Month: November 2021

Mobile internet and political polarization

So far this paper is my favorite of the job market papers I have seen this year, and it is by Nikita Melnikov of Princeton. Please do read each and every sentence of the abstract carefully, as each and every sentence offers interesting and substantive content:

How has mobile internet affected political polarization in the United States? Using Gallup Daily Poll data covering 1,765,114 individuals in 31,499 ZIP codes between 2008 and 2017, I show that, after gaining access to 3G internet, Democratic voters became more liberal in their political views and increased their support for Democratic congressional candidates and policy priorities, while Republican voters shifted in the opposite direction. This increase in polarization largely did not take place among social media users. Instead, following the arrival of 3G, active internet and social media users from both parties became more pro-Democratic, whereas

less-active users became more pro-Republican. This divergence is partly driven by differences in news consumption between the two groups: after the arrival of 3G, active internet users decreased their consumption of Fox News, increased their consumption of CNN, and increased their political knowledge. Polarization also increased due to a political realignment of voters: wealthy, well-educated people became more liberal; poor, uneducated people—more conservative.

My read of these results (not the author’s to be clear!) is that the mobile internet polarized the Left, but not so much the Right. What polarized the Right was…the polarization of the Left, and not the mobile internet.

And please do note this sentence: “This increase in polarization largely did not take place among social media users.” It seems that on-line versions of older school media did a lot of the work.

Here are further papers by Melnikov.

The economics of medical procedure innovation

Important NBER work from David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, Christopher Heard, and Bingxiao Wu on an understudied intervention:

This paper explores the economic incentives for medical procedure innovation. Using a proprietary dataset on billing code applications for emerging medical procedures, we highlight two mechanisms that could hinder innovation. First, the administrative hurdle of securing permanent, reimbursable billing codes substantially delays innovation diffusion. We find that Medicare utilization of innovative procedures increases nearly nine-fold after the billing codes are promoted to permanent (reimbursable) from provisional (non-reimbursable). However, only 29 percent of the provisional codes are promoted within the five-year probation period. Second, medical procedures lack intellectual property rights, especially those without patented devices. When appropriability is limited, specialty medical societies lead the applications for billing codes. We indicate that the ad hoc process for securing billing codes for procedure innovations creates uncertainty about both the development process and the allocation and enforceability of property rights. This stands in stark contrast to the more deliberate regulatory oversight for pharmaceutical innovations.

Here are ungated copies.

Saturday assorted links

Infrastructure week?

It seems the new NYC train tunnel will be built. And WSJ on what is in the bill. And an AP summary. And lots of discretionary money for the DOT. And at least in the nominal vote count Republicans saved the bill?

Cognitive sentences to ponder

The main conclusions are that, although children’s intelligence relative to their peers remains associated with social class, the association may have weakened recently, mainly because the average intelligence in the highest-status classes may have moved closer to the mean.

Here is the paper by Lindsay Paterson, British data, and for the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis.

“America Needs a New Scientific Revolution”

That is the title of the new Derek Thompson piece in The Atlantic. Here is one excerpt:

The existing layers of bureaucracy have obvious costs in speed. They also have subtle costs in creativity. The NIH’s pre-grant peer-review process requires that many reviewers approve of an application. This consensus-oriented style can be a check against novelty—what if one scientist sees extraordinary promise in a wacky idea but the rest of the board sees only its wackiness? The sheer amount of work required to get a grant also penalizes radical creativity. Many scientists, anticipating the turgidity and conservatism of the NIH’s approval system, apply for projects that they anticipate will appeal to the board rather than pour their energies into a truly new idea that, after a 500-day waiting period, might get rejected. This is happening in an academic industry where securing NIH funding can be make-or-break: Since the 1960s, doctoral programs have gotten longer and longer, while the share of Ph.D. holders getting tenure has declined by 40 percent.

