Month: April 2020

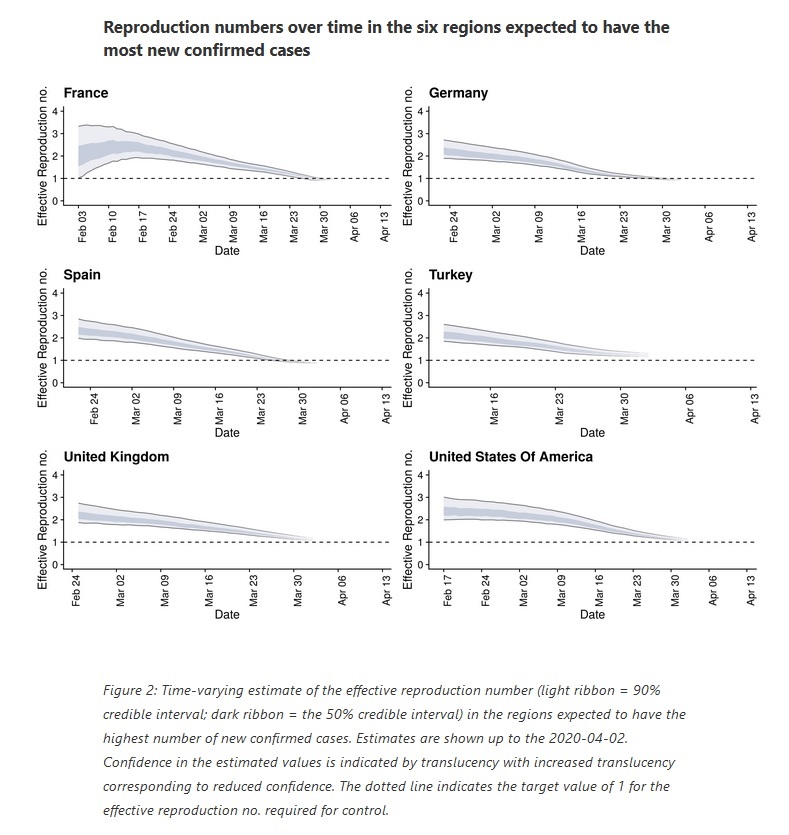

Suppression is Working, R is Declining

The reproduction factor is declining. We need to push it below 1 for the virus to start to fade away and then we can move to safety protocols and mass testing.

These estimates are from the Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. More details here.

Why social distancing will persist

Some 72% of Americans polled said they would not attend if sporting events resumed without a vaccine for the coronavirus. The poll, which had a fairly small sample size of 762 respondents, was released Thursday by Seton Hall University’s Stillman School of Business.

When polling respondents who identified as sports fans, 61% said they would not go to a game without a vaccine. The margin of error is plus-or-minus 3.6%.

Only 12% of all respondents said they would go to games if social distancing could be maintained, which would likely lead to a highly reduced number of fans, staff and media at games.

I doubt if that poll is extremely scientific, but the key fact here is that people go to NBA games, and most other public entertainments, in groups. Fast forward a bit and see how the group negotiations will go. Of a foursome, maybe three people would go to the game and one would not. That group is likely to end up doing something else altogether different, without 19,000 other cheering fans screaming and breathing into their faces.

If half the people say they will go, that does not mean you get half the people. It means you hardly get anybody.

By the way, what percentage of the American population will refuse or otherwise evade this vaccine, assuming we come up with one of course?

Here is the ESPN story link.

From my email, a note about epidemiology

This is all from my correspondent, I won’t do any further indentation and I have removed some identifying information, here goes:

“First, some background on who I am. After taking degrees in math and civil engineering at [very very good school], I studied infectious disease epidemiology at [another very, very good school] because I thought it would make for a fulfilling career. However, I became disillusioned with the enterprise for three reasons:

- Data is limited and often inaccurate in the critical forecasting window, leading to very large confidence bands for predictions

- Unless the disease has been seen before, the underlying dynamics may be sufficiently vague to make your predictions totally useless if you do not correctly specify the model structure

- Modeling is secondary to the governmental response (e.g., effective contact tracing) and individual action (e.g., social distancing, wearing masks)

Now I work as a quantitative analyst for [very, very good firm], and I don’t regret leaving epidemiology behind. Anyway, on to your questions…

What is an epidemiologist’s pay structure?

