Month: May 2014

Assorted links

Does speaking a foreign language make us more utilitarian?

Albert Costa et.al. say yes:

Should you sacrifice one man to save five? Whatever your answer, it should not depend on whether you were asked the question in your native language or a foreign tongue so long as you understood the problem. And yet here we report evidence that people using a foreign language make substantially more utilitarian decisions when faced with such moral dilemmas. We argue that this stems from the reduced emotional response elicited by the foreign language, consequently reducing the impact of intuitive emotional concerns. In general, we suggest that the increased psychological distance of using a foreign language induces utilitarianism. This shows that moral judgments can be heavily affected by an orthogonal property to moral principles, and importantly, one that is relevant to hundreds of millions of individuals on a daily basis.

The Plos paper is here, hat tip from Vic Sarjoo. And here is another Robin Hanson post on “near vs. far.”

*Anarchy Unbound: Why Self-Governance Works Better Than You Think*

That is the new, forthcoming Peter Leeson book, available here.

Do social problems cause economic problems, or vice versa?

Some discussions stemming from Charles Murray and Paul Krugman raised this perennial issue a while ago. Some on the right suggest that economic struggles of middle class to lower class males (and females) stem from the social dysfunctionality of some of those males. An alternative view is that the lack of good jobs for such men is driving the social problems. Over at The Upshot, David Leonhardt reports on some recent evidence:

The behavior gap between rich and poor children, starting at very early ages, is now a well-known piece of social science. Entering kindergarten, high-income children not only know more words and can read better than poorer children but they also have longer attention spans, better-controlled tempers and more sensitivity to other children.

All of which makes the comparisons between boys and girls in the same categories fairly striking: The gap in behavioral skills between young girls and boys is even bigger than the gap between rich and poor.

By kindergarten, girls are substantially more attentive, better behaved, more sensitive, more persistent, more flexible and more independent than boys, according to a new paper from Third Way, a Washington research group. The gap grows over the course of elementary school and feeds into academic gaps between the sexes. By eighth grade, 48 percent of girls receive a mix of A’s and B’s or better. Only 31 percent of boys do.

I say if the problem has started that early, the social issues are unlikely to be purely derivative of the economic issues.

Aaron Hedlund on Piketty

He writes me in an email:

I feel comfortable saying that his extensive documentation of inequality– it’s trends, composition, etc.– is a big contribution that should drive future research.

…the thesis that r > g is the explanation for inequality or an ominous predictor of future inequality is, to be blunt, ridiculous.

1) Consider the most basic economic growth model: the Solow model where households arbitrarily follow a constant savings rate rule. In that model, the long-run growth rate equals the rate of technological progress, and the rate of return to capital is constant and completely independent of that growth rate. Therefore, you could have r > g, r = g, or r < g, simply because there is NO relationship. In that model, the capital/output ratio is stable in the long-run, again regardless of what r is relative to g.

We could beef the model up a bit by allowing households to actively choose how much to save (rather than impose a constant savings rate rule on them). In that model, the economy will also get to a point with stable long-term growth where the growth rate is determined purely by technological progress. In that model under log utility, 1 + r = (1 + g)*(1 + rate of time preference). As long as people are at all impatient, the implication is r > g. Therefore, the economy will have r > g, stable growth, and a stable K/Y ratio.

The flaw with both of these models, of course, is that they are representative household models where there is no inequality. Therefore, we can go a step further and add uninsurable risk to the model (whether that be health risk, earnings risk, or any other important source of economic risk). In *these* models, households also engage in precautionary savings, so in equilibrium r is lower than it is in the rep agent models. In fact, the greater amount of risk, the more wealth inequality and the SMALLER the gap between r and g.

2) Another huge fallacy is to translate “r > g” as “the return to capital is greater than the rate of return to labor.” The notion “rate of return” indicates an intertemporal dimension: for example, if I invest $1, how much do I get back in return a year later? The growth rate of the economy is not the return to labor. In fact, the “return” to labor is static: I give up x units of time in exchange for y dollars.

The RELEVANT comparison would be to compare the rate of return on capital to the rate of return on investing in human capital (ie you go to college and then reap labor market rewards in the future). The rate of return on human capital is most definitely not just “g.” In fact, the college premium is at an all-time high, which suggests that the rate of return on human capital is quite high and very possibly higher than the rate of return on physical capital.

3) The r > g –> inequality thesis is also based on ignoring the fact that r and g are both determined in equilibrium. Here’s what I mean: it is bad economics to say “Look, r > g, therefore IF people behave in such and such manner, their wealth will grow at a higher rate than g indefinitely.” The reason it is bad economics is because you can’t take the “r > g” as given and THEN impose whatever behavioral assumptions you want. The fact is, people’s behavior affects r and g. In the heterogeneous models I mentioned above, r > g, inequality is STABLE, and the behavior of households is determined by their desire to maximize utility. If I were to go to the model and arbitrarily force the households to behave differently, then the equilibrium r would change.

