Month: June 2018

More on the Education Tax

In my post, The Education Tax Reduces Inequality and the Incentive to Work, I illustrated how the high cost of college combined with income based pricing have turned education pricing into a tax with potentially significant effects on work and savings incentives. David Henderson pointed me to a paper by Martin Feldstein in 1992, College Scholarship Rules and Private Saving which states the issues very well.

This paper examines the effect of existing college scholarship rules on the incentive to save. The analysis shows that families that are eligible for college scholarships face “education tax rates” on capital income of between 22 percent and 47 percent in addition to regular slate and federal income taxes. The scholarship rules also impose an annual tax on previously accumulated assets. Through the combination of the implied tax on capital income and the associated tax on previously accumulated assets, the scholarship rules that apply to a middle-income family reduce the value of an extra dollar of accumulated assets by 30 cents in four years. A similar family with two children who attend college in succession will see an initial dollar of assets reduced to 50 cents. Such capital levies of 30 to 50 percent are a strong incentive not to save for college expenses but to rely instead on financial assistance and even on regular market borrowing, Moreover, since any funds saved for retirement are also subject to these education capital levies. the scholarship rules discourage retirement saving as well as saving for education. The empirical analysis developed here, based on the 1986 Survey of Consumer Finances, implies that these incentives do have a powerful effect on the actual accumulation of financial assets. More specifically, the estimated parameter values imply that the scholarship rules induce a typical household with a head aged 45 years old, with two precollege children, and with income of $40,000 a year to reduce accumulated financial assets by $23,124 approximately 50 percent of what would have been accumulated without the adverse effect of the scholarship rules.

Dick and Edlin made a similar point in 1997 but, as far as I can tell, there have been only a handful of papers on this issue since that time. The cost of college, however, is about twice as high today as in the 1980s and price discrimination is much more extensive so the effects are likely larger today.

Is carbon capture underrated?

Siphoning carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere could be more than an expensive last-ditch strategy for averting climate catastrophe. A detailed economic analysis published on 7 June suggests that the geoengineering technology is inching closer to commercial viability.

The study, in Joule, was written by researchers at Carbon Engineering in Calgary, Canada, which has been operating a pilot CO2-extraction plant in British Columbia since 2015. That plant — based on a concept called direct air capture — provided the basis for the economic analysis, which includes cost estimates from commercial vendors of all of the major components. Depending on a variety of design options and economic assumptions, the cost of pulling a tonne of CO2 from the atmosphere ranges between US$94 and $232. The last comprehensive analysis of the technology, conducted by the American Physical Society in 2011, estimated that it would cost $600 per tonne.

That is by Jeff Tollefson in Nature, via Brad Plumer. Of course this is potentially very significant news.

How much is deep sea fishing subsidized?

While the ecological impacts of fishing the waters beyond national jurisdiction (the “high seas”) have been widely studied, the economic rationale is more difficult to ascertain because of scarce data on the costs and revenues of the fleets that fish there. Newly compiled satellite data and machine learning now allow us to track individual fishing vessels on the high seas in near real time. These technological advances help us quantify high-seas fishing effort, costs, and benefits, and assess whether, where, and when high-seas fishing makes economic sense. We characterize the global high-seas fishing fleet and report the economic benefits of fishing the high seas globally, nationally, and at the scale of individual fleets. Our results suggest that fishing at the current scale is enabled by large government subsidies, without which as much as 54% of the present high-seas fishing grounds would be unprofitable at current fishing rates. The patterns of fishing profitability vary widely between countries, types of fishing, and distance to port. Deep-sea bottom trawling often produces net economic benefits only thanks to subsidies, and much fishing by the world’s largest fishing fleets would largely be unprofitable without subsidies and low labor costs. These results support recent calls for subsidy and fishery management reforms on the high seas.

Emphasis added, that is by Enric Sala, et.al., via Anecdotal.

Thursday assorted links

1. Black clergy debate payday loans.

2. “Much of the art that leaves North Korea actually travels to a small village outside Tuscany…” And it is shipped using DHL.

