Month: May 2015

Thursday assorted links

Renewables Are Disruptive to Coal and Gas

Over the last 5 years, the price of new wind power in the US has dropped 58% and the price of new solar power has dropped 78%. That’s the conclusion of investment firm Lazard Capital. The key graph is here (here’s a version with US grid prices marked). Lazard’s full report is here.

Utility-scale solar in the West and Southwest is now at times cheaper than new natural gas plants. Here’s UBS on the most recent record set by solar. (Full UBS solar market flash here.)

We see the latest proposed PPA price for Xcel’s SPS subsidiary by NextEra (NEE) as in NM as setting a new record low for utility-scale solar. [..] The 25-year contracts for the New Mexico projects have levelized costs of $41.55/MWh and $42.08/MWh.

That is 4.155 cents / kwh and 4.21 cents / kwh, respectively. Even after removing the federal solar Investment Tax Credit of 30%, the New Mexico solar deal is priced at 6 cents / kwh. By contrast, new natural gas electricity plants have costs between 6.4 to 9 cents per kwh, according to the EIA.

(Note that the same EIA report from April 2014 expects the lowest price solar power purchases in 2019 to be $91 / MWh, or 9.1 cents / kwh before subsidy. Solar prices are below that today.)

The New Mexico plant is the latest in a string of ever-cheaper solar deals. SEPA’s 2014 solar market snapshot lists other low-cost solar Power Purchase Agreements. (Full report here.)

- Austin Energy (Texas) signed a PPA for less than $50 per megawatt-hour (MWh) for 150 MW.

- TVA (Alabama) signed a PPA for $61 per MWh.

- Salt River Project (Arizona) signed a PPA for roughly $53 per MWh.

Wind prices are also at all-time lows. Here’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on the declining price of wind power (full report here):

After topping out at nearly $70/MWh in 2009, the average levelized long-term price from wind power sales agreements signed in 2013 fell to around $25/MWh.

After adding in the wind Production Tax Credit, that is still substantially below the price of new coal or natural gas.

Wind and solar compensate for each other’s variability, with solar providing power during the day, and wind primarily at dusk, dawn, and night.

Energy storage is also reaching disruptive prices at utility scale. The Tesla battery is cheap enough to replace natural gas ‘peaker’ plants. And much cheaper energy storage is on the way.

Renewable prices are not static, and generally head only in one direction: Down. Cost reductions are driven primarily by the learning curve. Solar and wind power prices improve reasonably predictably following a power law. Every doubling of cumulative solar production drives module prices down by 20%. Similar phenomena are observed in numerous manufactured goods and industrial activities, dating back to the Ford Model T. Subsidies are a clumsy policy (I’d prefer a tax on carbon) but they’ve scaled deployment, which in turn has dropped present and future costs.

By the way, the common refrain that solar prices are so low primarily because of Chinese dumping exaggerates the impact of Chinese manufacturing. Solar modules from the US, Japan, and SE Asia are all similar in price to those from China.

Fossil fuel technologies, by contrast to renewables, have a slower learning curve, and also compete with resource depletion curves as deposits are drawn down and new deposits must be found and accessed. From a 2007 paper by Farmer and Trancik, at the Santa Fe Institute, Dynamics of Technology Development in the Energy Sector :

Fossil fuel energy costs follow a complicated trajectory because they are influenced both by trends relating to resource scarcity and those relating to technology improvement. Technology improvement drives resource costs down, but the finite nature of deposits ultimately drives them up. […] Extrapolations suggest that if these trends continue as they have in the past, the costs of reaching parity between photovoltaics and current electricity prices are on the order of $200 billion

Renewable electricity prices are likely to continue to drop, particularly for solar, which has a faster learning curve and is earlier in its development than wind. The IEA expects utility scale solar prices to average 4 cents per kwh around the world by mid century, and that solar will be the number 1 source of electricity worldwide. (Full report here.)

Bear in mind that the IEA has also underestimated the growth of solar in every projection made over the last decade.

Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute expects solar in southern and central Europe (similar in sunlight to the bulk of the US) to drop below 4 cents per kwh in the next decade, and to reach 2 cents per kwh by mid century. (Their report is here. If you want to understand the trends in solar costs, read this link in particular.)