The vast majority of trained epidemiologists who would have the necessary knowledge to build models are employed in academia or the public sector; so their pay is generally average/below average for what you would expect in the private sector for the same quantitative skill set. So, aside from reputational enhancement/degradation, there’s not much of an incentive to produce accurate epidemic forecasts – at least not in monetary terms. Presumably there is better money to be made running clinical trials for drug companies.

On your question about hiring, I can’t say how meritocratic the labor market is for quantitative modelers. I can say though that there is no central lodestar, like Navier-Stokes in fluid dynamics, that guides the modeling framework. True, SIR, SEIR, and other compartmental models are widely used and accepted; however, the innovations attached to them can be numerous in a way that does not suggest parsimony.

How smart are epidemiologists?

The quantitative modelers are generally much smarter than the people performing contact tracing or qualitative epidemiology studies. However, if I’m being completely honest, their intelligence is probably lower than the average engineering professor – and certainly below that of mathematicians and statisticians.

My GRE scores were very good, and I found epidemiology to be a very interesting subject – plus, I can be pretty oblivious to what other people think. Yet when I told several of my professors in math and engineering of my plans, it was hard for me to miss their looks of disappointment. It’s just not a track that driven, intelligent people with a hint of quantitative ability take.

What is the political orientation of epidemiologists? What is their social welfare function?

Left, left, left. In the United States, I would be shocked if more than 2-5% of epidemiologists voted for Republicans in 2016 – at least among academics. At [aforementioned very very good school], I’d be surprised if the number was 1%. I remember the various unprompted bashing of Trump and generic Republicans on political matters unrelated to epidemiology in at least four classes during the 2016-17 academic year. Add that to the (literal) days of mourning after the election, it’s fair to say that academic epidemiologists are pretty solidly in the left-wing camp. (Note: I didn’t vote for Trump or any other Republican in 2016 or 2018)

I was pleasantly surprised during my time at [very, very good school] that there was at least some discussion of cost-benefit analysis for public health actions, including quarantine procedures. Realistically though, there’s a dominant strain of thought that the economic costs of an action are secondary to stopping the spread of an epidemic. To summarize the SWF: damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead!

Do epidemiologists perform uncertainty quantification?

They seem to play around with tools like the ensemble Kalman filter (found in weather forecasting) and stochastic differential equations, but it’s fair to say that mechanical engineers are much better at accounting for uncertainty (especially in parameters and boundary conditions) in their simulations than epidemiologists. By extension, that probably means that econometricians are better too.”

TC again: I am happy to pass along other well-thought out perspectives on this matter, and I would like to hear a more positive take. Please note I am not endorsing these (or subsequent) observations, I genuinely do not know, and I will repeat I do not think economists are likely better. It simply seems to me that “who are these epidemiologists anyway?” is a question now worth addressing, and hardly anyone is willing to do that.

As an opening gambit, I’d like to propose that we pay epidemiologists more. (And one of my correspondents points out they are too often paid on “soft money.”) I know, I know, this plays with your mood affiliation. You would like to find a way of endorsing that conclusion, without simultaneously admitting that right now maybe the quality isn’t quite high enough.

Epidemiology and selection problems and further heterogeneities

Richard Lowery emails me this:

I saw your post about epidemiologists today. I have a concern similar to point 4 about selection based what I have seen being used for policy in Austin. It looks to me like the models being used for projection calibrate R_0 off of the initial doubling rate of the outbreak in an area. But, if people who are most likely to spread to a large number of people are also more likely to get infected early in an outbreak, you end up with what looks kind of like a classic Heckman selection problem, right? In any observable group, there is going to be an unobserved distribution of contact frequency, and it would seem potentially first order to account for that.

As far as I can tell, if this criticism holds, the models are going to (1) be biased upward, predicting a far higher peak in the absence of policy intervention and (2) overstate the likely severity of an outcome without policy intervention, while potentially understating the value of aggressive containment measures. The epidemiology models I have seen look really pessimistic, and they seem like they can only justify any intervention by arguing that the health sector will be overwhelmed, which now appears unlikely in a lot of places. The Austin report did a trick of cutting off the time axis to hide that total infections do not seem to change that much under the different social distancing policies; everything just gets dragged out.

