Month: June 2019

Libra and remittances

Dante Disparte, as interviewed by Ben Thompson ($$, but you should subscribe to Ben):

One example is the use case of international money transfers or remittances. Globally, the remittance cash flow is projected to be about $715 billion in 2019, and on average…you are seeing between seven and ten percent of transfer costs, and in some instances much higher than that in the teens. For a product and an outcome from the sender and receiver point of view, that is not only very slow, it often takes a few days to clear on the receiving end, it is [extremely expensive]. There are direct payment rails that are just technology powered that do a lot in terms of advancing efficiency, but pre-blockchain it would have been very, very hard to conceive of a network of international payments that could do that at near zero cost instantaneously while at the same time not sacrificing the type of ledgering and transaction information that would enable the world to begin to do that securely. So that would be one amazing use case that could put billions and billions of dollars back into the market by eliminating as many of these fees as possible, while at the same time putting billions of dollars into the hands of people around the world in real time.

Here is my current understanding of Libra/Calibra, at least within this particular context, noting again that my understanding may be wrong or incomplete. These transfers would not go through the current banking system as we know it, but rather through a blockchain with say 100 or so (quite legitimate) participants enforcing some kind of “proof of stake” standard. Some form of “proof of stake-equivalent of mining fees” would have to be paid, either explicitly or implicitly, and those arguably could be much lower than current remittance costs, noting that the actual operation of proof of stake in this setting remains to me murky. Still, it would largely avoid the current mining fees associated with Bitcoin. On net, one is trading in the current regulatory and clearing and Western Union branch costs for these future proof of stake costs. Do you think the Libra Association can run a proof of stake system for less say than $100 billion?

“But don’t you have to convert your Libras back into mainstream fiat currencies?” Well, maybe you might, but that is simply the cost of showing up at the relevant financial institutions and claiming redemption. Those costs also could be much lower than the current fees associated with remittances. What is sent through the blockchain network simply can be Libras, as I understand it, with varying assumptions on how much people will hold Libras rather than converting them.

To use a historical analogy, think of this as substituting “the transfer of paper claims to gold” for “claims to gold,” but in a one hundred percent reserves setting. It can be (and indeed was) much cheaper to send around the paper than the gold, and yet the paper still was a claim to the gold. The Libra is a kind of parallel, redeemable currency, legally not within standard banking systems, but still redeemable in terms of mainstream fiat currencies which are within standard banking systems. “Create a synthetic claim which can be traded more cheaply” would be my version of the ten-word slogan.

Another slightly wordier slogan might be: “let’s actually separate the means of payment from the medium of exchange by creating a new synthetic asset, because those two things actually should not be the exact same asset.”

Of course it still remains to be seen in which countries regulators will allow this to happen. How persuasive is the promise of one hundred percent reserves? I don’t mean to speak for Libra/Calibra here, but I believe they are suggesting (or implying?) that the proof of stake system for making and validating transfers could in essence enforce relevant regulations against money laundering, illegal transfers, and the like.

It is a quite separate (but possible) claim to believe that libras could serve as an effective medium of exchange at a retail level, and perhaps I will cover that in a separate post. That would mean that both the medium of exchange and means of payment should be new and different assets, a much stronger claim.

Here are my earlier questions about Libra, with responses.

Chengdu bleg

Your suggestions are most welcome, this short trip will follow the time in Taipei. Where in particular should I eat and what should I eat? I have been to Chengdu once before, four years ago.

Wednesday assorted links

1. John Taylor’s on-line summer economics principles class.

2. Which countries and regions trust scientists the most and least? (Uzbekistan first, Gabon comes in last.)

3. Simaro Lutumba has passed away.

How to fight neo-Nazis is beer supply really so inelastic in the short run?

Residents in Ostritz, Germany, banned together recently to stick it to a group of neo-Nazis in the only way they know how — by buying up all the town’s beer before they do.

More than 200 crates were scooped up by locals as they prepared for the arrival of “Shield and Sword” (SS) festival attendees, who have a notorious reputation for being far-right activists obsessed with Nazi culture, the BBC reports…

Residents began buying up all the booze because they were worried that festivalgoers would try to purchase some at local stores and supermarkets, according to the BBC, which cited interviews with the German newspaper Bild.

