Month: October 2015

Mind both your p’s and your q’s

Here is a new and very clear Diane Coyle piece about whether gdp and CPI statistics are failing us. Perhaps we are overestimating the rate of inflation and thus underestimating real wage growth, as many of the economic optimists suggest. Yet I do not find that “the q’s” support this case made for “the p’s.” For instance the employment-population ratio remains quite low, though with some small recent upticks. If real wages were up so much, you might expect a larger adjustment from the q’s, namely the quantities of labor supplied.

Similarly, there is net Mexican migration out of the United States. You might not expect that if recent innovations were creating significant unmeasured real wage gains.

Investment performance, while hard to measure, also seems sluggish.

Again, a closer look at the q’s makes it harder to be very optimistic about the p’s.

*The Invention of Science*

That is the new, magisterial and explicitly Whiggish book by David Wootton, with the subtitle A New History of Scientific Revolution.

I wish there were a single word for the designator “deep, clear, and quite well written, though it will not snag the attention of the casual reader of popular science books because it requires knowledge of the extant literature on the history of science.” Here is one excerpt, less specific than most of the book:

My argument so far is that the seventeenth-century mathematization of the world was long in preparation. Perspective painting, ballistics and fortification, cartography and navigation prepared the ground for Galileo, Descartes and Newton. The new metaphysics of the seventeenth century, which treated space as abstract and infinite, and location and movement as relative, was grounded in the new mathematical sciences of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and if we want to trace the beginnings of the Scientific Revolution we will need to go back to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, to double-entry bookkeeping, to Alberti and Regiomontanus. The Scientific Revolution was, first and foremost, a revolt by the mathematicians against the authority of the philosophers.

769 pp., recommended — for some of you.

I had to order my copy from UK, in the US it comes out in December and can be pre-ordered.

The self-tracking pill

Some morning in the future, you take a pill — maybe something for depression or cholesterol. You take it every morning.

Buried inside the pill is a sand-sized grain, one millimeter square and a third of a millimeter thick, made from copper, magnesium, and silicon. When the pill reaches your stomach, your stomach acids form a circuit with the copper and magnesium, powering up a microchip. Soon, the entire contraption will dissolve, but in the five minutes before that happens, the chip taps out a steady rhythm of electrical pulses, barely audible over the body’s background hum.

The signal travels as far as a patch stuck to your skin near the navel, which verifies the signal, then transmits it wirelessly to your smartphone, which passes it along to your doctor. There’s now a verifiable record that the pill reached your stomach.

This is the vision of Proteus, a new drug-device accepted for review by the Food and Drug Administration last month. The company says it’s the first in a new generation of smart drugs, a new source of data for patients and doctors alike. But bioethicists worry that the same data could be used to control patients, infringing on the intensely personal right to refuse medication and giving insurers new power over patients’ lives. As the device moves closer to market, it raises a serious question: Is tracking medicine worth the risk?

That is from Russell Brandom.

Thursday assorted links

1.The internet hermit. And is your house the most disruptive technology of the last century?

2. The economics of Playboy droppings its nudes.

3. Model this: “The Philippines’ leading fast-food giant Jollibee Foods announced on Tuesday it had acquired 40 percent of an upmarket US hamburger chain [Smashburger] for $99 million.”

4. New algorithm can erase tourists from your photos.

There is a new Clay Shirky book

Americas fact of the day

…the flow of Europeans to the New World before 1800 did not stand out, at least numerically. Somewhere between 1 million and 2 million Europeans came to the New World between 1500 and 1800; by contrast, over 8 million Africans came via the slave trade. (The predominantly European population of North America resulted from very high birth rates…while wretched conditions and an absence of females kept the African population down.)

That is from Kenneth Pomeranz and Steven Topik, The World That Trade Created, second edition, p.56. And here is Alex’s earlier post on textbooks and slavery.

Leo Strauss’s greatness, according to Dan Klein

1. A sense of virtue/justice/right that is large and challenging.

2. An appreciation of wisdom as something different than progressive research programs/specialized academic fields and disciplines.

3. An understanding of the sociology of judgment, in particular the role of great humans.

4. An epic narrative, from Thucydides to today.

5. Rediscovery, analysis, elaboration, and instruction of esotericism.

6. Close readings and interpretations of great works.

7. Inspiring, cultivating serious students and followers.

I should add that Dan also is developing a counterpart list, of weaknesses in Strauss’s outlook and approach.