Can privatization solve Ethiopia’s problems?

Here is a new paper by Ermyas Amelga, excerpt:

Privatization will not just solve the GTP’s financing problem, a worthy enough accomplishment in its self, but would also help address macroeconomic problems. These include funding/driving aggregate demand, financing aggregate investment, solving the foreign exchange shortage, rebalancing the balance of payments, dampening inflation and reviving general economic activity. May seem improbable but its not.

In the context of the huge financing needs to fulfill the plans under the GTP, privatization represents an excellent means of cashing out on the accumulated net worth of Ethiopia’s SOE’s. Indeed, there is arguably no more justifiable use of this accumulated net worth than spending it on the GTP that the government itself believes is worthy of supreme sacrifice from all corners of society.

This paper is a very good introduction to both Ethiopia’s corporate problems and also their fiscal problems. Privatization is not entirely fashionable these days, but the current situation in Ethiopia presents perhaps the strongest case for it. So if your initial reaction is “Ah privatization, that is the failed strategy that China rightly rejected”…you are making exactly the same mistake made by many privatization proponents in the 1990s. Ethiopia is starved for revenue, foreign exchange, and the country needs more private sector involvement/

And lo and behold, Ethiopia has in fact just announced a major plan to privatize many parts of some of the major state-owned companies.

By the way, I wish to thank Chris Blattman for an introduction to Ermyas and also for valuable ideas and information related to Ethiopia.

Brutalism in Singapore

Is this article evidence that we (I?) are living in a simulation? Or did the editors of The Economist place it as an Easter Egg for me?:

The building, which was once called a “vertical slum” by a Singaporean legislator, is a densely packed mix of residential and commercial units. Along with People’s Park in Chinatown (pictured), which has been praised by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, it is among a handful of Brutalist buildings that were built in a surge of architectural confidence after the country became independent in 1965. They are particularly adored by those who love concrete, as well as bold and wacky colours.

Modernist buffs have started to fret that many of these Brutalist buildings will soon be gone. In February one of them, Pearl Bank, once the highest residential tower in Singapore, was sold for S$728m ($544m) to CapitaLand, one of Asia’s largest real-estate developers. The company plans to demolish the yellow horseshoe structure and build a “high-rise residential development” of 800 flats in its place.

Here is the full story, here is a related article from Malay Mail.

Advice for possible and wanna-bee book writers

Adam Ozimek asks me:

Bleg for

@tylercowen, don’t think I asked this before but maybe I did…. advice for economists and other social scientists planning on writing a book (I’m not planning, just curious for the future)

Let me pull out those social scientists whose disciplines expect them to write books for tenure and promotion, because those are quite different cases. I’ll start with a few simple questions:

1. Should you write a book? You will always have something better to do, and thus IQ and conscientiousness are not necessarily your friends in this endeavor. And you are used to having them as your friends in so much of what you do.

2. Should anyone, other than historians (broadly construed), write a book?

3. Will you make more money from an excellent email newsletter?

4. How about some YouTube lectures? You don’t have to mention the lobster.

5. Consistently good columnists are hard to come by, and believe it or not blogs still exist.

6. Twitter is now up to 280 characters, photos too, maybe more to come.

7. Will your book idea still be fresh, given the long lags in the writing and publication cycle? Won’t DT have done so much more between now and then? Don’t his tweets obliterate interest in your book?

8. In advance, try to predict the price they will charge for your book. Also try to predict the percentage of the reading public — and I mean those who bought your book — who will get past the first ten percent.

One good reason to write a book is when you have the feeling you cannot do anything else without getting the book out of your system. In that sense, you can think of the lust to write books as a kind of disability.

Another good reason to write a book is so you can do the rounds on the podcast circuit. It doesn’t matter if no one reads your book, provided you are invited to do the right podcasts. Wouldn’t you rather talk to people anyway?

Yet another possible reason to write a book is the desire to get on “the speaker’s circuit,” noting that most book topics won’t help you with this at all. You had better be good.

