Month: May 2014

Is Piketty’s “Second Law of Capitalism” fundamental?

Per Krusell and Tony Smith have a new paper on Piketty (pdf), which I take to be reflecting a crystallization of opinion on the theory side. Here is one excerpt:

There are no errors in the formula Piketty uses, and it is actually consistent with the very earliest formulations of the neoclassical growth model, but it is not consistent with the textbook model as it is generally understood by macroeconomists. An important purpose of this note is precisely to relate Piketty’s theory to the textbook theory. Those of you with standard modern training have probably already noticed the difference between Piketty’s equation and the textbook version that we are used to. In the textbook model, the capital-to-income ratio is not s=g but rather s/(g+ δ), where δ is the rate at which capital depreciates. With the textbook formula, growth approaching zero would increase the capital-output ratio but only very marginally; when growth falls all the way to zero, the denominator would not go to zero but instead would go from, say 0.12—with g around 0.02 and δ = 0.1 as reasonable estimates—to 0.1. As it turns out, however, the two formulas are not inconsistent because Piketty defines his variables, such as income, y, not as the gross income (i.e., GDP) that appears in the textbook model but rather as income, i.e., income net of depreciation. Similarly, the saving rate that appears in the second law is not the gross saving rate as in the textbook model but instead what Piketty calls the “net saving rate”, i.e., the ratio of net saving to net income.

Contrary to what Piketty suggests in his book and papers, this distinction between net and gross variables is quite crucial for his interpretation of the second law when the growth rate falls towards zero. This turns out to be a subtle point, because on an economy’s balanced growth path, for any positive growth rate g, one can map any net saving rate into a gross saving rate, and vice versa, without changing the behavior of capital accumulation. The range of net saving rates constructed from gross saving rates, however, shrinks to zero as g goes to zero: at g = 0, the net saving rate has to be zero no matter what the gross rate is, as long as it is less than 100%. Conversely, if a positive net saving rate is maintained as g goes to zero, the gross rate has to be 100%. Thus, at g = 0, either the net rate is 0 or the gross rate is 100%. As a theory of saving, we maintain that the former is fully plausible whereas the latter is all but plausible.

With the upshot coming just a wee bit later:

…Moreover, whether one uses the textbook assumption of a historically plausible 30% saving rate or an optimizing rate, when growth falls drastically—say, from 2% to 1% or even all the way to zero—then the capital-to-income ratio, the centerpiece of Piketty’s analysis of capitalism, does not explode but rather increases only modestly. In conclusion, at least from the perspective of the theory that we are more used to and find more a priori plausible, the second law of capitalism turns out to be neither alarming nor worrisome, and Piketty’s argument that the capital-to-income ratio is poised to skyrocket does not seem well-founded. [emphasis added by TC]

Krusell and Smith really know their stuff on this topic and their arguments to me seem completely correct.

By the way, here is a Chris Giles follow-up post from The FT, very useful.

Assorted links

1. The evolution of chess openings. Chess openings have become more diverse over time.

2. Modular robots that double as furniture.

3. Piketty responds (again) to the FT. And AFineTheorem on Piketty. And knowhow, dark matter, and Piketty’s capital, from Ricardo Hausmann. And me on Piketty on the radio, transcript.

4. Where to look for your lost mother.

5. Safety vest for chickens (there is no great stagnation). And temporary tattoos hold cooking recipes for ready scrutiny.

6. Amazon responds on Hachette.

Individual NBA players hire statisticians

When will we all?:

Zormelo, who works for individual players and not their teams studies film, pores over metrics, and feeds his clients a mix of information and instruction that is as much informed by Excel spreadsheets as it is by coaches’ playbooks. He gives players data and advice on obscure points of the game — something many coaches may not appreciate — like their offensive production when they take two dribbles instead of four and their shooting percentages when coming off screens at the left elbow of the court.

There is more here, via @EdwardGarnett. Kevin Durant and John Wall are two of his better-known employers. The NBA coaches, by the way, are not necessarily informed about Zormelo’s work.

More cars, fewer pedestrian deaths

Michael Blastland and David Spiegelhalter have a new book about risk — The Norm Chronicles: Stories and Numbers About Dangers and Death — and it does actually have new material on what is by now a somewhat worn out topic. Here is one example:

In 1951 there were fewer than 4 million registered vehicles on the roads in Britain. They meandered the highways free of restrictions such as road markings, traffic calming, certificates for roadworthiness, or low-impact bumpers. Children played in the streets and walked to school. The result was that 907 children under 15 were killed on the roads in 1951, including 707 pedestrians and 130 cyclists. Even this was less than the 1,400 a year killed before the war.