And:

First is the trust paradox. People in professional circles like saying that we “believe the science,” but ironically, the scientific system doesn’t seem to put much confidence in real-life scientists. In a survey of researchers who received Fast Grants, almost 80 percent said that they would change their focus “a lot” if they could deploy their grant money however they liked; more than 60 percent said they would pursue work outside their field of expertise, against the norms of the NIH. “The current grant funding apparatus does not allow some of the best scientists in the world to pursue the research agendas that they themselves think are best,” Collison, Cowen, and the UC Berkeley scientist Patrick Hsu wrote in the online publication Future in June. So major funders have placed researchers in the awkward position of being both celebrated by people who say they love the institution of science and constrained by the actual institution of science.

Much of the rest of the piece is a discussion of Fast Grants and also biomedical funding more generally.

Friday assorted links

2. Photo trip to the Faroe Islands.

3. Tungsten cube sells for 250k. It’s heavy.

5. NYT Anthony Downs obituary. “Drawing from his stash of some 200 joke books, he would inject, on average, one witticism into his prepared remarks every six minutes.” And he wore two extra wristwatches. And it is also striking how the NYT writer cannot fathom that the median voter theorem is…mostly correct.

Daddy’s girl?

That is the title of a new paper by Maddelena Ronchi and Nina Smith:

We study the role of managers’ gender attitudes in shaping gender inequality within the workplace. Using Danish registry data, we exploit the birth of a daughter as opposed to a son as a plausibly exogeneous shock to male managers’ gender attitudes and compare within-firm changes in women’s labor outcomes depending on the manager’s newborn gender. We find that women’s relative earnings and employment increase by 4.4% and 2.9% respectively following the birth of the manager’s first daughter. These effects are driven by an increase in managers’ propensity to replace male workers by hiring women with comparable education, hours worked, and earnings. In line with managers’ ability to substitute men with comparable women, we do not detect any significant effect on firm performance. Finally, we find evidence of rapid behavioral responses which intensify over time, suggesting that both salience and direct exposure to themes of gender equality contribute to our results.

Note that Ronchi is on the job market this year. Via Jennifer Doleac. I am not sure of the last part of that last sentence (are other mechanisms possible? Maybe these fathers simply become better at understanding female talent?), but still this is an interesting result.

ProPublica on FDA Delay

If you have been following MR for the last 18 months (or 18 years!) you won’t find much new in this ProPublica piece on FDA delay in approving rapid tests but, other than being late to the game, it’s a good piece. Two points are worth emphasizing. First, some of the problem has been simple bureaucratic delay and inefficiency.

![]()

In late May, WHPM head of international sales Chris Patterson said, the company got a confusing email from its FDA reviewer asking for information that had in fact already been provided. WHPM responded within two days. Months passed. In September, after a bit more back and forth, the FDA wrote to say it had identified other deficiencies, and wouldn’t review the rest of the application. Even if WHPM fixed the issues, the application would be “deprioritized,” or moved to the back of the line.

“We spent our own million dollars developing this thing, at their encouragement, and then they just treat you like a criminal,” said Patterson. Meanwhile, the WHPM rapid test has been approved in Mexico and the European Union, where the company has received large orders.

An FDA scientist who vetted COVID-19 test applications told ProPublica he became so frustrated by delays that he quit the agency earlier this year. “They’re neither denying the bad ones or approving the good ones,” he said, asking to remain anonymous because his current work requires dealing with the agency.

Recall my review of Joseph Gulfo’s Innovation Breakdown.

Second, the FDA has engaged in regulatory nationalism–refusing to look at trial data from patients in other countries. This is madness when India does it and madness when the US does it.

For example, the biopharmaceutical giant Roche told ProPublica that it submitted a home test in early 2021, but it was rejected by the FDA because the trials had been done partly in Europe. The test had compared favorably with Abbott’s rapid test, and received European Union approval in June. The company plans to resubmit an application by the end of the year.

A smaller company, which didn’t want to be named because it has other contracts with the U.S. government, withdrew its pre-application for a rapid antigen test with integrated smartphone-based reporting because it heard its trial data from India — collected as the delta variant was surging there — wouldn’t be accepted. Doing the trials in the U.S. would have cost millions.

