Month: April 2023

The One-Child Policy and Intergenerational Mobility in China

We examine whether and how the world’s largest population planning program, the One-Child Policy, has shaped intergenerational mobility in China. Using a dataset with 2,096,798 childparent(s) pairs combined from various rounds of ten separate national household surveys, we leverage exogenous variation in fine rates imposed for One-Child Policy violations across provinces to study causal impacts of the One-Child Policy on intergenerational persistence. Using a continuous difference-in-differences approach, we find that for cohorts born between 1980 and 1996, the One-Child Policy reduced persistence in intergenerational income, education, and social class, comparing to those born prior to 1979. We estimate that the overall effect of the One-Child Policy fines was to reduce persistence in intergenerational income, education, and social class by 28.1%, 48.7%, and 24.8%, respectively. Analyzing mechanisms, we find that the One-Child Policy boosted China’s intergenerational mobility by diminishing elite family heirship, concentrating resources for lower-income families, and decreasing returns to education. The One-Child Policy has brought about a significant socioeconomic reshuffle that has reshaped the role of China’s longstanding class solidification.

That is from a recent paper by Shanthi Manian, Qi Zhang, and Bin Zhao. Via Linghui Han. Might some similar results be true for any other low-fertility societies? Or are the environments too disparate?

Monday assorted links

2. Why you should teach at a community college.

3. Fewer Jews in the Ivy League, though up at Brown.

4. La Nacion interview with me (in Spanish). And new re-review of Notorious Byrd Brothers.

5. Chris Hughes (earlier of Facebook) is now an academic Arthur Burns revisionist? (NYT)

7. Dating apps with AI? And recurrent memory transformers?

8. “So experts doubt that the measures will be tightly enforced.” (The Economist, on Chinese AI restrictions)

Tenured professor has salary reduced to zero

Math professor Harold Donnelly is still listed on Purdue University’s website—but fellow math professors have shared something odd about his salary.

It’s $0, after the university began reducing it in fall 2021, according to emails these professors provided.

“I have carefully considered your career of contributions to mathematics and to our department, college and university,” says a July 2021 email from a math department head, whose name is redacted, about the first salary slash, a 20 percent cut. Irena Swanson, who was the department head then and now, didn’t return requests for comment Friday.

Here is the full story. File under “What, no clawback!?”

Voters as Mad Scientists: Essays on Political Irrationality

Bryan Caplan’s latest collection of essays, Voters as Mad Scientists: Essays on Political Irrationality is out and, as the kids say, it’s a banger. Voters as Mad Scientists includes classics on social desirability bias, the ideological Turing test, the Simplistic Theory of Left and Right and more. Lots of wisdom in these short essays. Bryan is a pundit who writes for the long run. Here’s one on the historically hollow cries of populism:

Bryan Caplan’s latest collection of essays, Voters as Mad Scientists: Essays on Political Irrationality is out and, as the kids say, it’s a banger. Voters as Mad Scientists includes classics on social desirability bias, the ideological Turing test, the Simplistic Theory of Left and Right and more. Lots of wisdom in these short essays. Bryan is a pundit who writes for the long run. Here’s one on the historically hollow cries of populism:

History textbooks are full of populist complaints about business: the evils of Standard Oil, the horrors of New York tenements, the human body parts in Chicago meat packing plants. To be honest, I haven’t taken these complaints seriously since high school….Still, I periodically wonder if my nonchalance is unjustified. Populists rub me the wrong way, but how do I know they didn’t have a point? After all, I have near-zero first-hand knowledge of what life was like in the heyday of Standard Oil, New York tenements, or Chicago meat-packing. What would I have thought if I was there?

Yet, Bryan continues, there is a test. What do populists say about the technological revolutions of the 2000s which Bryan has seen with this own eyes?

I’ve seen the tech industry dramatically improve human life all over the world.

Amazon is simply the best store that ever existed, by far, with incredible selection and unearthly convenience. The price: cheap.

Facebook, Twitter, and other social media let us socialize with our friends, comfortably meet new people, and explore even the most obscure interests. The price: free.

Uber and Lyft provide high-quality, convenient transportation. The price: really cheap.

Skype is a sci-fi quality video phone. The price: free. YouTube gives us endless entertainment. The price: free.

Google gives us the totality of human knowledge! The price: free.

That’s what I’ve seen. What I’ve heard, however, is totally different. The populists of our Golden Age are loud and furious. They’re crying about “monopolies” that deliver fire-hoses worth of free stuff. They’re bemoaning the “death of competition” in industries (like taxicabs) that governments forcibly monopolized for as long as any living person can remember. They’re insisting that “only the 1% benefit” in an age when half of the high-profile new businesses literally give their services away for free. And they’re lashing out at businesses for “taking our data” – even though five years ago hardly anyone realized that they had data.

