Month: June 2014

Arrived in my pile

Ignacio Palacios-Huerta, Beautiful Game Theory: How Soccer Can Help Economics.

Pierre Michel-Menger, The Economics of Creativity: Art and Achievement Under Uncertainty.

Austin Frakt and Mike Piper, Microeconomics Made Simple: Basic Microeconomic Principles Explained in 100 Pages or Less.

Daniel W. Drezner, The System Worked: How the World Stopped Another Great Depression.

Assorted links

Very good Larry Summers FT review of Mian and Sufi

It is here, he mostly really likes the book but thinks they are not sophisticated enough in their policy prescriptions. Here is one good excerpt on whether the federal government should have worked harder to institute mortgage cramdowns:

First, there was the risk of bringing down the system in an effort to save it. Banks had substantial mortgage holdings and especially large quantities of subordinated second mortgages and home equity lines of credit, which would have been wiped out if mortgage principal had been reduced in a way that respected the seniority of first mortgages. We recognised that large-scale principal reduction would draw in a large number of mortgages that were not delinquent and would otherwise be paid in full. As a consequence, there was the risk of sucking hundreds of billions of dollars out of the banking system. Given that government funds for capital infusions were scarce and that each dollar of bank capital supports $12 of lending, we worried that the spending gains from reducing mortgage debt might well be exceeded by the spending losses from reducing the flow of capital. This fear may have been exaggerated. If they think so, Mian and Sufi owe an explanation as to why.

Second, there was the issue of chilling future lending… This was not a small concern, as the automobile industry was in freefall and consumer confidence was deteriorating very rapidly.

Third, there was the danger of prolonging the housing market’s problems. Even the relatively limited programmes in place have spent as much as a third of their money delaying, rather than avoiding, foreclosures. All that we heard at the time suggested that a significant part of the reason why the housing market was dead was that no one wanted to buy because of a fear that it had further to fall. Delaying inevitable foreclosures with relief risked exacerbating this problem and risked larger foreclosure discounts when houses were ultimately sold.

What I’ve been Reading

1. Gendun Chopel, Grains of Gold: Tales of a Cosmopolitan Traveler, introduction by Thupte Jimpa and Donald S. Lopez Jr. A very learned Tibetan scholar travels to India and records his hyper-structured impressions of what is obviously a more modern and economically developed land. Yet India is also the original homeland of Buddhism and as such a source of obsession about the distant past. Brilliantly rendered, the manuscript reads like a source that would have inspired Borges. Every now and then the narrative comes to a full stop and we get a chapter like “How the Lands Were Given Their Names.” Later the manuscript was shipped back by yak, and Chopel was sent to jail in Tibet for having written it. This volume has one of the best introductions of any book I have read. A fantastic look at the culture that was Tibet, or for that matter India or Sri Lanka. Chopel is trying to incorporate modernity into the traditional Tibetan worldview, and yet throughout cannot avoid a sense of the tragic and of decay, which only the book itself is contradicting.

2. Amity Shlaes, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, graphic edition, the illustrations work very well. I have only paged through it.

3. John Sutherland, How to be Well Read: A Guide to 500 Great Novels and a Handful of Literary Curiosities. It is great fun to browse through this work. It is out only in the UK, I found it in Daunt Books, there is always reason to travel to London.

4. Ralph Nader, Unstoppable: The Emerging Left-Right Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State. I am supposed to interview Nader soon, and so I am reading up on his history, he has become an oddly undervalued figure, remembered mainly for his spoiler role in Gore vs. Bush. Here is a piece on Nader’s ostensible “turn to the right,” that is not how I would describe it, as with Krugman I see continuity from a person who is basically a moralizing conservative with a crusading zeal. And who would have thought Nader is a fan of Wilhem Roepke?

5. Alex Wright, Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age. An excellent study of a Belgian, Paul Otlet, who in the late nineteenth century began “a vast intellectual enterprise that attempted to organize and code everything ever published.” He started by expanding the potential of the card catalog and then wished to build a mechanical collective brain known as the Mundaneum, a “Steampunk version of hypertext.” Relevant of course to the origins of the web, Wikipedia, and current sites such as Vox.com. You can read more about Otlet and his infovore tendencies here.

The Georgia Tech online program is going pretty well

Administrators at the Georgia Institute of Technology are optimistic but “not declaring victory” after one semester of its affordable online master’s degree program in computer science. While the program has been well-received by students, administrators are still striving to solve an equation that balances cost, academic quality and support services.

“We’re not all the way there yet, but I couldn’t ask for a much better start,” Zvi Galil, dean of the College of Computing, wrote last month in an email to Georgia Tech faculty on the one-year anniversary of the program’s announcement.

…The buzz around the online degree program appears to have benefited the residential program as well. This year, applications were up by 30 percent, the university reported.

There is more here.