Wednesday assorted links

1.Another good reason for not trusting Mundell-Fleming intuitions, this one from Olivier Blanchard and Co.

2. Migration can counteract global warming costs in middle income but not poor countries.

3. Izabella Kaminska transcribes the Star Trek conversation.

5. More on the relative impotence of more progressive taxes.

A conversation with Angus Deaton about RCTs

The interrogator is Timothy N. Ogden, here is one bit from Deaton:

Something I read the other day that I didn’t know, David Greenberg and Mark Shroder, who have a book, The Digest of Social Experiments, claim that 75 percent of the experiments they looked at in 1999, of which there were hundreds, is an experiment done by rich people on poor people. Since then, there have been many more experiments, relatively, launched in the developing world, so that percentage can only have gotten worse. I find that very troubling.

If the implicit theory of policy change underlying RCTs is paternalism, which is what I fear, I’m very much against it.

The conversation is interesting throughout. Tim indicates:

This is a chapter from the forthcoming book Experimental Conversations, to be published by MIT Press in 2016. The book collects interviews with academic and policy leaders on the use of randomized evaluations and field experiments in development economics. To be notified when the book is released, please sign up here.

The book will contain an interview with me as well.

Economics and the Modern Economic Historian

That is a new NBER paper by Ran Abramitzky, the abstract is here:

I reflect on the role of modern economic history in economics. I document a substantial increase in the percentage of papers devoted to economic history in the top-5 economic journals over the last few decades. I discuss how the study of the past has contributed to economics by providing ground to test economic theory, improve economic policy, understand economic mechanisms, and answer big economic questions. Recent graduates in economic history appear to have roughly similar prospects to those of other economists in the economics job market. I speculate how the increase in availability of high quality micro level historical data, the decline in costs of digitizing data, and the use of computationally intensive methods to convert large-scale qualitative information into quantitative data might transform economic history in the future.

I have for a while been pleased that GMU has one of the largest collections of economic historians (I would say four,) of any department around, UC Davis being another major presence in that area.

What is stupid?

Should there not be more research on this apparently simple yet elusive question? Here is a new paper by Acezel, Palfi, and Kekecs:

This paper argues that studying why and when people call certain actions stupid should be the interest of psychological investigations not just because it is a frequent everyday behavior, but also because it is a robust behavioral reflection of the rationalistic expectations to which people adjust their own behavior and expect others to. The relationship of intelligence and intelligent behavior has been the topic of recent debates, yet understanding why we call certain actions stupid irrespective of their cognitive abilities requires the understanding of what people mean when they call an action stupid. To study these questions empirically, we analyzed real-life examples where people called an action stupid. A collection of such stories was categorized by raters along a list of psychological concepts to explore what the causes are that people attribute to the stupid actions observed. We found that people use the label stupid for three separate types of situation: (1) violations of maintaining a balance between confidence and abilities; (2) failures of attention; and (3) lack of control. The level of observed stupidity was always amplified by higher responsibility being attributed to the actor and by the severity of the consequences of the action. These results bring us closer to understanding people’s conception of unintelligent behavior while emphasizing the broader psychological perspectives of studying the attribute of stupid in everyday life.

What do you think people, a smart paper or a stupid paper?

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Deaton on Deaton

It was during my time at Bristol that John Muellbauer and I worked together on our book. The computer facilities at Bristol were terrible — the computer was a mile away, on top of a hill, so that boxes of punched cards had to be lugged up and down. I was told to get a research assistant, which was sensible advice, but I have never really figured out how to use research assistance: for me, the process of data gathering — at first with paper and pencil from books and abstracts — programming, and calculation has always been part of the creative process, and without doing it all, I am unlikely to have the flash of insight that tells me that something doesn’t fit, that not only this model doesn’t work, but that all such models cannot work. Of course, this process has become much easier over time. Not only are data and computing power constantly and easily at one’s fingertips, but it is easy to explore data graphically. The delights and possibilities can only be fully appreciated by someone who spent his or her youth with graph paper, pencils, and erasers.

Given how far it was up the computer hill, I substituted theory for data for a while, and wrote papers on optimal taxation, the structure of preferences, and on quantity and price index numbers, but I never entirely gave up on applied work.

The entire biographical essay is of interest (pdf).

