Month: August 2020

U.S.A. facts of the day

One in four young adults between the ages of 18 and 24 say they’ve considered suicide in the past month because of the pandemic, according to new CDC data that paints a bleak picture of the nation’s mental health during the crisis.

The data also flags a surge of anxiety and substance abuse, with more than 40 percent of those surveyed saying they experienced a mental or behavioral health condition connected to the Covid-19 emergency. The CDC study analyzed 5,412 survey respondents between June 24 and 30.

The toll is falling heaviest on young adults, caregivers, essential workers and minorities. While 10.7 percent of respondents overall reported considering suicide in the previous 30 days, 25.5 percent of those between 18 to 24 reported doing so. Almost 31 percent of self-reported unpaid caregivers and 22 percent of essential workers also said they harbored such thoughts. Hispanic and Black respondents similarly were well above the average.

Here is the full story, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Friday assorted links

2. Deaton interviews Sen, with Tim Besley moderating, full of interesting content.

3. 80,000 hours Shruti Rajagopalan interviewed by Howie Lempel podcast, “What India did to stop Covid-19 and how well it worked,” self-recommending.

4. The British economy in pandemic (NYT).

5. Herbert Blomstedt back to conducting at age 93, an example for us all.

Young “stars” in economics

I had not seen this paper before, by Kevin A. Bryan, here is the abstract:

We construct a data set of job flyouts for junior economists between 2013 and 2018 to investigate three aspects of the market for “stars.” First, what is the background of students who become stars? Second, what type of research does the top of the market demand? Third, where do these students take jobs? Among other results, we show that stars are more likely to be international and male than PhDs overall, that theoretical and semi-theoretical approaches remain dominant, that American programs both produce the most stars and hire even more, that almost none are hired by the private sector, and that there is a strong shift toward having pre-PhD full-time academic research jobs.

Is this good news or bad? The paper is interesting throughout, here is another bit:

…both Americans and women are nearly twice as likely to have Applied Micro as a primary field compared to non-Americans and men.

As for country of origin of these star students, see p.5, I was surprised to see Germany rank second after the United States, with Italy and France not far behind, China coming next, then Argentina (!).

Via Soumaya Keynes.

The future of higher education could be India

This is a fantasy, not a prediction, still we can hold out hope, here is my latest Bloomberg column:

In my fantasy, the [Western] schools that are open to expanding their India operations will rise considerably in reputation. India, and South Asia more generally, is in the midst of a phenomenal explosion of talent in diverse fields…

You might wonder whether India actually needs all of these foreign branches, when it has some superb schools of its own, for instance the various Indian Institutes of Technology. In my fantasy, some Indian institutions of higher education will improve and force some competitors — shall we say UC Berkeley? — to leave the country. Yet many talented Indians will find attending a branch of Harvard or Yale to be an appealing option. Furthermore, the top foreign schools may form alliances with Indian institutions (as Yale has done in Singapore), giving students the best of both worlds.

This future gets better yet. Over time, the population of Indian alumni of prestigious U.S. universities will increase, relative to those who studied and graduated in America. America’s top schools thus will become engines of opportunity. It might also become obvious that the students attending in the U.S. are underperforming their Indian counterparts. What better way to light a competitive fire under the current dominant institutions?

And maybe some of the keenest and most ambitious American students will prefer to study in India rather than in America. (Perhaps a “canceled” American student could be sent to Brown Uttar Pradesh?) Wouldn’t you want to study with the very best of your peers, knowing you might be sitting next to the next generation’s Einstein, von Neumann or, of course Ramanujan?

There is more at the link, noting that this is a Swiftian fantasy of sorts.

What should I ask Edwidge Danticat?

I will be doing a Conversation with her, she is the famed Haitian author. Here is her extensive Wikipedia page. Or here is part of a shorter bio:

Author Edwidge Danticat was born on January 19, 1969 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti to André Danticat and Rose Danticat. In 1981, she moved to Brooklyn, New York, where she graduated from Clara Barton High School and received her B.A. degree in French literature from Barnard College in New York City in 1990; and her M.F.A. degree in creative writing from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island in 1993.