From the comments, on the ECB

Ptumov writes:

First, on the market reaction. This action has been leaked/signaled to the markets in many ways over the last month. Therefore, to judge the market reaction to the ECB action, I think one should look at the change from early May to today.

Second, what’s the difference between non-sterilized SMP and QE? Not much, maybe maturity. I think this was the more significant development moving the market over the past month than negative deposit rates.

Assorted links

1. Godfather markets in everything (“same effect — without the mess”).

2. Bulletproof and fireproof house made of used plastic bottles.

3. Plans for a self-assembling moonhouse.

4. Indian Muslims and the child mortality puzzle.

5. What would negative ECB interest rates mean? And what would you expect from a web site titled RussianOptimism?

The new ECB measures

My perhaps overly simplistic view is that unless some of the various electorates hate the announced measures, they are not enough. An adequate response would be “we are going to raise the rate of price inflation, probably indefinitely, and furthermore countries x, y, and z have agreed they are not getting all of their money back. They agree to pick up the check and their electorates hate this but accept it as well and furthermore all the politicians involved are telling their electorates the same thing that they say amongst themselves. We also accept that weak lending to medium- and small-sized business represents a real competitiveness problem, a kind of Great Reset, and is not amenable to a simple monetary policy fix but we have to do something so we will try anyway.”

Obviously Draghi was in no position to make such an announcement. I once liked the idea of a negative rate on deposits at the central bank, but I no longer do. I think it will represent more of a tax on future lending than a spur to current lending. Denmark once tried such a policy and it didn’t do much for them. It is probably a one-off shot in the new “currency wars” but not a game-changer. In any case total bank deposits held at the ECB are relatively small.

We’ll see what else Draghi announces later today. European stocks are up, so it is hard to argue with this as an improvement over the status quo ex ante, which of course was terrible. Still, I am not as impressed as are many of the people in my Twitter feed.

Depreciating Capital

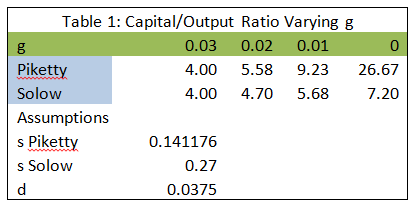

Brad DeLong attacks Krusell and Smith for using in some of their thought experiments a depreciation rate of 10%, which is probably too high. Fair point but in my post I assumed a depreciation of just 5% and showed that Solow and Piketty give very different predictions about how the K/Y ratio will change with a change in g.

Furthermore, having read DeLong’s comment, I went to the BEA and compared gross and net domestic product which gives capital depreciation as a fraction of GDP of around 15% in recent decades. At a K/Y ratio of 4 that’s a depreciation rate of 3.75%. Similarly, Inklaar and Timmer in constructing capital stocks for the Penn World Tables estimate a depreciation rate for the U.S. of 4.1%. I reran my simple Excel chart with the lower number, 3.75%.

As you can see, the numbers are very similar to earlier and the key point is still that a decrease in g increases K/Y much more in the Piketty model than in the Solow model.  Krusell responds to DeLong here making the additional point that their thought experiments show that Piketty’s assumption about savings is implausible at any depreciation rate (see also Hamilton on this point).

Krusell responds to DeLong here making the additional point that their thought experiments show that Piketty’s assumption about savings is implausible at any depreciation rate (see also Hamilton on this point).

First: if the net rate of saving remains positive as the economy’s growth rate falls toward zero, as Piketty assumes in his second fundamental law of capitalism, the gross saving rate in the economy must approach 100%. This observation is a way of illustrating how unreasonable the behavioral assumptions underlying his theory of saving really are.

Second: according to standard, and much more reasonable, saving theory (based either on the standard textbook Solow growth model or on the permanent-income model), the net saving rate must fall with the rate of growth, and become zero when growth is zero.

…These points are key because Piketty’s predictions are all about what happens as growth falls during the 21st century, as he argues it will.

…both of these results hold no matter what the depreciation rate is (so long as it is positive).

The heart of Piketty’s theory is his expression for the capital share of income in the long run, α = r × s/g with the prediction that if g falls the capital share will rise tremendously. This is a good opportunity to summarize some of the recent points about the theory.

There are no contradictions but many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip. Namely, will g fall? If g does fall, will K/Y increase? If K/Y increases will capital’s share of income increase? My answers:

Will g fall? Uncertain. Piketty’s forecast is as good as anyone’s. My own view is that at the global level g has been increasing for several centuries and that this will continue, especially because in this century we will see a massive increase in the number of scientists and engineers as China and then India devote increased human capital to the research frontier.

If g does fall, will K/Y increase? Yes, but probably less than Piketty estimates and more in line with Solow.

