Favorite headlines

How should Bernanke speak up about deficits?

…our current fiscal policy has the potential to make it much more difficult for the Fed to carry out its job. Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) recently expressed his enthusiastic support for Bernanke on the expectation that Bernanke would speak out about the need to reduce deficits. Indeed I think Bernanke will do so. But one can speak about the need to reduce deficits (something on which I would like to see both parties come to an agreement) without taking a stand on exactly how that should be done (something on which feathers in the political fight will continue to fly). If Bernanke does speak up on deficits in this limited, bipartisan way, the influence of the Fed Chair’s tongue could grow even greater and the deficit problem might be raised front and center.

That is from EconBrowser. Nouriel Roubini also offers an excellent analysis.

I think Bernanke should tread very carefully. The danger comes if Bernanke signals a problem and nothing good happens in response. That would make it clear that matters will get worse.

True, you cannot fool markets forever. But if we cannot get out of our current fiscal mess, I don’t want markets to learn that all at once. I don’t want markets to learn — again all at once — that our very bright Fed chair is ineffective and that no one in the administration is listening.

Bernanke needs to signal concern about the deficit in exactly the right way. Ex post, he needs plausible deniability about having complained too loudly. Ex ante, he needs to signal he is complaining. (That’s a tough combination, eh?) Too much squawking, too soon, would be a mistake. Instead he should play the chess strategy — "The threat is stronger than the execution" — and over time subtly shift the rhetorical bargaining power in Washington toward fiscal sanity. A "do or die" stance won’t turn out well when the Administration cannot coordinate with an increasingly rebellious Congress, and that is assuming the Administration wants to do something good in response. Finally people who play "showdown" or "chicken" with the Bush Administration don’t, er, always come out so well…

Markets in everything — funeral guests

Liu and her five-member Filial Daughters’ Band are part of a thriving mourning business in Taiwan. They’re professional entertainers paid by grieving families to wail, scream and create the anguished sorrow befitting a proper funeral.

The performances are as much a status symbol for the living as a show of respect for the dead on this island of 23-million people lying 145 km off the Chinese coast.

Weary, grieving relatives hire groups like the Filial Daughters’ Band to perform their mournful stuff for $600 for a half day’s work.

Here is the link, and thanks to Pablo Halkyard for the pointer.

My avian flu policy paper

The piece is about forty pages, here is the pdf link. Your comments are welcome, either below or by email. You already have heard bits and pieces of this: pro-intellectual property, pro-decentralization, and skeptical of quarantine and centralized stockpiles. A good plan also should prove useful for catastrophes other than avian flu. Here is the Executive Summary of the piece:

To combat a possible avian flu pandemic, we should consider the following:

1. The single most important thing we can do for a pandemic–whether

avian flu or not–is to have well-prepared local health care systems. We

should prepare for pandemics in ways that are politically sustainable

and remain useful even if an avian flu pandemic does not occur.2. Prepare social norms and emergency procedures which would limit

or delay the spread of a pandemic. Regular hand washing, and other

beneficial public customs, may save more lives than a Tamiflu stockpile.3. Decentralize our supplies of anti-virals and treat timely distribution as more important than simply creating a stockpile.

4. Institute prizes for effective vaccines and relax liability laws

for vaccine makers. Our government has been discouraging what it should

be encouraging.5. Respect intellectual property by buying the relevant drugs and

vaccines at fair prices. Confiscating property rights would reduce the

incentive for innovation the next time around.6. Make economic preparations to ensure the continuity of food and

power supplies. The relevant “choke points” may include the check

clearing system and the use of mass transit to deliver food supply

workers to their jobs.7. Realize that the federal government will be largely powerless in

the worst stages of a pandemic and make appropriate local plans.8. Encourage the formation of prediction markets in an avian flu

pandemic. This will give us a better idea of the probability of

widespread human-to-human transmission.9. Provide incentives for Asian countries to improve their

surveillance. Tie foreign aid to the receipt of useful information

about the progress of avian flu.10. Reform the World Health Organization and give it greater autonomy from its government funders.

