Is Facebook causing anti-refugee attacks in Germany?

Here is the key result, as summarized by the NYT:

Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by about 50 percent.

Here is the underlying Müller and Schwarz paper. They consider 3,335 attacks over a two-year period in Germany. But I say no, their conclusion has not been demonstrated. Where to start?

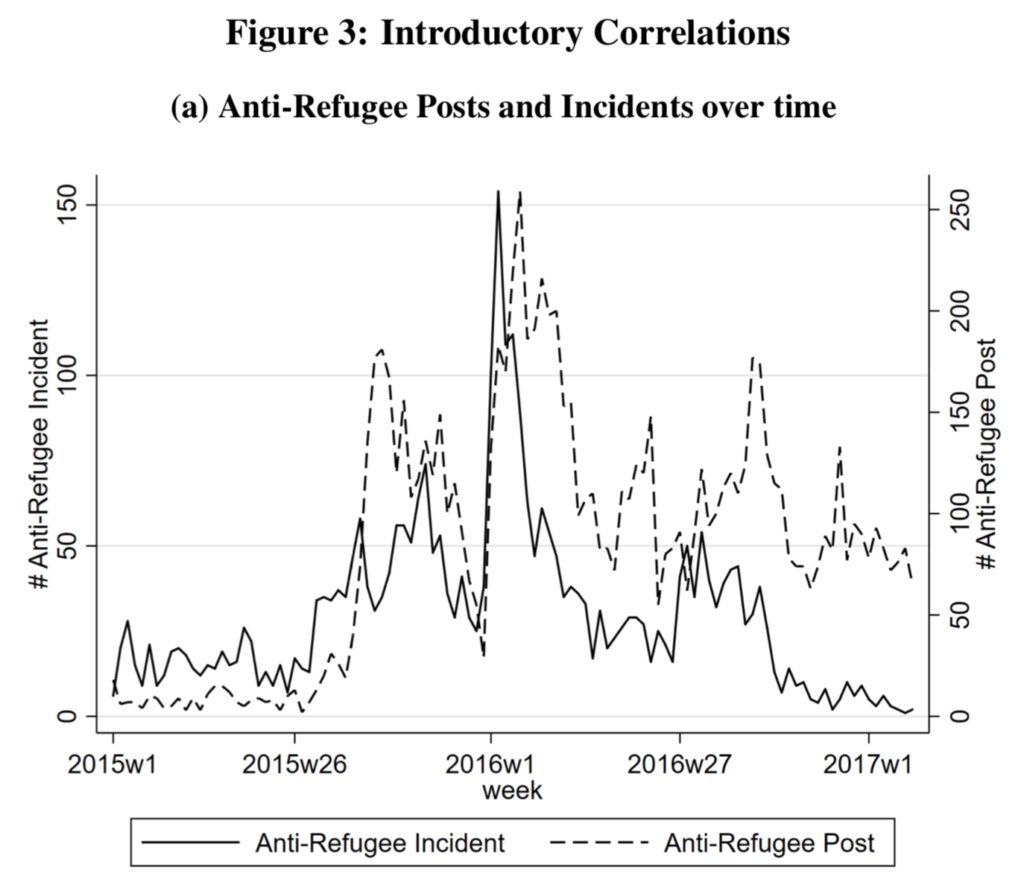

Here is one picture showing a key correlation:

That looks pretty strong, doesn’t it? Nein! That is not how propaganda works, as an extensive literature in sociology and political psychology will indicate. That is how it looks when you measure what is essentially the same variable — or its effects — two different ways. For instance, that very big spike in the middle of the distribution? As Ben Thompson has pointed out, it represents the New Year’s harassment attacks in Cologne. Maybe that caused both Facebook activity and other attacks to spike at the same time? Will you mock me if I resort to the “blog comment cliche” that correlation does not show causation?

That looks pretty strong, doesn’t it? Nein! That is not how propaganda works, as an extensive literature in sociology and political psychology will indicate. That is how it looks when you measure what is essentially the same variable — or its effects — two different ways. For instance, that very big spike in the middle of the distribution? As Ben Thompson has pointed out, it represents the New Year’s harassment attacks in Cologne. Maybe that caused both Facebook activity and other attacks to spike at the same time? Will you mock me if I resort to the “blog comment cliche” that correlation does not show causation?

