Month: June 2016

Art as a wartime investment the asset that is countercyclical

From a new Economic Journal article by Kim Oosterlinck:

During World War II, artworks significantly outperformed all alternative investments in Occupied France. With the surge in demand for portable and easy-to-hide (discreet) assets such as artworks and collectible stamps, prices boomed. This suggests that discreet assets may be viewed as crypto-currencies, demand for which varies depending on the environment and the need to hide value. Regarding art market valuation, this paper argues that while some economic actors derive significant utility from conspicuous consumption, others value the discretion offered by artworks. Motives for purchasing art may thus vary over time.

The pointer is from Kevin Lewis. And via Samir Varma, here is a new piece on how the returns to fine art have been overestimated.

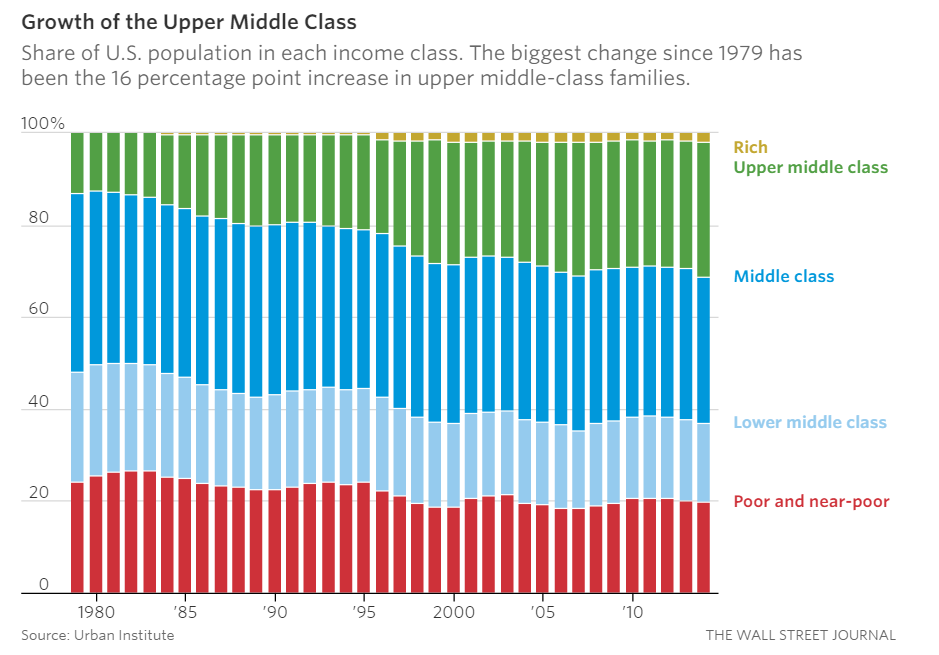

The Middle Class is Shrinking Because Many People are Getting Richer

Newspaper headlines trumpeted that the middle class is shrinking but to a large extent that is because people are moving into the upper middle class not because they are getting poorer. By one measure, the middle class has shrunk from 38% of the US population in 1980 to 32% today but at the same time the upper middle class has grown from 12% to 30% of the population today.

Josh Zumbrun at the WSJ has an excellent piece on new research from the (liberal-leaning) Urban Institute and elsewhere:

There is no standard definition of the upper middle class. Many researchers have defined the group as households or families with incomes in the top 20%, excluding the top 1% or 2%. Mr. Rose, by contrast, uses a more dynamic method similar to how researchers calculate the poverty rate, which allows for growth or shrinkage over time, and adjusts for family size.

Using Census Bureau data available through 2014, he defines the upper middle class as any household earning $100,000 to $350,000 for a family of three: at least double the U.S. median household income and about five times the poverty level. At the same time, they are quite distinct from the richest households. Instead of inheritors of dynastic wealth or the chief executives of large companies, they are likely middle-managers or professionals in business, law or medicine with bachelors and especially advanced degrees.

Smaller households can earn somewhat less to be classified as upper middle-class; larger households need to earn somewhat more.

Mr. Rose adjusts these thresholds for inflation back to 1979 and finds the population earning this much money has never been so large. One could quibble with his exact thresholds or with the adjustment that he uses for inflation. But using different measures of inflation, or using higher income thresholds for the upper-middle class, produces the same result: substantial growth among this group since the 1970s.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Interfluidity on the blockchain: “Nothing that has already been perfected is very interesting.”