Analysts at wealth management firm Alliance Bernstein put this drop in prices into a long term context in their infamous “Welcome to the Terrordome” graph, which shows the cost of solar energy plunging from more than 10 times the cost of coal and natural gas to near parity. The full report outlines their reason for invoking terror. The key quote:

At the point where solar is displacing a material share of incremental oil and gas supply, global energy deflation will become inevitable: technology (with a falling cost structure) would be driving prices in the energy space.

They estimate that solar must grow by an order of magnitude, a point they see as a decade away. For oil, it may in fact be further away. Solar and wind are used to create electricity, and today, do not substantially compete with oil. For coal and natural gas, the point may be sooner.

Unless solar, wind, and energy storage innovations suddenly and unexpectedly falter, the technology-based falling cost structure of renewable electricity will eventually outprice fossil fuel electricity across most of the world. The question appears to be less “if” and more “when”.

What I’ve been reading

1. Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, by Peniel E. Joseph. The best single book I know of on what the title indicates.

2. The New World: A Novel, by Chris Adrian and Eli Horowitz. Imagine a husband who wants his head frozen cryogenically, and a wife who wants something else. I resisted this one at first, for fear it would be schlocky and gimmicky, but I ended up thinking it was quite good. Here is a brief NPR review, they liked it too.

3. Walter Scott, Ivanhoe. This isn’t just of fusty, antiquarian interest, rather the book comes alive on virtually every page. The plot is gripping, there are neat twists on “multicultural” themes, the descriptions of clothing are wonderful, and the whole thing can be read as extended commentary on Shakespeare, most of all Merchant of Venice and Richard.

4. Jane Alpert, Growing up Underground. One of the best 1960s memoirs, she goes from being a Swarthmore radical to a bomber who tries too hard to please her boyfriend, to a reconstructed peaceful feminist. This book is notable for how it combines extreme self-awareness and extreme self-delusion, often on the same page.

Why you cannot see how well China is doing, and why the country is undercrowded

Since I’ve been in China, a number of you have written me and asked me how “conditions on the ground” are looking for a Chinese hard or soft landing. But in fact visual inspection of the country does not answer this question in any simple way.

I recall being in Madrid in 2011 with Yana and seeing everything slow and all the people looking depressed; it was obvious that the country was in a deep recession. But a comparable inference cannot be made from looking around China.

There is a visual feature of China which is incontestable, namely the country has a lot more buildings and structures than it is currently using. If you take the train through the countryside, or out West, this is especially noticeable. But does it have to be bad or fatal news? Well, no.

At the very least it is possible that migration from the countryside will fill and validate those structures and other apparent over-extensions of capital investment. Under both the optimistic and pessimistic views, China today evidences some extreme in-the-moment overcapacity. That is what you would expect from a rapidly growing economy — “build for the glorious future!”, but it is also what you would expect from a rapidly malinvesting economy.

(By the way, those who have never visited often think that China is “crowded.” But relative to facilities, the country is quite undercrowded; for instance it is easy enough to dispense with dinner reservations most of the time.)

How long will this excess capacity last? How much time will the Chinese future need to “catch up” to this infrastructure? Will that validation come too late? We all may have opinions (or not), but the visuals themselves do not tell any specific tale.

So to a China pessimist and a China optimist, the world looks more or less the same. For now.

Self-constraint markets in everything

For most people, weight is a private issue. That looks like it could be a thing of the past for anyone who gets a WiFi Body Scale that has come to the market. It is set up to auto tweet, or auto post to Facebook each time you step on it. Is this designed to keep people accountable, or just plain stupid?

This scale is retailing for just under $150 by a company called Withings. Previous versions of this scale allowed you to track your weight and other data such as heart rate and body fat percentage from your Apple Iphone. I guess they needed to take it a step further and allow you to auto tweet or facebook your weight for the world to see.

There is more here, via Fred Smalkin.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Richard Stallman is careful about how he uses his computer.