To continue with the excellent Ben Thompson (he is worth paying for!), the identification method used in the paper is suspect, and he focuses on this quotation from the authors:

In our setting, the share of a municipality’s population that use the AfD Facebook page is an intuitive proxy for right-wing social media use; however, it is also correlated with differences in a host of observable municipality characteristics — most importantly the prevalence of right-wing ideology. We thus attempt to isolate the local component of social media usage that is uncorrelated with right-wing ideology by drawing on the number of users on the “Nutella Germany” page. With over 32 million likes, Nutella has one of the most popular Facebook pages in Germany and therefore provides a measure of general Facebook media use at the municipality level. While municipalities with high Nutella usage are more exposed to social media, they are not more likely to harbor right-wing attitudes.

The whole result rests on assumptions about Nutella? What if you used likes for Zwetschgenkuchen? Has a robustness test been done? Was a simple correlation not good or not illustrative enough? I’ll stick with the simple hypothesis that some municipalities have both more Facebook usage, due to high AfD membership, and also more attacks on refugees, and furthermore both of those variables rise in tense times. AfD is the German party with the strongest presence on Facebook, I am sorry to say.

You will note by the way that within Germany the Nutella page has only verifiable 21,915 individual interactions, including likes (32 million is the global number of Nutella likes…die Deutschen are not that nutty), and that is distributed across 4,466 municipal areas. (If you are confused, see p.12 in the paper, which I find difficult to follow and I suspect that represents the confusion of the authors.) That should make you more worried yet about the Nutella identification strategy. They never tell us what they would have without Nutella, a better tasting sandwich I would say.

I also would note the broader literature on propaganda once again. Consider the research of Markus Prior: “…evidence for a causal link between more partisan messages and changing attitudes or behaviors is mixed at best.” These Facebook results are simply far outside of what we normally suppose to be true about human responsiveness — so maybe the company is undercharging for its ads!

Ben adds:

I am bothered by the paper’s robustness section in two ways: first, every single robustness test confirmed the results. To me that does not suggest that the initial result must be correct; it suggests that the researchers didn’t push their data hard enough. There is always a test that fails, and that is a good thing: it shows the boundaries of what you have learned. Second, there were no robustness tests applied to one of the more compelling pieces of evidence, that Internet and Facebook outages were correlated with a reduction in violence against refugees. This is particularly unfortunate because in some ways this evidence works against the filter bubble narrative: after all, the idea is the filter bubbles change your reality over time, not that they suddenly inspire you to action out of the blue.

The authors do present natural experiments from Facebook and internet outages. They find that “…for a given level of anti-refugee sentiment, there are fewer attacks in municipalities with high Facebook usage during an internet outage than in municipalities with low Facebook usage without an outage.” (p.28). Again I find that confusing, but I note also that “internet outages themselves…do not have a consistent negative effect on the number of anti-refugee sentiments.” That is the simple story, and it appears to exonerate Facebook. pp.28-30 then present a number of interaction effects and variable multiplications, but I am not sure what to conclude from the whole mess. I’m still expecting internet outages to lower the number of attacks, but they don’t.

Even if internet or Facebook outages do have a predictive effect on attacks in some manner, it likely shows that Facebook is a communications medium used to organize gatherings and attacks (as the telephone once might have been), not, as the authors repeatedly suggest, that Facebook is somehow generating and whipping up and controlling racist sentiment over time. Again, compare such a possibility to the broader literature. There is good evidence that anti-semitic violence across German regions is fairly persistent, with pogroms during the Black Death predicting synagogue attacks during the Nazi time. And we are supposed to believe that racist feelings dwindle into passivity simply because the thugs cannot access Facebook for a few days or maybe a week? By the way, in their approach if there is an internet outrage, mobile devices do not in Germany pick up the slack.

I’d also like to revisit the NYT sentence, cited above, and repeated many times on Twitter:

Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by about 50 percent.

That sounds horrible, but it is actually a claim about variation across municipalities, not a claim about the absolute importance of the internet. The authors also reported a very different and perhaps more relevant claim to the Times:

…this effect drove one-tenth of all anti-refugee violence.

I would have started the paper with that sentence, and then tried to estimate its robustness, without relying on Nutella.

As it stands right now, you shouldn’t be latching on to the reported results from this paper.