2. What Chinese women think of Hillary Clinton: “One adjective: Endurance, cleaning up the mess of her husband.”

3. Why do islands induce dwarfism?

4. Physical principles for scalable neural recording.

5. Archaeologists uncover the massive naval bases of the ancient Athenians.

6. India to liberalize foreign investment (NYT). Since Modi took office, the reforms have not been so significant; in my view it is a mistake to think that the departure of Rajan indicates matters will get worse. He probably did all he could and in part the regime can allow him to leave for this reason. For further progress it may be necessary to install someone more “flexible.”

7. Lebron’s block: the stats and physics (HT: Alex T.).

China head transplant sentence of the day to ponder

Critics attribute such medical experimentation in China to national ambition, generous state funding, a utilitarian worldview that prioritizes results, and a lack of transparency and accountability to the outside world.

If that is the critics, I wonder what the defenders say! That concerns transplanting one person’s head onto the body of another. From that NYT article, the procedure still seems impossible. Nonetheless I am not sure the NYT’s articulation of the critical charges sounds as damning as many biomedical ethicists might wish to think…

What I’ve been reading

1. Andrej Svorencik and Harro Maas, editors, The Making of Experimental Economics: Witness Seminar on the Emergence of a Field. Transcribed dialogue on the origins and history of a field, including many of the key players including Vernon Smith and Charles Plott, among others. There should be a book like this — or better yet a web site — for every movement, major debate, new method, and school of thought.

2. Adam Kucharski, The Perfect Bet: How Science and Math are Taking the Luck Out of Gambling. The subtitle is an exaggeration, nonetheless this is an interesting topic and book. There is invariably a frustrating element to such an investigation, because the best schemes are hard to uncover or verify. Nonetheless have you not thought — as I have — that a determined, Big Data-crunching, super smart entity could in fact beat the basketball odds just ever so slightly?

3. Svetlana Alexievich, Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets. A good book, and a good introduction to her writing. I have to say though, I did not find this incredibly profound or original. Chernobyl is deeper and more philosophical.

4. Srinath Raghavan, India’s War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia. Consistently well-written and interesting, the title says it all.

Three useful country/topics books on Latin America are:

Lee J. Alston, Marcus Andre Melo, Bernardo Mueller, and Carlos Pereira, Brazil in Transition: Beliefs, Leadership, and Institutional Change.

Richard E. Feinberg, Open for Business: Building the New Cuban Economy.

Dickie Davis, David Kilcullen, Greg Mills, and David Spencer, A Great Perhaps?: Colombia: Conflict and Convergence. After Uruguay, is Colombia not the longest standing democracy in South America?

Monday assorted links

2. Them vs. us, but in Brexit demands, who exactly is the “us”?

3. Patrick Blanchfield, The Gun Control We Deserve. Recommended. And here is an alternative perspective on why so many people own AR-15s. Also recommended.

4. “In Guadalajara, Mexico, streets are named after artists, constellations, Aztec history and mythology, rivers, writers and botany. Imagination costs little, yet it remains rare.” Archaeology of street names.

5. “A political philosophy devoted to the pursuit of what we now consider ideal justice, and which seeks a “well-ordered society” based on this shared ideal, almost certainly will condemn us to a society based on an inferior view of justice. Political philosophy, I argue, has too long labored under the sway of theorists’ pictures of an ideally just society; we ought instead to investigate the characteristics of societies that encourage increasingly just arrangements.” That is from philosopher Gerald Gaus.

6. An explainer on the DAO attack. And a Reddit explainer.

7. Henry on The Age of Em. Robin responds, and more from Robin here.

The First Law — robot sentences to ponder

The robot administers a small pin prick at random to certain people of its choosing.

The tiny injury pierces the flesh and draws blood.

Mr Reben has nicknamed it ‘The First Law’ after a set of rules devised by sci-fi author Isaac Asimov.

He created it to generate discussion around our fear of man made machines. He says his latest device shows we need to prepare for the worst

‘Obviously, a needle is a minimum amount of injury, however – now that this class of robot exists, it will have to be confronted,’ Mr Reben said on his website.

Here is more, with pictures of (slightly) injured humans, via the excellent Mark Thorson.

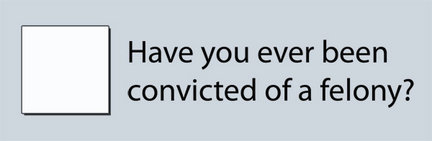

Ban the Box or Require the Box?