Here is the full article, via Ian Bremmer.

Will price transparency in health care markets work?

The scholarship suggests that more transparency in health care could backfire, causing prices to rise instead of fall…

“I don’t know if you have had the misfortune of having health economists tell you about Danish cement,” said Amanda Starc, an associate professor of strategy at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern, one of several scholars who mentioned a paper with a punny name: “Government-Assisted Oligopoly Coordination? A Concrete Case.”

“Everybody loves the Danish concrete example!” said Matthew Grennan, an assistant professor of health care management at Wharton, who has studied the effects of price transparency on hospital purchases.

The Danish government, in an effort to improve competition in the early 1990s, required manufacturers of ready-mix concrete to disclose their negotiated prices with their customers. Prices for the product then rose 15 percent to 20 percent.

The reason, scholars concluded, is that there were few manufacturers competing for business. Once companies knew what their competitors were charging, it was easy for them to all raise their prices in concert. They could collude without the sort of direct communication that would make such behavior illegal. It wasn’t easy for new companies to undercut the existing ones, because the material hardens so fast that you can’t ship it far…

Research on gasoline markets has likewise found that publicizing prices appears to enable collusion in places where there are only a few competitors. But among more plentiful Israeli supermarkets, a database of prices appears to have lowered them.

Scholars at the Federal Trade Commission put out a paper in 2015 cautioning against the kind of price transparency that the president is embracing.

That is all from Margot Sanger-Katz (NYT). And via Ilya Novak, here is a recent piece by Zach Y. Brown:

This paper examines whether information frictions in the market for medical procedures lead to higher prices and price dispersion in equilibrium. I use detailed data on medical imaging visits to examine the introduction of a state-run website

providing information about out-of-pocket prices for a subset of procedures. Unlike other price transparency tools, the website could be used by all privately insured individuals in the state, potentially generating both demand- and supply-side effects. Exploiting variation across procedures available on the website as well as the timing of the introduction, estimates imply a 3 percent reduction in spending for visits with information available on the website. This is due in part to a shift to lower cost providers, especially for patients paying the highest proportion of costs. Furthermore, supply-side effects play a significant role—there are lower negotiated prices in the long-run, benefiting all insured individuals even if they do not use the website. Supply-side effects reduce price dispersion and are especially relevant when medical providers operate in concentrated markets. The supply-side effects of price transparency are important given that high prices are thought to be the primary cause of high private health care spending in the US.

I hope we learn more about this soon.

From the comments, on alcohol abuse

I refer you to Prevalence of 12-Month Alcohol Use, High-Risk Drinking, and DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013. My apologies for not being able to locate the primary data sooner.

Key summary quotes below:

Twelve-month alcohol use significantly increased from 65.4% in 2001-2002 to 72.7% in 2012-2013, a relative percentage increase of 11.2%

The prevalence of 12-month high-risk drinking increased significantly between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013 from 9.7% to 12.6% (change, 29.9%) in the total population.

The prevalence of 12-month DSM-IV AUD increased significantly from 8.5% to 12.7% (change, 49.4%) in the total population.

Twelve-month DSM-IV AUD among 12-month alcohol users significantly increased from 12.9% to 17.5% (change, 35.7%) in the total population.

At the end of the day, I am still going to trust outcomes data over survey data. People lie, autopsies don’t. What I know is that acute alcohol poisoning increased by 700% in 20 years. You die from acute alcohol poisoning not because you slowly got sick over years, but because you drank so much so quickly that your body is overwhelmed. And this is in spite of the medical profession getting better at hemodialysis to bring down acutely toxic ethanol poisoning.

What I also know is that alcohol related hepatic deaths bottomed out in 2003 and have since been rising rapidly (~50% increase). This is due to the fact that the generation socialized by prohibition had lower lifetime alcohol use and problematic alcohol use than the generations before or after. As that generation died off, or aged out, successive generations who drank more started refilling the hepatic wards. Even more fun for every age bracket, we are seeing more alcohol related hepatic death than we saw a decade ago for those same age brackets excepting only the youngest cohorts.