Bryan Caplan is perhaps the most natural “social science book writer” I have met, besides myself of course. Not only does he want people to agree with him, he insists that they agree with him for the right reasons.

If you’re still game, start by writing every single day. No exceptions. Sooner or later, you will have something, and then you can write another one.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Those new service sector jobs: “Florida’s best-known industries include citrus, seafood and selling tacky souvenirs to tourists. But there’s one booming Florida industry that hardly ever gets a mention from the Chamber of Commerce folks.

Mermaids.

All over the state there are now scores of women — and a few men — who regularly pull on prosthetic tails and pretend to be those mythical creatures made popular by Hans Christian Anderson and Walt Disney. Some do it for fun, but quite a few are diving into it as a business, charging by the hour to appear at everything from birthday parties to political events.”

2. Robin Hanson Age of Em paperback is now out.

3. Ethiopia agrees to abide by its earlier peace and boundary agreement with Eritrea (NYT, big news).

My Conversation with David Brooks

David was in top form, and I feel this exchange reflected his core style very well, here is the audio and transcript.

We covered why people stay so lonely, whether the Amish are happy, life in Italy, the Whig tradition, the secularization thesis, the importance of covenants, whether Judaism or Christianity has a deeper reading of The Book of Exodus, whether Americans undervalue privacy, Bruce Springsteen vs. Bob Dylan, whether our next president will be a boring manager, and last but not least the David Brooks production function.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Walt Whitman, not only as a poet, but as a foundational thinker for America. Overrated or underrated?

BROOKS: I’d have to say slightly overrated.

COWEN: Tell us why.

BROOKS: I think his spirit and his energy sort of define America. His essay “Democratic Vistas” is one of my favorite essays. It captures both the vulgarity of America, but the energy and especially the business energy of America. But if we think the rise of narcissism is a problem in our society, Walt Whitman is sort of the holy spring there.

[laughter]

COWEN: Socrates, overrated or underrated?

BROOKS: [laughs] This is so absurd.

[laughter]

BROOKS: With everybody else it’s like Breaking Bad, overrated or underrated? I got Socrates.

[laughter]

BROOKS: I will say Socrates is overrated for this reason. We call them dialogues. But really, if you read them, they’re like Socrates making a long speech and some other schmo saying, “Oh yes. It must surely be so, Socrates.”

[laughter]

BROOKS: So it’s not really a dialogue, it’s just him speaking with somebody else affirming.

COWEN: And it’s Plato reporting Socrates. So it’s Plato’s monologue about a supposed dialogue, which may itself be a monologue.

BROOKS: Yeah. It was all probably the writers.

And on Milton Friedman:

BROOKS: I was a student at the University of Chicago, and they did an audition, and I was socialist back then. It was a TV show PBS put on, called Tyranny of the Status Quo, which was “Milton talks to the young.” So I studied up on my left-wing economics, and I went out there to Stanford. I would make my argument, and then he would destroy it in six seconds or so. And then the camera would linger on my face for 19 or 20 seconds, as I tried to think of what to say.

And it was like, he was the best arguer in human history, and I was a 22-year-old. It was my TV debut — you can go on YouTube. I have a lot of hair and big glasses. But I will say, I had never met a libertarian before. And every night — we taped for five days — every night he took me and my colleagues out to dinner in San Francisco and really taught us about economics.

Later, he stayed close to me. I called him a mentor. I didn’t become a libertarian, never quite like him, but a truly great teacher and a truly important influence on my life and so many others. He was a model of what an academic economist should be like.

Recommended. (And I actually thought David did just fine in that early exchange with Friedman.)