Ban the box policies forbid employers from asking about a criminal record on a job application. Ban the box policies don’t forbid employers from running criminal background checks they only forbid employers from asking about criminal history at the application/interview stage. The policies are supposed to give people with a criminal background a better shot at a job. Since blacks are more likely to have a criminal history than whites, the policies are supposed to especially increase black employment.

One potential problem with these laws is that employers may adjust their behavior in response. In particular, since blacks are more likely than whites to have a criminal history, a simple, even if imperfect, substitute for not interviewing people who have a criminal history is to not interview blacks. Employers can’t ask about race on a job application but black and white names are distinctive enough so that based on name alone, one can guess with a high probability of being correct whether an applicant is black or white. In an important and impressive new paper, Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr examine how employers respond to ban the box.

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr sent out approximately 15,000 fake job applications to employers in New York and New Jersey. Otherwise identical applications were randomized across distinctively black and white (male) names. Half the applications were sent just before and another half sent just after ban the box policies took effect. Not all firms used the box even when legal so Agan and Starr use a powerful triple-difference strategy to estimate causal effects (the black-white difference in callback rates between stores that did and did not use the box before and after the law).

Agan and Starr find that banning the box significantly increases racial discrimination in callbacks.

One can see the basic story in the situation before ban the box went into effect. Employers who asked about criminal history used that information to eliminate some applicants and this necessarily affected blacks more since they are more likely to have a criminal history. But once the applicants with a criminal history were removed, “box” employers called back blacks and whites for interviews at equal rates. In other words, the box leveled the playing field for applicants without a criminal history.

Employers who didn’t use the box did something simpler but more nefarious–they offered blacks fewer callbacks compared to otherwise identical whites, regardless of criminal history. Together the results suggest that employers use distinctively black names to statistically discriminate.

When the box is banned it’s no longer possible to cheaply level the playing field so more employers begin to statistically discriminate by offering fewer callbacks to blacks. As a result, banning the box may benefit black men with criminal records but it comes at the expense of black men without records who, when the box is banned, no longer have an easy way of signaling that they don’t have a criminal record. Sadly, a policy that was intended to raise the employment prospects of black men ends up having the biggest positive effect on white men with a criminal record.

Agan and Starr suggest one possible innovation–blind employers to names. I think that is the wrong lesson to draw. Agan and Starr look at callbacks but what we really care about is jobs. You can blind employers to names in initial applications but employers learn about race eventually. Moreover, there are many other margins for employers to adjust. Employers, for example, could simply start increasing the number of employees they put through (post-interview) criminal background checks.

Policies like ban the box try to get people to do the “right thing” by blinding people to certain types of information. But blinded people tend to use other cues to achieve their interests and when those other cues are less informative that often makes things worse.

Rather than ban the box a plausibly better policy would be to require the box. Requiring all employers to ask about criminal history would tend to hurt anyone with a criminal record but it could also level racial differences among those without a criminal record. One can, of course, argue either side of that tradeoff and that is my point.

More generally, instead of blinding employers a better idea is to change real constraints. At the same time as governments are forcing employers to ban the box, for example, they are passing occupational licensing laws which often forbid employers from hiring workers with criminal records. Banning the box and simultaneously forbidding employers from hiring workers with criminal records illustrates the incoherence of public policy in an interest-group driven system.

Ban the box is another example of good intentions gone awry because the man of system tries to arrange people as if they were pieces on a chessboard, without understanding that:

…in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder. (Adam Smith, ToMS)

Addendum 1: The Agan and Starr paper has much more of interest. Agan and Starr, find, for example, evidence of discrimination going beyond that associated with statistical discrimination and crime. In particular, whites are more likely to be hired in white neighborhoods and blacks are more likely to be hired in black neighborhoods.

Addendum 2: Agan was my former student at GMU. Her undergraduate paper (!), Sex Offender Registries: Fear without Function?, was published in the Journal of Law and Economics.

How much does English proficiency help you in economics?

William W. Olney has a newly published paper on that topic, and it seems it helps a good deal:

This article investigates whether the global spread of the English language provides an inherent advantage to native English speakers. This question is studied within the context of the economics profession, where the impact of being a native English speaker on future publishing success is examined. English speakers may have an advantage because they are writing in their native language, the quality of writing is a crucial determinant of publishing success, and all the top economics journals are published in English. Using a ranking of the world’s top 2.5% of economists, this article confirms that native English speakers are ranked 100 spots higher (better) than similar non-native English speakers. A variety of extensions examine and dispel many other potential explanations.

