Month: January 2015

Assorted links

1. How is that higher-order polynomial shaping up?

2. Do academic sociologists discriminate against the poor?

3. Are youth sports one of our biggest signaling problems? They were great for me (Little League especially, seven years), but much cheaper back then.

4. The movie A Most Violent Year is excellent on the creeping nature of corruption, the operation of credit markets, upward mobility and the nature of the American dream, and the New Jersey heartland circa 1981. Here is a good article on it. I liked Selma too.

5. Which are the disproportionately popular ethnic cuisines in each state? They get most states right, but surely Virginia should be El Salvadoran, not Peruvian, unless they miscount some of the more generic Latino chicken places as Peruvian. And “Belgian” for D.C.? I can think of two or three places, although I suspect North Dakota has fewer than that. Most people might guess Ethiopian.

6. Harvard economics exam from 1953, for senior undergraduates.

7. New drone will hunt other drones. And “…domestic criticism of the SNB’s large buildup of exchange-rate reserves (euro assets) was mounting.”

No, A Majority of US Public School Students are Not In Poverty

In widely reported article the Washington Post says a Majority of U.S. public school students are in poverty. The article cites the Southern Education Foundation:

The Southern Education Foundation reports that 51 percent of students in pre-kindergarten through 12th grade in the 2012-2013 school year were eligible for the federal program that provides free and reduced-price lunches.

Eligibility for free and reduced-price lunches, however, depends on eligibility rules and not just income levels let alone poverty rates. The New York Times article on the study is much better:

Children who are eligible for such lunches do not necessarily live in poverty. Subsidized lunches are available to children from families that earn up to $43,568, for a family of four, which is about 185 percent of the federal poverty level.

The number of children eligible for subsidized lunches has probably increased in part because the federal Agriculture Department now allows schools with a majority of low-income students to offer free lunches to all students, regardless of whether they qualify on an individual basis or not.

Frankly I suspect that this study was intended to confuse the media by conflating “low-income” with “below the poverty line”. Indeed, why did this study grab headlines except for the greater than 50% statistic? It is very easy to find official numbers of the number of students in poverty according to the federal poverty standard. Here is what the National Center for Education Statistics says about school-age children and poverty (most recent data):

In 2012, approximately 21 percent of school-age children in the United States were in families living in poverty.

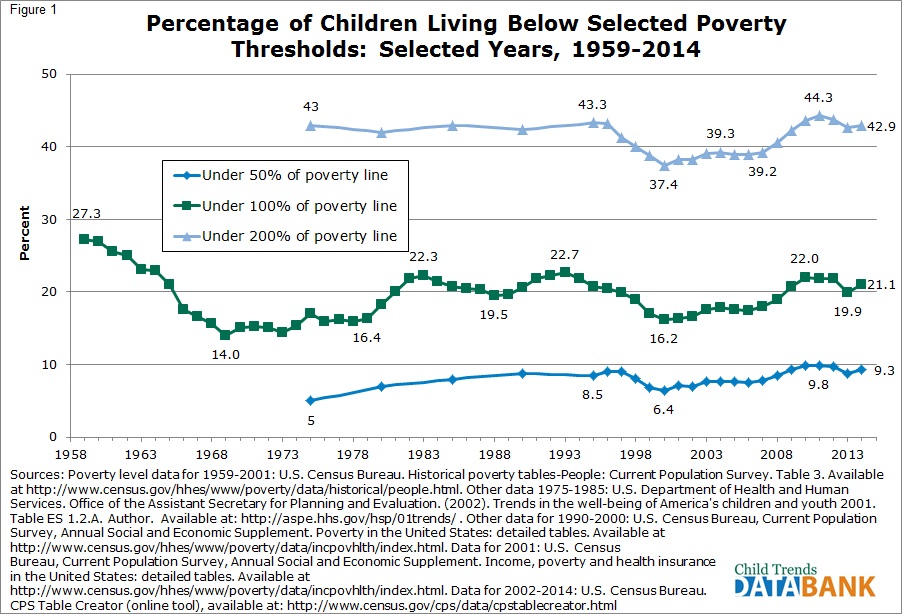

The number of school-age children living in poverty today is relatively high and not surprisingly did increase with the 2008 recession and its aftermath (green line in figure below – the numbers here differ slightly from NCES but the time line is longer). But recent numbers do not look like especially remarkable compared to the history.