The Education Tax Reduces Inequality and the Incentive to Work

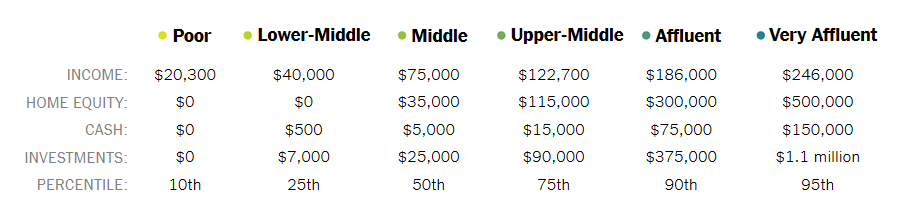

At the NYTimes David Leonhardt breaks families down into six income classes from the poor to the very affluent, defined as follows:

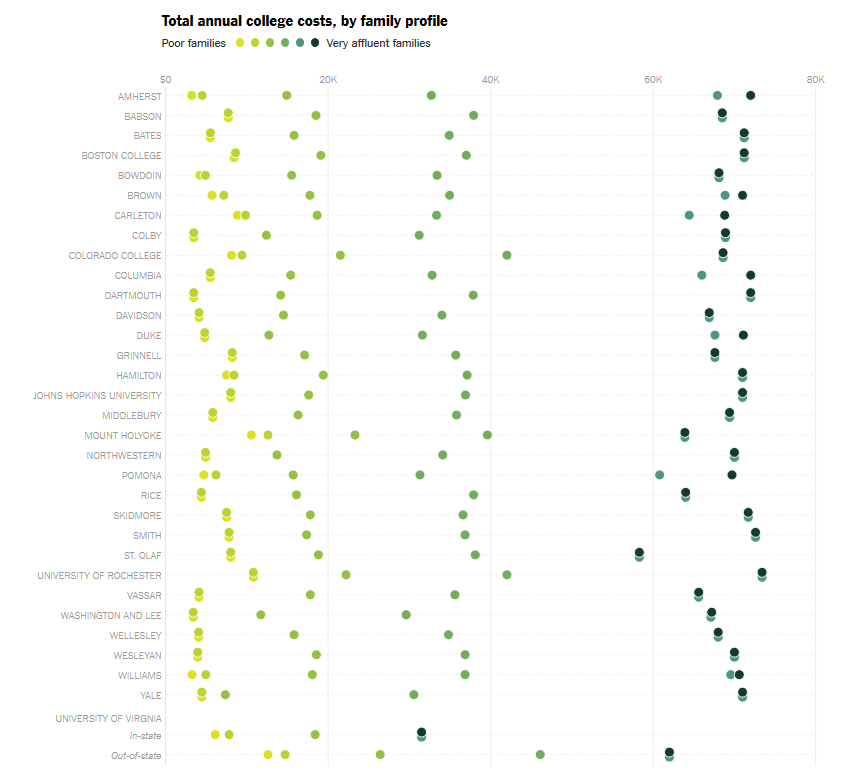

Using a tuition calculator he then estimates tuition (including room and board) by income class at 32 colleges and universities (see below–the darker dots indicate the richer income classes). At many private colleges and universities it is not unusual for some students to be paying $70,000 per year while others pay less than $5,000, for exactly the same education. (Tyler and I provide some similar data on college price discrimination in Modern Principles.) Leonhardt’s point is that a poor student can afford an expensive education and might actually save money by going to an elite private university rather than to a state college.

Price discrimination in education has two other, less recognized, consequences. It reduces income inequality and it reduces the incentive to work. If every firm charged twice as much to someone who earned twice as much, there would no consumption inequality despite high measured income inequality. The rich don’t pay more than the poor when they buy the same basket of goods at the grocery store but they do pay much more for the same education.The Affluent pay approximately $70 thousand for education at the colleges Leonhardt examines while the Upper-Middle pay about half that. The effect on inequality is significant for families with kids in college. An Affluent person is 52% richer than an Upper-Middle income person (186/122=1.52) but an Affluent person with a kid in college is only 33% richer than an Upper-Middle income person with a kid in college (((186-70)/(122-35)=1.33). Shockingly, an Affluent person with two kids in college is actually poorer than an Upper-Middle income person with two kids in college! ((186-140)/(122-70)=0.88.

