Month: October 2018

Quote of the Day

The state-the machinery and power of the state-is a potential resource or threat to every industry in the society. With its power to prohibit or compel, to take or give money, the state can and does selectively help or hurt a vast number of industries…The central tasks of the theory of economic regulation are to explain who will receive the benefits or burdens of regulation, what form regulation will take, and the effects of regulation upon the allocation of resources.

Regulation may be actively sought by an industry, or it may be thrust upon it. A central thesis of this paper is that, as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.

Stigler, George J. 1971. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” Bell Journal of Economics Spring: 137–46.

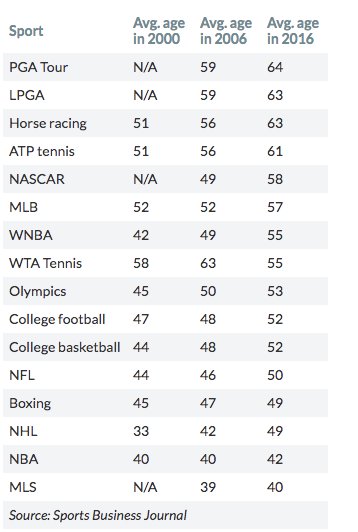

The television sports audience is aging

Here is the source link, via the excellent Michael Nielsen. And Michael notes: “…the audience for sport is aging less fast than for prime time tv; but faster than the US population as a whole.”

Kenyan hospital markets in everything

The Kenyatta National Hospital is east Africa’s biggest medical institution, home to more than a dozen donor-funded projects with international partners — a “Center of Excellence,” says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The hospital’s website proudly proclaims its motto — “We Listen … We Care” — along with photos of smiling doctors, a vaccination campaign and staffers holding aloft a gold trophy at an awards ceremony.

But there are no pictures of Robert Wanyonyi, shot and paralyzed in a robbery more than a year ago. Kenyatta will not allow him to leave the hospital because he cannot pay his bill of nearly 4 million Kenyan shillings ($39,570). He is trapped in his fourth-floor bed, unable to go to India, where he believes doctors might help him…

The hospitals often illegally detain patients long after they should be medically discharged, using armed guards, locked doors and even chains to hold those who have not settled their accounts. Mothers and babies are sometimes separated. Even death does not guarantee release: Kenyan hospitals and morgues are holding hundreds of bodies until families can pay their loved ones’ bills, government officials say.

Dozens of doctors, nurses, health experts, patients and administrators told The Associated Press of imprisonments in hospitals in at least 30 other countries, including Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, China and Thailand, Lithuania and Bulgaria, and others in Latin America and the Middle East.

Here is the full story by Maria Cheng, via Daniel Lippman.

My interview with Pioneer

Short, and mostly about boyhood, here is one bit:

If you became really good at something (physics, programming, art, music), how exactly did you first get hooked?

Learning is fun. I found that social sciences are a good vehicle for learning things all the time. That got me hooked. It made my travel more salient, and it enriched the time I spent with music and the arts. It helped me make sense of people, too. All that at once. That was a pretty potent brew, and it still is.

What are some weird things you worked on or did as a teenager?

These days, what’s weird? I play chess intensively for four years, ages 10 to 14. Then I studied economics for the rest of my life. Arguably I was less weird as a teenager than I am today. What’s weird is that I haven’t “matured” into a less intensive course of study.

Here is the full link, here is a link to Pioneer, a new venture capital enterprise to discover the “lost Einsteins.” That may be you, so go apply. Here is a Pioneer list of some specific projects of interest.

Saturday assorted links

1. Is this the beginning of the World Wide Wall? (related to Emergent Ventures, also). Recommended.

2. My parents give me 28k a year.

4. Profile of Bruno Latour (NYT).

5. Annapurna Devi has passed away (NYT).

Toward a theory of optimal personality?

If you are too conscientious, you might experience undue stress during a negative performance review. Or being too agreeable is correlated with lower salary levels, especially for men. And surely too much extroversion and too much openness are possible too?