Tuesday assorted links

1. The world’s first airport for drones is being built in…Rwanda.

2. Clive Crook reviews Dani Rodrik on economic method.

3. Robber uses Uber for getaway car. Gets caught. And how many students cheat?

4. The Fairfax police understand search theory, sort of.

5. Did the number of people enrolled in the health care exchanges drop by fifteen percent?

The Case for Getting Rid of Borders—Completely

In The Atlantic I present the case for open borders. Here is one bit:

No standard moral framework, be it utilitarian, libertarian, egalitarian, Rawlsian, Christian, or any other well-developed perspective, regards people from foreign lands as less entitled to exercise their rights—or as inherently possessing less moral worth—than people lucky to have been born in the right place at the right time. Nationalism, of course, discounts the rights, interests, and moral value of “the Other,” but this disposition is inconsistent with our fundamental moral teachings and beliefs.

Freedom of movement is a basic human right. Thus the Universal Declaration of Human Rights belies its name when it proclaims this right only “within the borders of each state.” Human rights do not stop at the border.Today, we treat as pariahs those governments that refuse to let their people exit. I look forward to the day when we treat as pariahs those governments that refuse to let people enter.

Read the whole thing.

Addenda: I was asked to write this piece for a forthcoming volume called How to Save Humanity that will feature essays by Steven Pinker, Martin Rees, Nick Bostom and others.

Open Borders seems to be having a moment. Time also featured a piece on migration by Bryan Caplan.

The comment section at The Atlantic reminded me of how good the comment section at MR can be. Amusingly, I was called both a zionist Jew and an anti-semite out to destroy Israel. On the other hand, my article has 31,000 likes and counting so I can’t complain.

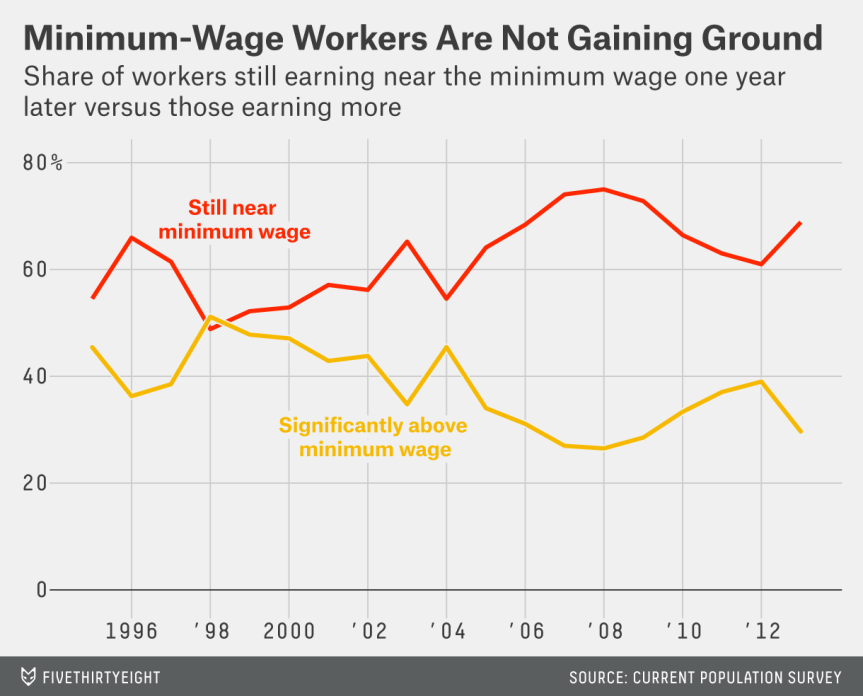

Is it getting harder to move beyond minimum wage jobs?

Ben Casselman has a good piece on this question, here is one excerpt:

During the strong labor market of the mid-1990s, only 1 in 5 minimum-wage workers was still earning minimum wage a year later. Today, that number is nearly 1 in 3, according to my analysis of government survey data. There has been a similar rise in the number of people staying in minimum-wage jobs for three years or longer…

Even those who do get a raise often don’t get much of one: Two-thirds of minimum-wage workers in 2013 were still earning within 10 percent of the minimum wage a year later, up from about half in the 1990s. And two-fifths of Americans earning the minimum wage in 2008 were still in near-minimum-wage jobs five years later, despite the economy steadily improving during much of that time.

The piece is of interest throughout.