If K/Y increases will capital’s share of income increase? Uncertain but more likely no than yes. It depends on the elasticity of substitution between K and L and as Rognlie and Summers argue, the elasticity that Piketty needs is higher than current estimates suggest is the case.

How easily can we eliminate paper currency?

Ken Rogoff says we should do it, Miles Kimball has written extensively on the topic, Willem Buiter too.

But how to do it, assuming that we wanted to? (Here is the piece by Miles which covers the transition most specifically.) Let’s say you allow people to turn in their currency for tickets to heaven and the currency is then never replaced. In the short run that will increase the demand for currency in precisely such a way that advocates of a currency-less economy worry about.

Alternatively, we could tax people caught holding paper currency, either explicitly or implicitly. Imagine for instance random lotteries, based on serial numbers, which make some dollar bills suddenly worthless. People then will try to spend their currency and velocity will increase. But currency doesn’t go away. The policymaker could try to drive up velocity so much so that currency had a value of zero. This either drives up prices a lot, or alternatively currency acquires a price separate from demand deposits and other forms of inside money. The former option seems undesirable, whereas the latter leads to a good outcome. But note this: once currency has a separate price, you don’t need to get rid of it on any macroeconomic grounds. Pricing currency is better and easier than getting rid of it.

Yet another scenario, as Kroszner and I had outlined a long time ago, is for currency to evolve out of existence, as it is slowly displaced by assets of higher return and greater convenience, such as electronic payment media. This does not involve transition problems, but it takes a long time. In recent times currency if anything has been a growing part of the U.S. money supply.

Rogoff suggests eliminating large-denomination notes as a way to start. I don’t object to that suggestion but of course it doesn’t get rid of currency. It even runs the danger that a truly small and squirrely asset — small notes of currency — starts ruling the roost, a’la Keynes’s chapter seventeen.

Once you have currency, it is hard to get rid of in an efficacious way. It is harder yet if you think that currency “rules the roost” in some kind of disadvantageous manner. Getting rid of currency is a discrete event of some kind, and thus it would bring discrete changes to…the roost.

Do black web markets lower the violence associated with drugs?

It seems maybe so, from a new paper by Judith Aldridge and David Décary-Hétu, the abstract is this:

The online cryptomarket Silk Road has been oft-characterised as an ‘eBay for drugs’ with customers drug consumers making personal use-sized purchases. Our research demonstrates that this was not the case. Using a bespoke web crawler, we downloaded all drugs listings on Silk Road in September 2013. We found that a substantial proportion of transactions on Silk Road are best characterised as ‘business-to-business’, with sales in quantities and at prices typical of purchases made by drug dealers sourcing stock. High price-quantity sales generated between 31-45% of revenue, making sales to drug dealers the key Silk Road drugs business. As such, Silk Road was what we refer to as a transformative, as opposed to incremental, criminal innovation. With the key Silk Road customers actually drug dealers sourcing stock for local street operations, we were witnessing a new breed of retail drug dealer, equipped with a technological subcultural capital skill set for sourcing stock. Sales on Silk Road increased from an estimate of $14.4 million in mid 2012 to $89.7 million by our calculations. This is a more than 600% increase in just over a year, demonstrating the demand for this kind of illicit online marketplace. With Silk Road functioning to considerable degree at the wholesale/broker market level, its virtual location should reduce violence, intimidation and territorialism. Results are discussed in terms of the opportunities cryptomarkets provide for criminologists, who have thus far been reluctant to step outside of social surveys and administrative data to access the world of ‘webometric’ and ‘big data’.

Here is a write-up in Wired. For the pointer I thank Andrea Castillo.

The Declining Fortunes of the Young Since 2000

That is a new piece in the May AER by Paul Beaudry, David A. Green, and Benjamin M. Sand, here is the clincher scary paragraph:

The data reveal a clear break in 2000. Between 1992 and 2000, each successive entry cohort has a higher share in cognitive occupations at the outset of their working lives, with the proportion increasing by 0.1 between the 1994 and 1998 cohorts. After 2000, with the exception of the difference between the 2004 and 2006 entry cohorts, each successive cohort has a lower share in these occupations, with the share at entry for the 2010 cohort being approximately the same as for the 1990 cohort. Given all the attention that has been paid to growing demand for cognitive skills, this complete reversal is striking.

Do you know of an ungated version? Here is a related Brookings piece of research (pdf). Here is a related piece by Acemoglu, Auor, Dorn, Hanson, and Price.