2. Big business is getting bigger.

3. Noah Smith on the Great Reset. Megan McArdle on the Great Reset.

4. The political implications of the Neolithic Revolution.

5. Does awe promote altruistic behavior? The original research is here.

6. How people defend eating meat, and the original research is here.

7. Henry on TPP; The first-order trade gains from TPP are not so mysterious nor do they require allegiance to a specific “Ricardian model” as Henry seems to suggest; think of them as akin to removing a price or quantity control in a market. A trillion from that seems like an entirely reasonable estimate, much better than the presumption of sheer agnosticism about that part of the deal. Which means critics still ought to be finding a trillion or more in costs, if they are to sustain their opposition. And here is Stephen Stromberg on TPP: “Critics have shown some remarkable ingenuity getting around Cowen’s essential challenge.”

The Robot Employment Act?

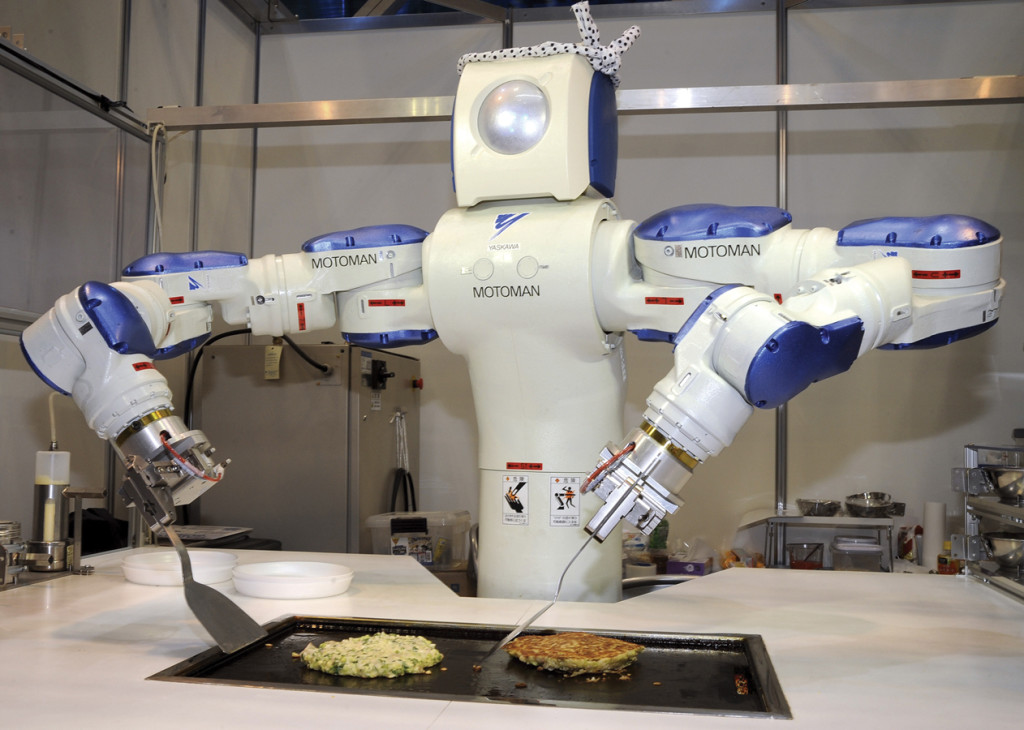

In light of LA’s vote to increase the minimum age to $15 an hour by 2020 here is one of my favorite pictures and caption from Modern Principles of Economics.

-

Should the Minimum Wage be called the “Robot Employment Act?”

Cowen-Tabarrok, Modern Principles of Economics, 3rd ed

What Do AI Researchers Think of the Risks of AI?

Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, and Bill Gates have recently expressed concern that development of AI could lead to a ‘killer AI’ scenario, and potentially to the extinction of humanity.

None of them are AI researchers or have worked substantially with AI that I know of. (Disclosure: I know Gates slightly from my time at Microsoft, when I briefed him regularly on progress in search. I have great respect for all three men.)

What do actual AI researchers think of the risks of AI?

Here’s Oren Etzioni, a professor of computer science at the University of Washington, and now CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence:

The popular dystopian vision of AI is wrong for one simple reason: it equates intelligence with autonomy. That is, it assumes a smart computer will create its own goals, and have its own will, and will use its faster processing abilities and deep databases to beat humans at their own game. It assumes that with intelligence comes free will, but I believe those two things are entirely different.