Photo credit: MaxPixel.

The teleshock

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one part:

If you have had a relatively comfortable job during the pandemic, it might now be time to worry.

The more culturally specific your knowledge and skills, however, the more protected you will be. Doing math and writing code are universal skills. But if you are a wedding consultant, even an online wedding consultant, you’re probably not going to lose business to a competitor from Zimbabwe, no matter how sharp. On the whole, more people will end up in jobs that feel very “American,” for lack of a better word. Legally protected sectors — law, medicine and other professions requiring occupational licenses — will also get more crowded.

Among the winners will be American managers, shareholders and consumers. Managers will be able to hire the world’s best talent, at least from the English-speaking world, while productivity gains will translate into more profitable companies and better and cheaper products.

Big business will likely benefit more than small business. The larger companies have the networks and the brand names to attract the best overseas talent. And if a worker overseas cannot perform all the functions of a particular job, a larger company can more easily fill in the gaps with other talent.

It will also be very good for American U.S. soft power. The U.S. has a lot of successful, well-known multinational corporations. Think of all the many people around the world who might like to work for Apple, for example. American culture also seems to produce highly talented managers, and U.S. business is used to working with people from many different cultures. (This is in contrast to, say, Japan, which will not benefit as much as the U.S. from the teleshock, while Anglophone-friendly countries such as Sweden and the Netherlands may do well.)

The teleshock is likely to continue for a considerable period of time, perhaps longer than the China shock. It is conventional wisdom that “software is eating the world.” As software and tech become larger and more important, more of their jobs can be outsourced. The process will have no natural end. Furthermore, more people in the world will learn English, including in low-wage countries, so the potential competitive supply of affordable workers will not be exhausted anytime soon.

Recommended.

Our regulatory state is failing us, edition #1637

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the SalivaDirect PCR COVID-19 test created by the Yale School of Public Health for use with pooled saliva samples.

Pooled testing allows labs to combine saliva samples from multiple individuals into a single tube and process the batch as a single test. This approach maintains the clinical sensitivity associated with the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction tests — the gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 — and gives labs the ability to process the tests far more quickly. The FDA authorizes Yale-designated laboratories to use the SalivaDirect test to pool as many as five samples at a time for SARS-CoV-2 testing.

That is November 2021. In July 2020, Alex wrote: “Tyler and I have been pushing pooled testing for months.”

Better to have nothing in the meantime I guess! In the meantime, only a handful of pooled spit tests have been approved.

Here is the full piece, via DR.

Thursday assorted links

1. Twenty new words for the dictionary.

2. “We find that while people with BD [bipolar disorder] are 20 percent less likely to be active in any creative occupation than the population, they are 50 percent more likely to be composers and musicians. Occupations that people with BD are most likely to pursue, instead, include clerks, librarians, archivists and curators, as well as waiters and bartenders. Notably, we also find that the healthy siblings of people with BD are 11 percent more likely to work in creative professions…” Link here.

3. Carbon capture update? (NYT)

4. Econ classes from left wing to right wing? And Hispanic New Jersey voters. Passaic County.

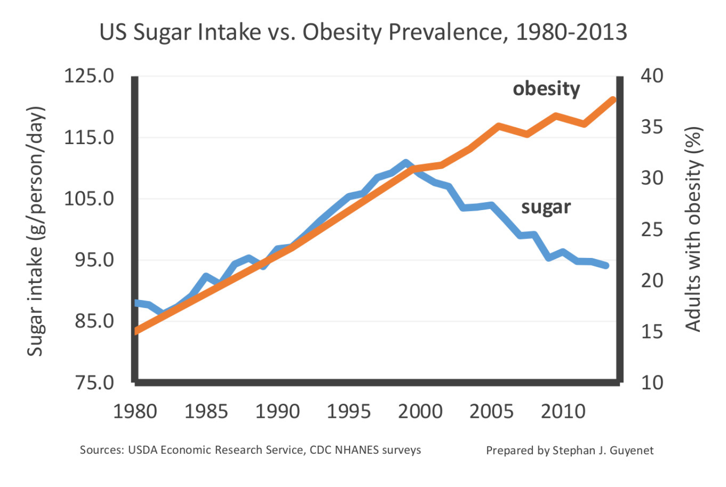

Sugar Consumption

From Paul Kedrosky this graph which casts doubt on a sugar mono-causal theory of obesity. Yes, it includes corn syrup.:

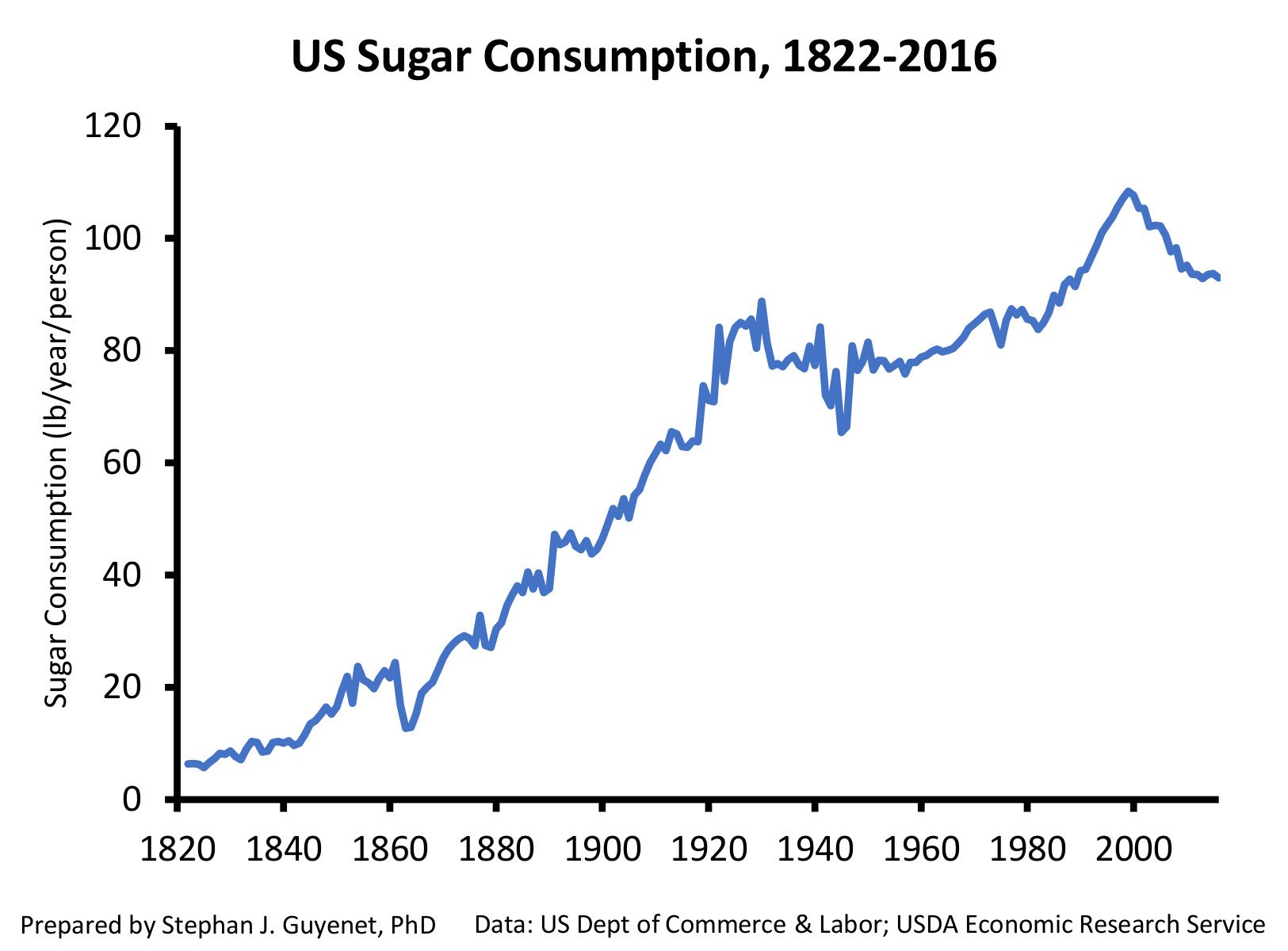

A longer series, also from Stephan Guyenet, shows that we are well above historical averages in sugar consumption even after the more recent decline. Obesity didn’t really increase from say to 1820-1920, however.

A longer series, also from Stephan Guyenet, shows that we are well above historical averages in sugar consumption even after the more recent decline. Obesity didn’t really increase from say to 1820-1920, however.

Claims about the costs of global warming

We quantify global and regional aggregate damages from global warming of 1.5 to 4 °C above pre-industrial levels using a well-established integrated assessment model, PAGE09. We find mean global aggregate damages in 2100 of 0.29% of GDP if global warming is limited to about 1.5 °C (90% confidence interval 0.09–0.60%) and 0.40% for 2 °C (range 0.12–0.91%). These are, respectively, 92% and 89% lower than mean losses of 3.67% of GDP (range 0.64–10.77%) associated with global warming of 4 °C. The net present value of global aggregate damages for the 2008–2200 period is estimated at $48.7 trillion for ~ 1.5 °C global warming (range $13–108 trillion) and $60.7 trillion for 2 °C (range $15–140 trillion). These are, respectively, 92% and 90% lower than the mean NPV of $591.7 trillion of GDP for 4 °C warming (range $70–1920 trillion). This leads to a mean social cost of CO2 emitted in 2020 of ~ $150 for 4 °C warming as compared to $30 at ~ 1.5 °C warming. The benefits of limiting warming to 1.5 °C rather than 2 °C might be underestimated since PAGE09 is not recalibrated to reflect the recent understanding of the full range of risks at 1.5 °C warming.

That is from a new paper by R. Warren, et.al. The model does cover uncertainty, quadratic damages, and other features to steer it away from denialism. At the end of the calculation, however, for a temperature rise of three degrees Centigrade they still find a mean damage of 2% of global gdp, and a range leading up to three percent of global gdp in terms of foregone consumption. That is plausibly one year’s global growth.