In 1983, at age fourteen, Danticat published her first writing in English, “A Haitian-American Christmas,” in New Youth Connections, a citywide magazine written by teenagers. Her next publication, “A New World Full of Strangers,” was about her immigration experience and led to the writing of her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory in 1994. In 1997, she was named one of the country’s best young authors by the literary journal Granta. Danticat’s other works include, Everything Inside, Claire of the Sea Light, Brother, I’m Dying, Krik? Krik!, The Farming of Bones, The Dew Breaker, and Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work.

Danticat has also taught creative writing at New York University and the University of Miami. She has worked with filmmakers Patricia Benoit and Jonathan Demme, on projects on Haitian art and documentaries about Haiti.

So what should I ask her?

Thursday assorted links

From the comments, comedy vs. drama

The Supply and Demand Model Predicts Behavior in Thousands of Experiments

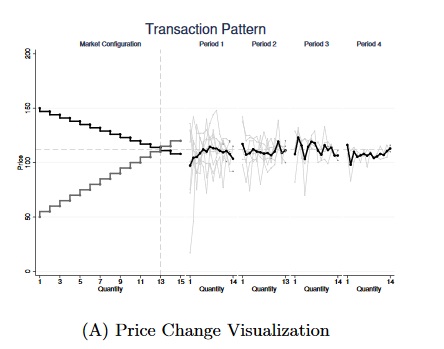

It is sometimes said that economics does not predict. In fact, Lin et al. (2020) (SSRN) (including Colin Camerer) find that the classic supply and demand model predicts behavior and outcomes in the double oral auction experiment in thousands of different experiments across the world. The model predicts average prices, final prices, who buys, who sells, and the distribution of gains very well as Vernon Smith first showed in the 1960s.

It is sometimes said that economics does not predict. In fact, Lin et al. (2020) (SSRN) (including Colin Camerer) find that the classic supply and demand model predicts behavior and outcomes in the double oral auction experiment in thousands of different experiments across the world. The model predicts average prices, final prices, who buys, who sells, and the distribution of gains very well as Vernon Smith first showed in the 1960s.

Indeed, the results from simple competitive buyer-seller trading appear to be as close to a culturally universal, highly reproducible outcome as one is likely to get in social science about collective behavior. This bold claim is limited, of course, by the fact that all these data are high school and college students in classes in “WEIRD” societies (Henrich et al.,2010b). Given this apparent robustness, it would next be useful to establish if emergence of CE in small buyer-seller markets extends to small-scale societies, across the human life cycle, to adult psychopathology and cognitive deficit, and even to other species.

It is true that economic theory is less capable of explaining the process by which prices and quantities reach equilibrium levels. Adam Smith’s theory about how competitive equilibrium is reached (“as if by an invisible hand”) has been improved upon only modestly. The authors, however, are able to test several theories of market processes and find that zero-intelligence theories tend to do better, though not uniformly so, than theories requiring more strategic and forward thinking behavior by market participants. The double-oral auction is powerful because the market is intelligent even when the traders are not.

The authors also find that bargaining behavior in the ultimatum game is reproducible in thousands of experiments. Simple economic theory makes very poor predictions (offer and accept epsilon) in this model but the deviations are well known and reproducible around the world (participants, for example, are more likely to accept and to accept quickly a 50% split than a split at any other level).

The experiments were run using MobLab, the classroom app, and were run without monetary incentives.

Tyler and I use Vernon Smith’s experiments to explain the Supply-Demand model in our textbook, Modern Principles, and it’s always fun to run the same experiment in the classroom. I’ve done this many times and never failed to reach equilibrium!

What is good news and bad news on the Covid-19 front

Following on my earlier analysis, ideally you want that super-spreaders are a fixed group who do not rotate much. That makes semi-effective herd immunity easier to reach in a region. So, in Bayesian terms, for a given super-spreader event, exactly which kind of story should you be rooting for?

Let’s say (hypothetically) that being a super-spreader has to do with your innate propensity to be infectious, as might be determined say by your genetic make-up. Then it is easier for the super-spreaders to acquire at least partial immunity, without a new group of super-spreaders rising up to take their place.