It’s certainly worthwhile discussing why poverty has increased. The economy is one possible reason as are issues to do with family formation and marriage rates. Another possibility is immigration. A higher poverty rate caused by the immigration of more low-income children is compatible with everyone becoming better off over time and not necessarily a bad thing. Those are just a few possible topics worthy of investigation. I don’t claim that any of them are correct.

I do claim, however, that we won’t get very far understanding the issue by shifting definitions and muddying the waters with misleading but attention grabbing statistics.

When foundations and behavioral economists write soap operas

Brendan Greeley has the scoop:

Before she won an Academy Award in 2014 for her role in 12 Years a Slave, Lupita Nyong’o starred in two seasons of the TV drama Shuga. Set first in Nairobi and then in Lagos, Shuga features young, attractive people who sleep with each other. It’s wildly popular and shown on broadcast channels that reach 500 million people, mostly in Africa.

“I would say that it’s an African version of Gossip Girl, but with sexual-health messages weaved through,” says Georgia Arnold, executive director of MTV’s Staying Alive Foundation, which produces the show with the twin goals of promoting safer sex and removing the taboo around HIV. Shuga isn’t a commercial project; it’s sponsored by donors including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Now in its fourth season, the show recently added a new member to its production team: Eliana La Ferrara, a professor at the University of Bocconi in Italy who specializes in a mix of behavioral and development economics. La Ferrara wasn’t hired for her writing talent. MTV and its donors want to apply a more rigorous approach to make sure Shuga’s message actually creates change where it airs.

The article has numerous other points of interest.

What will European QE look like? And will it work?

Claire Jones at the FT reports:

The European Central Bank is set to unveil a programme of mass bond buying next week to save the eurozone from deflation, but has bowed to German pressure to ensure that its taxpayers are not liable for any losses incurred on other countries’ debt.

This is not a surprise. Alen Mattich had a good Twitter comment:

How could you trust ECB promise to “do whatever it takes” if it doesn’t accept the risk of holding national sov debt on its books?

Guntram B. Wolff has an excellent, detailed analysis, worth reading in full, here is one bit:

So the purely national purchase of national sovereign debt would either leave the private creditors as junior creditors, or the national central bank has to accept negative equity. What would negative equity mean for a central bank? De facto it would mean that the national central bank, that has created euros to buy government debt, would have lost the claim on the government. It would still owe the euros it has created to the rest of the Eurosystem.(4) The Eurosystem could now either ask the national central bank to return that liability, which it is unable to do without a recapitalisation of its government. Or, the Eurosystem could decide to leave the claim standing relative to the national central bank. In that case, the loss made on the sovereign debt would de facto have been transferred to the Eurosystem. In other words, the attempt to leave default risk with the national central bank will have failed.

…Overall, this discussion shows that monetary policy in the monetary union reaches the limits of feasibility if the principle of joint and several liability at the level of the Eurosystem is given up.

An important open issue is whether the ECB could buy Greek bonds, given that they are up for restructuring and (presumably) the Bank cannot voluntarily relieve Greece of any debt (see Wolff’s discussion). There are plenty of rumors that Greece will indeed be excluded from any QE program, unless you imagine they settle things with the Troika rather more quickly than they are likely to. Yet a bond-buying program without Hellenic participation doesn’t seem so far from hurling an “eurozone heraus!” painted brick through their front window in the middle of the night.

Overall, shuffling assets and risk profiles between national monetary authorities and national fiscal authorities would seem to accomplish…nothing. Not buying up the debt of your biggest problem country also seems to accomplish nothing, in fact it is worth than doing nothing.