But, if the selection concern is right, the pessimism might be misplaced if the late epidemic R_0 is lower, potentially leading to a much lower effective spread rate and the possibility of killing the thing off at some point before it infects the number of people required to create the level of immunity the models are predicted require. This seems feasible based on South Korea and maybe China, at least for areas in the US that are not already out of control.

I do not know the answers to the questions raised here, but I do see the debate on Twitter becoming more partisan, more emotional, and less substantive. You cannot say that about this communication. From the MR comments this one — from Kronrad — struck me as significant:

One thing both economists and epidemiologists seem to be lacking is an awareness for the problems of aggregation. Most models in both fields see the population as one homogenous mass of individuals. But sometimes, individual variation makes a difference in the aggregate, even if the average is the same.

In the case of pandemics, it makes a big difference how that infection rate varies in the population. Most models assume that it is the same for everyone. But in reality, human interactions are not evenly distributed. Some people shake hands all day, while others spend their days mostly alone in front of a screen. This uneven distribution has an interesting effect: those who spread virus the most are also the most likely to get it. This means that the infection rate looks very higher in the beginning of a pandemic, but sinks once the super spreaders has the disease and got immunity. Also, it means herd immunity is reached much earlier: not after 70% of the population is immune, but after people who are involved in 70% of all human interactions are immune. At average, this is the same. But in practice, it can make a big difference.

I did a small simulation on this and came to the conclusion that with recursively applied Pareto-distribution where 1/3 of all people are responsible for 2/3 of all human interaction, herd immunity is already reached when 10% of the population had the virus. So individual variation in the infection rate can make an enormous difference that are be captured in aggregate models.

My quick and dirty simulation can be found here:

https://github.com/meisserecon/corona

See also Robin Hanson’s earlier post on variation in R0. C’mon people, stop your yapping on Twitter and write some decent blog posts on these issues. I know you can do it.

Sunday assorted links

1. Excellent thread, showing an actual understanding of public choice.

2. The mask as fashion statement.

3. Scott Sumner on the lower mortality estimates.

4. AMC movie theatres likely to go bankrupt soon.

6. The Belgium heterogeneity? And the Austrian heterogeneity?

Happy Easter

Credit: Saint Simeon Stylites the elder. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

What does this economist think of epidemiologists?

I have had fringe contact with more epidemiology than usual as of late, for obvious reasons, and I do understand this is only one corner of the discipline. I don’t mean this as a complaint dump, because most of economics suffers from similar problems, but here are a few limitations I see in the mainline epidemiological models put before us:

1. They do not sufficiently grasp that long-run elasticities of adjustment are more powerful than short-run elasticites. In the short run you socially distance, but in the long run you learn which methods of social distance protect you the most. Or you move from doing “half home delivery of food” to “full home delivery of food” once you get that extra credit card or learn the best sites. In this regard the epidemiological models end up being too pessimistic, and it seems that “the natural disaster economist complaints about the epidemiologists” (yes there is such a thing) are largely correct on this count. On this question economic models really do better, though not the models of everybody.

2. They do not sufficiently incorporate public choice considerations. An epidemic path, for instance, may be politically infeasible, which leads to adjustments along the way, and very often those adjustments are stupid policy moves from impatient politicians. This is not built into the models I am seeing, nor are such factors built into most economic macro models, even though there is a large independent branch of public choice research. It is hard to integrate. Still, it means that epidemiological models will be too optimistic, rather than too pessimistic as in #1. Epidemiologists might protest that it is not the purpose of their science or models to incorporate politics, but these factors are relevant for prediction, and if you try to wash your hands of them (no pun intended) you will be wrong a lot.

3. The Lucas critique, namely that agents within a model, knowing the model, will change how the model itself operates. Epidemiologists seem super-aware of this, much more than Keynesian macroeconomists are these days, though it seems to be more of a “I told you that you should listen to us” embodiment than trying to find an actual closed-loop solution for the model as a whole. That is really hard, either in macroeconomics or epidemiology. Still, on the predictive front without a good instantiation of the Lucas critique again a lot will go askew, as indeed it does in economics.

