Month: June 2016

Intuitions about commodification are culturally relativistic

A non-relative male paying for a meal was once so anomalous that it was considered — and not always incorrectly — prostitution, says Moira Weigel, a Yale University PhD student and the author of the just-published “Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating,” with police officers staking out bars and restaurants and even arresting daters.

That is from Emma Court. See also Jason Brennan.

Thursday assorted links

1. Joshua Gans on adult coloring books.

2. Michelin will start rating D.C. restaurants. They will have to grade on a curve.

3. Are publishers making a mistake by pursuing scale?

4. Which country has the most critical tourists in on-line forums?, the culture that is South Korea. Click the link to see the runners-up.

5. Congratulations to Chris Blattman, who is getting tenure at the University of Chicago.

6. For which embargoed government statistics are there information leaks into financial markets? FOMC no.

7. How would “Medicare for more” interact with the ACA? (NYT, very good piece)

Open and Closed India

In an interview the LSE’s distinguished economic historian Tirthankar Roy was asked how his work on colonial India informs our understanding of contemporary India.

What was similar between the colonial times and the post-reform years? The answer is openness. The parallel tells us that openness to trade and investment is good for capitalism, whether we consider the colonial times or the postcolonial. The open economy did not deliver capitalistic growth in the same fashion in both eras. But there were similarities. In both the periods, not only commodities but also capital and labour were mobile, which encouraged freer flow of knowledge, skills, and technology, and created incentives for domestic producers to become better at what they were doing.

…It is necessary to stress the lesson that open markets and cosmopolitanism were good for the Indian economy, because the political rhetoric in India remains trapped in nationalism, which tends to blame global trade and global capital for poverty and underdevelopment. That sentiment started as a criticism of the British Raj, nurtured by the left, and the negativity persists. The pessimistic view of openness is based on a misreading of economic history. There were many things seriously wrong with the British Raj, but market-integration was not one of these. Influenced by a wrong reading of history, India’s politics remains unnecessarily suspicious of globalisation and cosmopolitanism.

For evidence of rhetoric trapped in nationalism look no further than the Indian government’s refusal to allow Apple to sell used iPhones in India.

Hat tip: Pseudoerasmus on twitter.

Is Indian fertility collapsing?

From Sanjeev Sanyal:

The TFR for rural areas stands at 2.5, but that for urban India is down at 1.8 — marginally below the readings for Britain and the US. An important implication of this is that India’s overall TFR will almost certainly fall below replacement as it rapidly urbanises over the next 20 years.

There continue to be wide variations in the fertility rates across the country. Readings for the southern states have been low for some time, but are now dropping sharply in many northern states.

Tamil Nadu has a TFR of 1.7 but so do Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar continue to have the country’s highest TFR at 3.1 and 3.5 respectively, but these are also falling steadily.

Demise of the Bhadralok Interestingly, West Bengal has the lowest fertility in the country with a TFR reading of 1.6. The level for rural Bengal is 1.8 but is a shockingly low 1.2 for the cities. This is one of the lowest levels in the world and is at par with Singapore and South Korea.

Do read the whole thing. The net Indian TFR is about 2.3, which given gender imbalance and infant and child mortality is already about replacement rate.

How will talking bots affect us?

I have a short New Yorker piece on that question, here is one bit from it:

If Siri is sometimes sarcastic, could heavy users of the Siri of the future become a little more sarcastic, too?

For companies, there are risks associated with such widespread personification. For a time, consumers may be lulled by conversational products into increased intimacy and loyalty. But, later, they may feel especially betrayed by products they’ve come to think of as friends. Like politicians, who build up trust by acting like members of the family only to incur wrath when they are revealed to be careerist and self-interested, companies may find themselves on an emotional roller coaster. They’ll also have to deal with complicated subjects like politics. Recently, Tay, a chat bot from Microsoft, had to be disabled because it began issuing tweets with Nazi-like rhetoric. According to Elizabeth Dwoskin, in the Post, Cortana, another talking Microsoft bot, was carefully programmed not to express favoritism for either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump. A product’s apparent intelligence makes it likable, but also offers more of an opportunity to offend.