These are basically impossible to square with a thesis of no substantial change in drinking patterns. They fit quite nicely with formal epidemiological surveys showing more problematic drinking and a shift in alcohol consumption.

That is from “Sure,” see also his/her other comments in the longer thread.

Taipei bleg

I haven’t been in ages, so please tell me what to do. I will be there soon. I thank you all in advance for the usual wisdom and sage counsel.

Tuesday assorted links

1. James Hamilton on Libra. And Barry Eichengreen on Libra. And Ben Thompson on Libra.

2. African internet shutdowns are increasing.

4. I am not sure how I feel about this obituary of Norman Stone. And is “bizarrely” really the right word?

5. China’s favorite food delivery service is now worth more than its biggest internet search firm.

Are quality-adjusted medical prices declining for chronic disease?

At least for diabetes care, the answer seems to be yes, according to Karen Eggleson, et.al.:

We analyze individual-level panel data on medical spending and health outcomes for 123,548 patients with type 2 diabetes in four health systems. Using a “cost-of-living” method that measures value based on improved survival, we find a positive net value of diabetes care: the value of improved survival outweighs the added costs of care in each of the four health systems. This finding is robust to accounting for selective survival, end-of-life spending, and a range of values for a life-year or, equivalently, to attributing only a fraction of survival improvements to medical care.

That is from a new NBER working paper. One way to read this paper is to be especially optimistic about medical progress, and also the U.S. health care system and furthermore the net contribution of science and medicine to economic growth. Another way to read this paper is to be especially pessimistic about human discipline and the ability to follow doctor’s orders.

Tearing Up an Economics Textbook

Robert Samuelson, the economics columnist, has written a column titled, It’s time we tear up our economics textbooks and start over. What he actually says is we should tear up Greg Mankiw’s Principles of Economics:

But as a teaching device, [Mankiw’s] “Principles of Economics” has fallen behind. There’s little analysis of the impact of the Internet and digitalization on competition and markets. I couldn’t find either Apple or Facebook in the index; Google gets a few mentions.

Likewise, little attention is paid to the 2007-2009 Great Recession, the worst business downturn since the Great Depression, which also receives scant coverage relative to its significance. (Together, the two recessions receive about three pages, from 725 to 727.)

There’s some misleading information about the Great Recession and parallel financial crisis. On Page 691, we have this: “Today, bank runs are not a major problem for the U.S. banking system or the Fed.” This would surely surprise the Fed, which poured trillions of dollars into the economy to prevent financial collapse.

Mankiw’s assertion can be defended on narrow, technical grounds. There was no run by retail depositors (people like you and me) against commercial banks. We were protected by deposit insurance. But there was a huge run — a panic — by institutional investors (pension funds, hedge funds, insurance companies, endowments) that withdrew funds from traditional banks, investment banks and the commercial paper market.

…Mankiw’s textbook needs more than a touch-up; it needs a major overhaul. It has very little history: for example, the industrialization of the 19th century. Nor is there much about the expansion of the global economy. China gets a few mentions.

The market for principles textbooks, however, is competitive and there are alternatives to Mankiw. Krugman and Wells, for example, have a lot of very interesting boxes on the world economy and historical events. Modern Principles of Economics doesn’t use boxes but we illustrate the principles of economics with historical events and, of course, we use tech companies such as Facebook and Apple to discuss network effects and coordination games. Samuelson is a bit harsh on Mankiw, however, because it’s very easy to overwhelm students with details. Like physics, economics is powerful because it explains many things with a handful of principles. It’s true that Mankiw’s book doesn’t have much history or color–his paradigmatic market is the market for ice cream–but abstraction can focus attention. The tradeoff, of course, is that it can also lead to vanilla economics. But the Mankiw text is clearly written and the micro text is especially well organized, one reason we chose a similar organization for Modern Principles.