Alternatively, let’s say that being a super-spreader has to do with being in some relatively well-defined occupations and situations, such as singing in a church choir. That is a less optimistic prognosis, but still one of the better scenarios, as in principle it is possible to shut down many of those opportunities and thus block out the potential super-spreaders from doing their thing.

You should feel less good when you read of super-spreading events in very general public spaces, such as elevators, movie theaters, and office buildings. Those events, in Bayesian fashion, boost the probability that super-spreading is a generic ability, attached to a wide variety of fairly general situations. That raises the chance that, even after some super-spreaders acquire partial immunity, other super-spreaders will step in and play similar roles. Quite possibly all sorts of individuals — and not just those genetically endowed with super-powerful sneezes — are capable of super-spreading in small, enclosed public spaces.

You really do want those super-spreaders to be inelastic in supply.

Probabilistic profit from UFOs?

Let’s say the rest of the market was undervaluing the chance of UFOs being “something interesting.” What might be the proper trade? David S. emails me, and I will dispense with further indentation but what follows are his words not mine:

“Some potential food for thought:

– Going long volatility or long defense stocks seems like the most conventional answer.

– An even more conventional answer would be that it wouldn’t matter since any apocalypse means that even a correct bet is unlikely to have material redeemable value.

– Rather than framing the payout event as the binary of an actual UFO invasion, an alternative framing would be to bet on further government leaks causing the market to move it’s probability of invasion / apocalypse from 0.00% to 0.01%.

- Should you at least shorten the duration of your holdings on the margin? With interest rates near zero and record(-ish) high PE multiples, shouldn’t you be (marginally) less willing to pay for far-out cash flows? Could this finally fuel a resurgence of the value factor vs the growth factor?

- To take it a step further, should people consume more today and invest less given that the EV/NPV of these payouts will be somewhat lower?

- Other than high-dividend stocks and cash, what other trades are short-duration without going to zero if the apocalypse fails to arrive on time?

– My contrarian approach would be to go very long due to the underrated potential of technology transfer and overrated potential of apocalypse (especially in the near-term). For instance, if we found intelligent life on a planet like Mars (but less intelligent than humans), it would likely be decades between first contact and when humans would muster a military force to extinguish or fully dominate the other species (if ever). Also, based on the continued existence of thousands of species (many of which are flourishing) on earth in parallel with human existence, its not clear why we would assume that a more intelligent form of life that engages with humans would even try to extinguish. Per Steven Pinker, more intelligent species would likely also be more moral and therefore less likely to be focused on zero-sum extinction.”

TC again: Obviously many short positions would be in order. In terms of longs, my intuitions would be to buy a very diverse bundle of natural resources. Presumably the aliens have not brought many minerals with them, and they will need some minerals to do…whatever it is they plan on doing. Maybe lots of minerals. But you don’t know which ones.

Wednesday assorted links

1. “On November 9th, 2019 the Center for Genomic Gastronomy will install the Smog Tasting project in Hong Kong City Hall. Citizens will be able to taste and compare a range of smog meringues collected from around the city considering the flavors, ingredients, and composition of Hong Kong’s atmospheric taste of place.” Link here.

2. An example of objectionable “medical ethics” from blue-check Twitter: “The Russian vaccine gamble is reckless and foolish, whether ‘it works’ or not. Actually, the worst long-term outcome may be for the gamble to pay off, at the cost of decades of health care ethics ruined…” I mean that might be true, but without argument or further calculation? Really? You can read the longer treatment here.

3. The llama cure for Covid-19?

4. Coasean bargaining over ransomware.

5. On-line version of a Donald J. Harris book on income distribution.

My Conversation with Nicholas Bloom

Excellent and interesting throughout, here is the transcript, video, and audio. Here is part of the summary:

He joined Tyler for a conversation about which areas of science are making progress, the factors that have made research more expensive, why government should invest more in R&D, how lean management transformed manufacturing, how India’s congested legal system inhibits economic development, the effects of technology on Scottish football hooliganism, why firms thrive in China, how weak legal systems incentivize nepotism, why he’s not worried about the effects of remote work on American productivity (in the short-term), the drawbacks of elite graduate programs, how his first “academic love” shapes his work today, the benefits of working with co-authors, why he prefers periodicals and podcasts to reading books, and more.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: If I understand your estimates correctly, efficacy per researcher, as you measure it, is falling by about 5 percent a year [paper here]. That seems phenomenally high. What’s the mechanism that could account for such a rapid decline?