Rolf Degen reproduces a few relevant paragraphs from a new paper. The work is by Nathan T. Carter, Joshua D. Miller, and Thomas A. Widiger, here is one excerpt from their abstract:

…researchers have only recently begun to uncover evidence that extreme standing on “normal” or “desirable” personality traits might be maladaptive…many more people possess optimal personality-trait levels than previously thought…

I don’t quite agree with that, though I wouldn’t, would I? I think they are overrating normality. The notion that “weirdos are bad” seems to me longstanding, and one of the most durable human intuitions, not something that researchers have only started to realize. In a world with growing division of labor, and greater accountability (in the private sector, at least), extreme traits would seem to be rising in social value. And perhaps some of that return can be captured as private value too — Silicon Valley anybody?

Overall, I still think that “falling short” on say either conscientiousness or openness is undesirable for most though not all individuals. How can conscientiousness ever be bad, you might be wondering? Well, if the world is underproducing people with unusual interests and inclinations, more conscientiousness might make “more weirdos” a harder outcome to achieve. For instance, conscientiousness, with respect to obligations toward broader society, might keep many people more conformist. That said, there still are many people who would do better to get up in the morning and go to work, one manifestation of conscientiousness.

Agreeableness is the trait that remains a hard to define black box. Cooperativeness is often good, though simple deference to the opinions of others, without critical examination, is often bad. When I hear “agreeableness” discussed as a formal personality trait, the possible clash between those two (and other) underlying features of agreeableness seems to receive insufficient attention.

Here is a previous MR Post on related issues.

Data mining is not infinitely powerful

To say the least:

Suppose that asset pricing factors are just data mined noise. How much data mining is required to produce the more than 300 factors documented by academics? This short paper shows that, if 10,000 academics generate 1 factor every minute, it takes 15 million years of full-time data mining. This absurd conclusion comes from rigorously pursuing the data mining theory and applying it to data. To fit the fat right tail of published t-stats, a pure data mining model implies that the probability of publishing t-stats < 6.0 is ridiculously small, and thus it takes a ridiculous amount of mining to publish a single t-stat. These results show that the data mining alone cannot explain the zoo of asset pricing factors.

That is from a new paper by Andrew Y. Chen at the Fed.

Hobo Economicus

We collect data on hundreds of panhandlers and the passersby they encounter at Metrorail stations in Washington, DC. Panhandlers solicit more actively when they have more human capital, when passersby are more responsive to solicitation, and when passersby are more numerous. Panhandlers solicit less actively when they compete. Panhandlers are attracted to Metrorail stations where passersby are more responsive to solicitation and to stations where passersby are more numerous. Across stations, potential-profit per panhandler is nearly equal. Most panhandlers use pay-what-you-want pricing. These behaviors are consistent with a simple model of rational, profit-maximizing panhandling.

That is the new paper by Peter T. Leeson and R. August Hardy.

Friday assorted links

1. Francis Bacon and machine learning.

2. Fat Cats in The New Yorker.

3. Top 100 albums of the last ten years? By Quietus, a highly intelligent source.

4. South Korea will not allow its citizens to smoke pot in Canada.

5. Interview with Stephen Sondheim.

6. How to judge tech companies, recommended. By Patrick McKenzie. “You might sensibly read these heuristics and think “Hmm, you seem to over-focus on speed. Aren’t quality, price, etc also really important?” These questions don’t *really* test for speed. They test for *repeatable competence at scale*, which is another thing entirely.”

Liveblogging the Bloomberg session on AI

Noah Feldman is moderator, Noah Smith and Justin Fox and Leonid Bershidsky and Shira Ovide and Dina Bass are presenting…you will find my live-blogging in the comments section of this post. Just keep on refreshing for the updates.

Livestream is here:

The culture and polity that is Seattle, Washington

Washington is at the top of “the terrible 10” states with the most regressive state and local tax systems, according to a report released this month by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

“These states ask far more of their lower- and middle-income residents than of their wealthiest taxpayers,” according to the institute.

This isn’t new news. My colleague Gene Balk wrote about the subject in April, highlighting a report from the Seattle-based Economic Opportunity Institute. That report found Washington taxation hardest on the poor, with Seattle the worst offender.

That is from Jon Talton, via Mike Rosenberg.