“Similar” is a tricky word! How similar can a Frenchman be? I am not sure, but it does seem that growing up in the Anglo-American world may — language aside — be more conducive to patterns of thought which predict success in…the Anglo-American world. Nonetheless this is an interesting investigation, even if I am not entirely convinced. Note also that economics blogging is predominantly an Anglo-American enterprise, but I view that too as more about “mentality” than language per se.

For the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Hermance, Switzerland

I am here to give a talk on randomized control trials, a public choice perspective. Angus Deaton and Josh Angrist are among the other speakers, along with many people in the medical field. The first question, not quite resulting from a controlled experiment, is whether this setting, on Lake Geneva, improves or worsens my mood…

Geneva notes

This is still the land of the $76 veal chop, and that is not at Michelin-starred restaurants. You will do better by seeking out ethnic food on and around Rue de Monthoux, which is in center city and concludes right by the lake. At an Indian-Iranian restaurant just off this street, Royal India, I had perhaps the best fesenjan in memory.

Due to lost bank secrecy, international banks are leaving Geneva, and Swiss watch exports are falling. The view of the lake is still beautiful, and some of the lake shore real estate now seems to be empty. The swans are still all white, however.

Barbier-Mueller is piece for piece one of the higher quality museums in the world, mostly African and Oceanic items, and currently they have a good show on media of exchange with artistic qualities.

Center city now seems to be at least fifty percent immigrants, and I am not referring to the numerous French and Germans who settle in Switzerland. This was not what I was expecting the first time I saw Geneva in 1985. It is a livelier city, but it still radiates that old, vague sense of dullness.

Sunday assorted links

1. Charles W. Cooke is the new editor of National Review On-Line.

2. Photos of Venezuela, some story too.

3. Two Arabs, a Berber, and a Jew: I just ordered my copy.

4. Erik Dahmen was a significant Swedish economist (pdf).

5. Does filling in some actual numbers resolve the Fermi paradox?

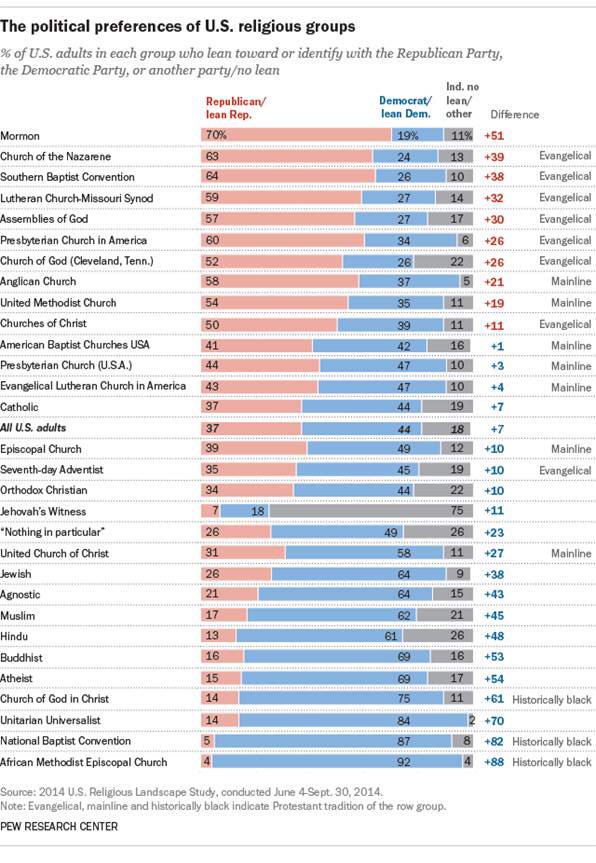

6. The politics of religion, an interesting chart:

Do I think Robin Hanson’s “Age of Em” actually will happen?

A reader has been asking me this question, and my answer is…no!

Don’t get me wrong, I still think it is a stimulating and wonderful book. And if you don’t believe me, here is The Wall Street Journal:

Mr. Hanson’s book is comprehensive and not put-downable.

