Some raw numbers on health care costs

During the past months, a number of important articles have appeared in the healthcare literature on the subject of the recent slowing of health-spending growth in the U.S. In an article in January’s Health Affairs, economists at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services suggest that the recession, even though officially ending in mid-2009, was the major factor in “extraordinarily slow” spending growth of 4.7 percent in 2008 and 3.9 percent in 2010, down from 7.5 percent in 2007 and double-digit growth in the 1980s and 1990s. Also citing recessionary causes, a report from the McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform specifies declines in the rate of overall spending growth for eight consecutive years, from 9.2 percent in 2002 to 4.0 percent in 2009.

As I’ve already mentioned, “too soon to tell” is the correct response. Still, we should be raising our probability that the health care cost curve is (somewhat) being bent.

There is much more at the link. You can read Suderman and Lowrey here.

My dual review of Michael Casey and Daniel Gross

It is from The New York Times Book Review, and it covers Michael J. Casey’s The Unfair Trade: How Our Broken Global Financial System destroys the Middle Class, and Daniel Gross’s Better, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline…and the Rise of a New Economy. My bottom line:

Each of these books illuminates one particular economic story very well, but fails to see the larger and more complex picture.

One excerpt on the Casey book:

But does China deserve so much attention (5 chapters out of the book’s 10)? Casey writes that China “provided the cheap goods needed to sustain the American way of life, as well as the finance to pay for it.” Yet the numbers tell a less dramatic story. Currently, imports from China are measured at about 2.7 percent of consumer spending in America. Furthermore, for each dollar of imports from China, a lot of that money was spent in the United States preparing the import; imagine an iPad designed and marketed from Cupertino, Calif., but counted as an import from China. That leaves Chinese imports, measured in terms of true net impact, at about 1.2 percent of American consumer spending.

One excerpt on the Gross book:

The most probable American economic future is a lot of export success, fantastic wealth for the owners of thriving businesses and persistent productivity problems, and thus high prices, for some major items in consumer budgets. That means more stagnation of real wages at the middle of the income distribution.

Both books are already on the market.

Are health care costs really slowing down?

Sarah Kliff writes:

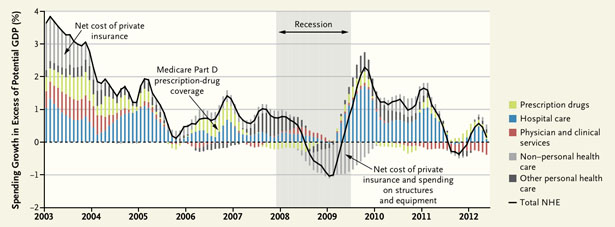

The New England Journal of Medicine published a paper this week titled “When the Cost Curve Bent,” where researchers from the Center for Sustainable Health Costs suggest that the slowdown happened way before the recession. Their analysis shows — and you can see it in this chart — that excess health-care spending growth (any spending above and beyond potential gross domestic product) began to moderate in the early 2000s:

“Too soon to say” is a fair enough response, but this has become increasingly my view over the last year.

Addendum: Angus comments.

1964 predictions about the year 2000

From The New York Times Magazine, excellent visuals and excerpts. As for how the world would look, from today’s vantage point:

It’s surprisingly still more like 1900 out there.

Housemaids, waitresses, and nurses will cease to exist as professions. Fortunately:

By then, the last traces of racial and religious discrimination will have disappeared.

Assorted links

1. Markets in everything, anti-onanism edition.

2. Does personality type predict a professional philosopher’s beliefs?

3. An alternate economic history of the last twenty years, based on automation.

Does the dismal science deserve federal funding?

Here is today’s WSJ Op-Ed by Gary Becker and James Heckman. In general I am sympathetic to government funding for science, but I’d like to tack on a few points to these arguments in particular.

1. There is not a peep about supply elasticity. A lot of economics research comes pretty cheaply and presumably without direct government subsidy. Isn’t the implied conclusion to invest a lot in data gathering and RCTs/field experiments, but not so much in large swathes of economics? Should we not start by listing all those branches of economics which should not be eligible for subsidy?

2. Is there possibly a higher external benefit to directing the attention of economists to teaching or community service rather than research? Somehow this argument ends up underplayed when economists discuss subsidies. Or how about subsidies for economics bloggers? Presumably there is lots of good economics research which remains underpublicized and underutilized. Isn’t that often the relevant choke point, not lack of new research ideas and findings?

3. Economics research is already highly subsidized through our tax code and legal treatment of non-profits. An argument for subsidy is not the same as an argument for further subsidy.

4. I find it easy to believe the subsidies for economists would bring higher returns than the worst uses of federal funds. But surely larger subsidies for economists are not the highest return projects before us. Isn’t it worth listing which projects would be even better than subsidies for economists (or at least acknowledging that they exist)? How about reporting “Subsidies for economists are better than farm subsidies, but not as good as medical R&D subsidies or 347 other uses of the funds”? Presumably the goal is to bring about the best outcome possible, not just to advocate further subsidies for economists, right? Right? Right? After all, that is what the economic method is all about.

Right?