If I understand them correctly, and I am not sure I do: “These give initial mean consumption discount rates of around 3% per year in developed regions and 48% [!] in developing ones.” And what are the non-initial rates? I just don’t follow the paper here, but probably I do not agree with it. Perhaps at least for the developed nations this is a useful upper bound for costs? And it is not insanely high.

Here is a piece by Johannes Ackva and John Halstead, “Good news on climate change.” Excerpt:

However, for a variety of reasons, SSP5-RCP8.5 [a kind of worst case default path] now looks increasingly unlikely as a ‘business as usual’ emissions pathway. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the costs of renewables and batteries have declined extremely quickly. Historically, models have been too pessimistic on cost declines for solar, wind and batteries: out of nearly 3,000 Integrated Assessment Models, none projected that solar investment costs (different to the levelised costs shown below) would decline by more than 6% per year between 2010 and 2020. In fact, they declined by 15% per year.

And:

Fundamentally, existing mainstream economic models of climate change consistently fail to model exponential cost declines, as shown on the chart below. The left pane below shows historical declines in solar costs compared to Integrated Assessment Model projections of costs. The pane on the right shows the cost of solar compared to Integrated Assessment Model assessments of ‘floor costs’ for solar – the lowest that solar could go. Real world solar prices have consistently smashed through these supposed floors.

…in order for us to follow SSP5-RCP8.5, there would have to be very fast economic growth and technological progress, but meagre progress on low carbon technologies. This does not seem very plausible. In order to reproduce SSP5-8.5 with newer models, the models had to assume that average global income per person will rise to $140,000 by 2100 and also that we would burn large amounts of coal.