BLOOM: The big picture — just to make sure everyone’s on the same page — is, if you look in the US, productivity growth . . . In fact, I could go back a lot further. It’s interesting — you go much further, and you think of European and North American history. In the UK that has better data, there was very, very little productivity growth until the Industrial Revolution. Literally, from the time the Romans left in whatever, roughly 100 AD, until 1750, technological progress was very slow.

Sure, the British were more advanced at that point, but not dramatically. The estimates were like 0.1 percent a year, so very low. Then the Industrial Revolution starts, and it starts to speed up and speed up and speed up. And technological progress, in terms of productivity growth, peaks in the 1950s at something like 3 to 4 percent a year, and then it’s been falling ever since.

Then you ask that rate of fall — it’s 5 percent, roughly. It would have fallen if we held inputs constant. The one thing that’s been offsetting that fall in the rate of progress is we’ve put more and more resources into it. Again, if you think of the US, the number of research universities has exploded, the number of firms having research labs.

Thomas Edison, for example, was the first lab about 100 years ago, but post–World War II, most large American companies have been pushing huge amounts of cash into R&D. But despite all of that increase in inputs, actually, productivity growth has been slowing over the last 50 years. That’s the sense in which it’s harder and harder to find new ideas. We’re putting more inputs into labs, but actually productivity growth is falling.

COWEN: Let’s say paperwork for researchers is increasing, bureaucratization is increasing. How do we get that to be negative 5 percent a year as an effect? Is it that we’re throwing kryptonite at our top people? Your productivity is not declining 5 percent a year, or is it? COVID aside.

BLOOM: COVID aside. Yeah, it’s hard to tell your own productivity. Oddly enough, I always feel like, “Ah, you know, the stuff that I did before was better research ideas.” And then something comes along. I’d say personally, it’s very stochastic. I find it very hard to predict it. Increasingly, it comes from working with basically great, and often younger, coauthors.

Why is it happening at the aggregate level? I think there are three reasons going on. One is actually come back to Ben Jones, who had an important paper, which is called, I believe, “[Death of the] Renaissance Man.” This came out 15 years ago or something. The idea was, it takes longer and longer for us to train.

Just in economics — when I first started in economics, it was standard to do a four-year PhD. It’s now a six-year PhD, plus many of the PhD students have done a pre-doc, so they’ve done an extra two years. We’re taking three or four years longer just to get to the research frontier. There’s so much more knowledge before us, it just takes longer to train up. That’s one story.

A second story I’ve heard is, research is getting more complicated. I remember I sat down with a former CEO of SRI, Stanford Research Institute, which is a big research lab out here that’s done many things. For example, Siri came out of SRI. He said, “Increasingly it’s interdisciplinary teams now.”

It used to be you’d have one or two scientists could come up with great ideas. Now, you’re having to combine a couple. I can’t remember if he said for Siri, but he said there are three or four different research groups in SRI that were being pulled together to do that. That of course makes it more expensive. And when you think of biogenetics, combining biology and genetics, or bioengineering, there’s many more cross-field areas.

Then finally, as you say, I suspect regulation costs, various other factors are making it harder to undertake research. A lot of that’s probably good. I’d have to look at individual regulations. Health and safety, for example, is probably a good idea, but in the same way, that is almost certainly making it more expensive to run labs…

COWEN: What if I argued none of those are the central factors because, if those were true as the central factors, you would expect the wages of scientists, especially in the private sector, to be declining, say by 5 percent a year. But they’re not declining. They’re mostly going up.

Doesn’t the explanation have to be that scientific efforts used to be devoted to public goods much more, and now they’re being devoted to private goods? That’s the only explanation that’s consistent with rising wages for science but a declining social output from her research, her scientific productivity.

