Category: Data Source

Interesting fact about sector weightings

Jason Ruspini writes to me:

Financials peaked as a

percentage of s&p 500 market cap in 2006 at 22%. In 1950, tobacco,

breweries and distillers accounted for 22% of UK market cap.

I am told that is from p.23 of Triumph of the Optimists.

Modern Principles: Macroeconomics, Economic Growth

course an embarrassment. In much of the developing world, diarrhea

is a killer, especially of children. Every year 1.8 million

children die from diarrhea. Ending the premature deaths of these

children does not require any scientific breakthroughs, nor does it

require new drugs or fancy medical devices. Preventing these deaths requires

only one thing: economic growth.

That’s the opening paragraph of The Wealth of Nations and Economic Growth, Chapter 6 in Modern Principles: Macroeconomics. Does the opening make you a little bit squeamish? We hope so–we wanted an opening that would jar students out of complacency and remind them how vital economic growth is to human life. Â

Due to its importance, we have more material on growth and development than any other principles text.  In Chapter 6 we lay out the key facts and the basic framework for understanding economic growth. I think we do an especially good job explaining that the proximate causes of growth, increases in capital, labor, and technology must themselves be explained. Why do people save? Why do people invest?  Why do people research and develop new ideas?  It’s these questions which connect macroeconomics to microeconomics and point to the fundamental importance of incentives and institutions. These questions also foreshadow future chapters on savings, investment, financial intermediation and the economics of ideas.Â

For a limited time, you can read Chapter 6 at the link above (and do enjoy the pretty color pictures before you print!).  Tyler and I will be writing more about Modern Principles: Macroeconomics this week; you can also find more information at www.SeeTheInvisibleHand.com.

Coming soon

There is a Micro book and a consolidated text as well. Please do contact Alex or me if you are interested in classroom use.

Addendum: Arnold Kling comments.

Laissez-Faire, eh?

U.S. government spending as a percentage of GDP is now equal to Canada's and rising, leading one Canadian op-ed writer to crow about Canada's low tax, free market economy. Damn that hurts.

Google Data

Google has tied BLS data to a nifty graph utility making it very easy to examine say unemployment rates across counties, states and so forth. Do a search for unemployment rate, click on the top graph and check it out. More is planned.

Hat tip to Flowing Data.

Debating Economics

Intelligence Squared has held a series of debates in which they poll ayes and nayes before and after. How should we expect opinion to change with such debates? Let’s assume that the debate teams are evenly matched on average (since any debate resolution can be written in either the affirmative or negative this seems a weak assumption). If so, then we ought to expect a random walk; that is, sometimes the aye team will be stronger and support for their position will grow (aye after – aye before will increase) and sometimes the nay team will be stronger and support for their position will grow. On average, however, we ought to expect that if it’s 30% aye and 70% nay going in then it ought to be 30% aye and 70% nay going out, again, on average. Another way of saying this is that new information, by definition, should not swing your view systematically one way or the other.

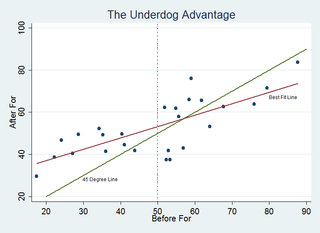

Alas, the data refute this position. The graph shown below (click to enlarge) looks at the percentage of ayes and nayes among the decided  before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

I see two plausible possibilities.

1) If the side with the larger numbers has weaker adherents they could be more likely to change their mind.

2) The undecided are key and the undecided are lying.

For case 1, imagine that 10% of each group changes their minds; since 10% of a larger number is more switchers this could generate the data. The problem with 1 and with the data more generally is that we don’t seem to see a tendency towards 50:50 in the world. We focus on disputes, of course, but more often we reach some consensus (the moon is not made of blue cheese, voodoo doesn’t work and so forth).

Thus 2 is my best guess. Note first that the number of “undecided” swing massively in these debates and in every case the number of undecided goes down a lot, itself peculiar if people are rational Bayesians. A big swing in undecided votes is quite odd for two additional reasons. First, when Justice Roberts said he’d never really thought about the constitutionality of abortion people were incredulous. Similarly, could 30% of the audience (in a debate in which Tyler recently participated (pdf)) be truly undecided about whether “it is wrong to pay for sex”? Second, and even more doubtful, could it be that 30% of the people at the debate were undecided–thus had not heard arguments in let’s say the previous 10 years that converted them one way or the other–but on that very night a majority of the undecided were at last pushed into the decided camp? I think not, thus I think lying best explains the data.