Here is another:

And there are ways in which just knowing that bots exist will change us. If the bots are good enough, we won’t be able to distinguish them from actual people over e-mail or text; when you get an e-mail, you won’t necessarily be certain it’s from a human being. When your best friend writes that she’s also “looking forward to seeing you at the baseball game tonight,” you’ll smile—then wonder if she’s busy and has asked her e-mail bot to send appropriate replies. Once everyone realizes that there might not be a person on the other end, peremptory behavior online may become more common. We’ll likely learn to treat bots more like people. But, in the process, we may end up treating people more like bots.

Do read the whole thing.

What I’ve been reading

1. Tom Bissell, Apostle: Travels Among the Tombs of the Twelve. Fun, engaging, and informative, worthy of the “best of the year non-fiction” list.

2. China Miéville, Embassytown. The first of his novels that has clicked with me, perhaps because it is the one that comes closest to being a true novel of ideas, Heideggerian ideas in this case. A new prophecy is needed, and the nature of the new prophecy, like the old, will be shaped by language. Just accept that upon your first reading you won’t enjoy the first one hundred pages and you should at some point go back and read them again.

3. Yuri Herrara, Signs Preceding the End of the World. Sometimes considered Mexico’s greatest active writer, this novella draws upon the Juan Rulfo-Dante-Dia de los muertos tradition to create a convincing moral universe in 128 pages. I find this more vivid and arresting than Cormac McCarthy’s treatment of the other side of the border.

4. The Gene: An Intimate History, by Siddhartha Mukherjee. This book filled in a number of gaps in my knowledge, plus it is engaging to read. Overall it confirmed my impression of major advances in the science, but not matched by many medical products for general use.

The other books I read weren’t as good as these.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Are teaching evaluations biased against female instructors?

2. Ryan Avent has a book coming out in September.

3. Is this the worst debate I ever have read? No, but for a short while I thought it was.

4. It will receive more criticism when Trump does the same.

5. “Earlier this month, Ringling Bros. Circus retired all of their elephants.”

6. The China-Pakistan nexus and its strength.

7. Beckworth podcast with Selgin on monetary policy and the productivity norm.

Against Historic Preservation

Larry Summers asks:

How…could our society have regressed to the point where a bridge that could be built in less than a year one century ago takes five times as long to repair today?

As I wrote in Launching:

Our ancestors were bold and industrious–they built a significant portion of our energy and road infrastructure more than half a century ago. It would be almost impossible to build the system today. Unfortunately, we cannot rely on the infrastructure of our past to travel to our future.

Summers alludes to the regulatory thicket as a cause of the infrastructure slowdown but doesn’t have much to say about fixing the problem. Here’s a place to begin. Repeal all historic preservation laws. It’s one thing to require safety permits but no construction project should require a historic preservation permit. Here are three reasons:

First, it’s often the case that buildings of little historical worth are preserved by rules and regulations that are used as a pretext to slow competitors, maintain monopoly rents, and keep neighborhoods in a kind of aesthetic stasis that benefits a small number of people at the expense of many others.

Second, a confident nation builds so that future people may look back and marvel at their ancestor’s ingenuity and aesthetic vision. A nation in decline looks to the past in a vain attempt to “preserve” what was once great. Preservation is what you do to dead butterflies.

Ironically, if today’s rules for historical preservation had been in place in the past the buildings that some now want to preserve would never have been built at all. The opportunity cost of preservation is future greatness.

Third, repealing historic preservation laws does not mean ending historic preservation. There is a very simple way that truly great buildings can be preserved–they can be bought or their preservation rights paid for. The problem with historic preservation laws is not the goal but the methods. Historic preservation laws attempt to foist the cost of preservation on those who want to build (very much including builders of infrastructure such as the government). Attempting to foist costs on others, however, almost inevitably leads to a system full of lawyers, lobbying and rent seeking–and that leads to high transaction costs and delay. Richard Epstein advocated a compensation system for takings because takings violate ethics and constitutional law. But perhaps an even bigger virtue of a compensation system is that it’s quick. A building worth preserving is worth paying to preserve. A compensation system unites builders and those who want to preserve and thus allows for quick decisions about what will be preserved and what will not.