We should not do the following:

1. Tamiflu and vaccine stockpiling have their roles but they should

not form the centerpiece of a plan. In addition to the medical

limitations of these investments, institutional factors will restrict

our ability to allocate these supplies promptly to their proper uses.2. We should not rely on quarantines and mass isolations. Both tend

to be counterproductive and could spread rather than limit a pandemic.3. We should not expect the Army or Armed Forces to be part of a useful response plan.

4. We should not expect to choke off a pandemic in its country of

origin. Once a pandemic has started abroad, we should shut schools and

many public places immediately.5. We should not obsess over avian flu at the expense of other

medical issues. The next pandemic or public health crisis could come

from any number of sources. By focusing on local preparedness and

decentralized responses, this plan is robust to surprise and will also

prove useful for responding to terrorism or natural catastrophes.

Paul Krugman, circa India

Here is yesterday’s column on health care; I am not sure if the The Hindu will be carrying them all on-line. Arnold Kling offers excellent commentary. Thanks to Eswaran for the pointer.

Can we take care of everyone?

Here is one reader (first quoting me) from the comments section of my post on health care:

"I would admit that we cannot take care of everyone and that we face tough trade-offs."

NO. WE. DO. NOT. YES. WE. CAN.

Here is another:

"I would admit that we cannot take care of everyone and that we face tough trade-offs."

Why can’t we? Other industrialized countries do it. We’d have to raise taxes by a nontrivial amount, to be sure, but we certainly could do it if we wanted to. You don’t get points for intellectual honesty by ruling some policy options out of bounds a priori without explaining why.

Every day about 155,000 people die. They die in Europe too. People die from heart attacks and they die from flu. Children drown in buckets and people die in car crashes. We don’t call these health care problems but they still kill you. We could spend the Laffer-health-maximizing percent of our gdp on health care and these people still would die, sooner or later. Most would still die sooner. We could repeal the Bush "tax cuts" and they still would die. The world also has several billion very poor people, and other billions of moderate but not wealthy means. They count too.

We can take some limited group of these people and make them better off by selective health interventions. But we should choose the targets of our benevolence carefully, and we should remain cost effective. No matter how good a job we do, many more people will slip through our fingers. Those who are "taken care of" receive only marginal improvements for temporary periods.

The liberal tendency is to want to feel that you are taking care of everybody. Policies, such as national health insurance, maximize this feeling. In the process the idea of margin is often forgotten.

Philosophical observations: Conservatives, liberals, and libertarians all exhibit different attitudes toward death. Conservatives are obsessed with death; look at their emphasis on abortion, capital punishment, and the need to kill people in our foreign policy. In their view death is everywhere, and we must make hard decisions to limit it (banning abortion and invading other countries, for a start). Liberals promote an ethic of caring, and prefer not to let death enter the political calculus too much. Most of all, they will tell us death is to be avoided. But thinking too closely about death leads us to feel we are not taking care of everybody; furthermore it shows this ethic to be ill-defined or impossible. Libertarians are closer to the liberal attitude, although a liberty ethic replaces a caring ethic. If libertarians thought too much about death, they would have to admit that it is the greatest loss of liberty possible (even worse than taxes), which might lead to government intervention. At the very least it would imply an emphasis on positive rather than negative liberties.

The conservative attitude toward death — at least in general terms — is the most accurate and realistic of the bunch, but also the most dangerous. By rubbing death in our faces, it can inure us to the horrors of killing people or letting them die.

British fact of the day

Percentage of British adults who are members of any of their country’s three major political parties: 1.2

Percentage who are members of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds: 1.9

That is from Harper’s Index, December issue.