The epidemiological models also do not seem to incorporate Sam Peltzman-like risk offset effects. If you tell everyone to wear a mask, great! But people will feel safer as a result, and end up going out more. Some of the initial safety gains are given back through the subsequent behavioral adjustment. Epidemiologists might claim these factors already are incorporated in the variables they are measuring, but they are not constant across all possible methods of safety improvement. Ideally you may wish to make people safer in a not entirely transparent manner, so that they do not respond with greater recklessness. I have not yet seen a Straussian dimension in the models, though you might argue many epidemiologists are “naive Straussian” in their public rhetoric, saying what is good for us rather than telling the whole truth. The Straussian economists are slightly subtler.

4. Selection bias from the failures coming first. The early models were calibrated from Wuhan data, because what else could they do? Then came northern Italy, which was also a mess. It is the messes which are visible first, at least on average. So some of the models may have been too pessimistic at first. These days we have Germany, Australia, and a bunch of southern states that haven’t quite “blown up” as quickly as they should have. If the early models had access to all of that data, presumably they would be more predictive of the entire situation today. But it is no accident that the failures will be more visible early on.

And note that right now some of the very worst countries (Mexico, Brazil, possibly India?) are not far enough along on the data side to yield useful inputs into the models. So currently those models might be picking up too many semi-positive data points and not enough from the “train wrecks,” and thus they are too optimistic.

On this list, I think my #1 comes closest to being an actual criticism, the other points are more like observations about doing science in a messy, imperfect world. In any case, when epidemiological models are brandished, keep these limitations in mind. But the more important point may be for when critics of epidemiological models raise the limitations of those models. Very often the cited criticisms are chosen selectively, to support some particular agenda, when in fact the biases in the epidemiological models could run in either an optimistic or pessimistic direction.

Which is how it should be.

Now, to close, I have a few rude questions that nobody else seems willing to ask, and I genuinely do not know the answers to these:

a. As a class of scientists, how much are epidemiologists paid? Is good or bad news better for their salaries?

b. How smart are they? What are their average GRE scores?

c. Are they hired into thick, liquid academic and institutional markets? And how meritocratic are those markets?

d. What is their overall track record on predictions, whether before or during this crisis?

e. On average, what is the political orientation of epidemiologists? And compared to other academics? Which social welfare function do they use when they make non-trivial recommendations?

f. We know, from economics, that if you are a French economist, being a Frenchman predicts your political views better than does being an economist (there is an old MR post on this somewhere). Is there a comparable phenomenon in epidemiology?

g. How well do they understand how to model uncertainty of forecasts, relative to say what a top econometrician would know?

h. Are there “zombie epidemiologists” in the manner that Paul Krugman charges there are “zombie economists”? If so, what do you have to do to earn that designation? And are the zombies sometimes right, or right on some issues? How meta-rational are those who allege zombie-ism?

i. How many of them have studied Philip Tetlock’s work on forecasting?

Just to be clear, as MR readers will know, I have not been criticizing the mainstream epidemiological recommendations of lockdowns. But still those seem to be questions worth asking.

Saturday assorted links

1. MIE: “This Man Owns The World’s Most Advanced Private Air Force After Buying 46 F/A-18 Hornets.”

2. Romer tweet storm states his plan.

4. Is American innovation speeding up? (WSJ)

6. Non-exemplary lives (ouch). And what do the humanities do in a crisis?

7. Instagram strippers (NYT). And Bret Stephens: our regulatory state is failing us (NYT).

8. “Believe women,” selectively.

9. BloombergQuint on Alex and Shruti.

10. A proposal for releasing British young people (ever listen to early Clash?).

11. Arnold Kling annotates (and likes) my Princeton talk.

12. A Swede explains Sweden to an Israeli: “Some maintain that the Swedish policy can succeed only in Sweden, because of its distinctive characteristics – a country where population density is low, where a high percentage of the citizenry live in one-person households and very few households include people over 70 cohabiting with young people and children. Those are mitigating circumstances which the Swedes hope will work to their advantage.”

What should I ask Adam Tooze?