The carnage had dropped to 533 child deaths in 1995, to 124 in 2008, to 81 in 2009, and in 2010 to 55 — each a tragedy for the family, but still a staggering 90 percent fall over 60 years.

You can buy the book here.

*Age of Ambition*, by Evan Osnos

This is one of the best books on contemporary China, maybe the best. The subtitle is Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China. Osnos is the former New Yorker correspondent in the country for five years up through 2013. Here is one excerpt:

Li routinely taught in arenas, to classes of ten thousand people or more. The most ardent fans paid for a “diamond degree” ticket, which included bonus small-group sessions with the great man. The list price was $250 a day — more than a full month’s wages for the average Chinese worker. Students thronged him for autographs. On occasion, they sent love letters, wrapped around undergarments.

There was another widespread view of Li’s work. “The jury is still out on whether he actually helps people learn English,” Bob Adamson, an English-language specialist at the Hong Kong Institute of Education, told me. Li’s patented brand of shouting occupied a specific register: to my ear, it was not quite the shriek reserved for alerting someone to an oncoming truck, but it was more urgent than a summons to the dinner table. He favored flamboyantly patriotic slogans such as “Conquer English to Make China Stronger!” On his website, he declared, “America, England,Japan — they don’t want China to be big and powerful! What they want most is for China’s youth to have long hair, wear bizarre clothes, drink soda, listen to Western music, have no fighting spirit, love pleasure and comfort! The more China’s youth degenerated, the happier they are!”

Definitely recommended, fascinating throughout.

*American Railroads* (arrived on my desk)

The subtitle is Decline and Renaissance in the Twentieth Century, and the authors are Robert E. Gallamore and John R. Meyer. John Meyer passed away in 2009 and this volume is a finished version of his last major work.

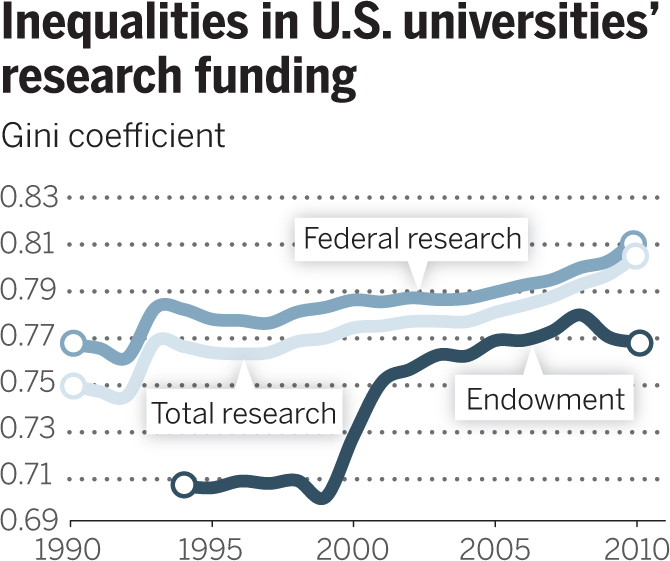

Gini coefficient for U.S. universities

For the pointer I thank J.O.

Assorted links

1. Clever birds figure out automatic door.

2. Japanese book on how to use profanity correctly in English. And other methods of Japanese quality improvement.

3. Entropy and inequality (speculative, possibly downright dubious).

4. Why the European left is collapsing (speculative and overblown, but also makes some good points).

5. Why restitution should be small (a 2002 essay by me).

6. “Let’s, Like, Demolish Laundry.”

7. More Galbraith on Piketty. Nate Silver on Piketty and data.

8. And very very sadly the Mackintosh library in Glasgow has been destroyed by fire.

Underreported good news

Pakistan’s prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, met on Tuesday with his new Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, in a swiftly arranged bilateral session that caught many by surprise and offered some hope that the two countries may resume a tentative peace process after a year and a half of frosty silence.

Why has French employment (for some workers) done so well?

Paul Krugman has an interesting column which focuses on some too often ignored facts about labor markets, here is one excerpt:

France’s prime-age employment rate overtook America’s early in the Bush administration; at this point the gap in employment rates is bigger than it was in the late 1990s, this time in France’s favor.

There is of course more to the column than that. In terms of the bigger picture, I read Krugman as trying to argue this shows more interventionism doesn’t have to be bad. A closer look at the French labor market experience, however, suggests a somewhat different perspective. Here are a few points:

1. In France the influence of less regulated short-term jobs has been rising in importance. For instance “the share of STJ [short-term jobs] in total inflows from unemployment to employment is around 69 per cent,” circa 2010, see p. 7 (pdf). Changes in temporary jobs have driven the French employment picture since 2000 (p.8). That is the French version of The Great Reset and it does not bode well. Very few French think their children will be able to enjoy the same standard of living as they have.