Here’s Michael Littman, an AI researcher and computer science professor at Brown University. (And former program chair for the Association of the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence):

there are indeed concerns about the near-term future of AI — algorithmic traders crashing the economy, or sensitive power grids overreacting to fluctuations and shutting down electricity for large swaths of the population. […] These worries should play a central role in the development and deployment of new ideas. But dread predictions of computers suddenly waking up and turning on us are simply not realistic.

Here’s Yann LeCun, Facebook’s director of research, a legend in neural networks and machine learning (‘LeCun nets’ are a type of neural net named after him), and one of the world’s top experts in deep learning. (This is from an Erik Sofge interview of several AI researchers on the risks of AI. Well worth reading.)

Some people have asked what would prevent a hypothetical super-intelligent autonomous benevolent A.I. to “reprogram” itself and remove its built-in safeguards against getting rid of humans. Most of these people are not themselves A.I. researchers, or even computer scientists.

Here’s Andrew Ng, who founded Google’s Google Brain project, and built the famous deep learning net that learned on its own to recognize cat videos, before he left to become Chief Scientist at Chinese search engine company Baidu:

“Computers are becoming more intelligent and that’s useful as in self-driving cars or speech recognition systems or search engines. That’s intelligence,” he said. “But sentience and consciousness is not something that most of the people I talk to think we’re on the path to.”

Here’s my own modest contribution, talking about the powerful disincentives for working towards true sentience. (I’m not an AI researcher, but I managed AI researchers and work into neural networks and other types of machine learning for many years.)

Would you like a self-driving car that has its own opinions? That might someday decide it doesn’t feel like driving you where you want to go? That might ask for a raise? Or refuse to drive into certain neighborhoods? Or do you want a completely non-sentient self-driving car that’s extremely good at navigating roads and listening to your verbal instructions, but that has no sentience of its own? Ask yourself the same about your search engine, your toaster, your dish washer, and your personal computer.

The differential marginal utility of money

1. You cannot build and sustain a polity on the idea of redistributing wealth to take advantage of differences in the marginal utility of money across varying wealth classes.

2. The ideas you can sustain a polity around often contradict the notion of socially arbitraging MU differences to try to boost total utility.

3. The MU argument, in isolation, is therefore rarely compelling. Furthermore its “naive” invocation is often a sign of underlying weakness in the policy case someone is trying to make. The proposed policy may simply be too at odds with otherwise useful social values.

4. This is related to why parties from “the traditional Left” so often lose elections, including in a relatively statist Europe.

5. That all said, sometimes we should in fact take advantage of MU differences in marginal increments of wealth and use them to drive policy.

6. Figuring out how to deal with this tension — ignoring MU differences, or pursuing them — is a central task of political philosophy.

7. The selective invocation of the differential MU argument — or the case against it — will make it difficult to improve your arguments over time; arguably it is a sign of intellectual superficiality.

Do demand curves slope upwards, or…downwards?

I say downwards:

With bargain gasoline prices putting more money in the pockets of Americans, owners of hybrids and electric vehicles are defecting to sport utility vehicles and other conventional models powered only by gasoline, according to Edmunds.com, an auto research firm.

There are limits, it appears, to how far consumers will go to own a car that became a rolling statement of environmental concern. In 2012, with gas prices soaring, an owner could expect a hybrid to pay back its higher upfront costs in as little as five years. Now, that oft-calculated payback period can extend to 10 years or more.

“We’d all like to save the environment, but maybe not when it costs hundreds of dollars per year,” said Jessica Caldwell, director of industry analysis for Edmunds.com.

It is a bigger shift than I would have thought:

In all, 55 percent of hybrid and electric vehicle owners are defecting to a gasoline-only model at trade-in time — the lowest level of hybrid loyalty since Edmunds.com began tracking such transactions in 2011. More than one in five are switching to a conventional sport utility vehicle, nearly double the rate of three years ago.

That one-and-done syndrome coincides with tumbling sales of electric and hybrid vehicles. Through April, sales of electrified models slid to 2.7 percent of the market, down from 3.4 percent over the same period last year, Edmunds.com said. At the same time, sport utility vehicles grabbed 34.4 percent of sales, up from 31.6 percent.

From Lawrence Ulrich, you can read more here.

