Month: May 2017

Why I don’t believe in God

R., a Catholic and loyal MR reader, emails me:

I would be interested in a post explaining why you *don’t* believe in (some form of) God.

Not long ago I outlined what I considered to be the best argument for God, and how origin accounts inevitably seem strange to us; I also argued against some of the presumptive force behind scientific atheism. Yet still I do not believe, so why not? I have a few reasons:

1. We can distinguish between “strange and remain truly strange” possibilities for origins, and “strange and then somewhat anthropomorphized” origin stories. Most religions fall into the latter category, all the more so for Western religions. I see plenty of evidence that human beings anthropomorphize to an excessive degree, and also place too much weight on social information (just look at how worked up they get over social media), so I stick with the “strange and remain truly strange” options. I don’t see those as ruling out theism, but at the end of the day it is more descriptively apt to say I do not believe, rather than asserting belief.

2. The true nature of reality is so strange, I’m not sure “God” or “theism” is well-defined, at least as can be discussed by human beings. That fact should not lead you to militant atheism (I also can’t define subatomic particles), but still it pushes me toward an “I don’t believe” attitude more than belief. I find it hard to say I believe in something that I feel in principle I cannot define, nor can anyone else.

2b. In general, I am opposed to the term “atheist.” It suggests a direct rejection of some specific beliefs, whereas I simply would say I do not hold those beliefs. I call myself a “non-believer,” to reference a kind of hovering, and uncertainty about what actually is being debated. Increasingly I see atheism as another form of religion.

3. Religious belief has a significant heritable aspect, as does atheism. That should make us all more skeptical about what we think we know about religious truth (the same is true for politics, by the way). I am not sure this perspective favors “atheist” over “theist,” but I do think it favors “I don’t believe” over “I believe.” At the very least, it whittles down the specificity of what I might say I believe in.

4. I am struck by the frequency with which people believe in the dominant religions of their society or the religion of their family upbringing, perhaps with some modification. (If you meet a Wiccan, don’t you jump to the conclusion that they are strange? Or how about a person who believes in an older religion that doesn’t have any modern cult presence at all? How many such people are there?)

This narrows my confidence in the judgment of those who believe, since I see them as social conformists to a considerable extent. Again, I am not sure this helps “atheism” either (contemporary atheists also slot into some pretty standard categories, and are not generally “free thinkers”), but it is yet another net nudge away from “I believe” and toward “I do not believe.” I’m just not that swayed by a phenomenon based on social conformity so strongly.

That all said I do accept that religion has net practical benefits for both individuals and societies, albeit with some variance. That is partly where the pressures for social conformity come from. I am a strong Straussian when it comes to religion, and overall wish to stick up for the presence of religion in social debate, thus some of my affinities with say Ross Douthat and David Brooks on many issues.

5. I am frustrated by the lack of Bayesianism in most of the religious belief I observe. I’ve never met a believer who asserted: “I’m really not sure here. But I think Lutheranism is true with p = .018, and the next strongest contender comes in only at .014, so call me Lutheran.” The religious people I’ve known rebel against that manner of framing, even though during times of conversion they may act on such a basis.

I don’t expect all or even most religious believers to present their views this way, but hardly any of them do. That in turn inclines me to think they are using belief for psychological, self-support, and social functions. Nothing wrong with that, says the strong Straussian! But again, it won’t get me to belief.

6. I do take the William James arguments about personal experience of God seriously, and I recommend his The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature to everybody — it’s one of the best books period. But these personal accounts contradict each other in many cases, we know at least some of them are wrong or delusional, and overall I think the capacity of human beings to believe things — some would call it self-deception but that term assumes a neutral, objective base more than is warranted here — is quite strong. Presumably a Christian believes that pagan accounts of the gods are incorrect, and vice versa; I say they are probably both right in their criticisms of the other.

7. I see the entire matter of origins as so strange that the “transcendental argument” carries little weight with me — “if there is no God, then everything is permitted!” We don’t have enough understanding of God, or the absence of God, to deal with such claims. In any case, the existence of God is no guarantee that such problems are overcome, or if it were such a guarantee, you wouldn’t be able to know that.

Add all that up and I just don’t believe. Furthermore, I find it easy not to believe. It doesn’t stress me, and I don’t feel a resulting gap or absence in my life. That I strongly suspect is for genetic reasons, not because of some intellectual argument I or others have come up with. But there you go, the deconstruction of my own belief actually pushes me somewhat further into it.

To sum it all up, agnosticism is pretty easy to argue for, and it gets you a lot closer to “not believing” than “believing.”