I will be doing a Conversation with him, no associated public event. He has been tweeting about the risks of a financial crisis during Covid-19, but more generally he is one of the most influential historians, currently being a Professor at Columbia University. His previous books cover German economic history, German statistical history, the financial crisis of 2008, and most generally early to mid-20th century European history. Here is his home page, here is his bio, here is his Wikipedia page.

So what should I ask him?

Discovering Safety Protocols

Walmart, Amazon and other firms are developing safety protocols for the COVID workplace. Walmart, for example, will be doing temperature checks of its employees:

Walmart Blog: As the COVID-19 situation has evolved, we’ve decided to begin taking the temperatures of our associates as they report to work in stores, clubs and facilities, as well as asking them some basic health screening questions. We are in the process of sending infrared thermometers to all locations, which could take up to three weeks.

Any associate with a temperature of 100.0 degrees will be paid for reporting to work and asked to return home and seek medical treatment if necessary. The associate will not be able to return to work until they are fever-free for at least three days.

Many associates have already been taking their own temperatures at home, and we’re asking them to continue that practice as we start doing it on-site. And we’ll continue to ask associates to look out for other symptoms of the virus (coughing, feeling achy, difficulty breathing) and never come to work when they don’t feel well.

Our COVID-19 emergency leave policy allows associates to stay home if they have any COVID-19 related symptoms, concerns, illness or are quarantined – knowing that their jobs will be protected.

Amazon is even investing in their own testing labs.

Amazon Blog: A next step might be regular testing of all employees, including those showing no symptoms. Regular testing on a global scale across all industries would both help keep people safe and help get the economy back up and running. But, for this to work, we as a society would need vastly more testing capacity than is currently available. Unfortunately, today we live in a world of scarcity where COVID-19 testing is heavily rationed.

If every person, including people with no symptoms, could be tested regularly, it would make a huge difference in how we are all fighting this virus. Those who test positive could be quarantined and cared for, and everyone who tests negative could re-enter the economy with confidence.

Until we have an effective vaccine available in billions of doses, high-volume testing capacity would be of great help, but getting that done will take collective action by NGOs, companies, and governments.

For our part, we’ve begun the work of building incremental testing capacity. A team of Amazonians with a variety of skills – from research scientists and program managers to procurement specialists and software engineers – have moved from their normal day jobs onto a dedicated team to work on this initiative. We have begun assembling the equipment we need to build our first lab (photos below) and hope to start testing small numbers of our front line employees soon.

Actions and experiments like these will discover ways to work safely till we reach the vaccine era.