My point: If your overall reaction to business progress over the last fifteen years is even mildly negative, no sensible person will try to please you, because you are impossible to please. Yet our new anti-tech populists have managed to make themselves a center of pseudo-intellectual attention.

Read the whole thing and follow Bryan at Bet On It.

The polity that is Russian markets in everything

In Russian prisons, they said they were deprived of effective treatments for their H.I.V. On the battlefield in Ukraine, they were offered hope, with the promise of anti-viral medications if they agreed to fight.

It was a recruiting pitch that worked for many Russian prisoners.

About 20 percent of recruits in Russian prisoner units are H.I.V. positive, Ukrainian authorities estimate based on infection rates in captured soldiers. Serving on the front lines seemed less risky than staying in prison, the detainees said in interviews with The New York Times.

Here is the full NYT story. And here is how it unfolded:

Timur had no military experience and was provided two weeks of training before deployment to the front, he said. He was issued a Kalashnikov rifle, 120 bullets, an armored vest and a helmet for the assault. Before sending the soldiers forward, he said, commanders “repeated many times, ‘if you try to leave this field, we will shoot you.’”

Soldiers in his platoon, he said, were sent on a risky assault, waves of soldiers with little chance of survival sent into battle on the outskirts of the eastern city of Bakhmut. Most were killed on their first day of combat. Timur was captured.

Roughly ten percent of Russia’s incarcerated population has signed up to fight in Ukraine.

Would higher male earnings drive a marriage boom?

The results of that research cast doubt on the notion that an improvement in men’s economic position will necessarily increase marriage rates. The fracking boom of the first decade of the 2000s, which gave rise to economic booms in US towns and cities where they wouldn’t have occurred otherwise, provided a rare opportunity to investigate whether an improvement in the economic prospects of men without a four-year college degree would lead to a reduction in the nonmarital birth share. In a 2018 study that I wrote with my coauthor Riley Wilson, we used a fracking boom to test a “reverse marriageable men” hypothesis…

Our first finding was that these local fracking booms led to overall increases in total births, an increase of roughly 3 births per 1,000 women…

To our surprise, the increase in births associated with fracking booms occurred as much with unmarried partners as with married ones. The “reverse marriageable men” hypothesis, which predicted that improvements in the economic circumstances of men would lead to an increase in marriage and a reduction in the share of births outside marriage, was not what the data showed.

That is from Melissa Kearney, The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. Here is the original research. Note also that pp.96-100 of this book provide strong evidence against the claim that the welfare state has been driving the rise in single-parent families.

De-dollarization?

The killer chart from @Brad_Setser is this: https://t.co/t7FI7L4Xsz pic.twitter.com/0NqNMkOQkg

— Niall Ferguson (@nfergus) April 23, 2023

Sunday assorted links

1. How quickly can people make accurate moral judgments?

2. News headlines becoming much more negative precedes teen depression rise. (To be clear that is my take, not that of the authors. You can think of this as a reason why I am not so persuaded by the Haidt hypothesis.)

3. Greg Brockman ChatGPT talk, mostly on plug-ins.

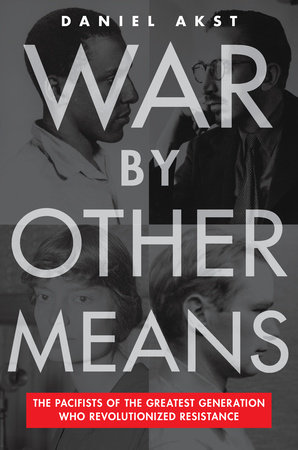

War by Other Means

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In The Trial of The Chicago Seven, the Aaron Sorkin movie about the group of anti–Vietnam War protesters charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the focus is on the antics of Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong). It’s a good movie but their story is not the only story. Among the Chicago Seven was an older, quieter, more bemused David Dellinger (played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch). It was not Dellinger’s first trial. In 1940 Dellinger had refused to register for the then-new draft, the first peacetime draft in America’s history, and he had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector and pro-pacifism protester. Dellinger served a year in federal prison in Danbury, CT, and upon his release, he adamantly refused to register once more. He was imprisoned for an additional two years in the maximum-security facility at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in hunger strikes and endured periods of solitary confinement. Dellinger was the real deal.