My Conversation with Raj Chetty

Yes, the Raj Chetty. Here is the transcript and podcast. As far as I can tell, this is the only coverage of Chetty that covers his entire life and career, including his upbringing, his early life, and the evolution of his career, not to mention his taste in music. Here is one bit:

COWEN: Now your father, he’s a well-known economist, and he studied econometrics with Arnold Zellner at University of Wisconsin. At what age did he start talking to you about Bayesian econometrics?

CHETTY: [laughs]

COWEN: Which is one of his fields, right?

CHETTY: That’s right, my dad did a lot of early work in Bayesian econometrics with Arnold Zellner, and the academic environment was something I grew up with since I was a kid. I’m the last person in my family to publish a paper. My sisters are also in academia on the medical and bio side. Whether it’s statistics or thinking about scientific questions or thinking about how to change things in the world, that’s the environment in which I grew up from the youngest of ages.

We also discuss his famous papers on kindergarten teachers, social mobility, and the other topics he is best known for working on, including tax salience and corporate dividends. My favorite part is where Chetty explains what I call “the Raj Chetty production function,” namely why he has been part of so many very successful papers, but that is hard to excerpt. There is also this:

COWEN: In music, the group the Piano Guys, speaking of Mormons. Overrated or underrated?

CHETTY: Underrated. I love the Piano Guys.

COWEN: Why?

CHETTY: I think the Piano Guys are great in terms of doing renditions of popular songs.

COWEN: Not too triumphalist? Do you mean the major chords?

CHETTY: Maybe in some cases, but I like them.

COWEN: Bhindi or okra. Overrated or underrated?…

Self-recommending, if there ever was such a thing.

Understanding the Great Depression

The latest video in our Principles of Macroeconomics course at MRUniversity covers Understanding the Great Depression. I like this video a lot. It starts by illustrating the great fall in aggregate demand using the AD-AS model but also looks at the dust bowl, the Smoot-Hawley tariff and the National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA). The section on the tariff beautifully illustrates the argument that trade is like a technology that allows us to almost-magically transform one good into another. And the final section on the awful NRA has some great visuals.

Is preventive care worth the cost?

And here is yet another paper suggesting that medical care, or at least some forms of it, has relatively low marginal value. The subtitle of this one is “Evidence from Mandatory Checkups in Japan” and the authors are Toshiaki Iizuka, Katsuhiko Nishiyama, Brian Chen, and Karen Eggleston. Here is the abstract:

Using unique individual-level panel data, we investigate whether preventive medical care triggered by health checkups is worth the cost. We exploit the fact that biomarkers just below and above a threshold may be viewed as random. We find that people respond to health signals and increase physician visits. However, we find no evidence that additional care is cost effective. For the “borderline type” (“pre-diabetes”) threshold for diabetes, medical care utilization increases but neither physical measures nor predicted risks of mortality or serious complications improve. For efficient use of medical resources, cost effectiveness of preventive care must be carefully examined.

Here is the NBER link.

Pharmaceutical Reciprocity for Canada

If pharmaceutical reciprocity is a good idea for the United States, it’s a great idea for smaller countries. Indeed, this is mostly what happens in practice, even if not by law, since smaller countries can’t afford or justify the expensive US process. Fred Roeder of the Montreal Economic Institute makes the case for reciprocity in Canada:

…reciprocal recognition of drug approval authorities on both sides of the Atlantic would incentivize Canadian, European and American authorities to spend less time and money conducting parallel reviews. If the HPFB, the FDA or the EMA approved a drug, patients in Canada, Europe and America would have immediate access to it — increasing consumers’ choice as new drugs are offered to patients faster and more affordably, with less red tape driving up costs.

A reduction in approval time can be a win-win for patients and firms because a decrease in approval time is an increase in effective patent length without an actual increase in patent length. The numbers below are optimistic, but the idea that streamlining approval can increase profits and stimulate investment is correct:

These market-oriented reforms would not benefit not only consumers, but the pharmaceutical companies as well, expanding the timespan of the patents. On average, new drugs have a mere 10 to 14 years of patent protection remaining by the time they are sold to consumers after they have successfully jumped over all the government hurdles. Streamlining the drug approval process would increase the timespan of patented drugs on the market by 50 to 70 per cent.

Roeder also mentions Bart Madden’s important book Free to Choose Medicine. (For those who don’t know, I am proud to be the Bartley J. Madden chair in economics at Mercatus at GMU.)

On the macroeconomics of Trump’s budget

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

What’s also striking is that, if the Trump budget can work at all, the spending cuts are probably not needed. It would suffice to cut taxes only, and allow the economy to grow out of an even-greater budget deficit. In this regard, the Trump budget reflects a deep incoherence, and it inconsistently mixes various optimistic and pessimistic scenarios. If the spending cuts are required for fiscal stability, then we probably shouldn’t be doing the tax cuts.