But it is best not read as a predictive text, much as Robin might disagree with that assessment. Why not? I have three main reasons, all of which are a sort of punting, nonetheless on topics outside one’s areas of expertise deference is very often the correct response. Here goes:

1. I know a few people who have expertise in neuroscience, and they have never mentioned to me that things might turn out this way (brain scans uploaded into computers to create actual beings and furthermore as the dominant form of civilization). Maybe they’re just holding back, but I don’t think so. The neuroscience profession as a whole seems to be unconvinced and for the most part not even pondering this scenario.

2. The people who predict “the age of Em” claim expertise in a variety of fields surrounding neuroscience, including computer science and physics, and thus they might believe they are broader and thus superior experts. But in general claiming expertise in “more” fields is not correlated with finding the truth, unless you can convince people in the connected specialized fields you are writing about. I don’t see this happening, nor do I believe that neuroscience is somehow hopelessly corrupt or politicized. What I do see the “Em partisans” sharing is an early love of science fiction, a very valuable enterprise I might add.

3. Robin seems to think the age of Em could come about reasonably soon (sorry, I am in Geneva and don’t have the book with me for an exact quotation). Yet I don’t see any sign of such a radical transformation in market prices. Even with positive discounting, I would expect backwards induction to mean that an eventual “Em scenario” would affect lots of prices now. There are for instance a variety of 100-year bonds, but Em scenarios do not seem to be a factor in their pricing.

Robin himself believes that market prices are the best arbiter of truth. But which market prices today show a realistic probability for an “Age of Em”? Are there pending price bubbles in Em-producing firms, or energy companies, just as internet grocery delivery was the object of lots of speculation in 1999-2000? I don’t see it.

The one market price that has changed is the “shadow value of Robin Hanson,” because he has finished and published a very good and very successful book. And that pleases me greatly, no matter which version of Robin is hanging around fifty years hence.

Addendum: Robin Hanson responds. I enjoyed this line: “Tyler has spent too much time around media pundits if he thinks he should be hearing a buzz about anything big that might happen in the next few centuries!”

Where do extreme right-wing anti-immigration views come from?

Very often they are passed down father to son. Here is a recent paper by Avdeenko and Siedler:

This study analyzes the importance of parental socialization on the development of children’s far right-wing preferences and attitudes towards immigration. Using longitudinal data from Germany, our intergenerational estimates suggest that the strongest and most important predictor for young people’s right-wing extremism are parents’ right-wing extremist attitudes. While intergenerational associations in attitudes towards immigration are equally high for sons and daughters, we find a positive intergenerational transmission of right-wing extremist party affinity for sons, but not for daughters. Compared to the intergenerational correlation of other party affinities, the high association between fathers’ and sons’ right-wing extremist attitudes is particularly striking.

Here is a sentence from the paper:

Young adults whose parents were very concerned about immigration to German during their childhood years have a 27 percentage point (60 percent) higher likelihood of also expressing strong concerns about immigration as young adults.

This of course should make you less confident of your anti-immigrant views, if indeed you hold them. Similarly, the intergenerational transmission of particular religious beliefs is also a strong reason not to be very confident in them. If you get your religious beliefs from your parents and other relatives, through whatever mechanism, rather than from God, well…why are your parents a more reliable source of knowledge about this question than anyone else’s parents?

Are cultural omnivores actually stuck-up sticky bits?

Poking big holes in long-held assertions, Goldberg and his colleagues at Stanford and Yale universities analyzed millions of Yelp and Netflix reviews to reveal that people considered the most culturally adventurous are actually the most resistant to experiences perceived as “crossing the line.”

That is, those dubbed “cultural omnivores” — because they eat Thai for lunch, play bocce ball after work, and stream a French film that night — are the very ones opposed to mixing it up. No hummus on their hot dogs, forget about spaghetti Westerns, and do not mention Switched-On Bach. Those offerings are not considered culturally authentic. They are a hodgepodge to which these folks would likely wrinkle their collective noses — as they did in 1968 when Wendy (nee’ Walter) Carlos electrified J.S. Bach. Today’s cultural elites approve only if the experience is authentic, which means eating pigs’ feet at a Texas barbecue passes the test and slathering a taco with tahini does not.

“We find these people hate the most atypical offerings,” says Goldberg, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “They can pretend to be the most open, but it turns out they are not. By being multicultural, they are the most conservative and the most resistant to changes to the status quo.”

Or should we just call it good taste?

Here is the Katherine Conrad article, via the excellent Dan Wang.