Some questions for readers. Can you think of another hypothesis to explain the data? Can you think of a way of testing competing hypotheses? And does anyone know of a larger database of debate decisions with ayes, nayes and undecided before and after?

Hat tip to Robin for suggesting that there might be a tendency to 50:50, Bryan and Tyler for discussion and Robin for collecting the data.

False Economy, by Alan Beattie

I enjoyed the book, most of all the chapter comparing Argentina and the United States. I was struck by this bit:

New York is the only one out of the sixteen largest cities in the northeastern or midwestern states whose population is larger than it was fifty years ago.

Over that same time period our national population has roughly doubled. The subtitle of the book is A Surprising Economic History of the World.

Assorted Links

- Hayek v. Keynes in elegant powerpoints developed by Roger Garrison. Hat tip to Taking Hayek Seriously.

- The Independent Review (I am an assistant editor) appears in several scenes in the new Crowe, Affleck movie, State of Play. David Theroux says the movie would have been better had the writers paid more attention to the contents.

Location, location, location

Craig Newmark reports:

Matthew Kahn notes that one median-priced house in Westwood could be exchanged–ignoring transactions costs–for 100 median-priced houses in Detroit. Would this be a good trade? I report, you decide.

If you are skeptical, here are the data on Detroit.

Which are the most neurotic states?

There is much more here on the geographic distribution of other major personality traits. The high conscientious people seem to cluster in the Plains. Openness is strong in the Pacific West, New England, Texas, and Florida. The upper Midwest dominates for extroversion.

I thank Ian Plosker for the pointer. The underlying research is here.

He forgot about Hawtrey

Ezra reports, from his commentator Nylund:

Is it just me or do famous economists seem to live a really long time?

Friedman (94)

Mises (92)

John Kenneth Galbraith (98)

Hayek (92)

Leontief (93)

…besides Keynes (or any of the really old school guys like

Ricardo and Say), its rare to find a major economist that didn't make

it well into their 80's.

Samuelson is in his 90s and Ken Arrow is 87. Buchanan, Tullock, Coase, and Vernon Smith are all still with us and I wonder if Gary Becker might prove immortal. Frank Ramsey is one obvious exception, as is Miguel Sidrauski. Fischer Black and Amos Tversky are two more recent exceptions. Here is a paper on 16 notable economists who died prematurely.

Which new mothers are most likely to abandon their old jobs?

Jane Leber Herr tells us:

Looking at these women 15 years after graduation, when they are approximately 37 years old, we find the same pattern seen elsewhere; among mothers with a graduate degree, MDs are the most likely to be working (94%), and MBAs are the least likely (72%)…Among PhDs, 86% are working, among lawyers (JDs), 79%, among women with non-MBA masters, 74%, and among those with no graduate degree, 69%.

These basic differences across professions seem to hold up once other measurable factors are controlled for. Most of the short essay focuses on causality; the family-friendliness of the job environment may be one important factor.

Data revisions

Simon Johnson notes:

We don’t know how much of banking profits in recent years were illusory

and should not have been booked as GDP. In fact, it would not be a big

surprise if – eventually – we go back and mark down our true production

of goods and services in 2007 by 2 or even 5 percent. In this sense,

we face a statistical situation similar to that of the Soviet Union at

its demise – once they figured out that all their military production

had no real value, they had to reduce measured GDP sharply.

Don't forget to make another adjustment for the real value of health care and whether it rose proportionately with expenditure.

Comparing Recessions 4

GDP was down at a 6.2% annualized rate in the last quarter of 2008 (revised figure). Earlier I criticized the Minneapolis Fed for a peculiar way of presenting data comparing recessions. I've been impressed, however, with how they have responded since I (and others) raised this issue. First, they quickly clarified what they were doing. Second, today they have added a very nice javascript which lets you compare output and employment during this recession to as many others as you like with a few clicks. Check it out.

Do conservative magazines take liberty seriously?

Daniel Klein and Jason Briggeman say maybe not:

Abstract:

Conservatives say they are for small government and individual liberty,

but a

content analysis of leading conservative magazines shows that most have

preponderantly failed to take pro-liberty positions on sex, gambling,

and

drugs. Besides many anti-liberty commissions, the magazines may be

criticized

for anti-liberty omission–that is, failing to oppose anti-liberty

policies.

Magazines investigated include National

Review, The Weekly Standard, The

American Enterprise,

and

The American Spectator. We find that National

Review has had the strongest

record on liberty on the issues treated, while the others have

preponderantly

failed to be pro-liberty or have even been anti-liberty.