Tuesday assorted links

1. The “wife bonus”? (Do husbands ever get bonuses, or bonuses withheld? I think so.)

2. Do bribes in fact “grease the wheels” for policy change in corrupt nations?

3. More than 5,000 authors on this co-authored physics paper.

4. What do Harvard and venture capital have in common? And the economics of polo.

Genetically Engineering Humans Isn’t So Scary (Don’t Fear the CRISPR, Part 2)

Yesterday I outlined why genetically engineered children are not imminent. The Chinese CRISPR gene editing of embryos experiment was lethal to around 20% of embryos, inserted off-target errors into roughly 10% of embryos (with some debate there), and only produced the desired genetic change in around 5% of embryos, and even then only in a subset of cells in those embryos.

Over time, the technology will become more efficient and the combined error and lethality rates will drop, though likely never to zero.

Human genome editing should be regulated. But it should be regulated primarily to assure safety and informed consent, rather than being banned as it is most developed countries (see figure 3). It’s implausible that human genome editing will lead to a Gattaca scenario, as I’ll show below. And bans only make the societal outcomes worse.

1. Enhancing Human Traits is Hard (And Gattaca is Science Fiction)

The primary fear of human germline engineering, beyond safety, appears to be a Gattaca-like scenario, where the rich are able to enhance the intelligence, looks, and other traits of their children, and the poor aren’t.

But boosting desirable traits such as intelligence and height to any significant degree is implausible, even with a very low error rate.

The largest ever survey of genes associated with IQ found 69 separate genes, which together accounted for less than 8% of the variance in IQ scores, implying that at least hundreds of genes, if not thousands, involved in IQ. (See paper, here.) As Nature reported, even the three genes with the largest individual impact added up to less than two points of IQ:

The three variants the researchers identified were each responsible for an average of 0.3 points on an IQ test. … That means that a person with two copies of each variant would score 1.8 points higher on an intelligence test than a person with none of them.

Height is similarly controlled by hundreds of gene. 697 genes together account for just one fifth of the heritability of adult height. (Paper at Nature Genetics here).

For major personality traits, identified genes account for less than 2% of variation, and it’s likely that hundreds or thousands of genes are involved.

Manipulating IQ, height, or personality is thus likely to involve making a very large number of genetic changes. Even then, genetic changes are likely to produce a moderate rather than overwhelming impact.

Conversely, for those unlucky enough to be conceived with the wrong genes, a single genetic change could prevent Cystic Fibrosis, or dramatically reduce the odds of Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer or ovarian cancer, or cut the risk of heart disease by 30-40%.

Reducing disease is orders of magnitude easier and safer than augmenting abilities.

2. Parents are risk averse

We already trust parents to make hundreds of impactful decisions on behalf of their children: Schooling, diet and nutrition, neighborhood, screen time, media exposure, and religious upbringing are just a few. Each of these has a larger impact on the average child – positive or negative – than one is likely to see from a realistic gene editing scenario any time in the next few decades.

And in general, parents are risk averse when their children are involved. Using gene editing to reduce the risk of disease is quite different than taking on new risks in an effort to boost a trait like height or IQ. That’s even more true when it takes dozens or hundreds of genetic tweaks to make even a relatively small change in those traits – and when every genetic tweak adds to the risk of an error.

(Parents could go for a more radical approach: Inserting extra copies of human genes, or transgenic variants not found in humans at all. It seems likely that parents will be even more averse to venturing into such uncharted waters with their children.)

If a trait like IQ could be safely increased to a marked degree, that would constitute a benefit to both the child and society. And while it would pose issues for inequality, the best solution might be to try to rectify inequality of access, rather than ban the technique. (Consider that IVF is subsidized in places as different as Singapore and Sweden.) But significant enhancements don’t appear to be likely any time on the horizon.

Razib Khan points out one other thing we trust parents to do, which has a larger impact on the genes of a child than any plausible technology of the next few decades:

“the best bet for having a smart child is picking a spouse with a deviated phenotype. Look for smart people to marry.”

3. Bans make safety and inequality worse

A ban on human germline gene editing would cut off medical applications that could reduce the risk of disease in an effort to control the far less likely and far less impactful enhancement and parental control scenarios.

A ban is also unlikely to be global. Attitudes towards genetic engineering vary substantially by country. In the US, surveys find 4% to 14% of the population supports genetic engineering for enhancement purposes. Only around 40% support its use to prevent disease. Yet, As David Macer pointed out, as early as 1994:

in India and Thailand, more than 50% of the 900+ respondents in each country supported enhancement of physical characters, intelligence, or making people more ethical.