The continuing growth in U.S. exports

And this is from a time of economic turmoil:

The U.S. trade deficit with other countries narrowed to $42.9 billion in June from $48 billion a month earlier, the Commerce Department said Thursday, as imports fell and exports grew. Exports, which have been a pivotal contributor to the economic recovery, were strong almost everywhere except to Europe…

In June, the U.S. notched increases in exports of a variety of goods including pharmaceuticals, cars and industrial engines. Exports increased $1.7 billion to $185 billion, the highest monthly tally ever. Imports declined $3.5 billion to $227.9 billion, driven largely by a drop in oil prices that reduced the value of petroleum imports. Total U.S. exports are up 6% in the first six months of 2012 from the same period a year ago. In the first half of 2011, they were up 16% from the year-earlier period.

Here is more. Here is my earlier American Interest piece on U.S. exporting trends, “What Export-Oriented America Means.”

Crime in Europe and the U.S.

Has there been a “reversal of fortune”? Paolo Buonanno, Francesco Drago, Roberto Galbiati, and Giulio Zanella step into these treacherous waters with a new paper (pdf):

Contrary to common perceptions, today both property and violent crimes (with the exception of homicides) are more widespread in Europe than in the US, while the opposite was true thirty years ago. We label this fact as the “reversal of misfortunes”. We investigate what accounts for the reversal by studying the causal impact of demographic changes, incarceration, abortion, unemployment and immigration on crime. For this we use time series data (1970-2008) from seven European countries and the U.S. We find that the demographic structure of the population and the incarceration rate are important determinants of crime. Our results suggest that a tougher incarceration policy may be an effective way to contrast crime in Europe. Our analysis does not provide information on how incarceration policy should be made tougher nor does it provide an answer to the question whether a such a policy would also be efficient from a cost-benefit point of view. We leave this to future research.

I would stress that there are numerous controversial claims in this paper. (I also personally believe that the heavy U.S. reliance on incarceration is morally problematic.) Nonetheless we are committed to bringing you thought-provoking material and so there you go.

For the pointer I thank Noah Smith, who should not be construed as necessarily endorsing any of these results.

More data on survival during maritime disasters

From Mikael Elinder and Oscar Erixson (pdf, final PNAS gated version here):

It’s a widespread notion that women and children are saved first in maritime disasters. The systematic evidence of this comes primarily from the sinking of RMS Titanic. By analyzing individual level data from MS Estonia – one of the largest maritime disaster in the Northern hemisphere since World War II – a different picture emerges. Estonia sunk in the Baltic Sea with 137 survivors and 852 casualties. Despite equal gender rates on Estonia, 111 men, but only 26 women survived. This striking observation, as well as econometric analyses of survival probabilities, shows that the behavior among passengers and crew was clearly inconsistent with the norm that women should be saved before men. We show that the survival patterns from several maritime disasters, including Titanic, can be explained by the behavior of the captain. Women have a survival advantage only when the captain orders that women should be given priority and threatens disobedience with violence. Otherwise women will have lower survival chances.

Assorted links

1. There is no great stagnation markets in everything (cardboard bicycles).

2. Admitting to academic bias.

3. Cyborg America.

4. Where is the one percent cut-off for India?

5. The culture that is Singapore, the accompanying pro-natalist music video is here. The chipmunk remix is here.

Now that’s what I call fiscal policy

If Changsha gets its way, the 100 day battle will just be a start. The city made headlines late last month when it unveiled plans for Rmb829bn ($130bn) in spending on projects ranging from airport expansion to road building, waste treatment and sprucing up the city.

The investment target was jaw-dropping, nearly 150 per cent the size of the city’s GDP last year.

Here is more, Simon Rabinovitch in the FT, “Changsha plan at the heart of China stimulus.” Obviously not all of China will see a comparably large program.

Really uncertain business cycles

There is more to macroeconomics than blogosphere debates often reflect. From Nicholas Bloom, Max Floetotto, Nir Jaimovich, Itay Saporta-Eksten, and Stephen J. Terry (ungated versions here):

We propose uncertainty shocks as a new shock that drives business cycles. First, we demonstrate that microeconomic uncertainty is robustly countercyclical, rising sharply during recessions, particularly during the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Second, we quantify the impact of time-varying uncertainty on the economy in a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model with heterogeneous firms. We find that reasonably calibrated uncertainty shocks can explain drops and rebounds in GDP of around 3%. Moreover, we show that increased uncertainty alters the relative impact of government policies, making them initially less effective and then subsequently more effective.

There is no need to think of this as a competitor to Keynesian or market monetarist theory, rather it is a complement. It suggests that the economy needs “repair of trust” in addition to stronger aggregate demand. It suggests that policy weakness and uncertainty may follow from more general uncertainties, rather than being the primary problem.

This result also addresses some of Evan Soltas’s questions here. As of 2006-2007, it was not commonly understood how volatile the economic environment was, and how broken U.S. finance was. The ongoing problems in the eurozone, even if their effects on U.S. exports are small, are a nagging reminder that “Toto, we don’t live in Kansas any more.”

China estimate of the day

Every 10% cut in US emissions is completely negated by 6 months of China’s emissions growth.

Admittedly, that seems to be calculated at previous growth rates for the Chinese economy, rather than at current or pending rates.

That is from the interesting and provocative Energy for Future Presidents: The Science Behind the Headlines, by Richard A. Muller.

Assorted links

Very good sentences

CSR [corporate social responsibility] with honest moral content, as opposed to anodyne public-relations campaigns about “values”, is a recipe for the politicisation of production and sales.

That is from Will Wilkinson.