And this:

COWEN: What exactly is the value of management consultants? Because to many outsiders, it appears absurd that these not-so-well-trained young people come in. They tell companies what to do. Sometimes it’s even called fraudulent if they command high returns. How does this work? What’s the value added?

Definitely recommended

*An American Pickle*

I am not giving away anything by telling you the basic premise of this film is that a Yiddish-speaking NYC Ellis Island arrival is time-traveled 100 years into the future to the current day, where he meets up with his great-grandson, and the two start hanging out together.

At first it seems silly and slight, but over a short 90 minutes it is revealed to be one of the best movies about entrepreneurship ever made, a biting critique of PC and Millennials, a look at current American “complacency”/decadence, and a paean to the value of family and religion and Judaism in particular, all within the framework of a sufficiently entertaining comedy. It is one of the most successful “right-wing movies” I have seen.

Not surprisingly, the reviews about this one are clueless, but large numbers of MR readers will pick up on the numerous subtle points and jabs.

Here is Wikipedia on the movie. Streaming on HBO/HBO Max, but of course see it on a big screen if you can.

Why herd immunity is worth less than you might think

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column. The evidence in favor of at least partial herd immunity continues to pile up, but still don’t get too cheery. One worry is that herd immunity might prove only temporary:

First, many herd immunity hypotheses invoke the idea of “superspreaders” — that a relatively small number of people account for a disproportionate amount of the contagion. Perhaps it is the bartenders, church choir singers and bus drivers who spread the virus to so many others early on in the pandemic. Now that those groups have been exposed to a high degree and have acquired immunity, it might be much harder to distribute the virus.

That logic makes some sense except for one issue: namely, that the identities of potential superspreaders can change over time. For instance, perhaps choir singers were superspreaders earlier in the winter, but with most choral singing shut down, maybe TSA security guards are the new superspreaders. After all, air travel has been rising steadily. Or the onset of winter and colder weather might make waiters a new set of superspreaders, as more people dine inside.

In other words, herd immunity might be a temporary state of affairs. The very economic and social changes brought by the virus may induce a rotation of potential superspreaders, thereby undoing some of the acquired protection.

In other words, the fight never quite ends. Here is another and possibly larger worry:

Another problem is global in nature and could prove very severe indeed. One possible motivation for the herd immunity hypothesis is that a significant chunk of the population already had been exposed to related coronaviruses, thereby giving it partial immunity to Covid-19. In essence, that “reservoir” of protected individuals has helped to slow or stop the spread of the virus sooner than might have been expected.

There is a catch, however. If true, that hypothesis means that the virus spreads all the more rapidly among groups with little or no protection. (Technically, if R = 2.5, but say 50% of the core population has protection, there is an R of something like 5 for the unprotected population, to get the aggregate R to 2.5.) So if some parts of the world enjoy less protection from cross-immunities, Covid-19 is likely to ravage them all the more — and very rapidly at that.

Again, this is all in the realm of the hypothetical. But that scenario might help explain the severe Covid-19 toll in much of Latin America, and possibly in India and South Africa. Herd immunity, as a general concept, could mean a more dangerous virus for some areas and population subgroups.

There are further arguments at the link.

The classical theory of economic growth, by Donald J. Harris

By Donald J. Harris, here is the abstract:

Focused on the emerging conditions of industrial capitalism in Britain in their own time, the classical economists were able to provide an account of the broad forces that influence economic growth and of the mechanisms underlying the growth process. Accumulation and productive investment of a part of the social surplus in the form of profits were seen as the main driving force. Hence, changes in the rate of profit were a decisive reference point for analysis of the long-term evolution of the economy. As worked out most coherently by Ricardo, the analysis indicated that in a closed economy there is an inevitable tendency for the rate of profit to fall. In this article, the essential features of the classical analysis of the accumulation process are presented and formalized in terms of a simple model.

Here is the full piece. Here are other pieces by Donald J. Harris, professor emeritus at Stanford, economist, and father of Kamala Harris. Here is further background on him.

That is a remark by WB on An American Pickle. One striking feature of the creativity of Shakespeare, of course, is that he does not follow this usual pattern.