In War by Other Means, Daniel Akst recaptures an older generation of anti-war, pro-pacifism protesters; people like Dellinger, the radical Catholic Dorothy Day, Bayard Rustin, Dwight MacDonald and others. This earlier group grew out of the disillusionment that many Americans felt after World War One–they resolved to never again be entangled in European death and destruction.

During the interwar period, moreover, the United States had developed perhaps the largest and best-organized pacifist movement in the world. Pacifism was part of the curriculum at some schools and firmly on the agenda of the mainline Protestant denominations that were such important institutions in the life of this churchgoing nation at the time….Pacifism was well established on campuses thanks to a massive and diverse national student anti-war movement….During the thirties pacifism, probably surpassed even the Depression as the dominant social issue in American liberal Protestantism…

It wasn’t just liberal Protestants, Pacifism also drew on the isolationist tradition:

…isolationism simply wanted to keep America out of other peoples’ bloody conflicts; it advocated strength through preparedness and put faith in the vastness of the oceans to keep us safe. “Isolationism” has become a dirty word since its heyday in the thirties, when it came into common usage. But in fact it started life as a pejorative, one used by American expansionists in the late nineteenth century to tar the righteous killjoys who objected to burgeoning US imperialism…

Regrettably, the unique blend of “left-wing” pacifism and “right-wing” isolationism, once prevalent in America, has largely vanished. Mostly vanished also is–for want of better terms–the Christian and left-wing libertarianism of people like Dellinger, Day and MacDonald, who although being on the left and hardly pro-market had a deep appreciation for individualism and civil society and a fear of the homogenizing and brutalizing role of the state.

Daniel Akst’s War by Other Means is an important and engaging look at a cast of remarkable American characters and their unique blend of ideological pacifism.

Addendum: Nick Gillespie at Reason has a very good interview with Akst.

Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst

Social media fueled a bank run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and the effects were felt broadly in the U.S. banking industry. We employ comprehensive Twitter data to show that preexisting exposure to social media predicts bank stock market losses in the run period even after controlling for bank characteristics related to run risk (i.e., mark-to-market losses and uninsured deposits). Moreover, we show that social media amplifies these bank run risk factors. During the run period, we find the intensity of Twitter conversation about a bank predicts stock market losses at the hourly frequency. This effect is stronger for banks with bank run risk factors. At even higher frequency, tweets in the run period with negative sentiment translate into immediate stock market losses. These high frequency effects are stronger when tweets are authored by members of the Twitter startup community (who are likely depositors) and contain keywords related to contagion. These results are consistent with depositors using Twitter to communicate in real time during the bank run.

That is from a new paper by J. Anthony Cookson, et.al. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Brian Slesinsky on AI taxes (from my email)

My preferred AI tax would be a small tax on language model API calls, somewhat like a Tobin tax on currency transactions. This would discourage running language models in a loop or allowing them to “think” while idle.

For now, we mostly use large language models under human supervision, such as with AI chat. This is relatively safe because the AI is frozen most of the time [1]. It means you get as much time as you like to think about your next move, and the AI doesn’t get the same advantage. If you don’t like what the AI is saying, you can simply close the chat and walk away.

Under such conditions, a sorcerer’s apprentice shouldn’t be able to start anything they can’t stop. But many people are experimenting with running AI in fully automatic mode and that seems much more dangerous. It’s not yet as dangerous as experimenting with computer viruses, but that could change.

Such a tax doesn’t seem necessary today because the best language models are very expensive [2]. But making and implementing tax policy takes time, and we should be concerned about what happens when costs drop.

Another limit that would tend to discourage dangerous experiments would be a minimum reaction time. Today, language models are slow. It reminds me of using a dial-up modem in the old days. But we should be concerned about what happens when AI’s start reacting to events much quicker than people.

Different language models quickly reacting to each other in a marketplace or forum could cause cascading effects, similar to a “flash crash” in a financial market. On social networks, it’s already the case that volume is far higher than we can keep up with. But it could get worse when conversations between AI’s start running at superhuman speeds.

Financial markets don’t have limits on reaction time, but there are trading hours and circuit breakers that give investors time to think about what’s happening in unusual situations. Social networks sometimes have rate limits too, but limiting latency at the language model API seems more comprehensive.

Limits on transaction costs and latency won’t make AI safe, but they should reduce some risks better than attempting to keep AI’s from getting smarter. Machine intelligence isn’t defined well enough to regulate. There are many benchmarks and it seems unlikely that researchers will agree on a one-dimensional measurement, like IQ in humans.

[1] https://skybrian.substack.com/p/ai-chats-are-turn-based-games

[2] Each API call to GPT4 costs several cents, depending on how much input you give it.

