

Bartley J. Madden Chair in Economics at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University

Neither the developed nor the developing world will accept large reductions in their standard of living. As a result, the only solution to global climate change is innovations in green technology. A carbon tax will induce innovation as people demand a way to avoid the tax. A carbon tax, however, will be more politically acceptable if technologies to avoid the tax are in existence before the tax is put into place. Prizes for green innovations can blaze a path down a road that must be traveled, making the trip easier. The L-prize successfully induced innovation in LED technologies, the X-Prize put a spacecraft into near space twice within two weeks and Google’s Lunar X prize for putting a robot on the moon is close to being awarded. Prizes have proven their worth. To speed both the creation and diffusion of green technology, green prizes should be awarded at the rate of $100-$200 million annually.

Tyler Cowen

Professor of Economics, George Mason University

This is a problem we are failing to solve. Keep in mind it is not just about getting the wealthy countries to switch to greener technologies, but we also desire that emerging economies will find green technology more profitable than dirty coal. A carbon tax is one way forward but the odds are that will not be enough and besides many countries are unlikely to adopt one anytime soon. Subsidies for technology could occur at a very basic level and we could make a gamble that nuclear fusion will finally pay off. We also need a version of green technology that will fit into existing energy infrastructures and into countries which do not have the most reliable institutions. The most likely scenario is that we will find out just how bad the climate change problem is slated to be.

There are further responses at the link.

Addendum: Ashok Rao adds comments.

Is the recent economic growth of Texas driven mainly by fracking?

Scott Sumner reports:

So the Texas oil boom was quite recent, beginning about 2010. Now let’s look at the population growth figures before and after the recent boom:

2005-06: 2.55%

2006-07: 2.01%

2007-08: 2.02%

2008-09: 2.02%

2009-10: 1.85%

2010-11: 1.62%

2011-12: 1.52%

2012-13: 1.50%

Where is all the population growth from fracking?

And this:

Texas’s population grew at roughly twice the national rate for decade after decade, even as oil output was declining sharply.

The post makes several other points of interest. I would stress that Texas has developed at least five highly successful urban clusters, namely Houston, Dallas-Forth Worth, San Antonio, Austin, and to some extent El Paso or I would say El Paso-Juarez. For standard reasons of economic geography, such clusters are especially like in a larger state. Furthermore such clusters can be driven, in part, by relatively small differences in underlying state policy. Maybe Texas policy is only a little bit better than in some other states, but that small underlying difference can translate into a big change in final outcomes. Fracking is likely a complementary force here, but it is not the center of the story.

Assorted links

1. Is internal devaluation boosting Greek exports much?

2. In praise of the London Review of Books. And updated economics on the NYT paywall.

3. The NIH is culling the number of labs it supports.

5. The new Summers version of the secular stagnation argument doesn’t seem to rely on negative natural rates of interest. That said, it is getting closer to a supply-side version of the view.

Is Abenomics working?

Japan’s economy grew by 0.7% in 2013, down from an initial estimate of 1%.

…Japan’s trade gap also rose to a new record last month, increasing by 71% to 2.79tn yen in January, official figures showed.

There is more here, via R. Lopez. For background and context, see Edward Hugh’s recent post.

Addendum: Scott Sumner adds comments.

The Great Divide over Market Efficiency

Clifford Asness and John Liew have an excellent piece in Institutional Investor on Fama, Shiller and The Great Divide over Market Efficiency. Asness and Liew are both students of Fama so you might expect them to come down squarely on the side of market efficiency but they are also co-founders of AQR Capital, an asset management firm ($100 billion under management) with an unusually empirically driven approach to investing. In addition to publishing and using its own research, for example, AQR sponsors the AQR Insight Award which:

…recognizes important, unpublished papers that provide the most significant, new practical insights for tax-exempt institutional or taxable investor portfolios.

The Insight award is worth up to $100,000 so the firm is serious in thinking that research can be profitable.

Asness and Liew argue that just a few anomalies are robust across time, countries, and asset markets, notably momentum and value. On value, they note that a trading strategy of high minus low, that is long a portfolio of cheap stocks (high book value to price) and short a portfolio of expensive stocks (low book value to price) has generated consistently high returns relative to (CAPM) risk over time, albeit not without occasional terrifying episodes.

The efficient market explanation is that book value to price is a stand-in for a non-diversifiable risk factor. The behavioral story is that “a lot of individuals and groups (particularly committees) have a strong tendency to rely on three-to five-year performance evaluation horizons.” As a result, they chase “winners” and flee “losers” over a 3-5 year horizon which generates momentum and the mispricing that makes the value strategy successful. As Asness and Liew put it “investors act like momentum traders over a value time horizon.”

Asness and Liew then follow up with a very astute counter-argument to the risk-factor story:

Also, many practitioners offer value-tilted products and long-short products that go long value stocks and short growth stocks. But if value works because of risk, there should be a market for people who want the opposite. That is, real risk has to hurt. People should want insurance against things like that. Some should desire to give up return to lower their exposure to this risk. However, we know of nobody offering the systematic opposite product (long expensive, short cheap)…the complete lack of such products is a bit vexing for the pure rational based risk-based story.

Lots of other history and insights.

Sweden fact of the day, and the high costs of cash

Stockholm’s homeless population recently began accepting card payments.

The article is more generally about the high costs of cash payments and also storing cash:

In the US, a study by Tufts University concluded that the cost of using cash amounts to around $200 billion per year – about $637 per person. This is primarily the costs associated with collecting, sorting and transporting all that money, but also includes trivial expenses like ATM fees. Incidentally, the study also found that the average American wastes five and a half hours per year withdrawing cash from ATMs; just one of the many inconvenient aspects of hard currency.

Russia and Ukraine facts of the day

The World Bank lists Russia at $14,037 per capita income.

That same source lists Ukraine at $3,867.

Russian per capita income is slightly more than 3.6 times higher. I am not suggesting that Crimea will now experience an economic boom, but this differential is worth keeping in mind as the issue unfolds.

Admittedly the Russian incomes are distributed quite inequitably (Gini of 40 compared to 26 for Ukraine), which lowers the attraction of belonging to that country.

*Massacre in Malaya*

The author is Christopher Hale and the subtitle is the rather misleading Exposing Britain’s My Lai.

The first fifth of this book is in fact the best short early economic history of Malaysia and Singapore I know, even though the focus of the book as a whole is on one colonial event, namely the 1948 Batang Kali massacre during the post-war Malayan Emergency. The next section is a superb treatment of the Japanese occupation and the political issues leading up to that occupation. This book reflects a common principle, namely that often, to learn a topic, you should read a book on an adjacent but related topic, rather than pursue your preferred topic directly. The book on the adjacent topic often will take less background knowledge for granted and explain the context more clearly for what you actually wish to learn, while getting you interested in other topics along the way.

Just about every page of this book has useful and interesting information, here is one new word I learned:

The history of the ‘Malay World’ in the centuries before the momentous fall of Malacca to the Portuguese in 1511 is predominantly a convoluted narrative of maritime statelets, technically thalassocracies.

This one will make my best non-fiction of the year list.