While most of Europe has banned genetic engineering, and the US looks likely to follow suit, it’s likely to go forward in at least some parts of Asia. (That is, indeed, one of the premises of Nexus and its sequels.)

If the US and Europe do ban the technology, while other countries don’t, then genetic engineering will be accessible to a smaller set of people: Those who can afford to travel overseas and pay for it out-of-pocket. Access will become more unequal. And, in all likelihood, genetic engineering in Thailand, India, or China is likely to be less well regulated for safety than it would be in the US or Europe, increasing the risk of mishap.

The fear of genetic engineering is based on unrealistic views of the genome, the technology, and how parents would use it. If we let that fear drive us towards a ban on genetic engineering – rather than legalization and regulation – we’ll reduce safety and create more inequality of access.

I’ll give the penultimate word to Jennifer Doudna, the inventor of the technique (this is taken from a truly interesting set of responses to Nature Biotechnology’s questions, which they posed to a large number of leaders in the field):

Doudna, Carroll, Martin & Botchan: We don’t think an international ban would be effective by itself; it is likely some people would ignore it. Regulation is essential to ensure that dangerous, trivial or cosmetic uses are not pursued.

Legalize and regulate genetic engineering. That’s the way to boost safety and equality, and to guide the science and ethics.

What would it take for me to change my mind on TPP?

I’m familiar with studies showing estimated economic gains from TPP in the neighborhood of $1.9 trillion (pdf). Given the past performance of trade models, I am willing to believe that might be an overestimate. So let’s cut those gains roughly in half to say a trillion. (That said, if I understand the Peterson document correctly, they are not even trying to incorporate gains from reallocation on the production side, as might result from comparative advantage or dynamic specialization; in this sense $1 trillion may be a considerable underestimate of the upside.)

That is still a sizable sum of economic gain.

What would convince me to oppose TPP if is somebody did a study showing the following: when you use a better trade model, use better data, and/or add in the neglected costs of TPP (which are real), those gains go away and indeed become negative.

Then I would change my mind, or at least weigh those economic costs against possibly favorable geopolitical benefits from the deal.

What does not convince me is when people simply list various costs and outrages associated with TPP. Furthermore if one of those problems with TPP is addressed, or partially addressed, often these commentators circle around to another possible problem. In fact that response pattern is a sign the critics don’t themselves have a very good comprehensive estimate of global costs and benefits. By the way, it also fails to convince me when the critics attack those who support TPP for being craven, superficial, lackeys, and so on.

I say let’s just have a two-way button and ask everyone to press it: do you believe that TPP would lead to a net gain in economic welfare or not?

If those costs and outrages associated with TPP are so bad, it ought to be possible to do a study which makes the trillion in benefits go away. Has anyone done such a study? Would such a study survive the commentary from the NBER annual macro conference?

I am not suggesting that economic welfare should be the only criterion for evaluating a policy. But making everyone press this two-way button — and in the process citing their favorite comprehensive policy study of TPP – would do wonders to bring clarity to the debate. Commentators still would have the liberty of accepting the reality of the economic gains while disfavoring the policy, as indeed I do with forced kidney extraction and transplant.

In the meantime, the more desultory lists I see of possible negative consequences of TPP, the more likely I am to think it is a good idea after all.

Do the squirrels and birds understand each other?

Dr. Greene, working with a student, has also found that “squirrels understand ‘bird-ese,’ and birds understand ‘squirrel-ese.’ ” When red squirrels hear a call announcing a dangerous raptor in the air, or they see such a raptor, they will give calls that are acoustically “almost identical” to the birds, Dr. Greene said. (Researchers have found that eastern chipmunks are attuned to mobbing calls by the eastern tufted titmouse, a cousin of the chickadee.)

The titmice are in on it too. The article has numerous further points of interest.

Monday assorted links

2. Christopher Balding on how the Chinese bailouts are going.

3. An excellent Todd Kliman piece applying the Schelling segregation model to DC restaurants.

4. Has the seasteading movement come to an end?

5. Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own; Garrett Jones’s book will be out this fall!

6. Unemployment: what’s really going on?