Interview with Chad Syverson

Interesting and substantive throughout, here is one bit:

Syverson: In general, we think companies that do a better job of meeting the needs of their consumers at a low price are going to gain market share, and those that don’t, shrink and eventually go out of business. The null hypothesis seems to be that health care is so hopelessly messed up that there is virtually no responsiveness of demand to quality, however you would like to measure it. The claim is that people don’t observe quality very well — and even if they do, they might not trade off quality and price like we think people do with consumer products, because there is often a third-party payer, so people don’t care about price. Also, there is a lot of government intervention in the health care market, and governments can have priorities that aren’t necessarily about moving market activity in an efficient direction.

Amitabh Chandra, Amy Finkelstein, Adam Sacarny, and I looked at whether demand responds to performance differences using Medicare data

. We looked at a number of different ailments, including heart attacks, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and hip and knee replacements. In every case, you see two patterns. One is that hospitals that are better at treating those ailments treat more patients with those ailments. Now, the causation can go either way with that. However, we also see that being good at treating an ailment today makes the hospital big tomorrow.

Second, responsiveness to quality is larger in instances where patients have more scope for choice. When you’re admitted through the emergency department, there’s still a positive correlation between performance and demand, but it’s even stronger when you’re not admitted through the emergency department — in other words, when you had a greater ability to choose. Half of the people on Medicare in our data do not go to the hospital nearest to where they live when they are having a heart attack. They go to one farther away, and systematically the one they go to is better at treating heart attacks than the one nearer to their house.

What we don’t know is the mechanism that drives that response. We don’t know whether the patients choose a hospital because they have previously heard something from their doctor, or the ambulance drivers are making the choice, or the patient’s family tells the ambulance drivers where to go. Probably all of those things are important.

It’s heartening that the market seems to be responsive to performance differences. But, in addition, these performance differences are coordinated with productivity — not just outcomes but outcomes per unit input. The reallocation of demand across hospitals is making them more efficient overall. It turns out that’s kind of by chance. Patients don’t go to hospitals that get the same survival rate with fewer inputs. They’re not going for productivity per se; they’re going for performance. But performance is correlated with productivity.

All of this is not to say that the health care market is fine and we have nothing to worry about. It just says that the mechanisms here aren’t fundamentally different than they are in other markets that we think “work better.”

Here is the full interview, via Patrick Collison.

Which comics are accused of joke theft?

Why might observers label one social actor’s questionable act a norm violation even as they seem to excuse similar behavior by others? To answer this question, I use participant-observer data on Los Angeles stand-up comics to explore the phenomenon of joke theft. Informal, community-based systems govern the property rights pertaining to jokes. Most instances of possible joke theft are ambiguous owing to the potential for simultaneous and coincidental discovery. I find that accusations are not strongly coupled to jokes’ similarity, and enforcement depends mainly on the extent to which insiders view the comic in question as being authentic to the community. Comics who are oriented toward external rewards, have a track record of anti-social behavior, and exhibit lackluster on-stage craft are vulnerable to joke theft accusations even in borderline cases because those inauthentic characteristics are typical of transgressors. Vulnerability is greatest for comics who enjoy commercial success despite low peer esteem. Authenticity protects comics because it reflects community-based status, which yields halo effects while encouraging relationships predicated on respect. In exploring accusations of joke theft and their outcomes, this study illustrates how norms function more as framing devices than as hard-and-fast rules, and how authenticity shapes their enforcement.

That is from “No Laughter among Thieves: Authenticity and the Enforcement of Community Norms in Stand-Up Comedy,” by Patrick Reilly, from the American Sociological Review.

For the pointer I thank Siddharth Muthukrishnan.

The Year that Words Were First Used in Print

In the year that I was born, 1966, some words which were used for the first time in print were:

cryonics, art deco, assault weapon, ROM, biocontainment, hot button, kung fu, meth, male-pattern baldness, multitasking, multiorgasmic, Medicaid, number cruncher, paperless, street smarts, ranch dressing, z-score

I would have guessed that many of these terms were older.

New words in recent years are ico, manspreading, utility token and aquafaba (?).

All this is according to the Merriam-Webster Time Traveler.

Hat tip: Paul Kedrosky.