2. The International Labour Organisation — not exactly The Heritage Foundation — writes about France: “The extensive recourse to short term jobs (STJ) is a striking feature of labour markets with stringent employment protection.” (p.20)

3. Favorable French employment results are also due to labor supply effects. For some classes of French workers, especially at the lower end, the return to working has remained high relative to alternative opportunities. Card, Kramarz and Lemieux (pdf) noted this as early as the mid-1990s and also cited a 1992 paper to this effect (see p.870). The United States in contrast has a larger share of jobs which pay quite a bit less than the median wage and not everyone wishes to take those jobs. The evidence here supports some of the “relative wage” theories, where your willingness to work is determined by broader social norms for what a job should go for, rather than just the absolute wage. It is also possible that lower-earning Americans have a weaker work ethic than do the French.

4. To the extent the supply side is the binding constraint, some labor market rigidities won’t hurt employment very much.

5. Even after some massive aggregate demand shocks to both countries, which the USA clearly had a superior response to, the supply side forces still play a positive role in French labor market outcomes. That is against the tenor of other opinions Krugman has expressed about employment being solely demand-driven these days. The supply side of labor markets never ceases to matter, even if it does not always matter in the way that conservative economists are claiming.

6. Within France, there is still plenty of evidence (pdf) that interventions such as the minimum wage bring classic negative effects on employment, even if this is overwhelmed by other factors in some cross-national comparisons.

7. The French system has a much poorer record of employment for the young and for the old, so focusing on prime age workers, while valuable, also doesn’t show the whole picture. For instance French seniors participate in the labor force at 42.5% compared to 72.6% for Sweden, a huge gap. And that artificial removal from so many of the elderly from the labor force in part props up real wages for the prime-age workers. It isn’t as good a deal as it looks if you focus on the prime age workers only.

8. French youth unemployment is quite bad, and contrary to what Krugman seems to suggest it is not mainly because the French are all getting so well-educated. Degree holders are getting stuck too and that is part of the French “Great Reset.”

9. A major ongoing problem for the French labor market is that net public sector job creation hasn’t been there since 2000. That is unlikely to change moving forward and will probably get worse, given French fiscal constraints. This is not something to blame on “austerity,” the French really are close to their fiscal limits.

10. The large number of protected jobs in France has come at a significant growth and efficiency cost: “Until the 1990s, France was among Europe’s leading economies in per capita GDP. By 2010, however, the country had dropped to 11th out of the EU-15.”

11. Here is an interesting comparison between Spanish and French labor market responses to the downturn, although the housing bubble in Spain should play a more prominent role in the argument. You really can read French policy as determined to protect good jobs for prime age workers, at all costs if need be.

For general background, here is a broader Nickell JEP 1997 piece on European vs. U.S. labor markets. If anything, Krugman’s basic observation has been correct for longer than he is letting on.

The worst book blurb I have read

Get this:

“The written equivalent of a Botticelli.”

That is from an advertisement for Antony Doerr’s All The Light We Cannot See.

The book has stellar Amazon reviews, and the MSM reviews are quite positive (or here), and yet I bought it only with reluctance, more to satisfy my curiosity than because I think I will enjoy or finish it.

What exactly is so bad about that blurb? After all, I like Botticelli. I like Botticelli a lot. But if they are targeting readers who think such a book can be compared meaningfully to Botticelli, or who would be impressed by such a designation…then I start to worry. And that one piece of Bayesian information weighs more heavily in my mind than all the praise for the work I have encountered.

Assorted links

Very good sentences to ponder

Markets in everything the packing culture that is New York

The division of labor is indeed limited by the extent of the market:

New York City mommies with money to burn are hiring professional organizers to pack their kids’ trunks for summer camp — because their darlings can’t live without their 1,000-thread-count sheets.

Barbara Reich of Resourceful Consultants says she and other high-paid neat freaks have been inundated with requests — and the job is no small feat.

It takes three to four hours to pack for clients who demand that she fit all of the comforts of home in the luggage, including delicate touches like French-milled soaps and scented candles.

At $250 an hour, the cost for a well-packed kid can run $1,000.

There is more here, via the excellent Mark Thorson.

Nurses complain about algorithms

In response [to the rise of diagnostic algorithms], NNU [National Nurses United] has launched a major campaign featuring radio ads from coast to coast, video, social media, legislation, rallies, and a call to the public to act, with a simple theme – “when it matters most, insist on a registered nurse.” The ads were created by North Woods Advertising and produced by Fortaleza Films/Los Angeles. Additional background can be found at http://www.insistonanrn.org.

Here is the link. Here is an MP3 of the ad. Remarkable, do give it a listen. It has numerous excellent lines such as “Algorithms are simple mathematical formulas that nobody understands.”

For the pointer I thank Eric Jonas.