This framework allows us to pinpoint the huge and, I would say, excessively dangerous gamble in Trump’s budget. There is no guarantee that the growth rate of the economy remains higher than the government’s borrowing rate. It is common in American history that government borrowing rates run 5 percent or higher, and the aging of the American population, or perhaps an unexpected catastrophe, such as a war, could lower the growth rate. 1 And once a government becomes addicted to borrowing, it is hard to shake the habit, as subsequent tax increases damage economies.

Do read the whole thing, which focuses on g vs. r…

The fiscal future of the West, the culture that is inheritance

Heaven forbid that people of means should pay for their own health care, what a sensible idea this was:

Last week, she [Theresa May] came up with a flawed but constructive answer to the crisis of funding in social care. The elderly would finance their care out of their own estate upon death. The upper limit on their contribution would go but they could keep £100,000 for their children. In the mixed metaphors that proliferate in politics, a floor would replace a cap.

The idea turned old age into a high-stakes game of chance — die suddenly and your estate would go untouched, contract dementia and it would shrivel over time — but it confronted voters with the principle that things must be paid for and challenged the Conservative cult of inheritance. Mrs May made it central to her election manifesto. Her self-image as a firm leader hinged on her fidelity to this brave, contentious idea.

A few days of popular disquiet and the cap is back.

That is from Janan Ganesh at the FT. Solve for the fiscal equilibrium!

Tuesday assorted links

1. Justin Fox on West Virginia and the limits of its comeback.

2. The new Hypermind NGDP futures market.

3. Should the federal government cap the research grant indirect cost rate at 10 percent?

4. The blind baseball announcer.

5. NYT update on the weakening of IRBs for the social sciences.

6. “Reports said her job is herding goats and cattle, walking some 10-15km every day.“

*Art Collecting Today*

The author is Doug Woodham, and the subtitle is Market Insights for Everyone Passionate About Art.

I liked everything in this book, note that the author is a Ph.d economist, has been a partner for McKinsey and also held a major position for Christie’s.

That said, I felt it should have done much more to explain how art is used for money laundering, and also tax arbitrage through donations at inflated prices, based on corrupt appraisals. Those are big reasons why art prices for highly liquid works have boomed so much over the last few decades. Arguably art markets are some of the most corrupt markets in the Western world today.

Measured by the number of Instagram followers, the three biggest artists in the world today are Banksy, JR, and Shepard Fairey.

For deceased artists, the Twitter hashtags game is won by Warhol, Picasso, Dali, and van Gogh, with da Vinci, Monet, and Michelangelo coming next.

Of the 25 highest priced artists in the world today, as measured by auction sales, 8 of them are Chinese. How many of them can you say you are familiar with? On that list are Cui Ruzhuo, Fan Zeng, Zhou Chunya, Zhang Xiaogang, He Jiaying, Huang Yongyu, Liu Wei, and Ju Ming.

Here is more by Zhou Chunya.

Oscar Wilde once said: “When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss art. When artists get together for dinner, they discuss money.”

I can gladly recommend this book, noting it tells only part of the story.

Is low expected market volatility good for the world but bad for America?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit, the optimistic part:

When observing the evolution of market prices in reaction to Trump, I am currently left with a mix of very optimistic and very pessimistic sentiments.

First, the European Union, and not the U.S., really does remain the center of Western civilization. The underappreciated good news is that European growth rates are edging up, the euro as a currency appears to have a more secure future, and Brexit, though I view it as a major mistake for the U.K., is not pulling apart the broader European project. The refugee crisis has stabilized, and right-wing populist parties are not taking over Europe. I see that (legitimate) concerns about the impact of Trump are distracting many people from these quite positive developments.

Second, I now view many asset classes as at least partially dependent on Chinese capital, but I’m not so afraid of that capital going away, as those positions have built-in hedges. If China does well, the flow of Chinese capital will continue. If China does poorly, capital will leave China rather rapidly and seek out foreign investments, and that too gives non-Chinese markets a fair degree of protection. China’s highly leveraged position may be precarious internally, but the West has a built-in hedge, namely that bad times for China still send more capital our way, at least for a while. That’s another piece of security that we have been distracted from seeing, though I’m not sure it is good news for China itself.

If you were wondering what to make of low expected volatility in markets, it’s typically worth looking at which asset prices have been volatile. I have two nominations: Chinese corporate bonds and Chinese commodity prices, both of which have fluctuated considerably with changing expectations about Chinese deleveraging. But those have not created a broader crisis of volatility, which is consistent with the above story about how the world as a whole has been growing economically safer. Furthermore, the ongoing growth of emerging economies implies more global diversification over the long run for both trade and investment.

Do read the whole thing.

The culture that is Shanghai

A storm has erupted in China over its hyper-competitive education system, after oversubscribed private schools in Shanghai sought to filter intake by conducting tests and checks not only on prospective pupils but also parents and grandparents.