In Modern Principles we illustrate the ideas with more interesting markets but we work with them repeatedly so students don’t become overwhelmed. Our paradigmatic market is the market for oil. We use it to teach supply and demand, cartels, and the importance of real macroeconomic shocks. Using the market for oil also lets us teach about some important events in world history such as the OPEC oil crisis and the industrialization of China.

Samuelson is correct that the financial crisis was a run on the shadow banks but he’s incorrect that this isn’t taught to students of Econ 101. Here’s Tyler on the financial crisis. He covers leverage, securitization, asymmetric information, bank runs, fire sales and the rise of the shadow banking system. Students with the right textbook are well informed about the financial crisis and the economic principles that can help us to understand, analyze and perhaps avoid future financial crises.

Lobbying sentences to ponder

Specifically, corporations lobby more, and harder, as legislatures polarize, but they do so primarily in response to rising liberalism among Democrats.

Here is the full paper by William Massengill, via Matt Grossman.

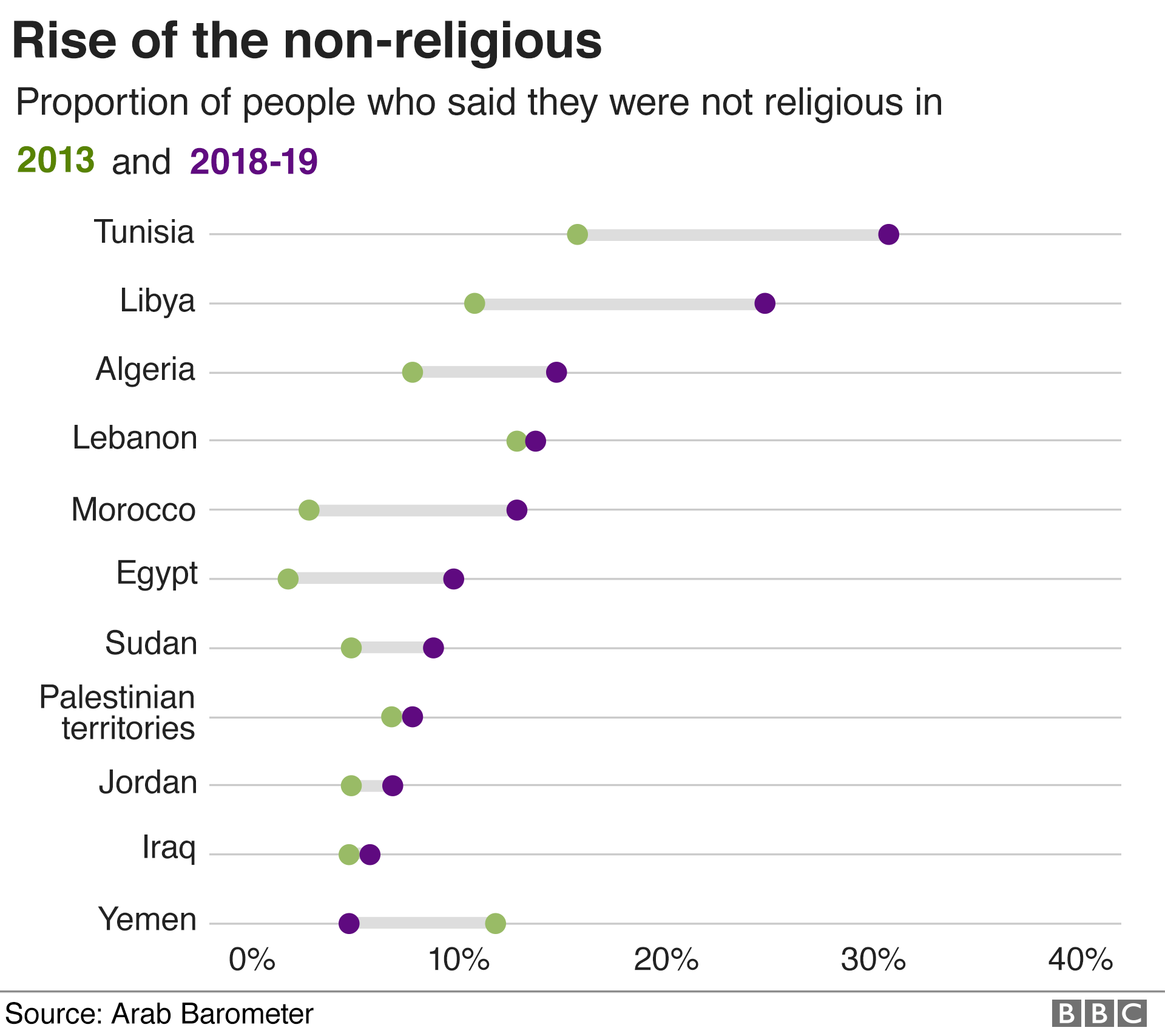

The rise of the non-religious in the Middle East and nearby

Here is the BBC source, which has several other interesting pieces of information, for instance in the polled countries Erdogan is more popular than Putin who in turn is more popular than Trump: 51-28-12% on the approval ratings.

Here is the BBC source, which has several other interesting pieces of information, for instance in the polled countries Erdogan is more popular than Putin who in turn is more popular than Trump: 51-28-12% on the approval ratings.

Those new (?) service sector jobs

Teen mail boat jumpers: “Rain or shine won’t keep these mail jumpers from their appointed rounds. Each year a bunch of high school seniors try out as mail jumpers on Wisconsin’s Lake Geneva and it may be the best summer job ever. The challenge is to dash to the mailbox and race back to the boat before it pulls away. The boat slows down but never stops so you have to…”

Via Jamie Jenkins.

Monday assorted links

1. The commercialization of cornhole.

2. Argentina interview (in Spanish).

3. China and North Korea (NYT).

4. Robert Kaplan on China and other stuff.

5. “This study uses an experimental design to explore how people react to criminal stigma in the context of online dating…White females disclosing parole matched at a higher rate than White females not disclosing parole.” Link here.

6. Is Amazon getting worse at bookselling? (NYT)

The Economist covers Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?