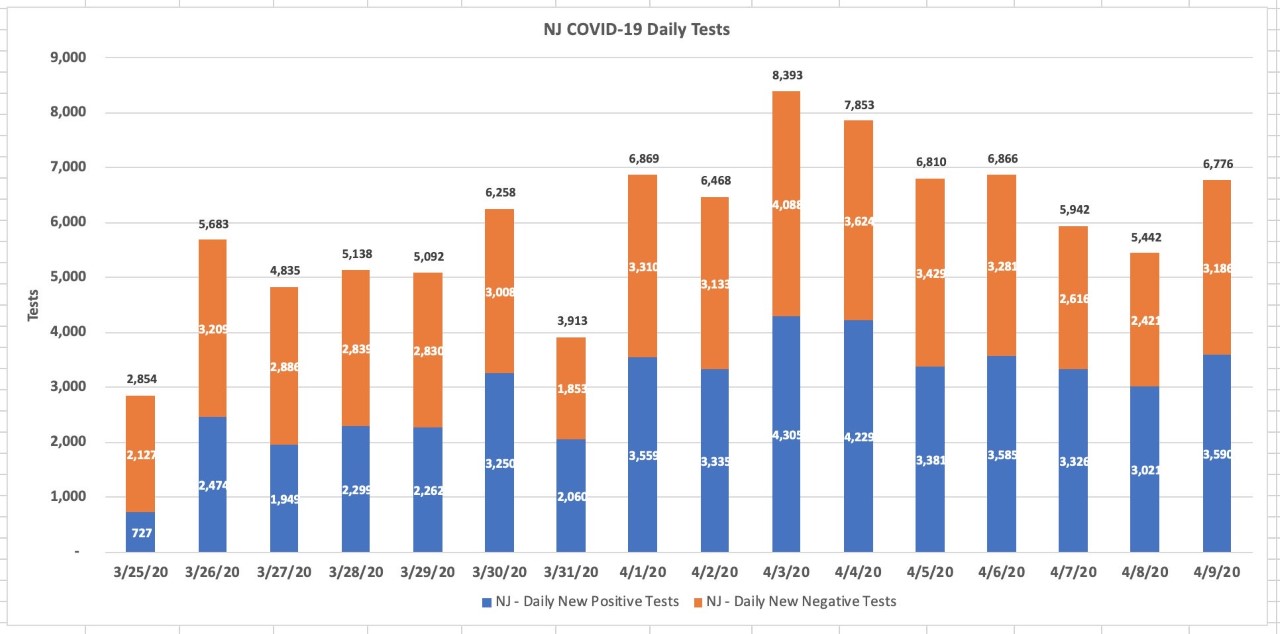

Covid-19 testing in New Jersey

Hey people, what is up with this?

Via John V. And in the meantime, the virus has now affected 70% of New Jersey’s long-term care centers.

My Princeton Covid-19 talk onYouTube, with slides

Here is the link, it is about one hour long, with questions interspersed throughout, the title is “The future social and political implications of COVID-19.” Self-recommending!

Why has the Census become less productive over time?

For the 1970 and subsequent censuses, the Postal Service took on an even greater role. Most households received a machine-readable survey by mail and returned it the same way. This cut out two labor- intensive processes: canvassing most households and transcribing data by hand. Censuses since 1970 have generally followed the same process. The biggest change was that the 2010 survey dropped the “long-form” census – a major labor-saving change that nevertheless did not have an obvious impact on the amount of labor expended.

Despite the introduction of labor-saving technologies, the Census hires more people relative to the population than it did in earlier periods. In 1950, 46 million households – the entire country – were canvassed by 170,000 field staff. In 2000, 45 million addressees failed to mail back the survey, and the Census Bureau hired 539,000 field staff to take on the task of nonresponse follow-up. What seems like basically the same task took three times as many employees.

That is from Salim Furth, there is much more at the link, including footnotes for the above excerpt. Of course this year the labor investment is likely to be much, much lower.

China estimate of the day

“The SpaceKnow data suggest a continued slowing in China’s economy, despite official data saying otherwise,” says Jeremy Fand, SpaceKnow’s chief executive.

Pollution data from SpaceKnow, collected via satellite by measuring things like methane and ozone over China, also suggest that activity remains depressed compared with previrus levels. That index, last updated on March 30, is unchanged from the end of February…

Regardless of why China’s activity remains lower than officially reported—whether it’s the virus, frozen demand, or a combination of factors—the point is that the country hasn’t yet begun to rebound.

Here is the full story by Lisa Beilfuss. Given this data, as I have been arguing, we should not expect a V-shaped U.S. recovery.

Apple and Google combine to help solve problems

Since COVID-19 can be transmitted through close proximity to affected individuals, public health organizations have identified contact tracing as a valuable tool to help contain its spread. A number of leading public health authorities, universities, and NGOs around the world have been doing important work to develop opt-in contact tracing technology. To further this cause, Apple and Google will be launching a comprehensive solution that includes application programming interfaces (APIs) and operating system-level technology to assist in enabling contact tracing. Given the urgent need, the plan is to implement this solution in two steps while maintaining strong protections around user privacy.

First, in May, both companies will release APIs that enable interoperability between Android and iOS devices using apps from public health authorities. These official apps will be available for users to download via their respective app stores.

Second, in the coming months, Apple and Google will work to enable a broader Bluetooth-based contact tracing platform by building this functionality into the underlying platforms. This is a more robust solution than an API and would allow more individuals to participate, if they choose to opt in, as well as enable interaction with a broader ecosystem of apps and government health authorities. Privacy, transparency, and consent are of utmost importance in this effort, and we look forward to building this functionality in consultation with interested stakeholders. We will openly publish information about our work for others to analyze.

Here is the full story. I cannot help but wonder if this would have happened sooner if not for a) antitrust concerns, and b) fears of existential risk due to attacks on the privacy issue. But I am pleased to see it is proceeding, and one hopes the risks on the legal side will not turn out to be too high.