That is from Emily Feng at the FT, via Dan Wang.

Monday assorted links

1. How to make America great again.

2. “We want to give the impression of every aspect of dinosaur life.”

3. “Habitual sub eater may move lunch spot because of Tonawanda resident’s gripe.”

4. Church of England fund is top world performer (FT).

5. Pittsburgh is no longer so thrilled with Uber driverless cars (NYT).

6. The forthcoming sand shortage? (New Yorker).

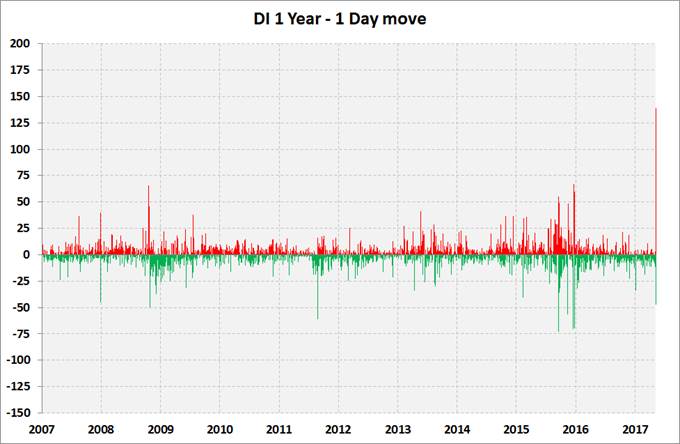

I am hearing reports of a ten-sigma event in Brazil

The Trump administration, lookism, and the Saudis

I’ve been guilty of this too, and I apologize. It strikes me that it has become politically acceptable among some of the high status people in my Twitter feed to make fun — if only implicitly — of the ugly, idiosyncratic, puzzled, sweaty, or otherwise mockable images sometimes presented by members of the Trump administration.

I’ve also seen a tendency to use images to play on some of the ruling Saudis as fitting stereotypes of sinister or perhaps comical, or some combination of the two. At the very least, “orientalism” is making a comeback, and with some of the people who have been objecting to Trump’s own stereotypes.

I do not see these as positive developments. It is inevitable that, to some extent, we judge people by their looks, and in some instances it may be practical and indeed necessary as well. That said, I doubt if it is a good idea to publicly mock the ugly and the mockable for being ugly and mockable. Even if they are evil, or doing the world harm.

Many people (rightly) criticized Trump’s campaign imitation and mockery of what seemed to be a spastic individual. Let’s say Trump had done the same imitation of a spastic who had been convinced of robbery and murder. Would that have been better? Well, maybe better but still not good. Don’t mock the looks, even of wrongdoers, even if those are looks of stupidity or boorishness, and of course members of the Trump administration have not been so convicted.

What if there are some people born looking sinister (by our standards), but are perfectly nice and friendly? Or say there were witches, and witches were bad, and most witches had long, crooked noses, but some other people did too. Should we caricature/criticize witches for this appearance?

Furthermore, the standards for ugly and mockable are in fact not always so clear, and trying to cement them in with our mockery is problematic.

This also should be a lesson as to how easily people can slip into enjoying racist, sexist, and otherwise objectionable memes. Returning to the Saudis, it is especially easy to use this particular photo because stereotypes of Arabs still are permissible in some parts of American discourse:

Would that photo have been retweeted so many times if it simply had looked like a normal Western bureaucratic meeting? And yes, you can use this photo to show Trump is a hypocrite, relative to his earlier pronouncements about the Saudis, but of course the picture communicates much more, namely that the Saudis have a very different and sometimes strange-looking (to us) culture.

We should not hesitate to criticize what we think is wrong. But criticizing the appearance of various wrongs, as embodied in the looks of various people, is going a step further. Don’t let the wrongdoers distract you from the reality that your use of images may be promoting an unjust generalization, or in fact mocking people for non-objectionable cultural elements. In other words, the use of images may be promoting “lookism.”

This is one of the most serious problems with photos on Twitter, namely that we are not good enough to use them carefully. Right now, the unjust philosophy of lookism is on a rampage, bigly.

Uber sentences to ponder

Uber seems to be moving to a system where some rides cost more than others, even in the absence of surge pricing:

An Uber spokesperson assured Axios that pricing has nothing to do with a rider’s perceived level of income, past rides, or any individual characteristics.

So far only for UberPool in limited locations, I also am interested in this as a test of whether social media can strike down price discrimination. What will the prices be contingent upon? Traveling to a starred Michelin restaurant? Why then use UberPool? Here is further (but still incomplete) information, and yet more here. How long will it take people to figure out the implied rules for contingent prices? Are we these days capable of accepting any such rules as fair?

The pointer is from Matthew Kahn.