Assorted links

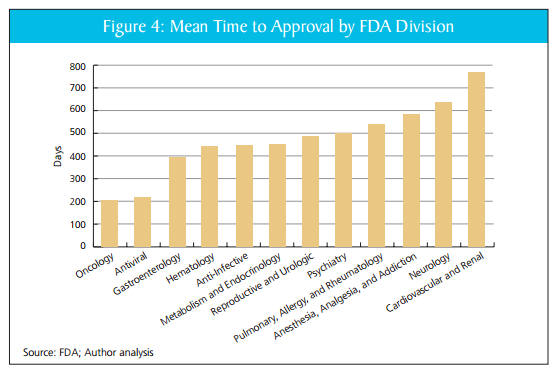

Rating the FDA by Division: Comparison with EMA

Reporters have been asking the FDA about my paper with DiMasi and Milne, AN FDA REPORT CARD. As you may recall, the upshot of that paper is that there is wide variance in the performance of FDA divisions. Here, for example, is the mean time to approval across divisions.

Our simple index, discussed in the paper, suggests that these differences are not easily explained by factors such as resources, complexity of task or differences in safety tradeoffs across divisions. In responding to our paper, however, the FDA has said that similar differences in time to approval by drug type are seen at other drug approval agencies. If true, that would be an important criticism.

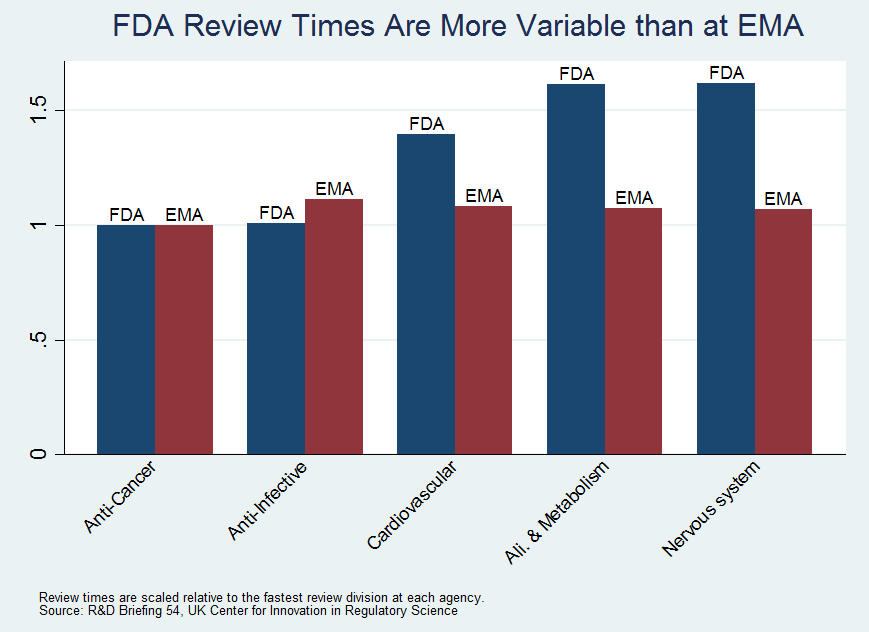

Fortuitously, some relevant data crossed our desk recently. The Center for Innovation in Regulatory Science (CIRS), a UK based research consortium, compared median review times at the FDA to the next most important drug regulatory agency in the world, the European Medicines Agency (they also look at the Japanese agency). To their credit, the FDA is faster on average than the EMA (thanks PDUFA!). What is relevant for our purposes, however, is to compare differences across divisions.

The CIRS breaks drugs into broader classes than we used but the story they tell for the FDA is similar to ours; anti-cancer drugs, for example, are approved much more quickly than neurology drugs. The story for the EMA, however, is very different than for the FDA. For the EMA all types of drugs are approved in roughly the same amount of time.

We have argued that the wide variance in performance at the FDA is suggestive of differences in productivity. The fact that we do not see the same wide variance in performance at the EMA is supportive of our argument. Our goal and conclusion still stand:

We support further study to identify the policies and procedures that are working in high-performing divisions, with the goal of finding ways to apply them in low-performing divisions, thereby improving review speed and efficiency.

A union for prisoners? (the culture that is Germany)

A group of inmates at a prison in Berlin have set up the world’s first union for prisoners, in an attempt to campaign for the introduction of a minimum wage and a pension scheme for convicts.

Inmates at Berlin Tegel jail, where the union is based, work regular shifts in kitchens and workshops, which in the view of the union makes them “de facto employees, just like their colleagues outside the prison gates”.

“Prisoners have never had a lobby working for them. With the prisoners’ union we’ve decided to create one ourselves,”said Oliver Rast, a spokesman for the group.

In Germany, as in Britain, prisoners are excluded from national pension schemes and the national minimum wage, which in Germany’s case is planned to come into effect in 2015 at €8.50 (£6.90) an hour. Inmates at Berlin Tegel earn between €9 and €15 per day, depending on their qualifications.

The Berlin union, which is registered as an association without legal status and claims to have collected numerous signatures within the prison, criticised the exclusion of prisoners from minimum wage plans.

It said the lack of pension schemes meant that many elderly inmates were released straight into poverty.

There is more here, via Mark Thorson.