Here is Hedlund’s home page.

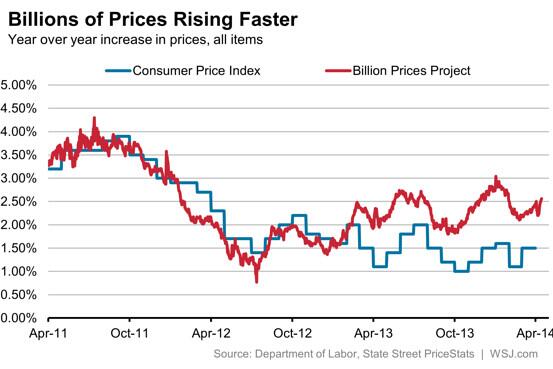

What is the Billion Prices Project showing us about inflation?

The Twitter source is here. I would stress this is speculative, and I am not trying to argue we should panic about higher inflation. I do, however, take this as additional evidence against the view that these days lack of nominal aggregate demand is a major problem.

Assorted links

Is China now the world’s largest economy?

Christopher Ingraham at The Washington Post has a good short piece on this:

Is China’s economy really set to overtake the United States this year, as manynewsoutletsreported Wednesday morning? Not exactly.

Those headlines come from a new World Bank report that looks at the purchasing power parities (PPP) of world economies. It’s a way of standardizing GDPs across different currencies and economies by “the number of units of a country’s currency required to buy the same amounts of goods and services in the domestic market as U.S. dollar would buy in the United States,” according to the Bank’s definition.

On that measure, China is looking pretty good. As of 2011 (the latest year data are available), its GDP stood at about 87 percent of the U.S. GDP, or 15 percent of the world’s total economic output. This is a huge increase from 2005, when China’s economy was less than half the size of ours.

But there’s a reason that standard measures of GDP don’t use the PPP conversion. As the Wall Street Journal’s Tom Wright explains:

“China can’t buy missiles and ships and iPhones and German cars in PPP currency. They have to pay at prevailing exchange rates. That’s why exchange rate valuations are seen as more important when comparing the power of nations.”

Standard GDP measures take these exchange factors into account. And here, China is doing about as well as one would expect. They’re still the world’s second-largest economy, but their GDP is less than half the size of the U.S. GDP.

This piece is also a good example of just how much economics and financial journalism has improved, post-blogosphere.

The wisdom of Scott Sumner

Some on the left argue that consumption taxes will favor the ultra-rich because they consume a very small share of their income. But if that’s so, then no tax regime will put much of a tax burden on the ultra-rich. Just as you can’t squeeze blood from a stone, you can’t put a tax burden on misers. As Steven Landsburg pointed out in one of my all time favorite posts, society views misers like Scrooge as being selfish individuals, when actually it’s people who consume a lot who are selfish. Misers leave more for others to consume.

In my only slightly cynical view, a lot of the debate about taxation is more about showing the wealthy that they need to lose (or win, on the other side of the debate) a few political battles than it is about actual canons of efficiency or for that matter even well-specified theories of egalitarian justice. For instance I find that few proponents of a higher inheritance tax realize it will increase current consumption inequality, by encouraging the wealthy to consume more rather than paying the tax. Nor do they seem to care, once this is pointed out. I call this “the comeuppance” theory” and it is another example of Robin Hanson’s motto that “politics isn’t about policy,” but rather is a spat about which monkeys should have a higher or lower status.

Scott’s post is here, and it contains other points of interest.

Not what I expected from the culture that is Japan

In a bid to be more globally competitive and raise the level of English education in the country, the Japanese Ministry of Education will soon begin conducting their meetings in the language. As using English in meetings is highly unusual in the country, the ministry will start implementing it slowly, beginning with high-level officials in their department.

To help them with this, the ministry has sought for an English Education Project Officer that will be in charge of coming up with strategies and plans pertaining to English education. The post, though on a part-time basis, would require someone who has taken an English proficiency test called TOEIC with a score of at least 800. The ministry has chosen a candidate who was successful in integrating the English language as a corporate official language to a private company, and will stay with the ministry for a one-year contract. The English Education Project Officer will join top-level meetings within the ministry to assess their capability and suggest improvements. An official from the Education Ministry said, “By using English among ourselves, we hope we will be able to broaden our perspectives on English education.”

The story is here, via the excellent Mark Thorson.