Here is my 2012 column on how the eurozone needs to agree on who is picking up the check. They still haven’t agreed! In the meantime, Grexit is a very real possibility, through deposit flight, no matter how badly Greek citizens may wish their country to stay in.

So, so far I am not so optimistic about this whole eurozone QE business, even though in principle I very much favor the idea. It is again a case of politics getting in the way of a problem which does indeed have a (partial) economic solution. The only way it (partially) works is if it (implicitly) bundles debt relief with higher rates of price inflation. Have a nice day.

Why the Republicans are finding it hard to reform Obamacare

Ezra Klein has an excellent essay on this topic, reviewing the (very good) Philip Klein book. Here is one bit:

Klein’s book is a service: it’s far and away the clearest, most detailed look at conservative health-policy thinking in the post-Obamacare world. But it can leave a reader with the impression that the important cleavages in conservative health-policy thinking are between the Replacers, the Reformists, and the Restarters.

It’s not. It’s between those in the party who want to prioritize health reform and those who don’t. And it’s worth being clear: those who don’t have a case. Health reform is an incredibly tough, painful project. Everything you do has tradeoffs, some of them awful.

And to sum up, the Democrats really cared about health care reform (for better or worse), but:

…that’s really the problem for conservative health reformers. For all the plans floating around, there’s little evidence Republicans care enough about health reform to pay its cost.

I am less positive on Obamacare than is Ezra, but still the piece is interesting throughout and a good challenge to would-be reformers.

Assorted links

2. Jeffrey Sachs on the war with radical Islam.

3. Dani Rodrik calls for “the innovation state.”

4. A new hypothesis for gender under-representation across academic fields. More here from Science. Admits of alternative interpretations.

5. How far are you willing to push the Pareto principle?

6. Economic history link dump splat (recommended, for some).

Why did the Swiss break the peg of the franc?

Paul Krugman writes:

Two things to bear in mind. First, having in effect thrown away its credibility – in today’s world, the crucial credibility central banks need involves, not willingness to take away the punch bowl, but willingness to keep pushing liquor on an abstemious crowd – it’s hard to see how the SNB can get it back. Second, there will be spillovers: the SNB’s wimp-out will make life harder for monetary policy in other countries, because it will leave markets skeptical about whether other supposed commitments to keep up unconventional policy will similarly prove time-limited.

Brad DeLong and Scott Sumner agree the Swiss move was a bad idea. We’re all in accord on the economics (more or less), but I am more interested in a different question. The Swiss central bank, had it continued the peg, probably would have had a balance sheet larger than Swiss gdp. But does this matter? Should anyone care? Or does that make them “too big a guy on the block”?

I see two views of the world running around in these discussions, but not always articulated as such:

1. Bureaucrats, which includes central bankers, are not so much budget maximizers as hoarders of institutional capital. They hoard institutional capital when they should be spending it down, in the interests of the broader polity. So this is a public choice problem, rather than a matter of macroeconomic ignorance. When it comes to macroeconomics, we need institutional reforms which induce them or maybe even require them to spend down this capital, come what may for their personal levels of political influence.

2. Bureaucrats hoard and indeed extend institutional capital because they know how important it is to maintain the quality of significant institutions, such as central banks. Without such capital , semi-independent central banks would soon cease to exist, to the detriment of us all. Outside academics, however, rarely can see the importance of this factor, because they have less experience running political institutions. When smart central bankers — which yes includes the Swiss — are apparently doing the wrong thing, it is because they are seeing more variables of the problem than we are. They either cannot do “the right thing,” or doing that would be too costly in terms of the country’s longer-term institutional prospects.

By the way, there is also #3, which I do not find credible:

3. The Swiss central bankers suddenly became stupid and forgot their macroeconomics.

I agree there is plenty of #1 out there, maybe for Switzerland too. But I’d like to see more debate of #1 vs. #2, because I don’t think the Swiss central bankers — praised extravagantly by many of us not too long ago — simply would tank their economy for no good reason at all.

