Jeff Sachs reviews Acemoglu and Robinson

As you might expect, he stresses geography rather than institutions:

In places where production is expensive because of an inhospitable climate, unfavorable topography, low population densities, or a lack of proximity to global markets, many technologies from abroad will not arrive quickly through foreign investments or outsourcing. Compare Bolivia and Vietnam in the 1990s, both places I experienced firsthand as an economic adviser. Bolivians enjoyed greater political and civil rights than the Vietnamese did, as measured by Freedom House, yet Bolivia’s economy grew slowly whereas Vietnam’s attracted foreign investment like a magnet. It is easy to see why: Bolivia is a landlocked mountainous country with much of its territory lying higher than 10,000 feet above sea level, whereas Vietnam has a vast coastline with deep-water ports conveniently located near Asia’s booming industrial economies. Vietnam, not Bolivia, was the desirable place to assemble television sets and consumer appliances for Japanese and South Korean companies.

The review is interesting throughout, though I would stress the old saying: “As usual, the truth lies somewhere in between.”

The Hispanic high school graduation rate is increasing

The number of young Hispanics enrolled in college, which surpassed black enrollment for the first time in 2010, jumped to almost 2.1 million last year, from about 1.3 million in 2008. That is partly a product of a swelling Hispanic population, as well as the increased rate of college attendance.

But it also reflects a fast-rising high school graduation rate. In the 1990s, fewer than 60 percent of Hispanics 18 to 24 had a high school diploma, but that figure hit 70 percent for the first time in 2009, and 76 percent last year.

Here is a bit more.

Education as loss leader?

And then there is the Walt Disney Company. It is building a chain of language schools in China big enough to enroll more than 150,000 children annually. The schools, which weave Disney characters into the curriculum, are not going to move the profit needle at a company with $41 billion in annual revenue. But they could play a vital role in creating a consumer base as Disney builds a $4.4 billion theme park and resort in Shanghai.

Here is more, mostly on whether media companies enjoy any synergies in education markets, interesting throughout.

Assorted links

1. Who dies from Russian roulette?

2. Interview with the new GMU President, Ángel Cabrera.

3. Lawrence Summers on government growth (very good piece), or try this link, and a Reihan follow-up.

4. Sokurov’s Faust will be out on DVD soon, it has received rave reviews.

5. Updated results on right to carry laws, and Medicaid seems to improve black child mortality but perhaps not white child mortality.

Evan Soltas is now writing for Bloomberg

Here is his excellent column on decentralized provincial health care provision in Canada. Excerpt:

By fixing the maximum federal contribution, block grants offer Canada’s provincial and territorial governments far better incentives to reduce the cost and improve the quality of the medical services they purchase. When costs rise, the provinces that run the programs are forced to pay 100 percent of the added costs at the margin, unlike in the U.S., where state governments pay an average of 43 cents at the margin for every dollar of added Medicaid expense.

Decentralized administration gives provinces the flexibility and the accountability to design their programs according to their needs and particular local challenges, rather than federal “one-size-fits-none” imposition. It also creates opportunities for innovation. By sharing notes, provinces and territories learn from one another and improve their Medicare programs.

Canada has been using block grants for 35 years. After several years of ruinously high growth in Medicare expenses during the 1970s, their federal government abandoned a 50-50 cost-sharing plan in 1977. Through the Canada Health Transfer program, which gives states some money directly and some through tax-shifting agreements, Canadian provinces and territories receive equal per capita aid, regardless of actual health care expenditure.

Hat tip goes to Miles Kimball.

Does new information slow down your life?

From William Reville, here is a speculation:

Finally, here is a “guaranteed” way to lengthen your life. Childhood holidays seem to last forever, but as you grow older time seems to accelerate. “Time” is related to how much information you are taking in – information stretches time. A child’s day from 9am to 3.30pm is like a 20-hour day for an adult. Children experience many new things every day and time passes slowly, but as people get older they have fewer new experiences and time is less stretched by information. So, you can “lengthen” your life by minimising routine and making sure your life is full of new active experiences – travel to new places, take on new interests, and spend more time living in the preset.

Most of the short article considers why “the return journey” often seems to run by much faster.

Recent figures on capacity utilization

Industrial production picked up in July after two months of slight growth, the Federal Reserve said Wednesday in the latest reading that shows the economy in the third quarter got off to a decent start. Industrial production picked up 0.6% in July after slender 0.1% monthly gains in May and June, the Fed said. The Fed had previously reported a 0.4% gain in June and a 0.2% drop in May. The 0.6% gain was as expected in a MarketWatch-compiled poll of economists. Capacity utilization rose to 79.3% in July from 78.9% in May – the highest level since April 2008. Even so, it’s still 1% below its average from 1972 to 2011.

The link is here. It suggests there is excess capacity, but not in wild amounts. Elsewhere, in China:

Capacity utilisation has dropped from about 80% before the crisis to a mere 60% in 2011. That compares with about 78.9% for the US currently for total industry (which is not very high by US’s historical average), and 66.8% at the financial crisis trough according to the Federal Reserve. In other words, current capacity utilisation in China appears to be even lower than that of the US during the 2008/09 financial crisis.

Beware all Chinese numbers, but still that cannot be taken as a good sign. Note that the real estate bubble probably is not fundamental to the Chinese economic crisis (though it is a problem), but excess capacity is.