And: “Global CO2 emissions have been flat for a decade, new data reveals.” Again, better than previous projections.

As I said in the title of this post, these are “Claims.” But overall I would say that the new results are slanting modestly in the less negative direction, though I am not sure that the headlines of the last two weeks are equally encouraging.

My Conversation with David Salle

I was honored to visit his home and painting studio, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the CWT summary:

David joined Tyler to discuss the fifteen (or so) functions of good art, why it’s easier to write about money than art, what’s gone wrong with art criticism today, how to cultivate good taste, the reasons museum curators tend to be risk-averse, the effect of modern artistic training on contemporary art, the evolution of Cézanne, how the centrality of photography is changing fine art, what makes some artists’ retrospectives more compelling than others, the physical challenges of painting on a large scale, how artists view museums differently, how a painting goes wrong, where his paintings end up, what great collectors have in common, how artists collect art differently, why Frank O’Hara was so important to Alex Katz and himself, what he loves about the films of Preston Sturges, why The Sopranos is a model of artistic expression, how we should change intellectual property law for artists, the disappointing puritanism of the avant-garde, and more.

And excerpt:

COWEN: Yes, but just to be very concrete, let’s say someone asks you, “I want to take one actionable step tomorrow to learn more about art.” And they are a smart, highly educated person, but have not spent much time in the art world. What should they actually do other than look at art, on the reading level?

SALLE: On the reading level? Oh God, Tyler, that’s hard. I’ll have to think about it. I’ll have to come back with an answer in a few minutes. I’m not sure there’s anything concretely to do on the reading level. There probably is — just not coming to mind.

There’s Henry Geldzahler, who wrote a book very late in his life, at the end of his life. I can’t remember the title, but he addresses the problem of something which is almost a taboo — how do you acquire taste? — which is, in a sense, what we’re talking about. It’s something one can’t even speak about in polite society among art historians or art critics.

Taste is considered to be something not worth discussing. It’s simply, we’re all above that. Taste is, in a sense, something that has to do with Hallmark greeting cards — but it’s not true. Taste is what we have to work with. It’s a way of describing human experience.

Henry, who was the first curator of modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, was a wonderful guy and a wonderful raconteur. Henry basically answers your question: find ways, start collecting. “Okay, but I don’t have any money. How can I collect art?” You don’t have to collect great paintings. Just go to the flea market and buy a vase for 5 bucks. Bring it back to your room, live with it, and look at it.

Pretty soon, you’ll start to make distinctions about it. Eventually, if you’re really paying attention to your own reactions, you’ll use it up. You’ll give that to somebody else, and you’ll go back to the flea market, and you buy another, slightly better vase, and you bring that home and live with that. And so the process goes. That’s very real. It’s very concrete.

And:

COWEN: As you know, the 17th century in European painting is a quite special time. You have Velásquez, you have Rubens, you have Bruegel, much, much more. And there are so many talented painters today. Why can they not paint in that style anymore? Or can they? What stops them?

SALLE: Artists are trained in such a vastly different way than in the 17th, 18th, or even the 19th century. We didn’t have the training. We’re not trained in an apprentice guild situation where the apprenticeship starts very early in life, and people who exhibit talent in drawing or painting are moved on to the next level.

Today painters are trained in professional art schools. People reach school at the normal age — 18, 20, 22, something in grad school, and then they’re in a big hurry. If it’s something you can’t master or show proficiency in quickly, let’s just drop it and move on.

There are other reasons as well, cultural reasons. For many years or decades, painting in, let’s say, the style of Velásquez or even the style of Manet — what would have been the reason for it? What would have been the motivation for it, even assuming that one could do it? Modernism, from whenever we date it, from 1900 to 1990, was such a persuasive argument. It was such an inclusive and exciting and dynamic argument that what possibly could have been the reason to want to take a step back 200 years in history and paint like an earlier painter?

It is a bit slow at the very beginning, otherwise excellent throughout.