Addendum: Here is Dean Baker’s dissent, although I think the stock market does not agree. And Scott Sumner comments, he seems to opt for #3. Here are useful comments from the FT.

Most water problems can be solved by better property rights and higher prices

In his 2011 book Brahma Chellany reports:

…Singapore has pursued demand management through greater water productivity and efficiency. By plugging system leaks and inefficiencies and raising the price of domestic water, with the tariff and tax rising steeply after the first 40 m3 a month, it managed to reduce household water use by about 10 percent since the mid-1990s to about 155 liters per person per day in 2011. That consumption level is nearly four times lower than that of an average American.

That is from Water: Asia’s New Battleground, which is actually one of the most interesting political economy books published in the last few years.

I liked Noah Smith’s piece and I don’t mean to pick on him, but…

His recent coverage offered a simple means of testing my earlier claim that not one in fifty economists understands the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem (HOT). Noah wrote:

No. 9. The Hecksher-Ohlin theorem

This is a theory about trade. It says that countries with more capital — industrialized countries such as the U.S. or Japan — will tend to make things that are more capital-intensive. And countries with more labor — such as India — will tend to make things that are more labor-intensive. That’s why the U.S. makes a lot of semiconductors (which require huge fabrication plants), and India makes a lot of clothes.

Admittedly, some of the problems in this may stem from the reality that Noah is writing for a largely non-academic audience. Nonetheless here are a few points:

1. The HOT proposition is about exports being relatively capital- or labor-intensive, not about production per se. Even for a popular audience, I think that substitution should have been easy enough.

2. In the HOT literature there is a tension between quantity of labor and quality of labor, or human capital. Some researchers wish to consider the United States as a labor-intensive country for this reason, because in value terms, rather than “counting bodies” terms, we have a lot of talent. That also might help explain Silicon Valley exports and also entertainment exports. Indeed it has been known since Leontief that U.S. exports are relatively labor-intensive, not capital-intensive.

3. The HOT claim is about a country’s capital to labor ratio, so that India has “more labor” is not exactly right, rather India has a lot of labor relative to its supply of capital. Again, this simplification may have been imposed on Noah by the medium, but I am not convinced that the notion of a ratio here is beyond those who read economics on Bloomberg.

4. Here is a recent headline: “China just surpassed the U.S. in semiconductor manufacturing, and the trend is likely to continue.” I say China and the U.S. don’t have the same strengths when it comes to factor endowments, yet they are both producing lots of semiconductors (NB: I don’t have data handy on Chinese semiconductor exports). Probably semiconductors are a classic example of economies of scale, knowledge economies, and specialization. In that case the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem ought not to apply and we move closer to the trade work of Paul Krugman and others. HOT also assumes that all countries enjoy the same state of technical knowledge, which seems doubtful when it comes to semiconductors, and thus maybe relative factor endowments are not doing the work in this case. It seems like semiconductors are an example deliberately chosen to stand as far apart from the Heckscher-Ohlin assumptions as possible.

Now Noah knows way more economics than most economists, and thus I continue to believe most economists don’t have such a clear sense of the Hechscker-Ohlin theorem. There are so many tricks to HOT I wouldn’t be surprised if I slipped up somewhere myself in this post.

Further assorted links

1. Work as a program manager for Scott Sumner.

2. Comparison with other oil price drops.

3. Confessions of a former TSA worker (speculative).

4. Securities law professors against Gallagher and Grundfest.

5. Thomas Piketty responds to critics from the Left, other interesting parts too.

Poland yikes fact of the day

Fully 46 percent of Polish home loans are denominated in Swiss francs.

That is from Matt, hat tip goes to Alex T. Does anyone know the figure for Hungary?