Assorted links

To the point (Austro-Chinese business cycle theory)

“There is persuasive evidence to conclude that the Chinese economy is actually growing at just 4 or 5 per cent right now based on a composite of other indicators,” says Patrick Chovanec, a business professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

“Of China’s 9.2 per cent GDP growth in 2011, 5 percentage points came from investment which means that if China builds just as many roads, bridges, condos and villas as it built last year and no more it will knock five points of this year’s GDP growth. Growth is dependent on ever-rising levels of investment in an environment where that investment is not creating adequate returns.”

That is from the FT. Does this paragraph reassure you?:

Officials and state media reports have suggested local governments will be able to compensate for slumping exports and real estate construction by embarking on a new infrastructure building binge.

What I’ve not been reading

These books have been sent to me, they appear to be of high quality, but they are still sitting in my pile:

1. Nicolai Foss and Peter Klein, Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm.

2. Peter Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD.

3. Barry Cunliffe, Britain Begins.

4. David R. Montgomery, The Rocks Don’t Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah’s Flood.

5. Evan F. Koenig, Robert Leeson, and George A. Kahn, editors, The Taylor Rule and the Transformation of Monetary Policy.

6. Martin B. Gold, Forbidden Citizens: Chinese Exclusion and the U.S. Congress: A Legislative History.

Solve for the equilibrium

…the Romney campaign went up with an ad just days after the Ryan pick, hitting Obama on the $716 billion figure.

“You paid into Medicare for years: every paycheck. Now, when you need it, Obama has cut $716 billion dollars from Medicare. Why? To pay for Obamacare,” the ad says. “The Romney-Ryan plan protects Medicare benefits for today’s seniors and strengthens the plan for the next generation.”

How the GOP ticket talks about Medicare is vitally important in Florida in particular, a competitive swing state with a high retirement-age population. Ryan is visiting the state for the first time today since he was named to the ticket, and will go to The Villages — billed as the largest retirement community in the world — with his mom.

But instead of wading into the policy details with which Ryan is most comfortable, Republican strategists said it would be far smarter for the Wisconsin lawmaker to focus on the Obama move to remove money from the Medicare trust fund and portray Republicans as the program’s savior.

Assorted links

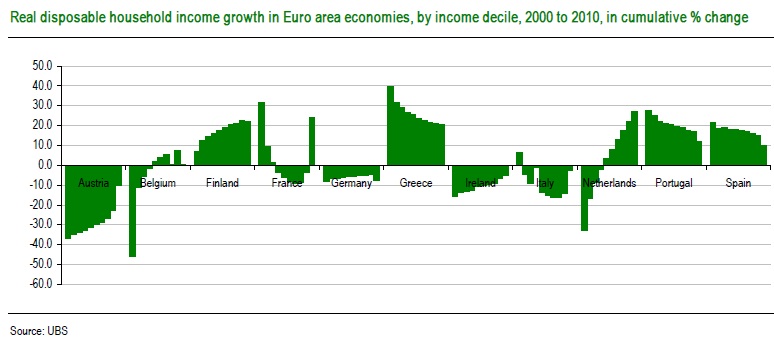

Who gained the most from the euro?

Looking at the growth of real incomes over the first few years of the Euro’s existence, it is hard to argue against the idea that the peripheral countries should be taking more pain now. Core countries have had to accept a decline in real living standards, and it seems unrealistic to expect them to finance an increase in living standards for others.

Here is much more. I don’t agree with all of their methods of assessment, but the piece makes some important (and valid) points.

For all the talk about how much German has benefited from the euro, we learn:

What Donovan and co found is that the lowest-income sections of the more “core” countries saw negative real disposable income growth, while those at the other end of the income scale saw incomes rise still further. In other words, in the core countries, the rich got richer, the poor got poorer.

In other contexts, this pattern is not usually considered a benefit at all. Brad Plumer adds comment, as does Angus.

Posner on Skidelsky and Keynes and leisure time

This review is a fun rant about whether we would be better off with lower incomes and more leisure time. Here is one excerpt:

…I well remember as recently as the 1980s how shabby England was, how terrible the plumbing, how shoddy the housing materials, how treacherously uneven the floors and sidewalks, how inadequate the heating and poor the food — and how tolerant the English were of discomfort. I recall breakfast at Hertford College, Oxford, in an imposing hall with a large broken window — apparently broken for some time — and the dons huddled sheeplike in overcoats; and in a freezing, squalid bar in the basement of the college a don in an overcoat expressing relief at being home after a year teaching in Virginia, which he had found terrifying because of America’s high crime rate, though he had not been touched by it. I remember being a guest of Brasenose College — Oxford’s wealthiest — and being envied because I had been invited to stay in the master’s guest quarters, only to find that stepping into the guest quarters was like stepping into a Surrealist painting, because the floor sloped in one direction and the two narrow beds in two other directions. I recall the English (now American) economist Ronald Coase telling me that until he visited the United States he did not know it was possible to be warm.

China fact of the day

The Hurun Report, based in Shanghai, tracks the nation’s wealthy and calculates that there were a record 271 billionaires (in U.S. dollars) in China in 2011. A third of the top 50 and five of the top 10 hold official political positions, the report says. “The richer they are, the more political positions they have,” it adds.

Here is more.