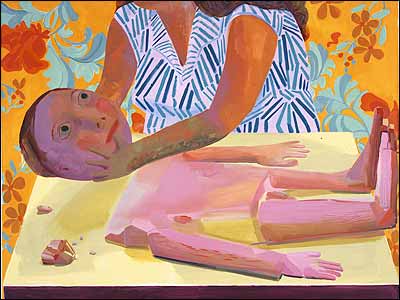

Dana Schutz

Here is the (cute) artist. Here is an article. Try this picture too. Here is Presentation, go see it in MOMA, I am still thinking about it.

What is wrong with American food?

What’s the scoop here? Why is it that even with lots of money and chefs who clearly know how to produce three-star food, American restaurants still can’t measure up to their French counterparts?

The context is the new Michelin guide, and whether four New York restaurants deserved three stars. (BTW, even if you think they were deserving, as I do, count the relative number of stars in NYC vs. Paris; NYC does top San Sebastian, Spain, but not by so much). His commentators make many good points, most of all about differences in ingredient supply networks.

The better pure ingredients in Paris include amazing cheese shops, perfect bread, and fresher strawberries. On the macro scale, this translates into superior haute cuisine.

America, in contrast, excels in multi-dimensionality. Move away from refined Michelin-style cooking, and New York City is usually better than Paris. We have better Indian food, Columbian food, Afghan food, Chinese food, sushi, burger joints, street pretzels, and so on. Yet there is probably no single cuisine where NYC is #1 in the world, precisely because American ingredients are not up to scratch.

It is no accident that France specializes in uni-dimensional food competition, whereas the United States scatters its culinary energies in many directions. By choosing food networks which emphasize speed, reliability, and cheapness over perfection, the U.S. makes possible many more ethnic cuisines, and it also guarantees a better shot at cheap prices. In short, New York offers more choice.

Unlikely film adaptations, part II

Leonardo DiCaprio is to play a man with a particular gift for reading body language in the forthcoming adaptation of Blink, Malcolm Gladwell’s bestseller about how people make snap decisions. The writer-director will be Stephen Gaghan, who won an Oscar for his screenplay of 2000’s drug trade film Traffic. "[Gaghan] came to me out of the blue," Gladwell told trade magazine Variety. ‘He thought there was something in the book that was a movie. We took one chapter from the book and fashioned a story out of it. But most of it is something we dreamt up together."

Thanks to http://kottke.org, now touring Asia, for the pointer. Here is updated information on a previous installment in this series. So who will star in Freakonomics?

Why do parents talk with their childrens’ friends?

As a teenager, some of my friends became quite chummy with my parents. But usually teenage children want their parents to stay quiet. Why might a parent wish to talk to other teenagers?

1. The parent seeks to estimate the quality, or at least the politeness, of the child’s friends.

2. The parent wishes to feel connected to younger generations.

3. The parent is nervous and wishes to relieve the tension of quiet. And not speaking is seen as an abdication of parental responsibility.

4. The parent wishes to establish the authority to do something the child does not like.

5. The parent finds those children genuinely interesting.

6. The parent wishes to pretend a reasonable relationship with the peers of their child, either to feel involved or to pretend that everything will be OK.

None of these motives are popular with the sons and daughters of the conversing parent. If a put on my technocratic Paretian hat, this is sooner an activity to be taxed than subsidized.

Demand curves slope downward

Check out Paul Krugman mentions in the blogosphere.

Addendum: His column today on the Medicare drug bill is excellent, and I otherwise would have linked to it. Here is one partial version.

Second addendum: Gary Karr, Medicare’s chief spokesman, sent me the following in an email:

Tyler Cowen pretends he is a Democrat

If I were a Democrat…

First, I would not cite evidence about how Western European countries spend less on health and are healthier than U.S. citizens. This data set, if you take it seriously, also implies that the marginal product of more health care, adjusting for income and a few other variables, is zero. Expanding health care would not be important. Now I believe this is an incorrect conclusion, but that is what shows up in this data. We should not invoke this data selectively.