Technology doesn’t always make you more stressed out

Here is a very interesting piece by Claire Cain Miller, here is one excerpt:

The Pew and Rutgers researchers measured stress levels in a representative group of people by using a standard stress scale that ranks people’s responses to questions about their lives. Then they measured their frequency of digital technology use. They controlled for demographic factors like marital and education status.

They found no effect on stress levels among technology users over all. And women who frequently use Twitter, email and photo-sharing apps scored 21 percent lower on the stress scale than those who did not.

That could be because sharing life events enhances well-being, social scientists say, and women tend to do it more than men both online and off. Technology seems to provide “a low-demand and easily accessible coping mechanism that is not experienced or taken advantage of by men,” the report said.

Social media, particularly Facebook, increased stress in one way: by making people more aware of trauma in the lives of close friends. This effect was strongest for women. The finding bolsters the notion that stress can be contagious, the Pew and Rutgers researchers said.

But when such users of social media were exposed to stressful events in the lives of people who were not close friends, the users reported lower stress levels. Researchers said that was perhaps attributable to gratitude for their own lives being free of these stressors (the joy of missing out, offsetting the fear of missing out.)

Do read the whole thing.

Oh, the Swiss franc went up 39% today

By the way, it doesn’t seem to be settling at 39% up (18% as of late), but that was the FT headline. The Economist offers some commentary:

Some analysts speculated that political pressure may have caused the Swiss to abandon the policy; in November last year, a referendum campaign to force the SNB to hold 20% of its balance sheet in gold (which would have made it more difficult to maintain the cap) was defeated. But others felt that the SNB may be expecting the European central Bank to announce quantitative easing in the near future; a shift that would weaken the euro and require even more intervention to cap the franc. In a hole, the SNB may have decided to stop digging.

Swiss equities were down over thirteen percent. And this means a revaluation of Swiss-franc denominated mortgages, which are plentiful in Eastern Europe, Russia and Hungary come to mind first. And it raises the question of how much we can trust central bank commitments, looking forward…

Here is summary coverage from Neil Irwin.

A simple theory of some current basketball surprises

Apply a dose of science and big data to a team sport such as basketball. The big gains will come in cooperation. Who should take the next shot?, when is a “corner three” worthwhile?, who should play with the second unit, how good is the pick and roll against this opponent?, and so on. Big data also will bring some gains at the individual level, such as from better training regimens, but those moves were easier to spot in the first place. The issues involving cooperation are those where simple intuitive observation, of the old school style, will miss a lot of potential improvements.

Cooperative gains are more fragile, however, because everyone has to get the strategy right to reap the benefits (think of Michael Kremer’s O-Ring model). So the previous champion, San Antonio, has fallen off dramatically because Leonard is injured and Tony Parker is playing like his age (32). Atlanta suddenly had all the pieces gel, and they now, to the surprise of almost everyone, have the best record in the East. (They have learned the ball movement and shooting style which San Antonio perfected last year during their championship run, but Atlanta has no big stars.) Golden State is a positive surprise too, with the best record in the league. Cleveland has attempted to do “cooperation” (ha) on the terms of its stars, not on the terms of the data, and that experiment has fallen flat.

In Panama I watched an old Lakers game from the 1980s (vs. Portland) and was struck by how tall everyone was, compared to today. There were fewer surprises that year, and I believe those facts are related. The three-point shot has made players shorter and more cooperative and arguably increased the value of the coach and his assistants.

Some of these arguments should apply to areas other than basketball, so perhaps a higher value for data-driven cooperation will mean more surprises in the world in general.

Assorted links

1. Stimulus and jobs, hard to have it both ways.

2. How has economic convergence changed over time?

3. Philosophers on why they went into philosophy.

4. Korean adoptees returning home to Korea.

5. Philip Klein’s Overcoming Obamacare is a very useful and well-written guide to alternatives to ACA, although I am not sure the reader comes away especially heartened or optimistic. Aaron Carroll reviews the book, mostly positively (though he disagrees), Veronique de Rugy has coverage also.