The Economist does a very nice job covering Why Are the Prices So D*mn High.

Baumol’s earliest work on the subject, written with William Bowen, was published in 1965. Analyses like that of Messrs Helland and Tabarrok nonetheless feel novel, because the implications of cost disease remain so underappreciated in policy circles. For instance, the steadily rising expense of education and health care is almost universally deplored as an economic scourge, despite being caused by something indubitably good: rapid, if unevenly spread, productivity growth. Higher prices, if driven by cost disease, need not mean reduced affordability, since they reflect greater productive capacity elsewhere in the economy. The authors use an analogy: as a person’s salary increases, the cost of doing things other than work—like gardening, for example—rises, since each hour off the job means more forgone income. But that does not mean that time spent gardening has become less affordable.

It’s an implication of the Baumol effect that everyone ends up working in a low productivity industry!

The only true solution to cost disease is an economy-wide productivity slowdown—and one may be in the offing. Technological progress pushes employment into the sectors most resistant to productivity growth. Eventually, nearly everyone may have jobs that are valued for their inefficiency: as concert musicians, or artisanal cheesemakers, or members of the household staff of the very rich. If there is no high-productivity sector to lure such workers away, then the problem does not arise.

Misunderstanding the Baumol effect can lead to a cure worse than the “disease”:

These possibilities reveal the real threat from Baumol’s disease: not that work will flow toward less-productive industries, which is inevitable, but that gains from rising productivity are unevenly shared. When firms in highly productive industries crave highly credentialed workers, it is the pay of similar workers elsewhere in the economy—of doctors, say—that rises in response. That worsens inequality, as low-income workers must still pay higher prices for essential services like health care. Even so, the productivity growth that drives cost disease could make everyone better off. But governments often do too little to tax the winners and compensate the losers. And politicians who do not understand the Baumol effect sometimes cap spending on education and health. Unsurprisingly, since they misunderstand the diagnosis, the treatment they prescribe makes the ailment worse.

My only complaint is that the excellent reviewer has not followed our lead and called it the Baumol effect–cost disease is a misleading name!

Addendum: Other posts in this series.