Second, I would recognize that American policy generally works (or doesn’t work) by building upon existing institutions. The most likely form of national health care — for better or worse — would extend a version of Medicare to more people. This would not lower health care costs, whether in gross or quality-adjusted terms. Keep in mind that negotiating price reductions does not per se lower real resource costs at all.

I would disaggregate health care systems and see where we could do the most good:

1. Step up R&D subsidies through the NIH and our university system, both high quality institutions. Their autonomy and micro-fiefdoms provide a good framework for risk-taking and innovation. The returns to medical R&D are extremely high. Furthermore the case for market failure, based on the inability to capture the full social gains from a new idea, is simple.

2. Redo the Medicare drug bill so that people can understand it (even I can’t, nor does my mother), and so more people benefit. If need be, we can do this in budget-neutral fashion. The Bush plan is a mess.

3. Invest in local public health systems. Preventive care is important, especially for the poor. Price can be an obstacle but often the relevant constraints are behavioral in nature. Public health care systems should be easy and inviting, and they have to become part of life routines. Government can be part of the solution. Strong local public health care also will improve surveillance and later surge capacity if a pandemic comes along; this added benefit is significant.

4. Borrow a page from the libertarian litany about the FDA.

5. Institute prizes for successful vaccines. We have been discouraging vaccine production when we should be encouraging it; Michael Kremer has some intriguing proposals.

All those options are doable. All would save lives. None are fiscal disasters. They offer something for both rich and poor. They lay out a positive and constructive role for government, while keeping room for the private sector. None raise the prospect of excess bureaucracy or discourage innovation. None rest on the questionable belief that government as single supplier or payer would improve efficiency. And they are all areas where the Republicans are dropping the ball.

I would cut talk of national health insurance. I would cease obsessing over the number of "40 million uninsured," however good a debating point it may be. Many of these people are either linked to immigration or get decent medical coverage in any case. I would admit that we cannot take care of everyone and that we face tough trade-offs.

Hmmm…these counterfactuals are fun. What should I try next? Pretending I am a Republican? But for now, it is back to normal life…and so we return to your regularly scheduled programming. But comments are open, in case Kevin Drum’s readers wish to pretend they are libertarians…

Do cellphones have a role in education?

As a recording device, or for taking down illustrations or graphs, the multifunction mobile phone rivals, or will soon rival, the iPod. Few seem to have noticed, but a whole generation of students have taught themselves shorthand (texting, that is). This has not been exploited educationally.

Ringtone interruptions in a teaching or learning situation are, of course, intolerable. And having to overhear one-sided mobile chatter is as blood-boilingly irritating in the library or computer cluster as it is in the railway carriage. But texting enables rapid notetaking to oneself, silent interchange between auditors at a lecture, or participants in a seminar. Used conscientiously, even today’s generation of phones could be used for teaching purposes – to foster uninterruptive cross-interaction, rapid access to outside information sources, or simple queries ("what the hell did he just say, I missed it?")

I’d be a lot more confident about our universities’ ability to absorb the Gates tablet if, in the lecture hall, the signs on the wall said: "Please turn your mobile phones on".

My predictions: Using cell phones to record lectures is easy, and the playback should speed up the pace. Might the linked information technology improve the lecture by adding material or explanation? How about phones which flash red whenever the instructor says something questionable or controversial? How about phones which monitor the reaction of the individual listener and send this message to the other listeners? So if everyone else is sleeping, upset, or sexually excited, you would know about it. Overall, I do not expect the balance of power to shift in favor of the lecturer.

Here is the source link, and thanks to you-know-who for the pointer. Comments are open if you wish to offer your own predictions.

Kevin Drum leaves out the words “single payer”

Read him here. Canada, North Korea, and Cuba have single-payer governmental systems. If you know of others (I believe there are some), please leave them in the comments. The successes, or supposed successes, of most West European systems do not constitute evidence that a single payer system is a good idea. This is one of the most commonly overlooked points in the debate over health care.