Running a smaller language model on your own computer is cheaper, but they are lower quality, and it has opportunity costs since it keeps the computer busy.

Fertility and mimetic desire

There is a new and excellent NYT column by Peter Coy on this topic, here is one excerpt:

There is a town in western Japan named Nagi that’s famous for making babies. Its fertility rate in 2021 was 2.68 lifetime births per woman, compared with 1.3 for Japan as a whole, according to an article in The Wall Street Journal that my Opinion colleague Jessica Grose recently cited. Delegations from elsewhere in Japan and abroad have come to Nagi to learn its secret formula. Is it the free medical care for all children? The affordable child care? The cash gifts to new mothers?

I’ve been considering another theory. Maybe people in Nagi are having babies because other people in Nagi are having babies.

And:

I read several papers on peer effects on fertility with Angrist’s caveats in mind. One, by Jason Fletcher and Olga Yakusheva, looked at American teenagers and found that a 10 percentage point increase in pregnancies of classmates is associated with a 2 to 5 percentage point greater likelihood of a teenager herself becoming pregnant.

The complications behind such inferences are considered in detail.

Saturday assorted links

1. “Schumacher family planning legal action over AI ‘interview’ with F1 great.”

2. More Brian Potter on how solar power got cheap.

3. “In a study to be published this summer, they find that the median ai expert gave a 3.9% chance to an existential catastrophe (where fewer than 5,000 humans survive) owing to ai by 2100. The median superforecaster, by contrast, gave a chance of 0.38%.” From The Economist.

4. New charter city for Nigeria? (p.s. silly header on the article). And some CCI corrections to the piece.

The link between economic concentration and political power?

Our findings do not support the political antitrust movement’s central hypothesis that there is an association between economic concentration and the concentration of lobbying power. We do not find a strong relationship between economic concentration and the concentration of lobbying expenditure at the industry level. Nor do we find a significant difference between top firms’ and other firms’ allocation of additional revenues to lobbying. And we find no evidence that increasing economic concentration has appreciably restricted the ability of smaller players to seek political influence through lobbying. Ultimately, our findings show that the political antitrust movement’s claims do not rest on a solid empirical foundation in the lobbying context. Our findings do not allay all concerns about transformation of economic power into political power, but they show that such transformation is not straightforward, and they counsel caution about reshaping antitrust law in the name of protecting democracy.

Here is the recent paper by Sepehr Shahshahani and Nolan McCarthy. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis. And yes, yes I know there is much more here than just lobbying expenditures, but that it doesn’t show up in that area…isn’t supportive.

AI and economic liability

I’ve seen a number of calls lately to place significant liability on the major LLM models and their corporate owners, and so I cover that topic in my latest Bloomberg column. There are numerous complications, and I cover a mere smidgen of them, but still more analytics are needed here. Excerpt:

Imagine a bank robbery that is organized through emails and texts. Would the email providers or phone manufacturers be held responsible? Of course not. Any punishment or penalties would be meted out to the criminals…

In the case of the bank robbery, the providers of the communications medium or general-purpose technology (i.e., the email account or mobile device) are not the lowest-cost avoiders and have no control over the harm. And since general-purpose technologies — such as mobile devices or, more to the point, AI large language models — have so many practical uses, the law shouldn’t discourage their production with an additional liability burden.

Of course there are many more complications, and I am not saying zero corporate liability is always correct. But we do need to start with the analytics, and a simple fear of AI-related consequences does settle the matter. There is this:

On a more practical level, liability assignment to the AI service just isn’t going to work in a lot of areas. The US legal system, even when functioning well, is not always able to determine which information is sufficiently harmful. A lot of good and productive information — such as teaching people how to generate and manipulate energy — can also be used for bad purposes.

Placing full liability on AI providers for all their different kinds of output, and the consequences of those outputs, would probably bankrupt them. Current LLMs can produce a near-infinite variety of content across many languages, including coding and mathematics. If bankruptcy is indeed the goal, it would be better for proponents of greater liability to say so.

Here is a case where partial corporate liability may well make sense:

It could be that there is a simple fix to LLMs that will prevent them from generating some kinds of harmful information, in which case partial or joint liability might make sense to induce the additional safety. If we decide to go this route, we should adopt a much more positive attitude toward AI — the goal, and the language, should be more about supporting AI than regulating it or slowing it down. In this scenario, the companies might even voluntarily adopt the beneficial fixes to their output, to improve their market position and protect against further regulatory reprisals.

Again, not the final answers but I am imploring people to explore the real analytics on these questions.