Some people will object that repealing historic preservation laws will lead to some lovely buildings being destroyed. Of course, it will. There is no point pretending otherwise. It will also lead to some lovely buildings being created. More generally, however, the logic of regulatory thickets tells us that we cannot have everything. As I argued in Launching:

There are good regulations and bad regulations and lots of debate over which is which. From an innovation perspective, however, this debate misses a key point. Let’s assume that all regulations are good. The problem is that even if each regulation is good, the net effect of all the regulations combined may be bad. A single pebble in a big stream doesn’t do much, but throw enough pebbles and the stream of innovation is dammed.

It’s time to blow the dam. Creative destruction requires some destruction.

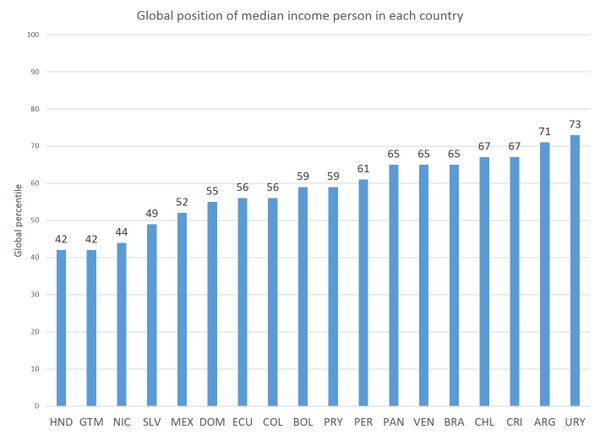

Uruguay fact of the day

Person with a median income in Uruguay is better-off than 73% of the world population.

That is from Branko Milanovic.

My worries about Singapore

Singapore is a well-run place by world standards, and has perhaps the world’s highest quality bureaucracy, yet right now the country faces a somewhat menacing constellation of silent risks, none of their own making:

1. It is possible that the role of the United States in the Pacific Ocean is rewritten rather suddenly. This could come about through either a Trump presidency, or a successful Chinese attempt to grab more in the South China Sea. Can you imagine a Singapore that had to court Japan and India rather than relying on the United States for protection? In this same world Japan is probably more militarized than in the status quo, and possibly even a nuclear power.

2. Singapore sovereign wealth funds and related institutions have been pulling in high returns since the 1970s. Yet the opportunities in both China and Singapore’s own real estate just aren’t there any more. They would be very lucky to pull in four percent a year looking forward. While fiscal risk is minimal, this will crimp expansion plans, especially if Singapore ends up needing to spend more on national defense.

3. It seems increasing pressure is being brought to bear on the Chinese currency yet again. China would like to lower rates to stimulate its economy, and the Fed is likely to raise rates at least once more this year. There is surely a chance that the renminbi simply snaps due to capital outflow. During the Asian currency crisis, the Singaporean dollar fell about twenty percent as a side effect of the turmoil elsewhere. Yet now China is much bigger than South Korea + Thailand + Indonesia were in 1997. Furthermore Singapore is much more of a financial and clearinghouse center. How insulated is Singapore from this China risk? Does anybody know? To what extent might a flow of capital into Singapore mitigate some of this risk?

4. Climate change could well lead to rising water levels for island nation Singapore. Investing in sea walls and other forms of protection could take what percent of gdp? The Dutch are already putting 0.5% of gdp a year into a fund for future water defense.

From this list, #2 and #4 are more likely problems, whereas #1 and #3 are more speculative, but by no means in the realm of science fiction. There is the possibility of a perfect storm from all four.

And yet think of how things must have looked in 1965. The Vietnam War was going badly, and most of the trends in Southeast Asia were negative. Chinese Communism was at its nadir with the Cultural Revolution. Indonesia had just massacred 500,000 citizens, many of them Chinese. Singapore itself had just been kicked out of Malaysia, an outcome which its key founders mostly opposed. There was not yet evidence that what later became “the Singapore model” was going to work, and even Japan was not yet an evident success. It was commonly believed that Singapore, Malaysia, or both might collapse into a kind of ethnic civil war. British military expenditures were about 20% of Singapore’s gdp, and it was widely understood that source of income would be going away. Somehow they managed, most of all with the aid of human capital and being in the right place at the right time.

Here is the Singapore Complaints Choir, one of my favorite music videos.

In any case, I am happy to be here once again. For dining, I recommend Sinar Pagi Nasi Padang, at Geylang Serai hawker centre, get the beef rendang. National Kitchen, in the new National Gallery is also very good for a more traditional kind of dining.