Under income-based pricing the education tax becomes an income tax with all the negative aspects of income taxes on behavior such as diminished work incentives. Let’s take a closer look at an Upper-Middle income parent earning $122 thousand per year. If this parent gets a promotion or takes on extra work that bumps their salary by $64 thousand, they move from being Upper-Middle income to Affluent. At least on paper. At an income of $122 thousand the parent will be paying approximately $35 thousand to send their child to college but at $186 thousand they will have to pay $70 thousand for the same college so the increase in salary of $64 thousand is an effective increase of only $29 thousand. If the Upper-Middle income parent has two children in college, earning more money actually results in a net loss. For an Upper-Middle income family with two kids spaced in age a few years apart the education tax could be a very severe work disincentive for up to a decade.

The education tax is a peculiar tax as it is often paid to private organizations rather than to the government but it is still a tax and for those of Upper-Middle income the education tax is a very significant tax.

The consequences of the education tax on inequality and work incentives are neither well studied nor well understood.

Long-run Effects of Lottery Wealth on Psychological Well-being

Here is a new NBER working paper from Erik Lindqvist, Robert Östling, and David Cesarini:

We surveyed a large sample of Swedish lottery players about their psychological well-being and analyzed the data following pre-registered procedures. Relative to matched controls, large-prize winners experience sustained increases in overall life satisfaction that persist for over a decade and show no evidence of dissipating with time. The estimated treatment effects on happiness and mental health are significantly smaller, suggesting that wealth has greater long-run effects on evaluative measures of well-being than on affective ones. Follow-up analyses of domain-specific aspects of life satisfaction clearly implicate financial life satisfaction as an important mediator for the long-run increase in overall life satisfaction.

In other words, it is good to have more money.

The Interpersonal Sunk-Cost Effect

Christopher Olivola

Psychological Science, forthcomingAbstract:

The sunk-cost fallacy — pursuing an inferior alternative merely because we have previously invested significant, but nonrecoverable, resources in it — represents a striking violation of rational decision making. Whereas theoretical accounts and empirical examinations of the sunk-cost effect have generally been based on the assumption that it is a purely intrapersonal phenomenon (i.e., solely driven by one’s own past investments), the present research demonstrates that it is also an interpersonal effect (i.e., people will alter their choices in response to other people’s past investments). Across eight experiments (N = 6,076) covering diverse scenarios, I documented sunk-cost effects when the costs are borne by someone other than the decision maker. Moreover, the interpersonal sunk-cost effect is not moderated by social closeness or whether other people observe their sunk costs being “honored.” These findings uncover a previously undocumented bias, reveal that the sunk-cost effect is a much broader phenomenon than previously thought, and pose interesting challenges for existing accounts of this fascinating human tendency.

Barter history teaching markets in everything?

The governments of Myanmar and Israel signed an agreement on Monday that will promote Holocaust education in Myanmar and allow each country to determine how it is depicted in the other’s history textbooks.

The agreement provides for a variety of joint initiatives that feature in standard agreements Israel has signed with other countries, such as encounters between educators and students from both countries and joint study trips. The two countries will also “cooperate to develop programs for the teaching of the Holocaust and its lessons of the negative consequences of intolerance, racism, Anti-Semitism and xenophobia as a part of the school curriculum in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.”

Here is the unusual story, via a retweet from the excellent Chris Blattman.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Gary Marcus with a critical appraisal of Deep Learning.

2. Short Faroe Islands video. And underwater tunnels revolutionize the Faroe Islands. And postal service in the Faroe Islands: “Kristina runs a small guesthouse on the island. She tells me how her children, the last to leave the island, “kept the postal service in business” with their eBay and Amazon purchases.” Recommended.

4. I’m cramming for finals by watching someone else study (WSJ).

Alesund notes

Alesund, Norway is one of the most beautiful small cities in Europe. The setting is picture-perfect, and much of the architecture was redone in 1904-1905 in Art Nouveau style, due to a fire that burned down the previous wooden structures. The Art Nouveau murals in the town church deserve to be better known.

This time around, Norway seems vaguely affordable. The food is “good enough,” especially if you like cod. Dark chocolate ice cream is hard to come by. Driving to the puffins takes 3-4 hours, though they are not always to be seen.